Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

Chef Ana Sortun Is Working Hard To Keep Her Acclaimed Restaurants Afloat

This week Ana Sortun, the culinary force behind the Cambridge restaurant Oleana, earned a coveted James Beard Foundation award nomination for Outstanding Chef. Her partnering chefs Cassie Piuma at Sarma in Somerville and baker Maura Kilpatrick at Cambridge's Sofra were also recognized with what have been called “the Oscars of the food world.”

But the prestigious accolades come at a time when unprecedented, damaging disruption is ripping through the nation's food service industry. Like more than 90% of Massachusetts restaurant owners, Sortun and her business partners have been forced to furlough most of their staff at their three wildly popular spots because of the coronavirus closures. Now the executive chef and her 150 employees are navigating rough, unchartered waters to stay afloat.

When I spoke with Amber Gouveia she flashed back to applying for a job with Sortun last summer. Then she went back farther, conjuring memories of the life-changing meal she had at the pioneering chef's 20-year-old restaurant.

“The first time I went to Oleana I was still in culinary school,” Gouveia recalled, “it was opening my mind to 'this is what good food is.'”

The dishes were creative, bold and unpretentious. “It was all interesting things I'd never seen before, techniques I've never used before,” Gouveia said.

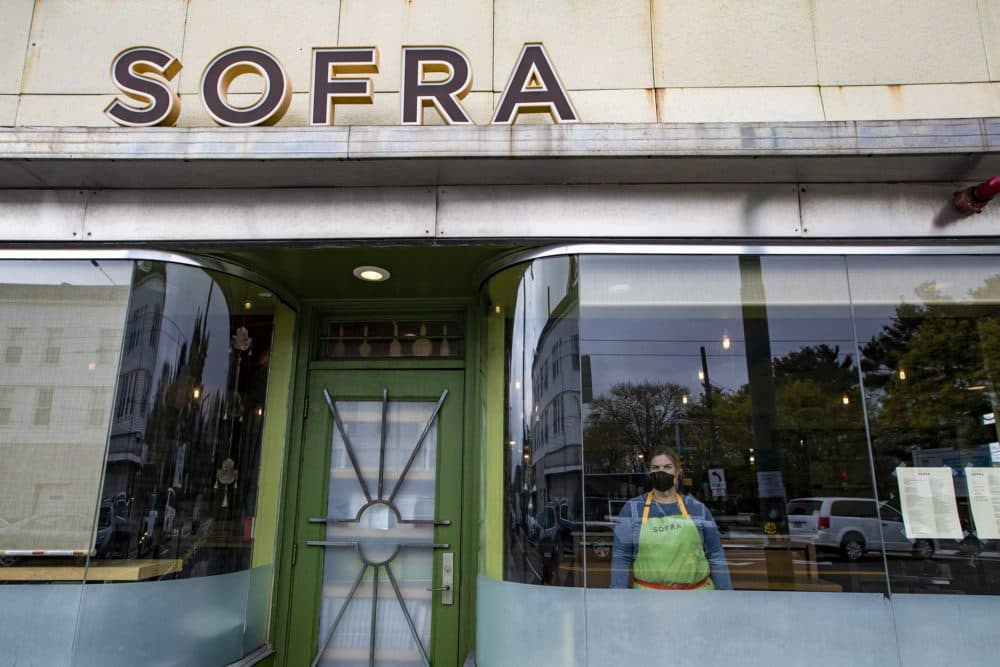

She was thrilled to win the sous chef position at Sofra Bakery and Cafe, the second in Sortun's steady evolution that opened in 2008. As a new employee Gouveia embraced learning how to craft savory, Middle Eastern-inspired cuisine while navigating the kitchen's tight quarters and rolling with the punches. Pre-coronavirus she said Sofra was a busy “beast” every day.

“Before all of this happened, especially on the weekends, there were lines out the door from 8:30 in the morning until 4:00 in the afternoon,” Gouveia recalled, “which is amazing.”

Imagine being a chef at not one, not two, but three jamming restaurants in Boston's competitive food scene...and then it just stops.

“Yeah. It's a really, really strange feeling,” Sortun shared, “for sure.”

Since shutting down in mid-March the chef, cookbook author and entrepreneur has been worrying about the fate of her three businesses and her 150 employees. A handful are working the new curbside takeout service at Sofra that she and her partners launched a few weeks ago to help keep the restaurants alive.

Advertisement

They did not make the decision lightly. Adjusting to the new world food order required new strategies, new systems, re-thinking menus and, above all, safety protocols for customers and the skeleton crew on deck. Sortun said at Sofra the teammates that rely so heavily on their senses don't feel like themselves.

“Cooking with a mask is new,” she said, “None of us have ever cooked without being able to smell anything.”

Staying at a distance in Sofra's tiny kitchen is also challenging, Sortun explained. Two full-time bakers, four cooks and herself are doing staggered shifts. A pair of managers are handling logistics for orders being fired at scheduled pick-up times. Now customers wait outside, six feet apart, instead of crowding into the colorful, cozy space that's lined with shelves of aromatic spices

Sortun feels responsible for her entire staff's physical, emotional and financial health after witnessing everything they've built crumble beneath them. She said each one of them is experiencing it differently.

“It's just such as a cross section of life, the whole industry, right?” Sortun said, “There's a lot of professionals in our restaurant – a lot of professionals – people that, you know, this is what they're gonna do forever.”

Now that Sofra catering manager Macy Radloff has been furloughed she wonders when her role will be necessary again.

“My whole identity has been tied up in this job for the last six years,” she told me, then asked, “what do I do now?”

Radloff said she used to work 45 to 60 hours a week orchestrating lunches, dinners and events for clients including Harvard and M.I.T. She misses the work, and her colleagues, but feels lucky to be getting unemployment in addition to $600 a week from the CARES Act fund. Not all of her co-workers are eligible for government assistance and Radloff said right now some need to work more than she does.

Pastry chef Feyza Bayrakcioglu-Özden is relieved to be back at Sofra. She's from Turkey, and speaking from the kitchen she explained how concerned and stressed she's been because of her status.

“I'm here with a work visa, if I'm not working maybe I have to leave,” she said, “So that was the biggest issue for me.”

Bayrakcioglu-Özden is able to stay in the U.S. on an O-1 Visa for her expertise in Turkish cuisine. She's consulted with attorneys about the unclear visa situation and is thankful to be preparing sweets for takeout.

Line cook Jean Solon is handling a few shifts too.

“I mean we're all in the same boat,” he said of the situation, “we're just waiting to see what will happen.”

He lives in hard-hit Chelsea and said his wife is incredibly scared of the virus. Solon feels good about contributing during the pandemic and shared his unique perspective.

“I'm from Haiti,” he said, “we're used to suffering. Imagine if you're from a third world country, so that's not going to crush you down that bad.”

Solon's a restaurant industry veteran with 20 years under his belt at Sortun's restaurants. He's worked both in the front and back of the house.

“In this country, and all around the world, half of the people are going to lose their job anyway because we can't really do what we used to do before,” he said, “Ten people used to be in a kitchen – now it's going to be five – so what's going to happen to the other five? Who knows, maybe in a year or two we'll see what happens, but it's not gonna be easy.”

While Solon is happy to be getting out of the house, sous chef Amber Goveia opted not to work at Sofra right now for fear of being exposed to the virus.

“I'm a person with asthma,” she said, “a pre-existing condition that definitely gave me pause.”

Goveia added she also couldn't risk exposing her 59-year-old father who's pre-diabetic and has bronchitis. She cooks for him regularly and helps clean his house. It took a few weeks for Goveia's unemployment to come through and she said the CARES money is helping.

“Without that I feel like it would be a much different ballgame,” she said, “I'd feel like I would have a little lump in my throat all day.”

Without having to go to work it can be hard for Goveia to get up in the morning. She plans to return to Sofra once the state's closure orders are lifted and the outbreak feels more controlled. “I would never leave my team behind,” she said.

Working for a restaurant is like being part of a family, Jenna Lyons explained. The furloughed marketing and events director for Oleana and Sofra misses being part of the unit and fought back tears thinking about her disappointed clients. Before the crisis hit she was planning a slew of weddings and birthday parties.

“That's been a big heartbreaker for everyone,” Lyons said. “It's really hard to have to talk to people that you've gotten really close with to tell them that you're not sure what's going to happen with their event.”

Lyons had a difficult time signing up for unemployment because of a glitch in the online enrollment system. After three weeks of trying every day she found herself getting uncharacteristically mad and frustrated. Her bosses were concerned about what was going wrong.

After making countless calls and attending 18 unemployment town halls she ultimately ran with advice to email state representatives along with the governor's office. After seven weeks of fretting and scrambling it worked.

“So now I have been paid for just two weeks,” she said, “But I'm in the system so I feel good.”

Nothing is easy these days for Sortun. The takeout service isn't paying the rent, she said. That and payroll are the restaurants' biggest expenses. Sortun and her partners finally got approval for low-interest loans through the Payroll Protection Plan. But, like thousands of other small business owners, they're not sure the borrowed money will be forgiven.

Looking ahead, Sortun said packing boxes for pick-up isn't going to be temporary – it's going to be 2020.

“If we are allowed to reopen again we're going to only be able to have a few people standing in the building at the same time. We've got to get used to wearing masks,” she said. “None of it sounds good, right?”

Some days Sortun said she just wants to rant about it all being too much. On others the chef feels gratitude for having a sense of purpose and for still being able to go into her kitchen to thoughtfully prepare food for others.

“I can't imagine doing anything else,” Sortun said. “I don't know how to do anything else.”

This segment aired on May 8, 2020.