Advertisement

Fact Checking Kennedy And Markey On Their Black Lives Matter Claims

Resume

Massachusetts voters were the first to elect a Black person to the U.S. Senate, in 1966. But in 2020, amid a national reckoning on racism, they almost certainly will reelect Sen. Ed Markey, a white man who has spent more than four decades in Congress, or replace him with Rep. Joe Kennedy, a white man who would be the fourth member of his family to become a senator.

The incongruity of the current moment and this Democratic primary matchup crystallized during a debate this week.

"Let's just get real for a moment," moderator Latoyia Edwards of NBC Boston said. "There are Black and brown people watching right now, Black mothers like me who are looking and saying, 'In this time of social justice, representation — optics — matter.' ... They see two white men vying for the U.S. Senate seat to represent Massachusetts."

Edwards pressed the candidates to "give us specifics on what you've done, and what you will do, to show that Black lives matter."

Markey and Kennedy took similar approaches to what may be a key question in their contest, each beginning with an anecdote meant to demonstrate early allyship that was principled, not popular. But closer examinations of the episodes Markey and Kennedy recounted suggest they may not have been quite as bold as they would have voters believe.

'One Of The First Democrats To Declare That Black Lives Matter'

In Kennedy's telling, he used one of the biggest opportunities of his political career to take a stand that others in his party shied away from.

"When I was asked to give the Democratic response to Donald Trump's first State of the Union — with that national platform — I was one of the first Democrats to declare that Black lives matter," Kennedy claimed.

In reality, Kennedy didn't make his own declaration that Black lives matter on that night in January 2018; rather, he quoted demonstrators who use "Black lives matter" as a rallying cry.

Kennedy included the demonstrators, along with police officers, in a section of his speech that lauded various people for actions he considered admirable. Here's an excerpt, with emphasis added:

You swarmed Washington last year to ensure no parent has to worry if they can afford to save their child's life.

You proudly marched together last weekend — thousands deep — in the streets of Las Vegas and Philadelphia and Nashville.

You sat high atop your mom's shoulders and held a sign that read: "Build a wall, and my generation will tear it down."

You bravely say, "Me too." You steadfastly say, "Black lives matter."

You wade through flood waters, battle hurricanes, and brave wildfires and mudslides to save a stranger.

You fight your own, quiet battles every single day.

You drag your weary bodies to that extra shift so your families won't feel the sting of scarcity.

You leave loved ones at home to defend our country overseas, or patrol our neighborhoods overnight.

Kennedy's remarks signaled support for the Black Lives Matter movement, but there is a meaningful difference between actually "declar[ing] that Black lives matter" and merely attributing the phrase to others — even approvingly — said Daunasia Yancey, the founder of Black Lives Matter Boston.

"We need more," Yancey said. White allies such as Kennedy and Markey may have done "more than what everyone else did" in the past, she added, but in her view that is "because mostly what everyone else did was nothing."

"The back-and-forth trying to get a medal for caring is silly, and it's not useful," Yancey said.

In a statement, Kennedy spokesman Brian Phillips Jr. said, "Joe was proud to use one of the Democratic Party's highest platforms to recognize the BLM movement and the activists driving change in every corner of the country."

As for timing, Kennedy's claim to have been "one of the first Democrats" is hard to evaluate because it is imprecise. It is certainly true that many politicians were slow to adopt the phrase "Black lives matter" until it was mainstream enough to be emblazoned inside and outside Fenway Park.

It is also true that, as Chicago Tribune columnist Dahleen Glanton wrote in 2016, "The second day of Hillary Clinton's Democratic National Convention could have been subtitled 'Black Lives Matter.' "

Glanton continued:

[Clinton] made it clear where she stands on the controversial issue when she invited nine mothers who have lost children at the hands of police or by street violence to speak on her behalf.

The mothers of Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner and others collectively made perhaps the most impassioned plea yet on Tuesday for rallying around Clinton's presidential bid: She isn't afraid to say that black lives matter ...

Their remarks brought many of the delegates to tears. Chants of "Black Lives Matter" swelled from the convention floor.

Clinton's top competitors in the 2016 Democratic presidential primary, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and former Maryland Gov. Martin O'Malley, also said "Black lives matter" during the campaign. Then-President Barack Obama repeatedly defended the phrase against critics who said it diminished other lives.

And Markey used it at a Martin Luther King Jr. Day event that year.

So, while Kennedy was ahead of some in 2018, he also was in the company of some of his party's most prominent members.

'It Hurt My Career'

Asked during Sunday's debate what he has done "to show that Black lives matter," Markey started by citing his support for creating a majority-Black state Senate district in 1973. He was a freshman in the state House of Representatives, at the time.

"I had to make a decision to take on the Democratic state leadership to make sure there was a Black Senate seat, and I did," Markey said. "And it hurt my career."

Any price Markey may have paid for his stance would appear to be modest, however. He won reelection the following year and styled himself as a political maverick when he ran successfully for Congress in 1976.

"In the end, it didn't hurt his career," Markey Campaign Manager John Walsh allowed, "because he didn't last there very long. He moved" on to Washington.

Though things worked out, Markey did assume some political risk. Redrawing the 40-seat state Senate map to create a majority-Black district meant that an existing member of the chamber would likely lose his place — and jeopardizing a fellow lawmaker's reelection chances is no way to make friends.

In an interview, Markey said he acquired a "pariah-like status," though he acknowledged that was not because of his support for a majority-Black district alone. Bucking party leaders became "the pathway that I walked, and the first vote on that pathway was the Black Senate seat."

The most significant vote was not related to racial justice but rather to judicial reform, Markey said. In that standoff, he so aggravated some fellow Democrats that they stuck his desk in a State House hallway, in a show of protest.

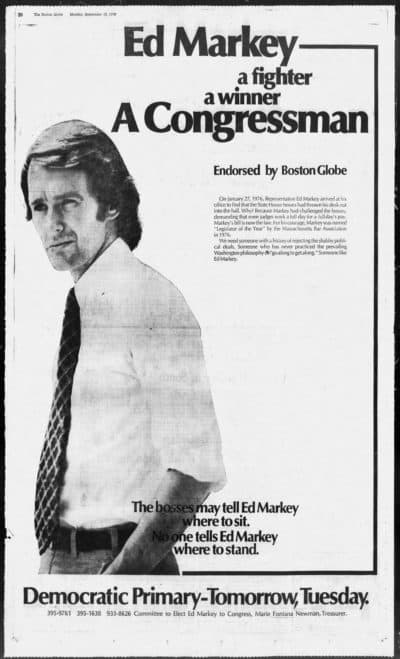

Markey spun the incident into a campaign slogan: "The bosses may tell Ed Markey where to sit. No one tells Ed Markey where to stand."

Bill Owens, who became the first Black state senator in Massachusetts, has endorsed Markey for reelection to the U.S. Senate this year. In a campaign video, Owens vouches for the notion that Markey stuck out his neck during the debate over a majority-Black district 47 years ago.

According to Owens, senior Democrats in the state Legislature "began to threaten [Markey] that he would lose his seat and that he would not be able to be elected ever again in Massachusetts."

Those threats proved hollow and, though Markey could not have been certain of their emptiness at the time, his "decision to take on the Democratic state leadership" may have been eased by powerful allies.

Then-Gov. Francis Sargent was a vocal supporter of creating a majority-Black state Senate district. He vetoed a redistricting proposal because it failed to create one, saying, "I will not approve a plan that, in effect, disenfranchises a large number of the commonwealth's citizens."

The push for a majority-Black district also had the influential backing of Massachusetts' senior U.S. senator at the time: Ted Kennedy.

And while Owens credits Markey for supporting a majority-Black district, he said in an interview that "the guy who was the leading member of the white community that we relied on was Barney Frank," a state representative at the time, before his 32-year tenure in Congress.

Frank accused the state Senate president of squashing bills in retaliation against lawmakers who advocated for a majority-Black district. But Owens said he "could not imagine" that Markey was targeted.

So, although Markey strained relations with some important colleagues in the state Legislature, he also had political heavyweights on his side and ultimately parlayed his "troublemaker" reputation, as Walsh described it, into higher office.

'I Will Always Give People Credit Who Stand For The Right Thing'

Whether Markey and Kennedy merit profiles in courage, "I will always give people credit who stand for the right thing, regardless of what the description is," said Setti Warren, executive director of Harvard's Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy.

"I don't doubt either Congressman Kennedy's or Senator Markey's commitment to seeing progress being made for Black people in our state and our country," he added.

Markey has cosponsored a reparations bill filed by Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey and is partnering with Rep. Ayanna Pressley of Boston on legislation that would end qualified immunity for police, the legal doctrine that shields public officials from personal liability for acts committed in the line of duty.

Kennedy is a founding member of the Black Maternal Health Caucus and is partnering with Rep. Hakeem Jeffries of New York on a bill that would facilitate prosecutions of police officers for civil rights violations.

Still, Warren echoed Yancey's call for figures such as Markey and Kennedy to do more, saying "the policies and the efforts that have been promoted by many politicians have not worked."