Advertisement

Sonya Clark Unravels American Propaganda In 'Monumental Cloth'

The Confederate flag or the “rebel flag” is an image that many of us have seen at some point in our lifetime.

It’s plastered on T-shirts, cups, keychains and bumper stickers. It blows in the wind from the steeples of barns, houses and businesses. It’s even been immortalized through television shows like “The Dukes of Hazzard” and films like “The Birth of a Nation.” It’s the flag that almost everyone knows. At the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, artist Sonya Clark challenges us to see past what we think we “know” in her exhibit “Monumental Cloth, The Flag We Should Know.”

Thirty feet long and 15 feet wide, “Monumental Cloth” is a massive recreation of a flag that history seems to have forgotten. When Gen. Robert E. Lee and his troops surrendered to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in 1865, a simple white, waffle weave dishcloth with red stripes was exchanged. Known as the flag of truce, that little cloth represented the end of the Civil War and the beginning of Reconstruction, a new era of American history. “When I first encountered the truce flag, I realized I’d never seen the symbol before,” Clark says. “It’s not something that’s in our everyday mind like the Confederate Battle Flag is.”

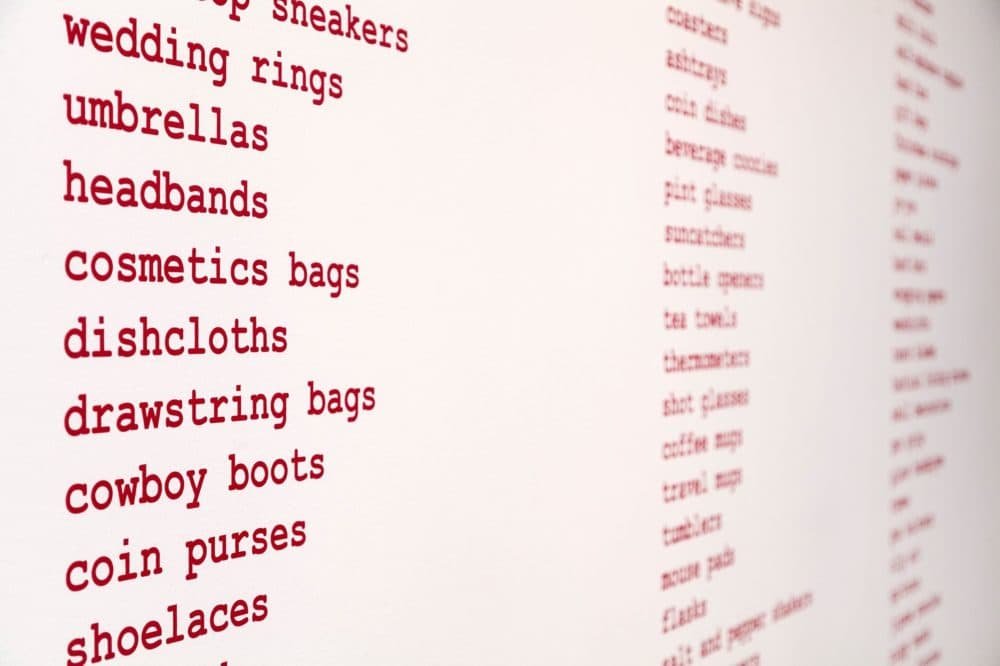

A long list of different items emblazoned with the Confederate flag march down a wall in “Monumental Cloth.” From yoga mats to tube tops to washcloths, the Confederate flag is a symbol that permeates our visual culture, even outside of the United States. “I’ve seen the Confederate flag in Canada,” says Clark. “I’ve seen it in Brazil, in Italy. It’s a symbol that transcends borders because of what it represents.”

There are some who still argue that the Confederate flag is a symbol of Southern virtue, gentility and independence. But the South couldn’t exist without cotton and cotton couldn’t exist without slave labor. When rebel troops began using the flag as a symbol for their resistance, it also symbolized the white supremacist systems needed to allow the South to endure. The flag became more than just a flag, it was “propaganda,” says Clark. “For propaganda to work, you have to sell the people something. And that something was the illusion of Southern gentility and Southern pride.”

The Confederacy and its flag have been revived again and again, notably in 1915 when “The Birth of a Nation” hit theaters, and in 1948 when the flag was used by the States' Rights Democratic Party, also called Dixiecrats. In 2020, then-President Donald Trump declined to denounce the flag, stating that it “represents the South.” The flag also made prominent appearances in January when rioters and Trump supporters stormed the nation’s capital.

This underscores a point that Clark wants to make clear. “I do not want to demonize the South,” she points out. “This isn’t a 'Southern' issue. Human trafficking, slavery and white supremacy are global issues. To localize it to the South is a denial of all those who partook.” Instead, Clark wants those who see “Monumental Cloth” to excavate how propaganda of all kinds becomes a part of our culture and why.

Along with the colossal version of the truce flag, there are smaller, true-to-size replicas titled “Many,” made from historically accurate dyes and materials. Wooden looms also sit in the middle of the exhibit and visitors are encouraged to weave portions of smaller flags as a part of a “reconstruction exercise.” Through this exercise, viewers are not only able to directly contribute to a growing scroll of an elongated truce flag but they’re also able to gain a cursory understanding of the complexity and work that goes into crafting textiles. “One way of knowing something is making it,” says Clark.

Most people probably wouldn’t look twice at the complex waffle-weave pattern that makes up the truce flag. It’s a dish towel, an everyday domestic object. But that’s exactly the point that Clark is making. “It’s the complexity of handmade things. People value cloth in one sense but also take it for granted.”

And often, the hands and the people behind the making of these types of items are also taken for granted. Clark ruminated on the hands that painstakingly picked the cotton and wove the original truce flag. “At the end of the Civil War, suddenly the [slave] labor wasn't free,” she says. “And the technical skills that were embodied in that human being and that might have been passed down from generation to generation, the intelligence of that embodied knowledge was no longer free as well.”

While “Monumental Cloth” certainly unravels a lesser-known portion of American history, it says just as much, if not more, about our present. While slavery may have been legally abolished, it continued on in the form of racist Jim Crow laws, exploitative wages, the prison industrial complex and human trafficking. These things are still happening today. “In American history, there was an opportunity for there to be a turning point after the Civil War, during Reconstruction,” says Clark. “But what actually held on — what endured — was what was surrendered, or the Confederate battle flag. And I think that says a lot about where we are currently.”

In this way, the truce flag is an ambiguous symbol. It does not necessarily represent freedom but what it does portray is the period of uncertainty after cataclysmic upheaval and change. It represents unrealized potential and unfulfilled promises.

But in this uncertainty, there is still hope. To weave a collective fabric that can hold all of us, not just some of us. Through “Monumental Cloth,” Clark hopes to spark these conversations about change. “What happens when we collapse the hierarchy, when we collapse those binaries or at least investigate them?” she asks. “That’s where we need to begin.”

Sonya Clark's "Monumental Cloth: The Flag We Should Know" is on view at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum through Sept. 12.