Advertisement

Commentary

Semi-Documentary 'Wild Style' Is An Essential Look At The Subculture Of 1980s Hip-Hop

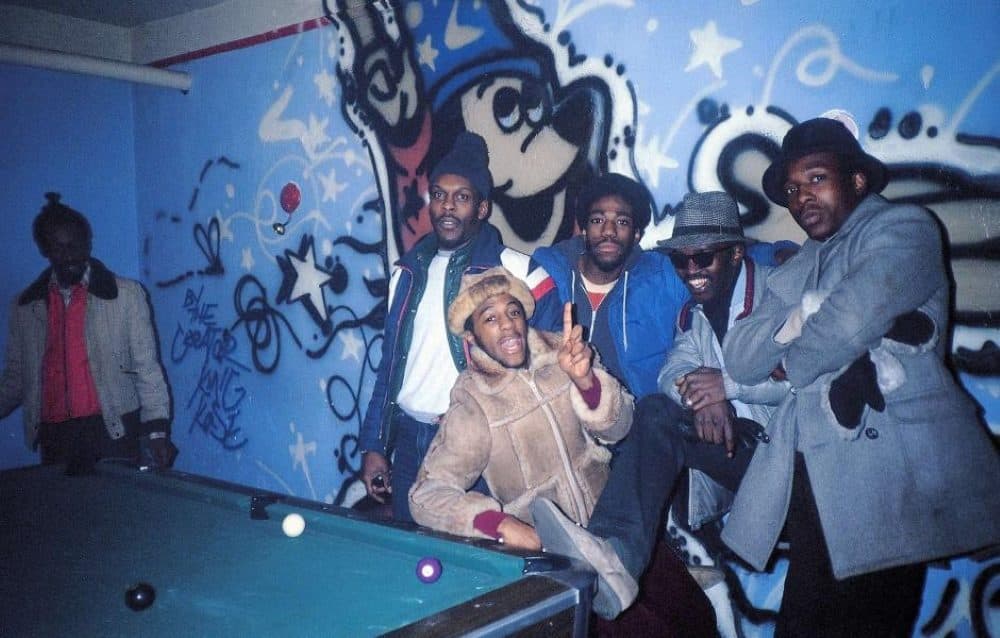

There’s gonna be a heck of a lawn party on Huntington Avenue this Sunday night, as the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston celebrates the closing weekend of their marvelous “Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation” exhibit with a free outdoor screening of “Wild Style.” Director Charlie Ahearn’s seminal 1982 semi-documentary about an aspiring young graffiti artist and the breakers and b-boys he runs with is widely acknowledged as the first (and best) hip-hop movie ever made, though they weren’t even calling it “hip-hop” yet back then. Shot on a shoestring in the South Bronx and on the Lower East Side, it’s an essential, ebullient look at a subculture about to explode into the mainstream. Ahearn and his artistic collaborator/partner-in-crime Fab 5 Freddy will be in attendance at the screening. You should be, too.

Over the years, there have been plenty of more polished, professionally made movies about the music and art that migrated from uptown murals and MTA train yards to the clubs and galleries of Lower Manhattan, spawning a new form of expression that eventually took over the world. But few films are blessed with the sense of discovery captured in these ramshackle reels. “Wild Style” is a fanciful first draft of a cultural history play-acted by the same people who created the culture in the first place. It’s a winning bit of self-mythology by folks who were there on the ground floor, adorable in it’s amateurish ardor and endless optimism.

Artist Lee Quiñones stars as Zoro, an outlaw graffiti bomber who works solo, still sore about his breakup with an ex (Lady Pink) who’s gone legit, working on canvas commissions with a collective known as the Union. There are about half a dozen story strands that start like this but never really go anywhere in “Wild Style,” with quickly forgotten rivalries and romantic entanglements discarded in favor of depicting a time and a place at the cusp of a moment. With a little bit of hustle, these strivers from the South Bronx and their slick manager Phade — portrayed with boundless charm by Fab 5 Freddy, who also served as the film’s musical director — gain their introductions to the exclusive art world via an enthusiastic culture reporter (played by Fun Gallery founder Patti Astor, an early booster of Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat.)

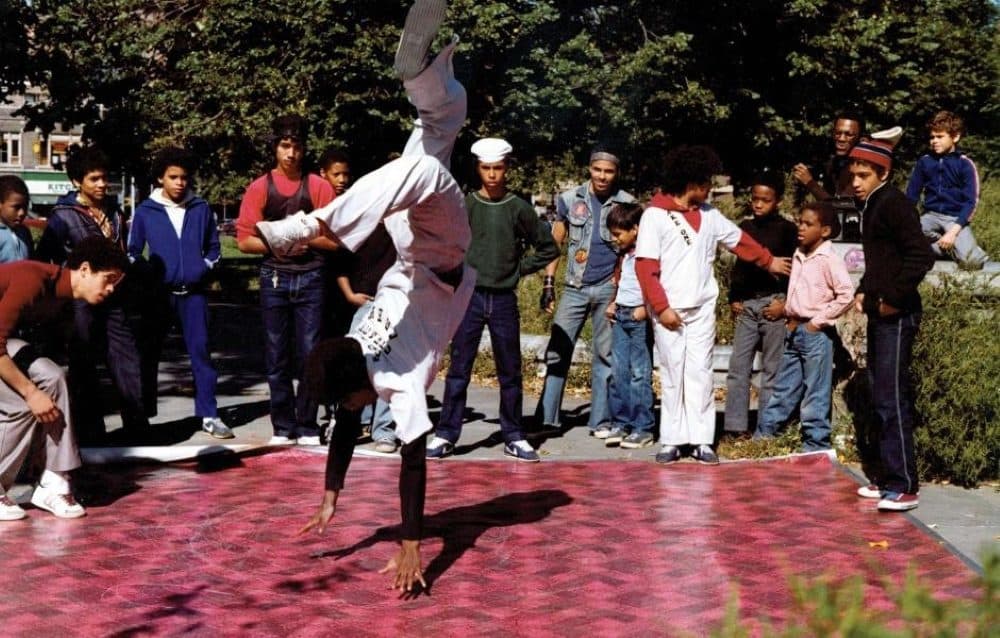

The dramatic beats are largely ad-libbed excuses to get to the next musical number or painting sequence. (Freddy has said that well-bred white boy Ahearn couldn’t write street slang to save his life, so they all ended up improvising.) You wouldn’t have to cut much connective tissue to turn “Wild Style” into a straight documentary, as what’s important here is the lifestyle and the lingo, with a whole new genre of music and dancing that had never been seen before on movie screens. It’s a kick to look back at Vincent Canby’s original New York Times review, in which the film critic attempts to explain rap to the paper of record’s readers, describing it as “a very particular kind of musical communication, in which the singer, backed by a monotonous, rhythmic beat, talks in rapid, always nervy rhymes that proclaim the singer's superiority in one sort of endeavor or another.” Not bad.

More from WBUR

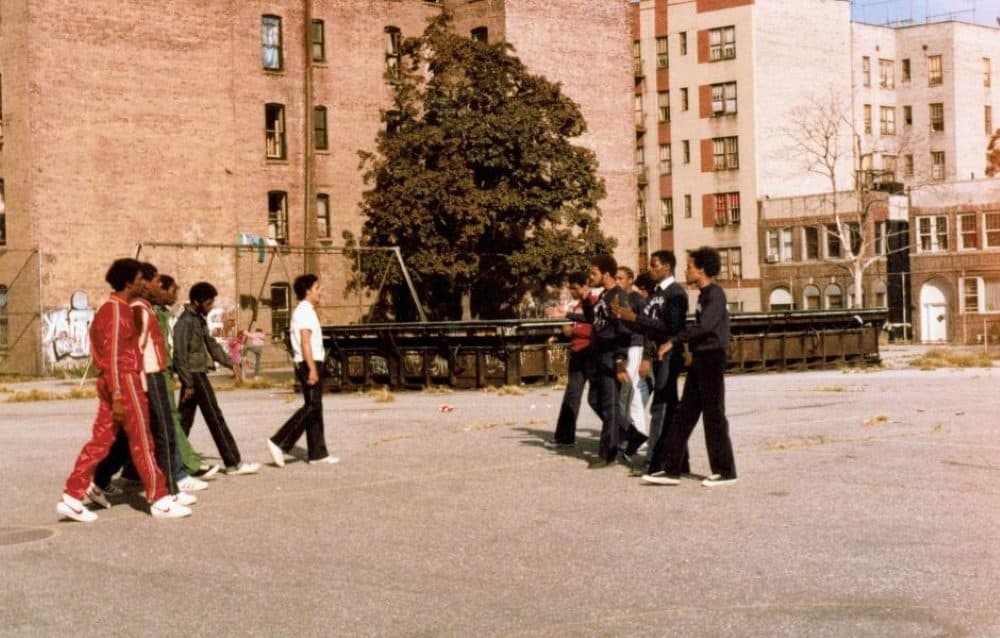

You also have to remember how at the time these neighborhoods were being depicted in Hollywood movies as barren hellscapes defended by burnout cops like Sylvester Stallone in “Nighthawks” and Paul Newman in “Fort Apache the Bronx.” Blondie’s Chris Stein — who helped compose the score to “Wild Style,” which is why you keep hearing “Rapture” — famously said the place looked like Dresden after the firebombing. But in this film, the mean streets are a sunny wonderland where anything can happen. What we worry is going to be a gang fight turns into a rap battle that becomes a pickup basketball game. The only time a gun gets pulled in the movie it’s a comic misunderstanding, with the rich girl reporter exclaiming, “Wait’ll I tell my friends we almost got killed! They’ll be so jealous!” (In actuality, Astor was significantly less enthused to learn that her co-star in the scene had brought his own prop.)

When “Wild Style” opened in Times Square in late 1983, it became the second highest grossing movie in New York City, behind “Terms of Endearment.” Imitators were soon waiting in the wings. Hot on its heels came the more hard-edged, rigorously plotted “Beat Street,” then the tireless trend-spotters at Cannon Films cranked out both the kid-friendly “Breakin’” and its notoriously-titled sequel “Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo” in May and December of 1984, respectively. (For my 10th birthday, we rented “Breakin’” and tried to mimic the moves on a piece of kitchen linoleum one of my friends had brought to the party. I don’t think I ever once managed to breakdance without injuring myself somehow.)

Some of the films that followed may have been flashier and more formally accomplished — “Beat Street” is actually quite good — but they’re missing the rough-and-tumble DIY spirit of “Wild Style” and the effortless authenticity of these first time actors mostly just being who they are. (Everyone in this movie seems to be wearing their own clothes.) The final set piece finds Zoro learning to set aside his chip-shouldered individualism and fully join this community during a dazzling outdoor concert in an abandoned amphitheater under a graffiti-painted hatch shell. This euphoric finale features performances by Kool Moe Dee, Double Trouble and the Rock Steady Crew, and if you squint your eyes just right while watching it you can see modern music being born.

“Wild Style” screens at the MFA on Sunday, July 25.