Photographer Philip Keith Is Capturing The Full Human Experience

It was December of 2019 when Philip Keith made the decision to quit photography.

“I was sitting in Harvard Square with a friend, and I told her, I was like, ‘I'm going to give photography one more year before I get a real person job,'” he recalls.

It’s funny to hear Keith say this now. If his bylines are any indication, he’s one of the Boston area’s most in-demand photographers. He strings for the New York Times and the Washington Post. He photographs celebrities for glossy magazines. He was even profiled in the Boston Globe last year for his coverage of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests.

The ARTery's weekly newsletter is your essential connection to Boston's arts and culture scene. Sign up here.

All that was beyond a distant horizon back in 2019. Keith, who is from Milton, became interested in photography as a student at the Boston Arts Academy. He worked for a while as a retoucher for a fashion startup in Boston before moving to Berlin on an artist visa. There, he found a vibrant art scene and work assisting fashion and automotive photographers. But he struggled to get gigs when he returned home. Instead, he found work as a barista — a cushy job at Google with benefits. But it wasn’t exactly the dream.

Then, in March of 2020, came the pandemic. A job Keith planned to start, at a new restaurant, was put on pause as the state went into lockdown.

“And so I was just home, and trying to find something to do with my time,” he says.

Video footage of the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin went viral that May, and protestors flooded downtown Boston. Keith grabbed his camera and hit the streets. “Not necessarily because I am a photojournalist,” he explains, “but just because I wanted to go out and use my camera.” He was tired of sitting around at home, twiddling his thumbs.

At that first protest, Keith snapped a photo of a protestor's raised fist sticking out a car window, silhouetted against a starless sky. Bloomberg Businessweek ran it on the cover.

That’s when things began to change. “I did find that I sort of had an eye for [street photography]. And a lot of editors and art directors saw that as well,” Keith says. “From there, I was getting these really big cover assignments, loosely pertaining to public health or the Black Lives Matter protests.”

Advertisement

“I seek to have my work encompass more of the Black experience...I don’t want it to be focused just on this moment of struggle.”

Philip Keith

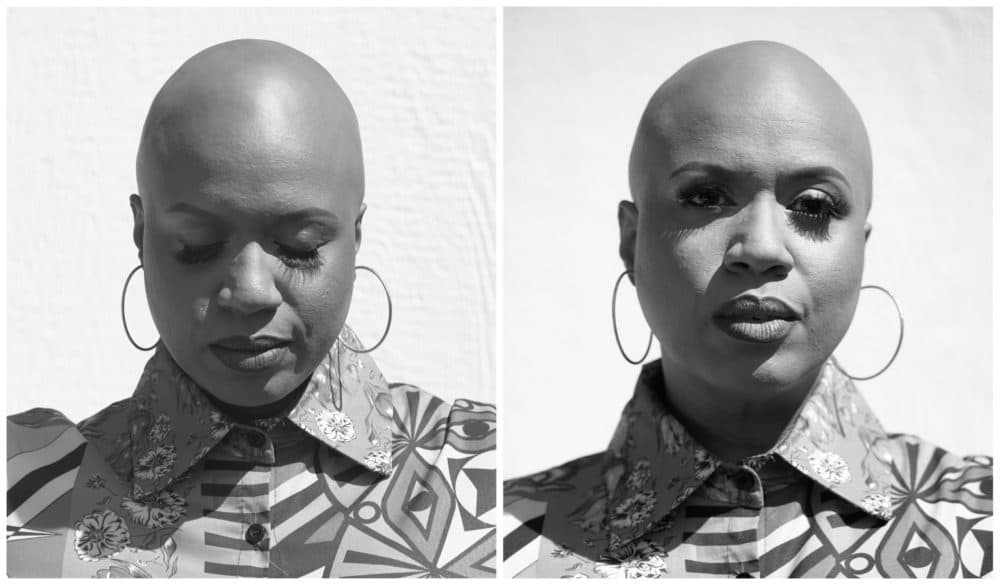

It was around this time that I started following Keith on Instagram. He was one of a few young Black photographers who seemed to be at every protest that summer, providing a constant stream of images to keep the uprising present in our minds. Keith was adept at conveying the fury and energy of the protests. But he also had a knack for capturing moments of stillness, of repose, amid the tumult. Then, gradually, his feed began to fill up with portraits of high-profile people for high-profile publications: Cornel West, looking irrepressible in a three piece suit, for the Guardian. A black-and-white closeup of Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, the sunlight casting dramatic shadows on her face, for Rolling Stone.

When I first contacted Keith, I suggested we meet up for the interview along the route of one of last summer’s marches. But he tells me he doesn't want to be defined by his protest photos. “I seek to have my work encompass more of the Black experience — or more just the human experience,” he says. “I don’t want it to be focused just on this moment of struggle.”

In the end, I meet Keith on a brutally hot August day while he is on assignment in Lynn, photographing a Project Bread truck giving out food to residents — the first of two photography gigs that day. He seems pretty busy, I observe. “I hate it,” Keith deadpans. Then he laughs. “I mean, I love it. It's really, really nice. I mean, it's just been such a crazy few years. Like, last year, when everyone else was not working, I was having my first busiest year.”

At least now he can afford to turn down assignments that don’t pay well or don’t interest him. He says he’s been taking more commercial work. It’s more lucrative, for one thing. Plus, “I get more of the creative direction,” he explains. “I’m still making portraits, and that’s primarily what I want to be doing.”

Portraiture is Keith's true calling. He likes to draw people out, disarm them. When I ask if he has any favorites from the past year, he mentions a photo shoot with John Kerry for Rolling Stone’s climate issue. “He’s, like, a good-looking guy,” Keith says. “He’s getting a little bit older, though, so he’s got a really interesting face.” In the photos, light from a window casts Kerry’s face partially in shadow. There is a gravity to the images, but a softness, too.

"The images are just so full of joy and people being comfortable in their skin...It's sort of like this reprieve from the rest of the world."

Philip Keith

This summer, Keith started a new project that he hopes to turn into a book. It’s about a historically Black beach on Martha's Vineyard called the Inkwell. The beach functioned as a haven for middle and working-class African Americans during the era of segregation. Today, it's a popular spot for Black residents and vacationers.

"The images are just so full of joy and people being comfortable in their skin, being out in public and on the beach and just, like, letting loose," Keith says. "It's sort of like this reprieve from the rest of the world. And I think that that's just as important as showing the protest side of things and the struggle and the pain that the community has endured."

The Inkwell has already been photographed a lot, which presents a bit of a problem.

“Aesthetically, for this project, I'm having a difficult time of how I want this to look,” Keith says. “Because a lot of people have made photos about the Inkwell, but they just make portraits of Black people on the beach. And it's like, that's cool. That's all well and good, but it doesn't really tell any story.”

Keith wants to show something different, to somehow gesture at the history of the place through portraiture. He’s been studying the work of photographers like Juan Brenner and Gregory Halpern, whose documentary images often seem to contain hidden imagery or double meanings.

“There's sort of a duality in the images,” Keith says. “Where you're seeing the thing that's photographed, and you begin to have a conversation with that, but there's a lot more about the story.”

Keith says he hasn't quite figured out how he'll achieve this in his photos of the Inkwell. But I think he's closer than he realizes. One of my favorite photos is one he took at the beach this summer. In the foreground, a paddleboard is frozen, mid-capsize, against the vast backdrop of a placid ocean. A boy in blue swim trunks and scuba goggles has flung himself into the air — back arched, arms outstretched, about to belly flop. Or he might be about to take flight.