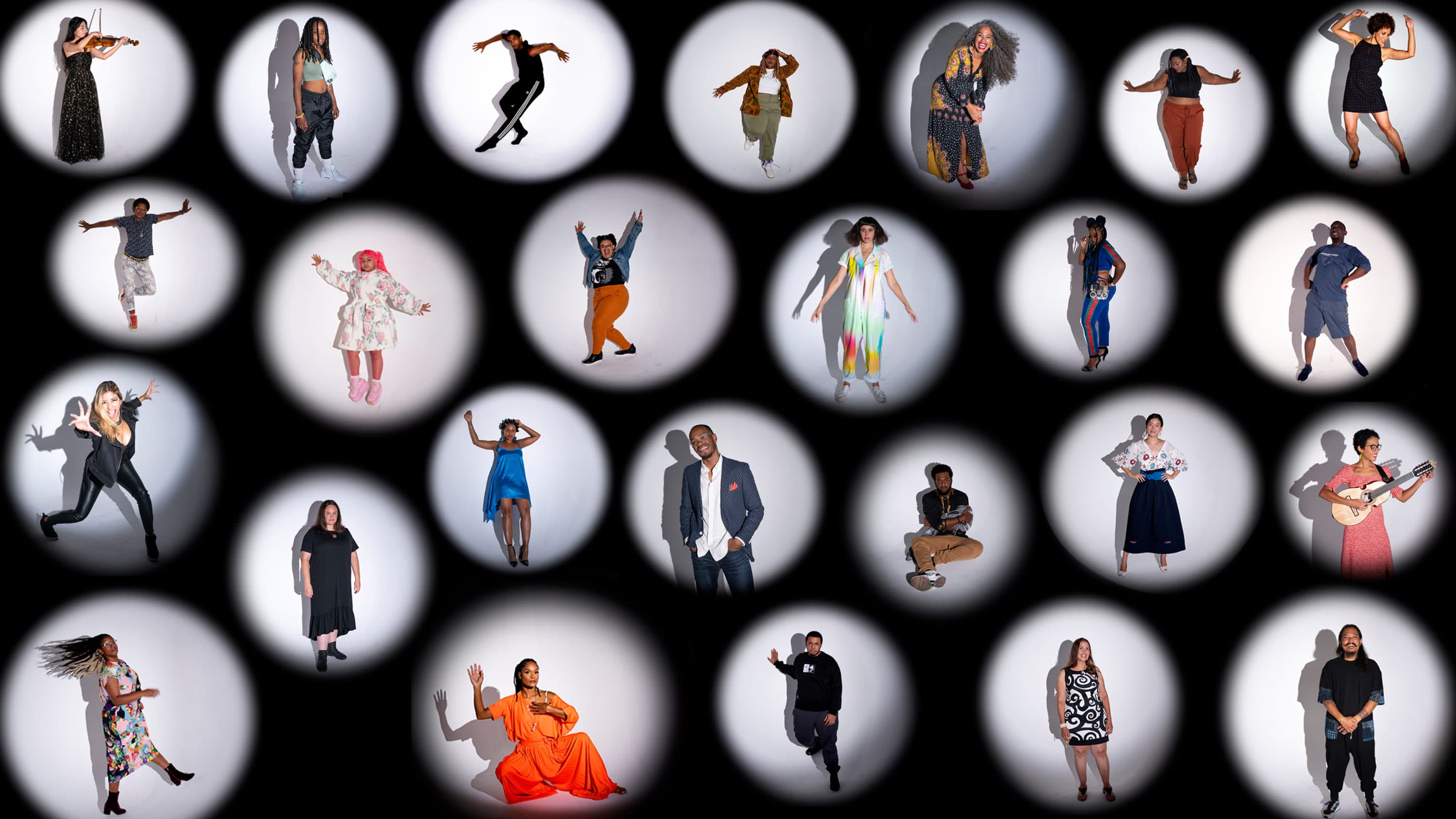

Meet The ARTery 25 — Artists Of Color Transforming The Cultural Landscape

Art lets us see the world through someone else’s eyes. And in a time where the pandemic has seemingly made life flatter, these artists bring a punch of fresh energy to the world around us.

For the second time since 2019, we are thrilled to present The ARTery 25, Greater Boston artists of color who stand out for the work they are making. Each one brings tenacity and rigor to their art, whether it’s on the stage, on a canvas, or served up on a plate. They uplift those in their orbit, and deliver an incisive perspective on the world around them.

We deliberated for months over whom to include, and convened an advisory panel of Catherine Morris, Layla Bermeo and Rob Gibbs to weigh in. We ultimately chose these creatives for their body of work, but particularly for the work they are pursuing at this moment in time. They bring a particular urgency to their chosen mediums, wrestling with issues of identity, race, equity and environment. And they come from different corners of the cultural landscape, some working independently and others as part of well-established organizations, like the Boston Ballet, MIT and the Museum of Fine Arts.

Artists of color, more often than not, are underappreciated. This is a group worthy of our attention, weaving their drive with their vulnerability to show us who they are. Each one inhabits a distinct moment in their career, ascending in their art with the promise of more great work to come.

—Tania Ralli, Assistant Managing Editor for Arts & Culture

The ARTery's weekly newsletter is your essential connection to Boston's arts and culture scene. Sign up here.

Meet the ARTery 25:

Allegra Fletcher | Amanda Shea | Anthony Peyton Young | bashezo | Biplaw Rai | DJ WhySham | Elbert "EJ" Joseph | Elisa Hamilton | Elizabeth James Perry | Erin Genia | Fabiola Méndez | Haydee Irizarry | Joelle Fontaine | Kadahj Bennett | Lawrence Rines | Michelle Villada | Nicole L'Huillier | Oompa | Pascale Florestal | Philip Keith | Rayna Yun Chou | Red Shaydez | Tonasia Jones | Woomin Kim | Yara Liceaga-Rojas

Allegra Fletcher

At the core of everything Allegra Fletcher does is a focus on justice and equity. The Afro-Caribbean Latina singer-songwriter, creative writer and multimedia artist has brought this passion with her as she has led worship in more than eight languages and written songs in English, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese. It showed up this year as she launched into her second master's in theological studies at Boston University, where she’s exploring colonial anti-racist work within institutions as a whole and, specifically, the church.

“I'm a progressive Christian, but I'm still a Christian,” she says. “And there's a lot of that history in that tradition that has to be grappled with.”

Fletcher served as executive director of Arts Connect International up until the pandemic. Then the organization took a step to re-examine their work. In that space, she realized something.

“I said, ‘OK, I really care about the interpersonal and I care about the systemic,’” Fletcher recalls. “And so I would like to focus my scholarship and my research not just on the arts and culture sector, but at the level of faith practice, because that's identity work and community work.”

Advertisement

Her work has always been interdisciplinary, and she pulls on her earlier studies at the Harvard Graduate School of Education where she earned a master’s in arts education. Now, she will focus her research on unpacking and interrogating some of the most problematic aspects of her faith.

“Jesus was a refugee, was broke as a joke and was part of an oppressed community at many levels. And you have people who are not oppressed reading themselves into the story as if they were,” she says. “I think that's where a lot of misapplication of the Bible has happened. I think that there's a different reading. There is a better narrative, a more loving narrative that can come from the text. And so that's what I want to do.”

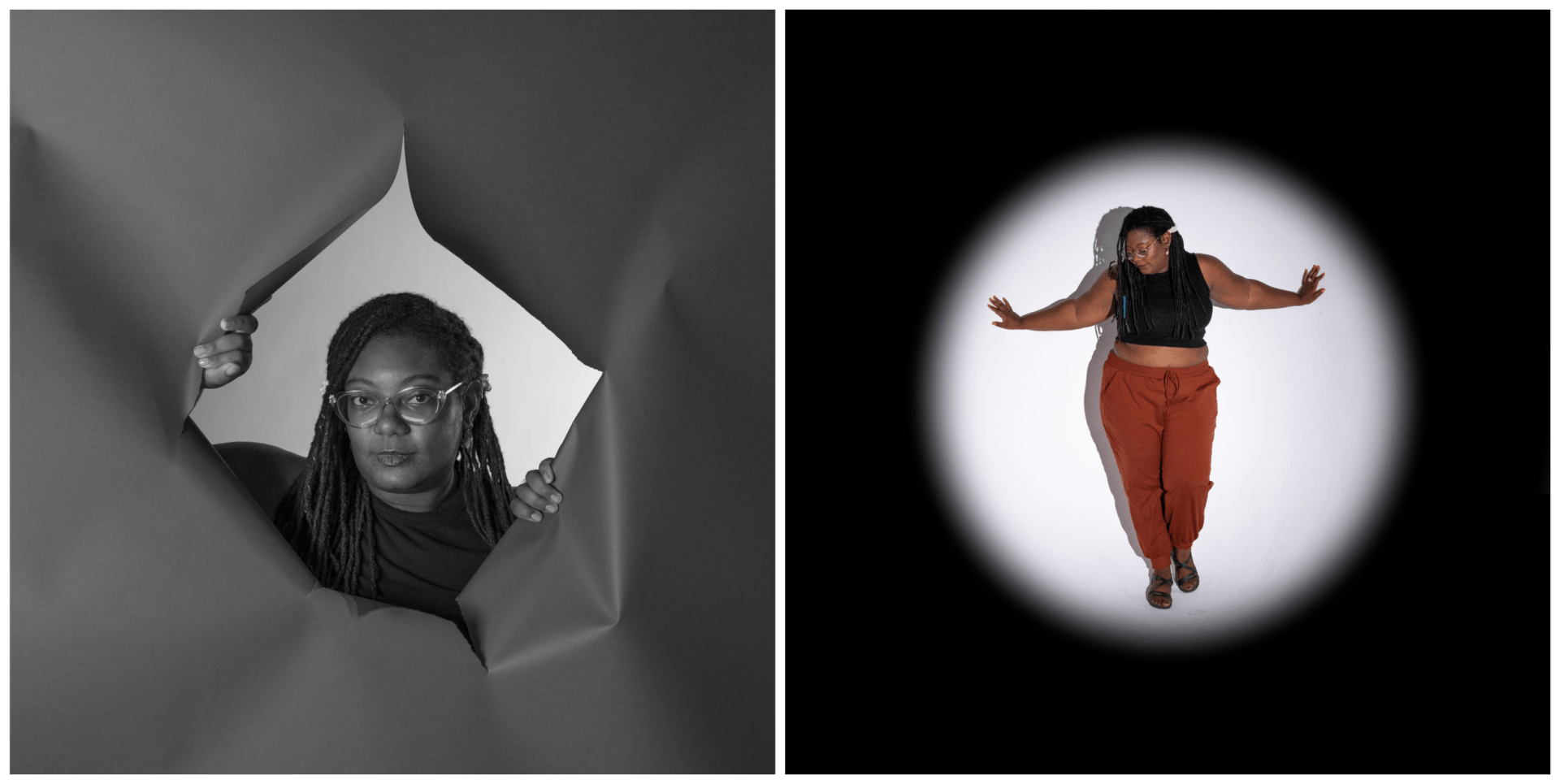

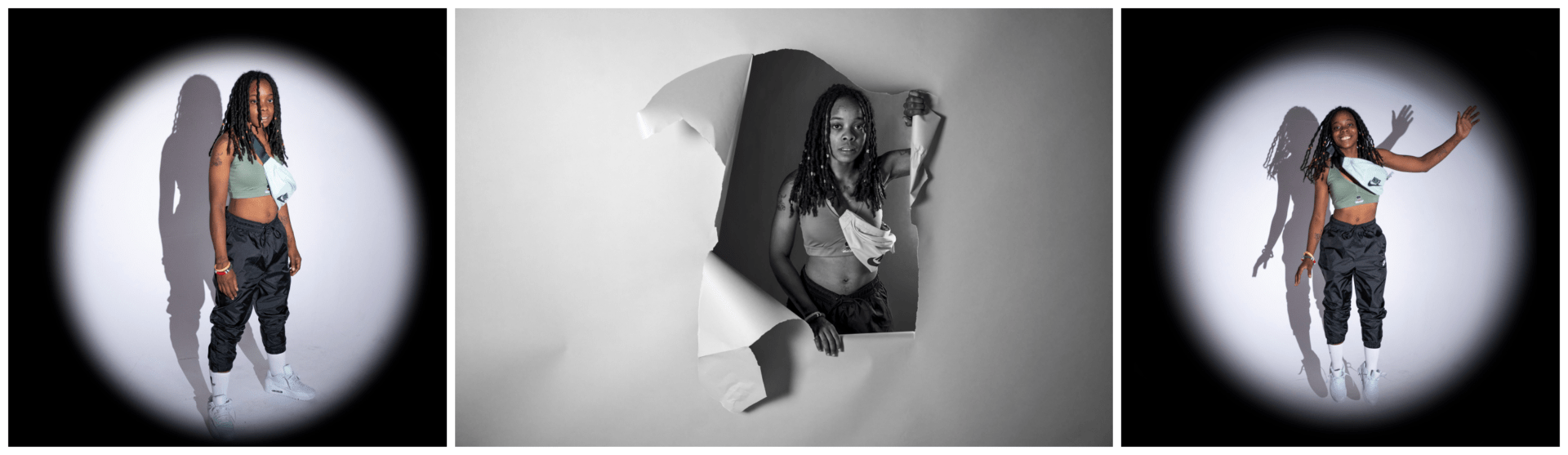

Amanda Shea

Amanda Shea is a self-described “artivist.” “I do raise awareness, I do protest, I march,” she says. “I do all of the things that an activist does. However, I use my art to protest.”

The educator and mentor weaves her writing throughout her work — creating poetry, visual and performance art. Shea also uses her work as a vehicle for healing.

Earlier this year, Shea released a video poem series called “Pieces of Shea,” exploring Blackness and womanhood. In one of the installments entitled “BODY,” she discusses her experience in the healthcare system as a Black woman, and in another — “ENTANGLED” — she touches on the topic of divorce, infidelity and addiction. “I was so scared to put my truth out there,” Shea says. “And now, I'm just like, 'No one's going to tell my story better than me.'”

Four years ago, Shea left her well-paying job as an accountant to pursue a creative field. This decision was a big risk and came with a major pay cut. Although she faced many challenges, “that’s not my testimony today,” Shea says.

“I tell people all the time, I've sacrificed so much to be an artist. I've been homeless, I was married,” she says. “But I'll tell you right now, it's the best journey I've ever been on and I would never turn back.”

Shea doesn’t shy away from exploring taboo subjects. She has several pieces in the works sharing her experiences with sexual assault, abortion and rape.

“I just want to show artists that you don't have to conform to one specific art form,” Shea says. “You can infuse as many art forms as you possibly want, and you don't have to necessarily put yourself in a box, because the industry already does that for us.”

Anthony Peyton Young

Many artists have sought, through portraiture, to memorialize Black lives cut short by white violence. But few have done so with the power and care that Anthony Peyton Young brings to his “They Have Names” series. Each portrait is a collage of many — a collection of faces fractured and reassembled into a jagged, prismatic whole. The intent is twofold. “I was really trying to think of the collective loss that we experience as a group of people,” Young says. But the line between honor and exploitation, he knows, is perilously thin: “I think that it’s really hard [for a victim’s family] to see their face plastered everywhere and have that constant reminder.” In Young’s tributes, the identities of his subjects are at once preserved and obscured.

Young grew up in Charleston, West Virginia and loved to draw from a young age. After moving to Boston to attend the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, he began to experiment with new materials, like gunpowder and bleach. Young likens the destructiveness of these methods to the violence depicted in his paintings — the corrosive effects of homophobia and white supremacy. But the throughline in all his work is generative, he says, not destructive. This is perhaps most apparent in Young’s sketches of Black and brown members of his queer community, rendered tenderly in soft pencil lines. “All of the work is focusing on this one core thing,” Young says, “of community, family and the intimacy within those.”

bashezo

bashezo has had many names. They’ve lived in many places. The trans nonbinary artist grew up in South Philadelphia, moved to California and eventually found their way to Boston to study. They’re a space holder, a Lucumí priest, a sculptor, performance artist, and lover of tile work and mosaics. They are a member and co-founder of the UnBound Bodies Collective, a group of queer and trans creatives who find new ways to express themselves through their art.

“We're still kind of unpacking and dismantling the ways in which we are confining ourselves, our bodies, our beings in these bodies,” they say, “and wanting that for ourselves, wanting that type of liberation for ourselves and wanting that for other folks.”

They laugh when I ask them how many times they felt they have come out. At almost 50, they’ve shed so many layers and continue discovering who they are.

“It's been amazing to be in conversation with so many young Black trans folks who, at 20, are able to articulate and be with themselves in ways that I yearned for and longed for, but didn’t have the vocabulary, didn't have a community, didn't have the support,” bashezo says. “I was moving and working my way to that, kind of blindly...and falling off lots of cliffs.”

But still, they found their own way, their own path, combining spirituality with art, building living altars that uplift and honor queer trans folks in this life for a project called Roots + Futures.

“Our lives and our experiences are so important,” bashezo says. “And it's important that they're told with nuance and with honesty and with love and with care and not extractive...as well as not fixed. These are stories, but it’s not all of who I am or what I’m yet to uncover about myself.”

Biplaw Rai

Biplaw Rai brings people together with comfort meals at his pop-up restaurant inside of Little Dipper in Jamaica Plain. Named Comfort Kitchen, the pop-up has been around Greater Boston since 2020, and has been serving up global cuisine four nights a week in JP since this past spring while their permanent home is being built in Dorchester.

Comfort Kitchen incorporates ingredients from the African Diaspora, Caribbean and South Asia and the spice trade. “We bring a very global perspective to our dishes,” Rai says. “And what we find out is there's more commonality than differences in food.”

Rai immigrated to the U.S. from Nepal when he was 18 for college. His first jobs were in places like Taco Bell, KFC, and in the summers he worked in Ocean City, Maryland with other Nepali college students. He saw how much the restaurant industry relies on immigrants, and how often employers fail them.

“For a long time, while we were working in the restaurant industry, our voices or our stories were never heard,” Rai says. “Or if it was heard, it was never the center of it. And I've always said that the restaurant industry is like the underbelly of the United States.”

Rai aims to create a space that values cross-cultural understanding, community and collaboration. At the restaurant, he has cultivated an environment where staff share meals before their shift and also help newcomers get settled. In the community, Rai is also a trustee for the Grove Hall Trust, an organization that is dedicated to improving the quality of life in the Dorchester neighborhood.

“There are places that people don't feel comfortable walking in. It's mostly got to do with class and the money,” Rai says. “We want to be just the opposite of that. We want people from all walks of life to come in.”

DJ WhySham

Dorchester-native DJ WhySham learned the basics of her musical craft while attending Cedar Crest College in Pennsylvania. She learned how to make a playlist as well as some rudimentary radio skills.

When she came back to Boston, WhySham put her developing DJing skills to use in the poetry scene. She DJed for her roommate, Boston Poet Laureate Porsha Olayiwola, during open mic nights at Roxbury’s Haley House Bakery and Café, and also toured with poets to national competitions.

“I just had a real urgency to be a part of a community,” she says of this time.

In 2018, WhySham created Boston Got Next, an organization “by womxn, for womxn” that teaches youth and adults basic engineering. One of her goals is to create equality in the music industry.

“You see a female and a guy, you're going to think that the guy's a rapper,” she says of stereotypes in the industry. “You see me, you're going to think that I'm, like, the roadie or just a random girlfriend or something like that. But I'm the actual DJ.”

But she tries not to dwell on that, instead focusing on the music. WhySham refers to herself as a "community DJ," playing a range of events, from weddings and parties to funeral services. She has also DJed for Boston Centers for Youth and Families and other local nonprofits.

No matter the event or location, WhySham brings her observant nature to every gig. Her perception is her strength; she is always able to generate a comfortable atmosphere.

“I can be in a room with 100 people, 250 people, five people,” Why Sham says. “If one person came up to me and said, ‘I enjoyed the music,’ that makes my day.”

Elbert "EJ" Joseph

Onstage, actors are often told to project to the back of the room. Make sure the audience can hear and see you. Capture them with your delivery. Elbert “EJ” Joseph emotes to the back of the room. An actor who is hard of hearing, his facial expressions, mannerisms and body language all speak volumes. He’s used to using his body in conversation through sign language. Acting -- and now directing -- is simply another medium, a conduit to communicate.

“I've been acting since I was 14 years old,” Joseph says. The show that inspired him as a teenager was “Peter Pan,” performed at the Wheelock Family Theatre many years ago. The actress who played Wendy, Amanda Montgomery, happened to be Deaf, like Joseph. He watched her perform alongside a cast of Lost Boys, who signed as they sang the song “I Won’t Grow Up.” He was mesmerized. "That’s when I knew, 'You know what? I can do this,'" he says. "'I belong onstage.'"

That sparked his professional career. He is now an actor, director and consultant. Some of his roles include Louis in “The Trumpet of the Swan” at Wheelock Family Theatre, Yeffirm in “Uncle Vanya” at American Repertory Theater and Tuc in Suzan Zeder’s Ware Trilogy: “Mother Hicks,” “The Taste of Sunrise” and “The Edge of Peace.” Joseph says he’s always looking for a good role and would love to see more main characters who are Black and Deaf, because you rarely see them represented onstage. He wants theaters to think outside the box.

“There are many ways to tell a story through the character,” he says. “To make the audience think, 'Where have I seen, or how do I know someone exactly like that?' To relate to the experience. People need to see a reflection of something that they've experienced, even if it's a different kind of culture, a different kind of person with a different type of personality. We should be able to give audiences food for thought. You have to take risks. The audience needs to be challenged.”

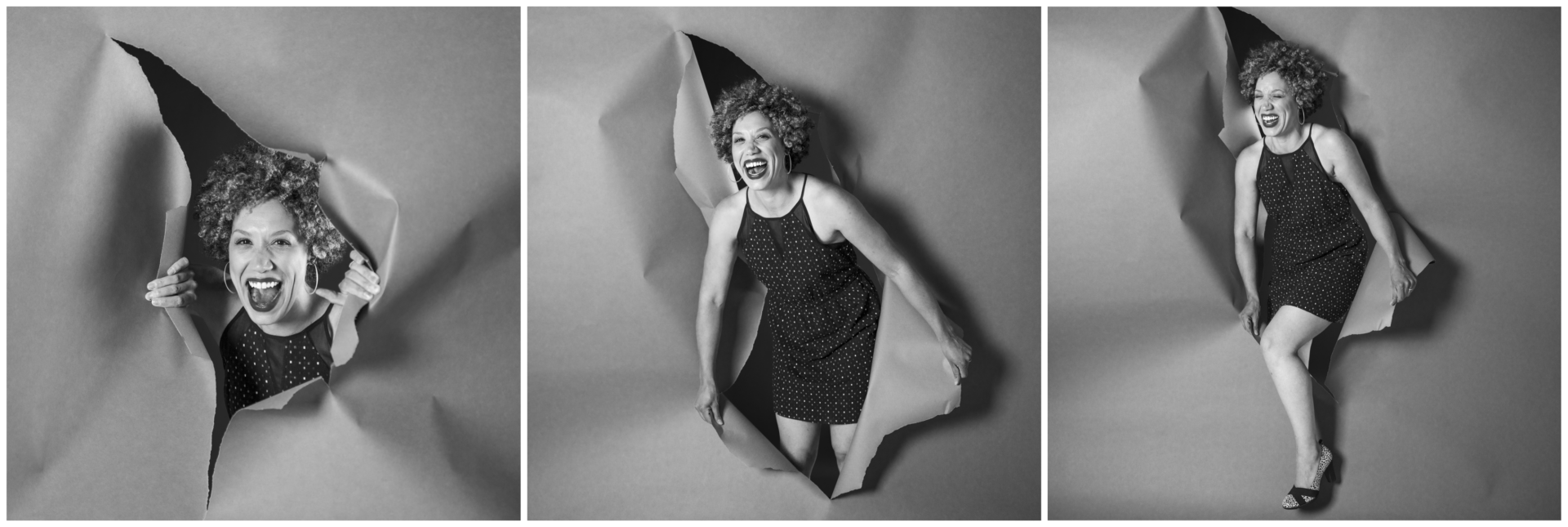

Elisa Hamilton

Before 2012, artist Elisa Hamilton made paintings and drawings she hoped would capture joy in ordinary moments. For example, “dishes in the sink can be beautiful,” she says with a laugh.

But what Hamilton really wanted was to find ways to bring those feelings off the gallery wall, “and into a place where people could experience it together in a surprising way.”

Then she had a vision. Hamilton pictured rush-hour pedestrians and wondered what would happen if she invited them to let loose — even for a minute — and just dance. With help from a small grant, Dance Spot was born, enabling Hamilton to transform sidewalks into dance zones around Fort Point in Boston.

“That was the moment,” Hamilton remembers, “when I realized I can make people laugh and smile with my art.”

A decade later, the 38-years-old's portfolio brims with the successful social engagement projects she's now known for: a roving lemonade cart where public housing residents shared stories about overcoming challenges; a “store” at the Boston Center of the Arts that sold superpowers and explored ideas of heroism; a Sound Lab where Hamilton collaborated with community organizations to help residents record sounds from their lives and press them onto vinyl records.

But the pandemic and racial justice movement spurred the public artist to confront her own story. “How can I ask people to share their experiences if I'm not brave enough to share my own,” she asked herself.

Hamilton grew up biracial/Black in a mostly white community. As a kid, she struggled with her hair behaving so differently than her friends'. So she created "Hair Care" paintings online where she wrote, “It took me over 20 years, but now as an adult, I love my hair; it has become the most wonderful connector between me and other biracial and Black women.”

Now, Hamilton is hitting the streets again for her postponed, community-sourced storytelling project called "Juke Box" that debuts next summer.

Elizabeth James Perry

Lifelong multimedia artist Elizabeth James Perry is on a quest to re-wampum the landscape of New England.

“It was very much the machine that kept things going that connected people through history and ceremony, and through treaty. Then a lot of it was confiscated or stolen,” James Perry says of the purple and white quahog shells used for thousands of years as jewelry and currency for Eastern Woodlands people. “To be able to produce wampum again, and have it live all over my homelands prominently, is actually really healing.”

James Perry is an enrolled member of the Aquinnah Wampanoag tribe and comes from a family of artists. A common thread through her work is sustainability and working with non-toxic materials, which is informed both by her cultural history and her education as a marine biologist.

“My work has been to revive certain art forms because of my drive to reclaim traditional technology and also my dedication to the environment,” says James Perry. “I've always encouraged those forms of creative expression to be made prominent, made accessible and reflected in Boston, which is a city that doesn't have much acknowledgment of its native presence.”

She’s noticed a change in the past few years as more people become aware of the role that Western imperialism and capitalism have played in creating the environmental crises we are facing. “Garden for Boston,” her recent installation at the Museum of Fine Arts, has transformed the landscape surrounding Cyrus Dallin’s “Appeal to the Great Spirit” statue, a stereotypical depiction that has greeted visitors to the MFA for the last century.

“I think that it's a time when artists don't necessarily have to put up with being ignored or marginalized or disrespected, because there's beginning to be a sense of accountability,” says James Perry. “People are beginning to get an idea that how you conduct yourself matters, how you treat people matters.”

Erin Genia

Erin Genia was born in 1978, the year the American Indian Religious Freedom Act was passed. The law at last allowed Indigenous people to practice the religions of their own cultures. Genia, a tribal member of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate of South Dakota, sees her artistic mission as one of many efforts to make up for the centuries of assimilation and cultural repression that preceded the passage of that law. Her work, she says, is guided by Dakota philosophies, particularly the idea of mitakuye oyasin, which loosely translates to “everything is related.” In this framework, “we’re related to the earth itself, to the rocks, to the air,” Genia says. “And because of that, everything has, or should have, its own agency, and everything should be treated with respect.”

Genia is a multidisciplinary artist with a background in sculpture and painting. She came to the Boston area to attend MIT’s Art, Culture and Technology Program, where her studies focused on Native American art in public space. “There’s a great deal of erasure of native and Indigenous people that happens in public space,” Genia says — like the historical markers peppered throughout the New England landscape, which so often trade in falsehoods and colonial mythology. In a GIF she created, Genia critiques these markers with lacerating bluntness. Phrases flash inside the image of a sign topped by the Massachusetts state seal: “INDIANS LIVED HERE NOW ITS A STRIP MALL;” “YOUR GENOCIDE WAS INCIDENTAL;” “SORRY.” The words generate their own disquieting rhythm, demanding that we not look away.

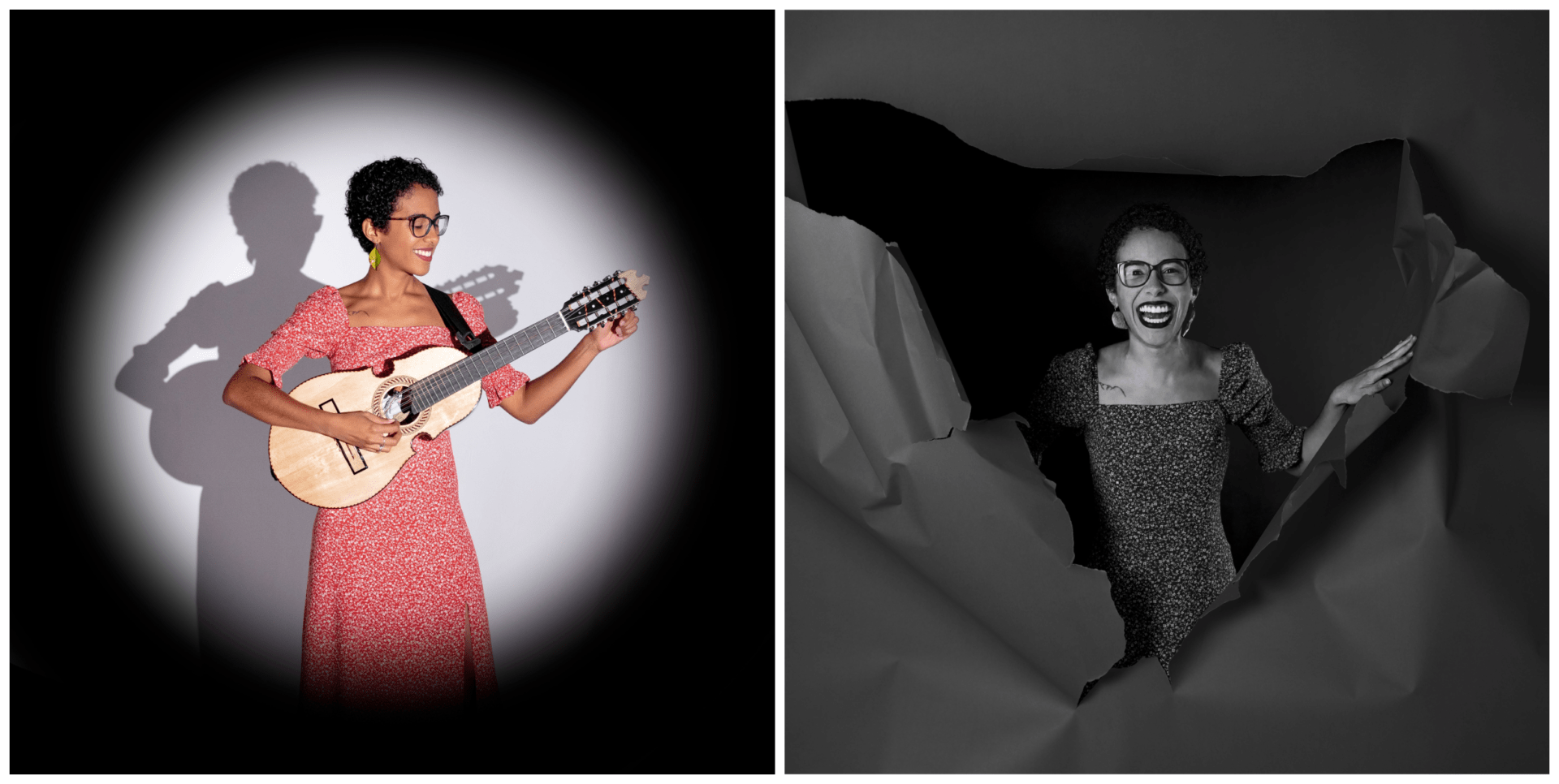

Fabiola Méndez

Before the Puerto Rican cuatro provided that twinkling, now-iconic intro to the international reggaeton hit “Despacito,” the guitar-like instrument was considered a bit of a relic. “I had so many friends who would tease me, and say, ‘Oh, Fabi plays that lame instrument. She’s like an old person,’” says Fabiola Méndez, who picked up the cuatro when she was six. Since then, Méndez has been on a mission to prove to the world — and, perhaps more importantly, to her own people — that the cuatro is an instrument of greatness. “The cuatro can be used in any context, in any setting, not just folk music,” she says.

Méndez, it should be noted, is very, very good at playing the cuatro. Since becoming the first student to major in cuatro at Berklee College of Music, she has released two expansive, jazz-inflected LPs. Her new album, “Afrorriqueña,” was inspired by the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020. “I was thinking about how that relates to me as a Black woman, but also as a Black Latina,” she says. “We like to think there’s no racism in Latin America… and it’s not the case.” The cuatro is the perfect instrument to deliver this message. “It was an instrument that was developed by Puerto Rican people during the periods of colonization,” Méndez says. “It represents our history.”

Haydee Irizarry

At 8 years old, Haydee Irizarry made a declaration that surprised her parents: “I want to be a metal vocalist,” she proclaimed.

Heavy metal might not be music to everyone's ears, but for most of her life the dark, brash genre has been the Salem-based mezzo soprano's chosen form of expression. When asked about her initial attraction, Irizarry says metal offered salvation and release as she struggled with her parents' divorce, an abusive brother and her mental health.

“When I was getting started, I really connected to the aggression because of all the things I was feeling at the time,” she explains. “I was feeling a lot of dark, intense things that I didn't really quite know how to express outside of music.”

Irizarry studied jazz, classical and contemporary music at Berklee College of Music where she also became lead singer of melodic death metal band Aversed. There, Irizarry honed a style that vacillates between “clean singing” and the guttural vocals many metalheads refer to as “the Cookie Monster voice.” The 26-year-old says the varied voicings enable her to tap into a limitless palette of textures and emotions.

“If I were a painter I could choose just the cool colors — that would be the pretty sounds — but I'm choosing all of them,” she says. “So how I would describe my voice is just all-out on the table.”

Irizarry's range and arresting stage persona have earned her a few novel nicknames, including Haydee the Hyena, Metal J.Lo and Metal Selena. She's Mexican-Puerto Rican and in performance also wears a lot of leather and spiky studs, plus bold colors on her eyes, lips and nails.

In 2018, Irizarry joined the Salem-based, stoner/doom metal band Carnivora as the group's first female front person. “The face of metal is shifting a lot towards women and women from all different countries that look so different,” she says. “It's awesome to be a part of that change.”

Joelle Fontaine

To understand Joelle Fontaine's creative journey, you need to learn about her mother’s. At 16, Yolette Fontaine used $500 and a passport to start a business that resold goods from Panama and the United States in Haiti. She also put herself through engineering school, became a teacher, a seamstress and opened a fashion boutique in Port-au-Prince.

But in 1987, political upheaval and violence destroyed everything Yolette had built. Fearing for their lives, she and Joelle fled to the U.S., where Yolette experienced racism, in part, because of her thick Haitian Creole accent. Now, Kréyol is the name of Joelle Fontaine's fashion brand that's inspired by her mother's resilience and homeland.

“The fabric of my culture is deeply ingrained in who I am,” Fontaine says. “When I started designing, I looked at old Haitian school uniforms for inspiration on silhouettes, prints, quality and construction, as well as colors and energy. I think my clothing has the energy of home.”

Like mother, like daughter. Fontaine forged her own career path. It kicked off when she was 23 after she submitted designs that earned her a place in New York Fashion Week.

“I had absolutely no idea what I was doing,” Fontaine writes on her website. “But I had passion, grit, talent and the audacity to believe I belonged there.”

Fontaine went on to design empowering, made-to-wear garments that fit each woman's unique body. She says it also helps reduce waste and her company's carbon footprint.

Kréyol is also a catalyst for economic mobility. The accessories Fontaine sells are made by female artisans in Haiti and Ecuador.

Looking ahead, Fontaine hopes to open a brick-and-mortar shop with her mother, who's co-seamstress at Kréyol, while expanding her roster of international artisans. “I'd like to show how a beautiful leather clutch can be the catalyst for an artisan to purchase her own home in Haiti and build a life for her and her children. I have seen what it looks like to survive. I want to give women the option to thrive.”

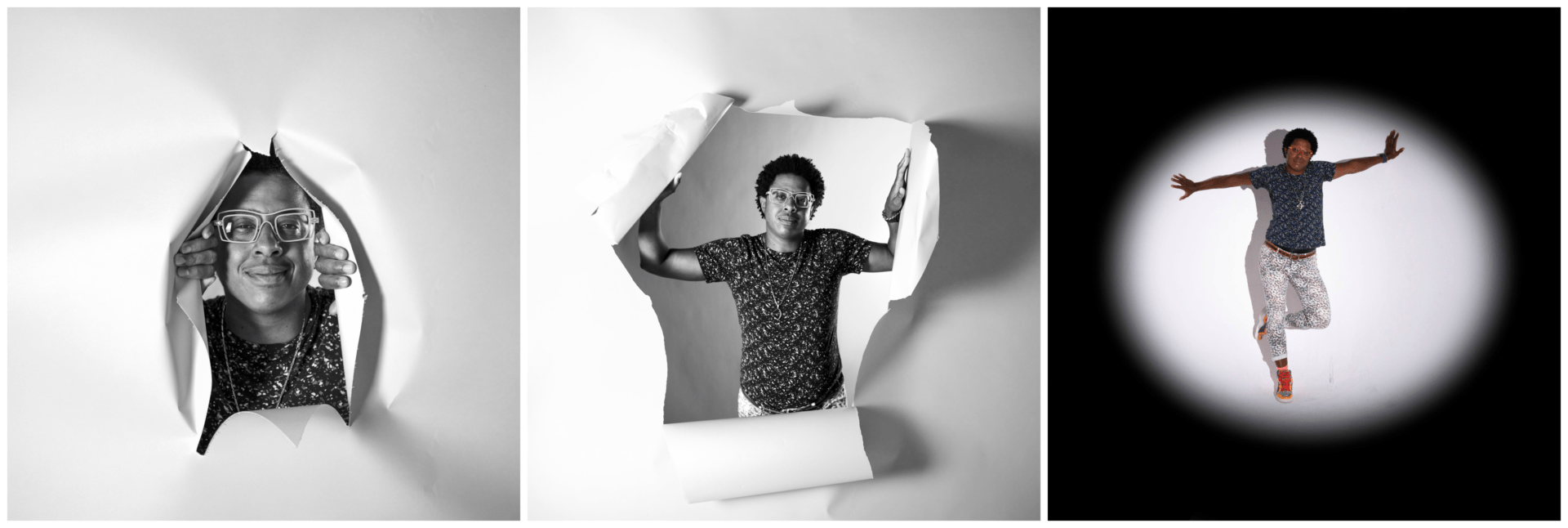

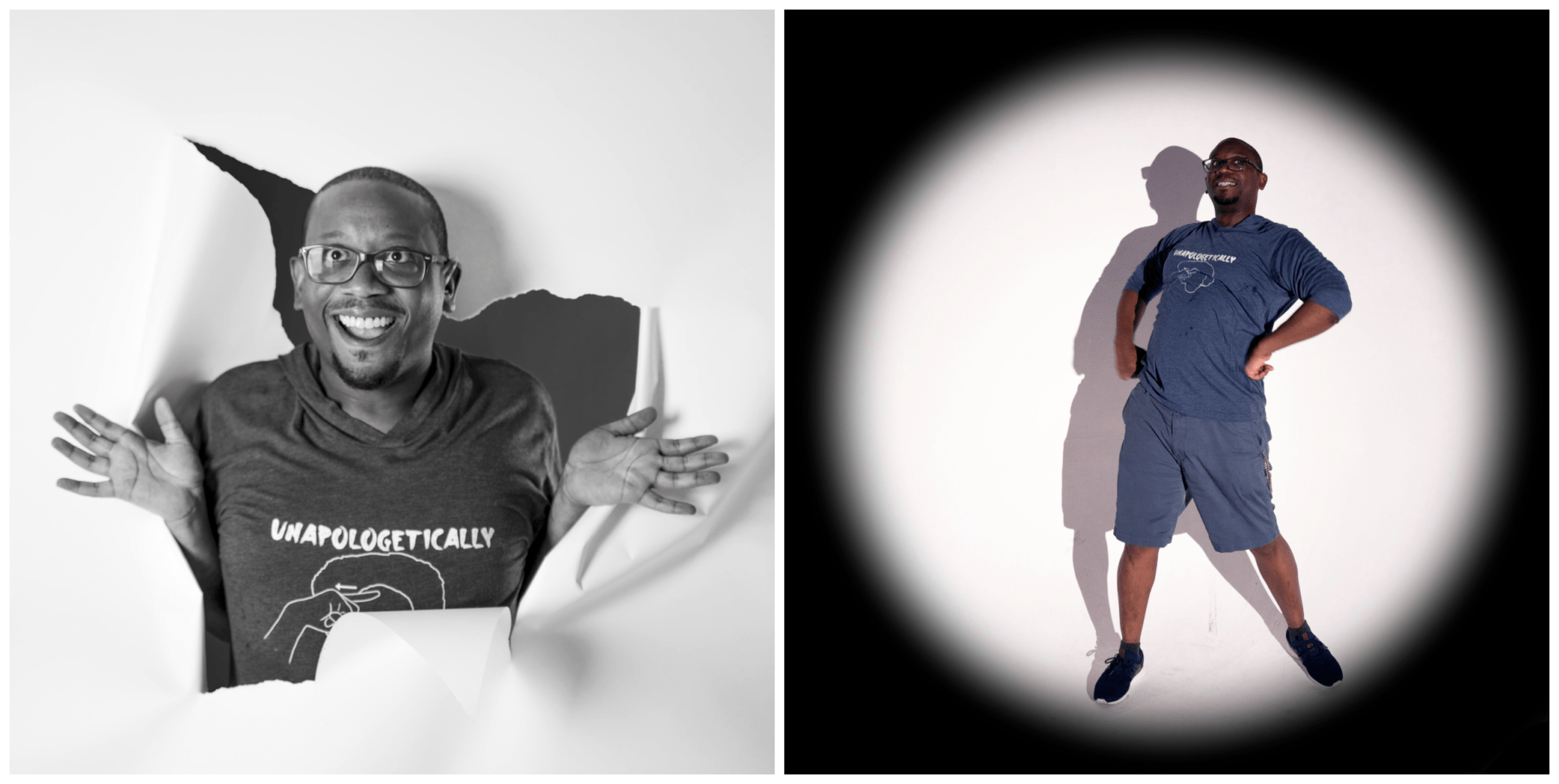

Kadahj Bennett

Kadahj Bennett has come full circle in his Boston arts career. The award-winning actor, teaching artist and musician started out as a student at the East Boston nonprofit ZUMIX when he was 13 and went on to high school at Boston Arts Academy. Now, he’s the songwriting and performance manager at ZUMIX and artist-in-residence at the First-Year Arts Program at Harvard University.

Bennett calls himself a “ratchetdemic.” He loves learning and history, and he doesn’t censor his authentic self, no matter the institution he’s working with.

“Everybody is allowing these unheard voices to step up to the microphone,” says Bennett, who felt like someone had dropped a magical letter into his mailbox when he was chosen as a luminary artist at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. “This place was down the street from high school and we walked past it all the time, but it felt like some foreign sanctuary. Now they’re asking me to do my art.”

Bennett hopes the changes he’s seen in institutions and their audiences are more than just a trend. Before the pandemic shut everything down, he reached a high point in his acting career when he played Moses in Speakeasy Stage’s “Pass Over.”

Bennett was surprised a Boston theater put on a play like that, saying when he first read it, he thought it was “absurd as hell.” But his performance landed him a 2020 Elliot Norton Award for Outstanding Actor in a Midsize Theater.

“To have the opportunity to dig my teeth into a character like Moses and have the opportunity to reflect people that I knew growing up here in Boston, Mattapan, Dorchester, Roxbury, that I feel are often not represented — that was an awesome touchstone moment.”

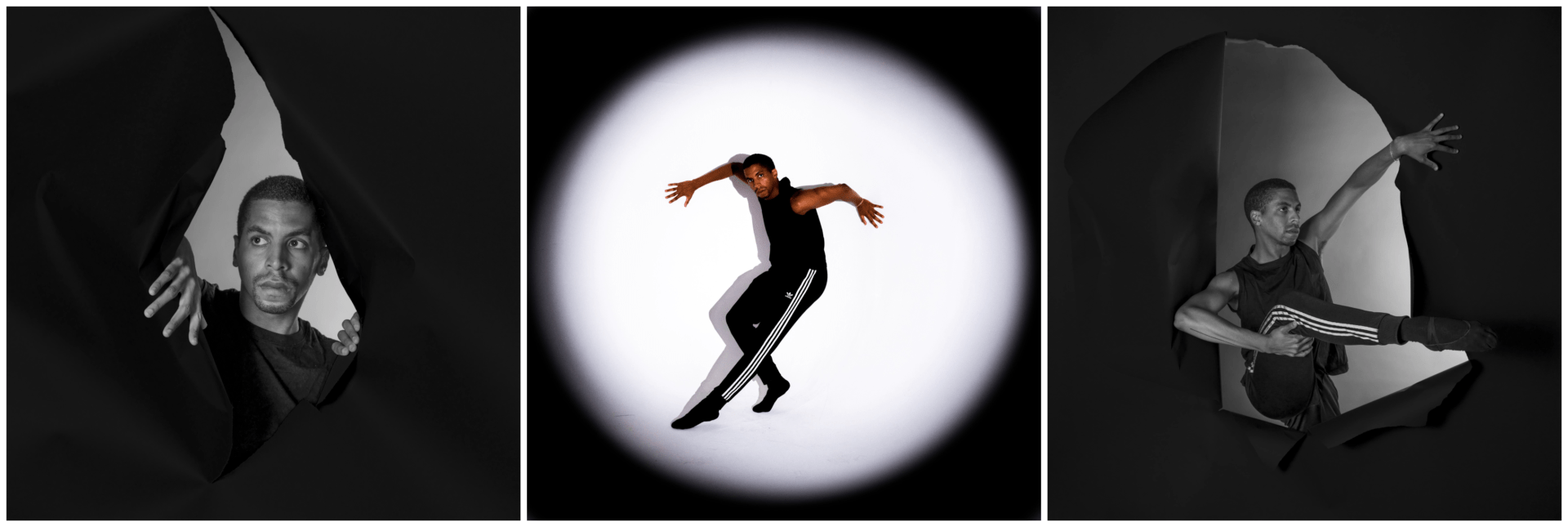

Lawrence Rines

When Lawrence Rines joined the Boston Ballet 12 years ago, he was the company’s only African American dancer.

“I would get interviews for being an African American dancer in a predominantly white company, and it opened my eyes,” says Rines. “I don’t think that I've been held back ever in my career for being a person of color, but it’s this strange pressure when you are the only person in your situation.”

Even still, Rines considered the Boston Ballet to be more diverse than other companies globally, and he says it continues to grow. Classical ballet has always had a problematic focus on one kind of perfection — a very upper class, Western/Eurocentric one — but the current cultural moment has forced those perpetuating these standards to adapt or get out.

“A lot of people in leadership haven’t welcomed the change, and they’re either stepping down or being forced to resign,” says Rines. “It's been an amazing shift, which I have enjoyed being a part of.”

Rines is a first soloist, the second-highest position in the company after principal dancer. While the pandemic has been difficult for the performing arts sector, Rines was grateful that the company continued with their season virtually. Still, he’s eagerly anticipating their return to the stage in front of live audiences with the annual holiday favorite, “The Nutcracker.”

“It’s a transcendent experience and it’s the reason why I'm in this artform,” says Rines. “When we finally have a live audience, the applause and the curtain calls and all of that, I think everyone onstage is going to be bawling. There's nothing really like it.”

Michelle Villada

Michelle Villada calls herself a maker — of fashion, costumes and “a little bit of everything.” A graduate of Framingham State University with a bachelor’s in fashion design and retailing, she’s been featured in Vogue Italia, The Boston Globe and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. She found a niche making intriguing face masks during the pandemic. It allowed her to use her skills as a designer to both provide safety and bring a sense of uniqueness to the act of covering one’s face -- something that had become a kind of drudgery.

“My art practice really grounds me and is also a really big source of catharsis, safety and refuge,” Villada says. “So I started really leaning even more heavily into it... It was like, 'Man, I really need to do something.' And the healthiest, most satisfying thing to do was to just make.”

She spent part of the pandemic making and walking with her grandmother in preserves across the state even in the dead of winter, finding inspiration in nature and in herself. Because, though fashion is not a biological need, she says, it is an emotional one. “It really speaks to something in our soul,” Villada says. “Everybody's in some sort of wearable art, whether they consider it that or not.”

The Boston-based Latinx fashion designer says she “fuses Harajuku fashion with internet culture, and a love for everything kitsch.” She strives to elevate queer folks, color outside the lines of gender politics and hopes that people feel free in her clothes. She’s currently working on making designs to dress a play with the Boston Conservatory at Berklee and a more experimental show coming which she calls a “theater runway extravaganza.” She also hopes to do pop-up shops, which will allow her to see and dress people in real life for the first time in a long time.

Nicole L'Huillier

Nicole L’Huillier is a multimedia artist from Santiago, Chile who’s in Massachusetts pursuing a Ph.D. at MIT’s Media Lab. Her work oscillates at the intersection of science, technology and art. It’s informed by research about the building blocks of the universe, from the smallest units to the expanse of the cosmos.

But she’s first and foremost “obsessed with sound.”

“Sound is a portal,” says L’Huillier. “A sound, for me, it's a way that we can engage with different multidimensional realities, what we call the pluriverse.”

Her traveling sonic sculpture, “La PARACANTORA,” has been installed at research sites like the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Switzerland, and the ALMA Observatory in Chile. The sculpture’s physical design is simple, just a tripod and horn speakers, belying its mind-bending function.

L’Huillier says it’s a note-taking device, collecting data and sonifying the seemingly invisible, abstract forces that shape our reality. Forces like temperature, altitude, pressure, wind, radiation and electromagnetic activity, translated into sound.

“It's a listening ritual,” says L’Huillier. “It is spiritual, but it's less tied to a system of belief or religion somehow, but tied to cosmologies. How do we form a part, how do we inhabit with and in this universe?”

She says her work offers a new point of view. It’s about unlearning society’s imbalances in order to confront the things that aren’t working well. She wants people to be flexible and dynamic as they engage in this dialogue. Her work reminds the audience that they too are just a vibration.

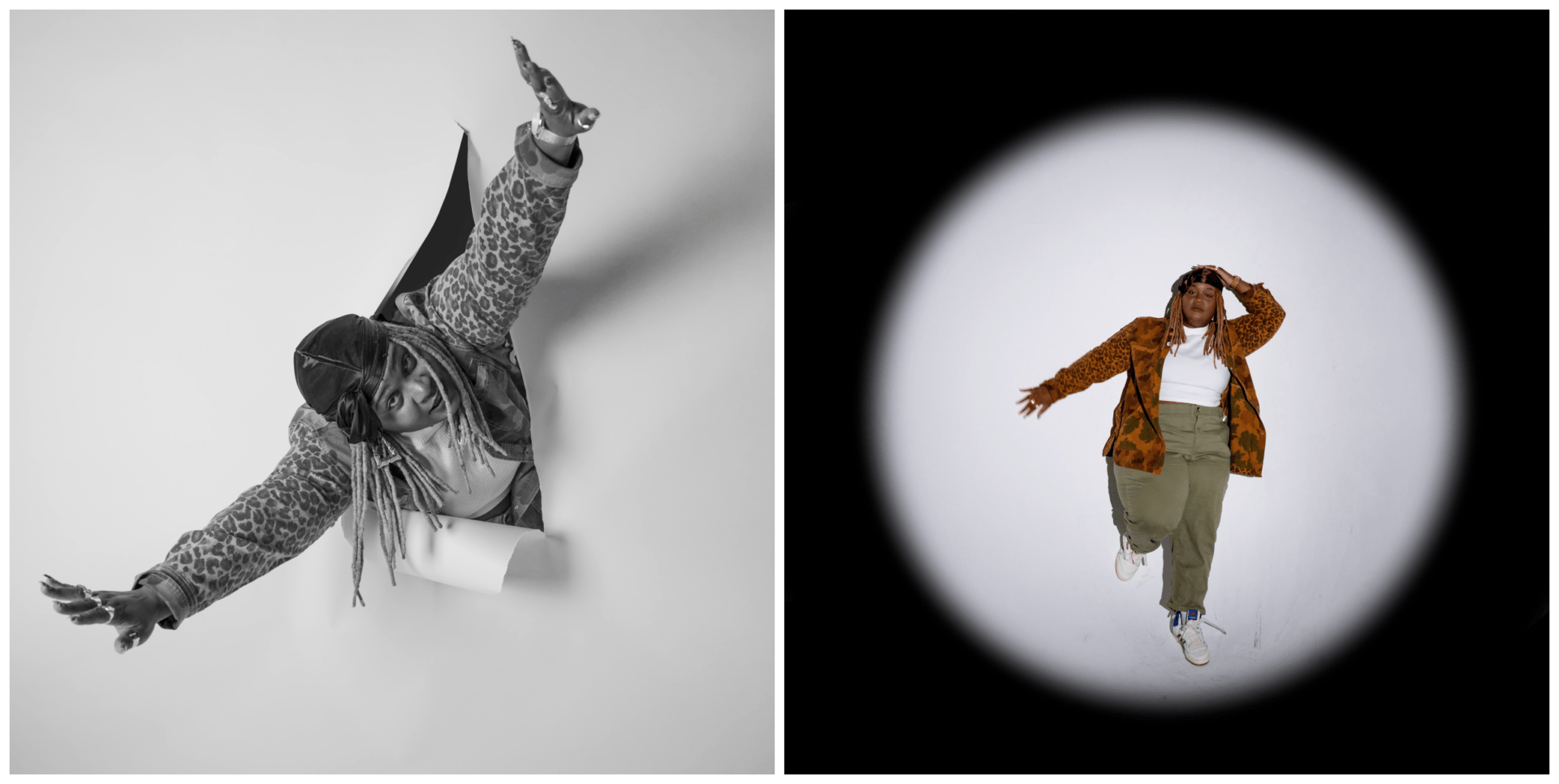

Oompa

Over the last year-and-a-half, many artists have been left with one option: pivot. Whatever plans were set in stone pre-pandemic disappeared. Oompa’s plan was to move to New York City. Instead, she came home to herself. The Boston-based rapper immersed herself in her music, which has resulted in a new album called “Unbothered,” to be debuted at the Paradise Rock Club in Boston on Oct. 8.

“I just took the chance and was like, ‘I'm going to have fun making a project,’” Oompa says. “I'm not worried about being a better rapper. I'm not worried about the narrative people want. I'm not worried about any of that. I am just having fun and just chasing joy.”

She says a lot of this album is freestyle. It came out piecemeal, bit by bit. She defines being “unbothered” as being tired of fighting, and simply not keeping record of things that want to kill her anymore. She’s explored her demons in music and therapy. This is the byproduct of that work — a joyful exploration of the present moment.

“The thing that I'm most excited about is the thing that I've wanted for years, which is a team of people who love me as much as I love them and who see the vision, or at least believe in it, and who are trying to make the art that I want to make as well,” Oompa says. “And we’re finding a way to support each other. So that's been really dope.”

Pascale Florestal

Looking back, Pascale Florestal knows her younger self would look at her wide-eyed if she could see everything she has accomplished. Now a director, educator, writer and collaborator, the Boston-based Florestal is seeking to diversify representation onstage, one play at a time. She’s working on several shows this fall for theaters across the commonwealth: ArtsEmerson, the Boston Conservatory at Berklee, the SpeakEasy Stage Company and The Umbrella Arts Center in Concord, Massachusetts. The Front Porch Arts Collective, where Florestal serves as the education director, just announced a three-year residency at the Huntington Theatre Company.

“So often I feel like I'm at this precipice of getting to the point of where I can name myself as an artist, claim it and be secure in that title,” she says. “I think that's finally where I am. I think I've been waiting a good seven, eight years. I moved here to Boston in 2014 and now, at this moment, I feel as though I can say I'm an artist and I'm making that more than just my career, but my passion work.”

One of her proudest moments was serving as dramaturg for “Pass Over,” by Antoinette Nwandu, and being able to bring the actors into a juvenile center in Boston. She believed it was important that the center's young people see what was possible, see themselves in the Black actors and actors of color.

“It was just such a beautiful moment to see how art can connect with young people in so many ways and how the art can also change the landscape in which we work that is so restrictive of Black stories on the stage,” she says.

In them, she sees her younger self, the little girl who never imagined she’d survive as an artist. “I never knew anyone who could do that work and be happy and make money and be able to live. To see myself doing it now is insane. It's unreal. I still don't believe it. Every day I have to remind myself that I am doing what I've always wanted to do.”

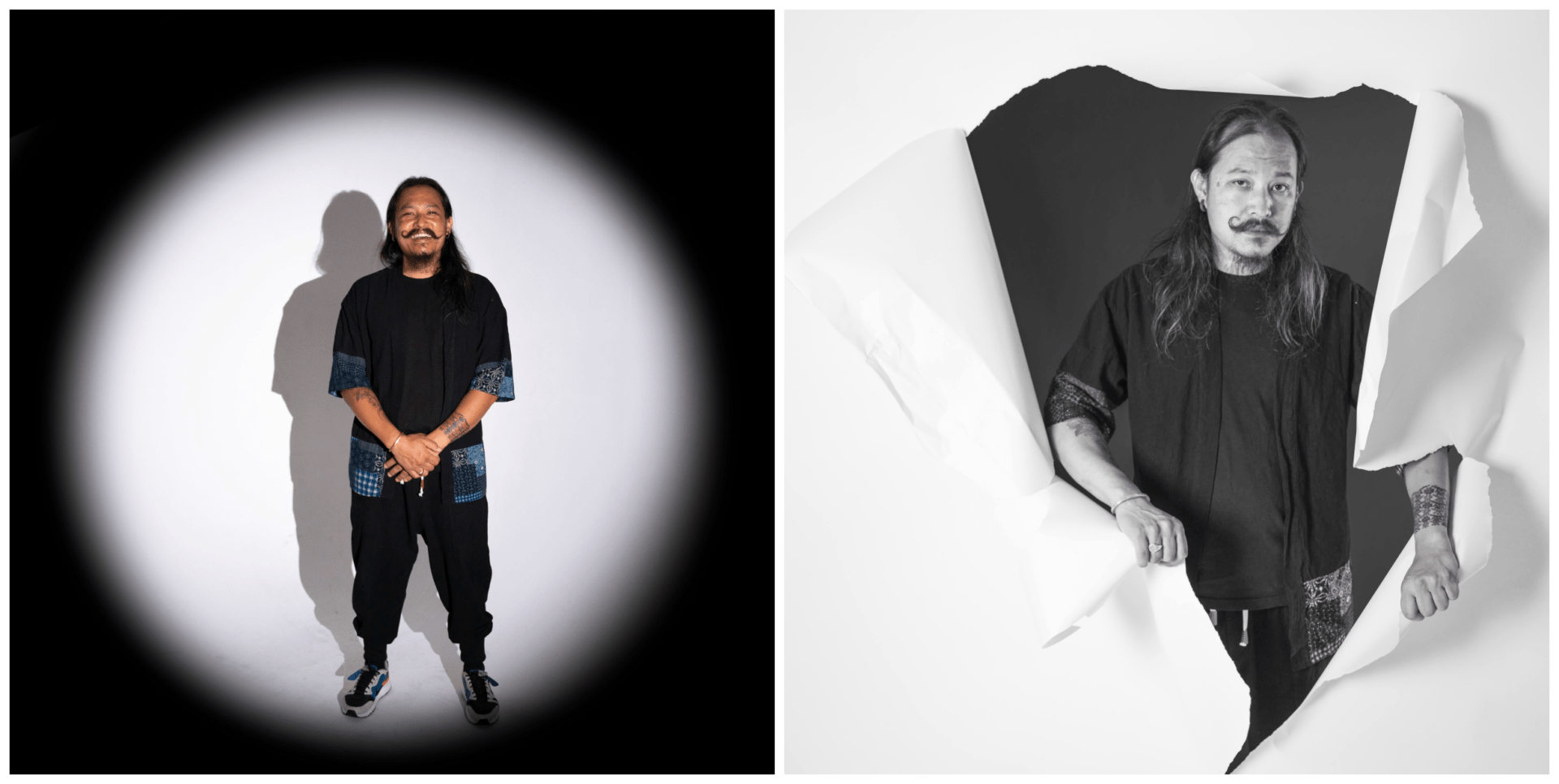

Philip Keith

Philip Keith almost quit photography. It was 2019, and he was struggling to break into the Boston photography scene after spending two prolific years in the Berlin fashion industry. The onset of the pandemic stranded him at home, at loose ends. Then, unexpectedly, the movement for Black lives brought him out again. “I wanted to go out and use my camera,” Keith says. “I did find that I sort of had an eye for it.” An image he took at the first major Boston protest, of a demonstrator’s fist silhouetted against a starless sky, landed on the cover of Bloomberg Businessweek. That led to more cover assignments: Cornel West, Ayanna Pressley, John Kerry. Suddenly, he had more work than he knew what to do with.

Though protest photography jump-started his career, Keith doesn’t want to be defined by his images of Black Lives Matter demonstrations. “I seek to have my work encompass more of the Black experience — or more just the human experience,” he says. “I don’t want it to be focused just on this moment of struggle.” He still loves to take portraits. This summer, he started work on a personal project photographing the Inkwell, a historically Black beach on Martha’s Vineyard. It’s a spot that’s been photographed many times before. Keith wants his images to show something different — to get at the history of the place, to reveal depths that aren’t immediately visible. “You’re seeing the thing that’s photographed, and you begin to have a conversation with that,” he says. “But there’s a lot more about the story.”

Rayna Yun Chou

As a classically-trained violist, Rayna Yun Chou always had an urge to do something more — on and off-stage. She remembers wondering, “Can I create middle grounds where people of all backgrounds can simply encounter and experience music in new ways?”

Chou answered that question in 2019 with a public project called “Concert for One.” In collaboration with Celebrity Series of Boston, she organized a series of nano-sized pop-up concerts inside shipping containers set up on Harvard's Science Center Plaza and in Chinatown. The tiny, temporary performance halls held one musician who played one minute of music for one audience member.

“I worked with 60 local musicians and performed for over 4,000 listeners in the extremely intimate, one-on-one, face-to-face setting,” Chou recalls. “It was a project that proved musicians of different genres and listeners of different backgrounds were open enough to new and unknown experiences.”

It also showed the New England Conservatory grad that it was possible to reshape the classical performer-audience dynamic. Chou believes music is universal, and concerts are inclusive. “I have witnessed the power an art project has in public on an unsuspecting public,” she says. “I think it is beautiful to create art that becomes a part of life.”

Chou, now 28, premiered her second large-scale social experimental work last year in her homeland of Taiwan (as she did “Concert for One”) when live events were still permitted. “Hear the Light” was an immersive installation inside an old factory that had been converted into exhibition spaces. Participants entered a darkened tunnel, then followed the sound of music to find their way into a light-drenched garden filled with grasses, flowers and live music.

Chou's goal was to give people hope and healing through music in enduring dark times. She believes it worked, and one day wants to recreate “Hear the Light” in Boston.

Red Shaydez

Red Shaydez is one of those people who can always identify the sample in a hip-hop beat. It comes from a childhood saturated in music: her mother’s vast album collection, her father’s ‘90s hip-hop group. “Music has just always been a part of me,” she says.

Shaydez started building a fanbase online when she was still a teenager. She developed a precise, emphatic rapping style shaped by the duality of her childhood: the school year spent in Boston, summers spent with family in Georgia. “Lyrically, I’m definitely influenced by the East Coast,” she says, though her tastes are colored by the South. “I love my drums to hit hard, and I love a particular BPM [beats-per-minute] during my beat.”

In an era of trap beats and minimalist sing-rapping, Shaydez has always seemed like a bit of a throwback. But her 2020 album, “Feel the Aura,” broke new terrain. The production is contemporary, but subtly so; Shaydez demonstrates a newfound facility for hooks without softening her lyrical virtuosity. More importantly, she expresses herself with fresh candor. “I felt like I was breaking free, and I was finally able to put on the table all the facets of who Red Shaydez is,” she says. “I’m demi-sexual/ Then I was sapio,” Shaydez raps on the song “They Call Me Shaydez” — a take-it-or-leave-it embrace of the necessity of evolution.

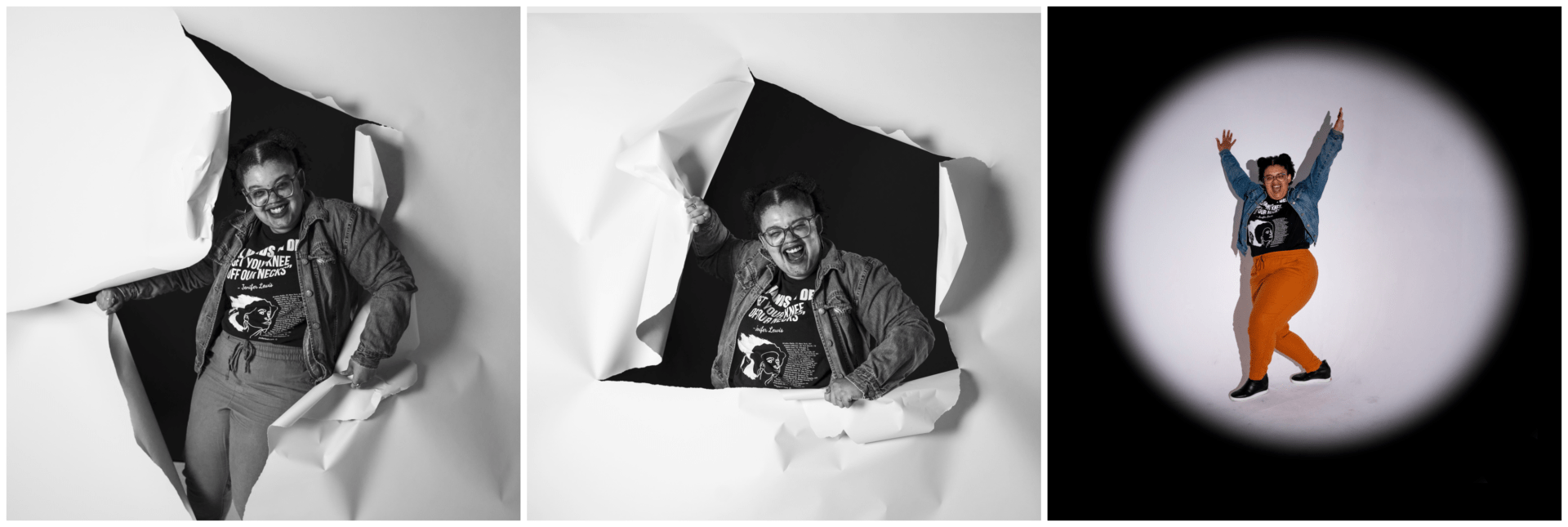

Tonasia Jones

Tonasia Jones started her career as a student in the acting program at Emerson College, but says she realized early on she wasn’t a “capital-A actor.”

“There were rooms that I went into that were not set up for me to succeed in,” she says. She knew she wanted to be an agent of change in the industry, so she stepped into administrative roles and eventually added producer and director to her resume.

Her work as both an administrator and creator has been sought after by top institutions throughout the Boston area, such as the American Repertory Theater, ArtsEmerson, Huntington Theatre Company, The Theater Offensive, StageSource and SpeakEasy Stage Company, among others.

Her success in each role is informed by her love of acting and her desire to support other performers who’ve been marginalized, misunderstood, abused and excluded. As a contractor wearing many hats, she stresses the importance of clear boundaries in each job to keep work sustainable.

“There can be a lack of transparency in roles, but I put my boundary up and say what needs to be done,” says Jones. “If I’m the director, it’s not my job to write the systems, that’s the producer’s job. It’s also not my job to change your theater when I’m only hired as a temporary contractor.”

Jones says that while the pandemic has been difficult for the performing arts sector, it's also offered space and breath to make change. “I could ask questions about the systems in place. People were like, ‘Well, that's the way it's always been done.’ But there is white supremacy in this answer. Just because something was done the way it's always been done doesn't mean we need to continue enacting it.”

Audiences can catch Jones’ directing work this fall in “BLKS” at SpeakEasy Stage. She’s also excited to launch her new residency with The Theater Offensive called Queer (Re)public for queer and trans artists of color, which aims to break down the hierarchical structures in Boston’s arts ecosystem.

“These white supremacist ideas about ‘excellence’ and ‘perfection’ are not art,” says Jones. “They are actually the antithesis of art.”

Woomin Kim

“The xenophobia in the last year-and-a-half, while not new, is heightened,” says Woomin Kim, a Boston/New York-based Korean artist who makes sculptures out of everyday objects. That xenophobia coupled with the limitations of the pandemic inspired her latest ongoing project: fabric murals of Korea’s shijang, or open marketplaces.

“There was an idea that diseases are born in street markets, and then I started recognizing in Hollywood movies that Asian markets are dark places where something mysterious is happening, and they were one of the first places to shut down because of COVID-19,” says Kim. “But they are a way of life for so many people. I used to go to the markets all the time and love the vibrancy and assemblage of everything you can get there.”

She wanted to show the shijang experience in a celebratory way, and chose to work with fabric, both because it recalled the textiles sold at the markets and the colorful banners beckoning shoppers, and it was easy to work with at her small desk space. She says fabric is easily accessible and evokes memory for everyone, while offering countless possibilities in terms of color, pattern and texture, making it the perfect medium to express the vibrancy of these open air markets.

Kim moved to the United States to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and afterward moved to Boston with her partner in 2016. She says that even before the pandemic hit, lack of space was a major obstacle for Boston artists.

“When I was in Chicago, it was just cheaper for artists to experiment, and a lot of spaces were available and there was this potential that anything can happen,” says Kim. “That is just not possible in Boston.”

Because of this, she thinks there’s a false sense outside the region that Boston is devoid of artists. “There are so many young, talented artists here, and the ongoing assignment is to find each other and make things happen without the help of huge gigantic institutions or funding sources, because Boston can be expensive and spaces can be not totally welcoming to the artists.”

Yara Liceaga-Rojas

A piece of the land that Yara Liceaga-Rojas grew up on, that beach in Puerto Rico, sits within her always. The movement of the waves. The expansiveness of the ocean. A queer Afro-Caribbean Puerto Rican mother, poet/writer, performer, cultural manager and educator, Liceaga-Rojas describes her art projects as revolving “around the visibility of marginalized subjects.” In recent months, she nurtured other artists — an advocate, mentor and consultant who helped so many bring their visions to life.

“I was battling with imagination during the pandemic,” Liceaga-Rojas says, “...but then my own work fell on the side. I'm also doing my master's degree in cultural administration. So that takes a lot of space.”

As an artist, she’s always said her weakness is the analysis of human relationships, those bonds that bring joy and the occasional misunderstanding. She interrogated these connections through her program “Poetry Is Busy” and, very early in the pandemic, through the Cloud Cafe, a virtual performance that brought artists together on Zoom.

Now, she’s ready to return to her own practice and what’s been building inside her, which is a desire to dance. Something in her body misses movement, though she has no training as a dancer. She imagines herself onstage, experimenting with a new medium and honoring her late mother in the process.

“My mom wanted to dance really badly,” she says. “She wanted my dad to take her to dance. That never happened. And so I kind of stayed with that... unfinished business.”

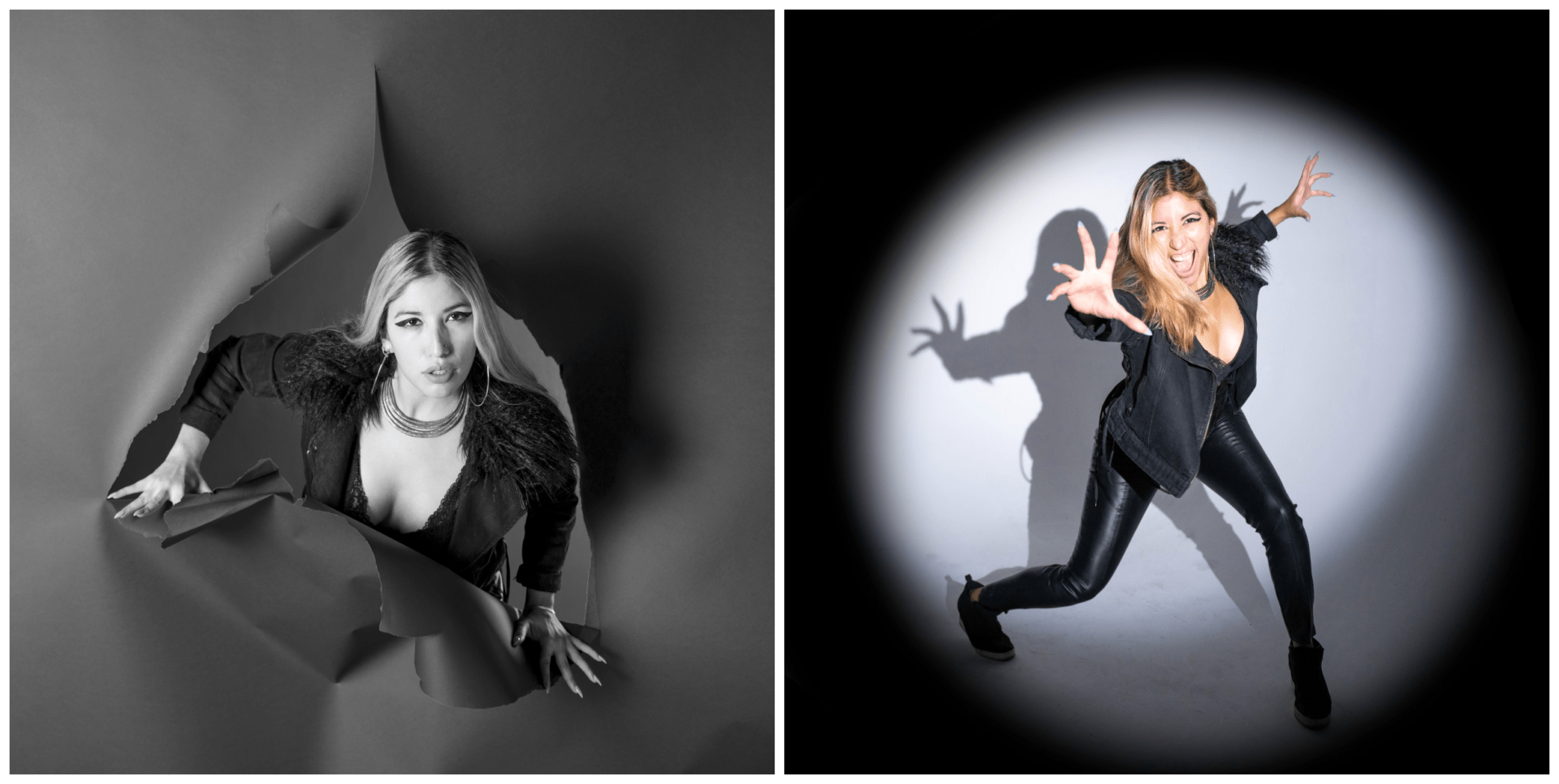

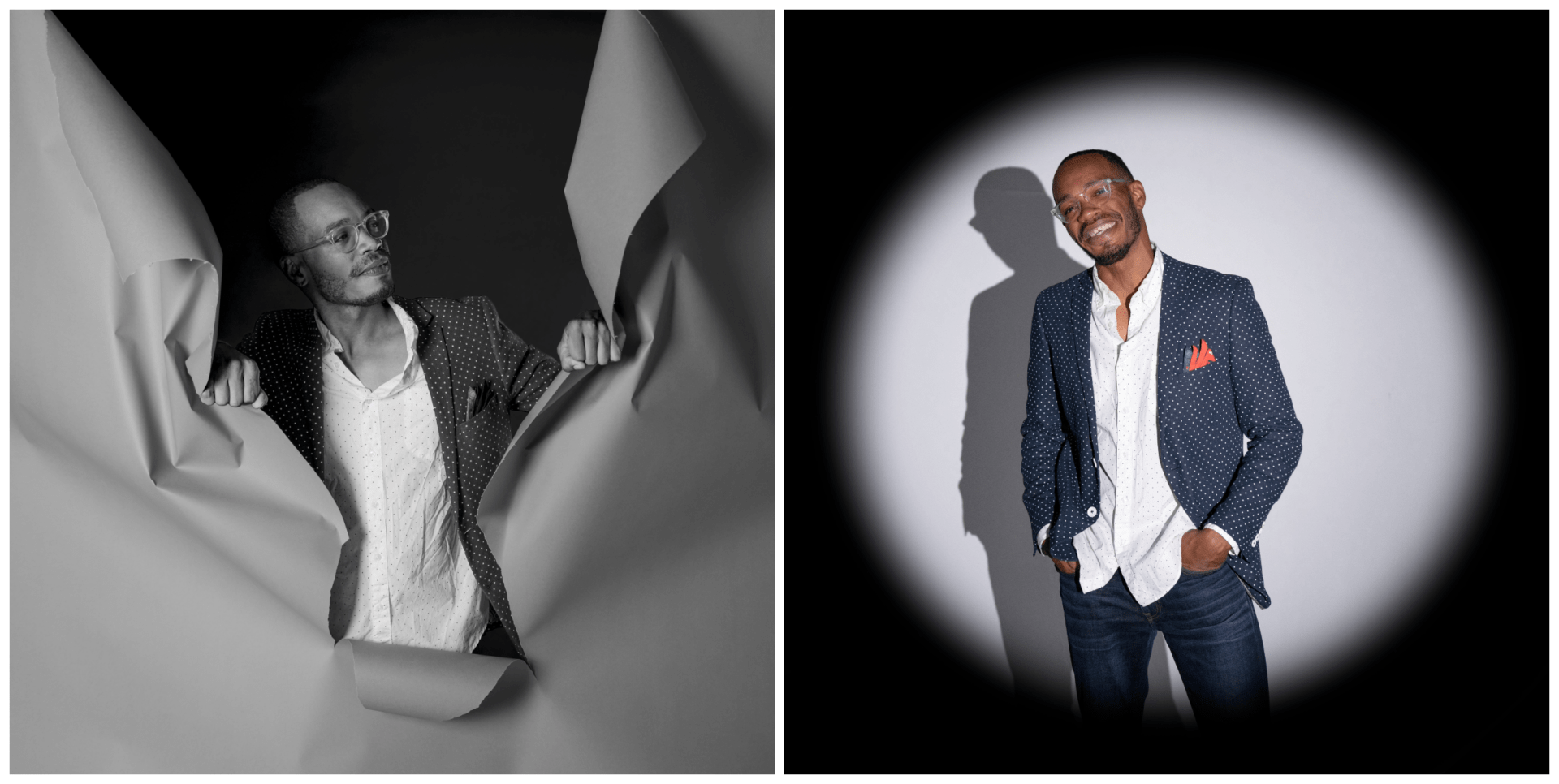

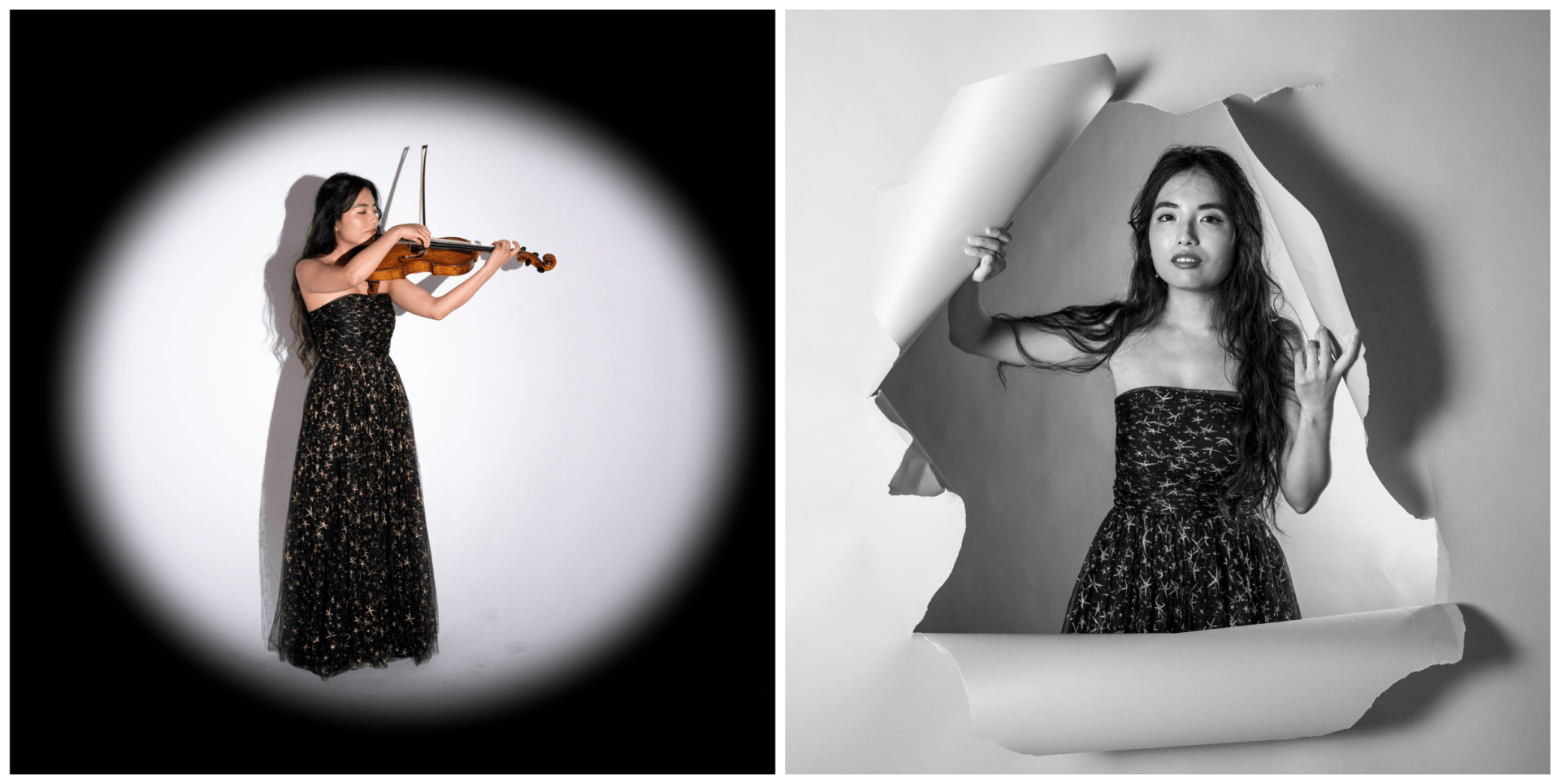

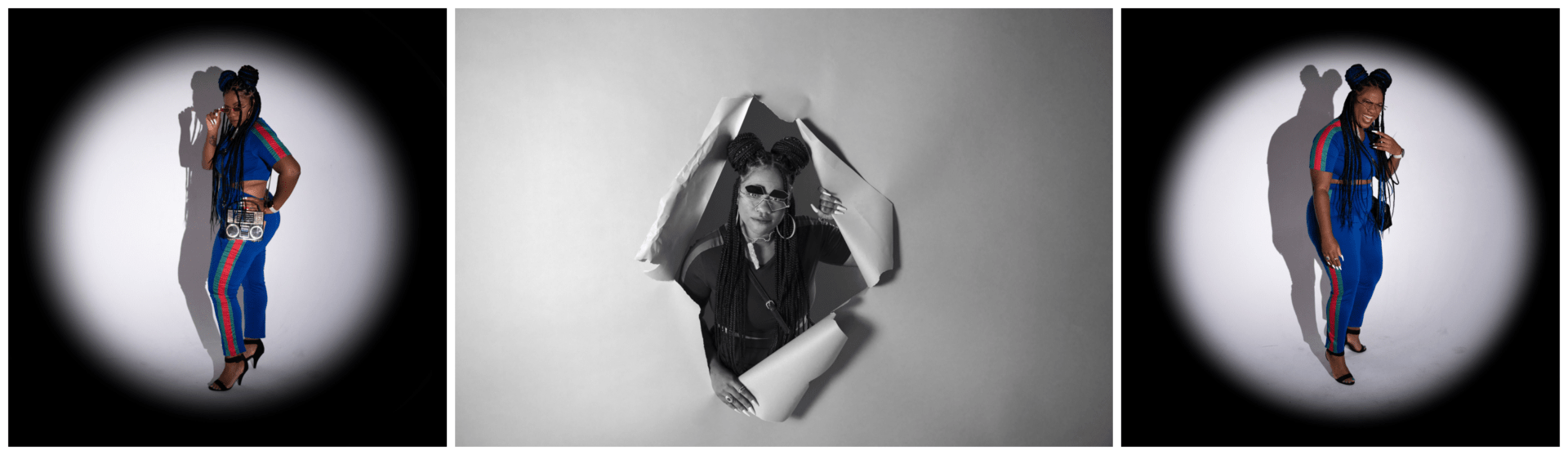

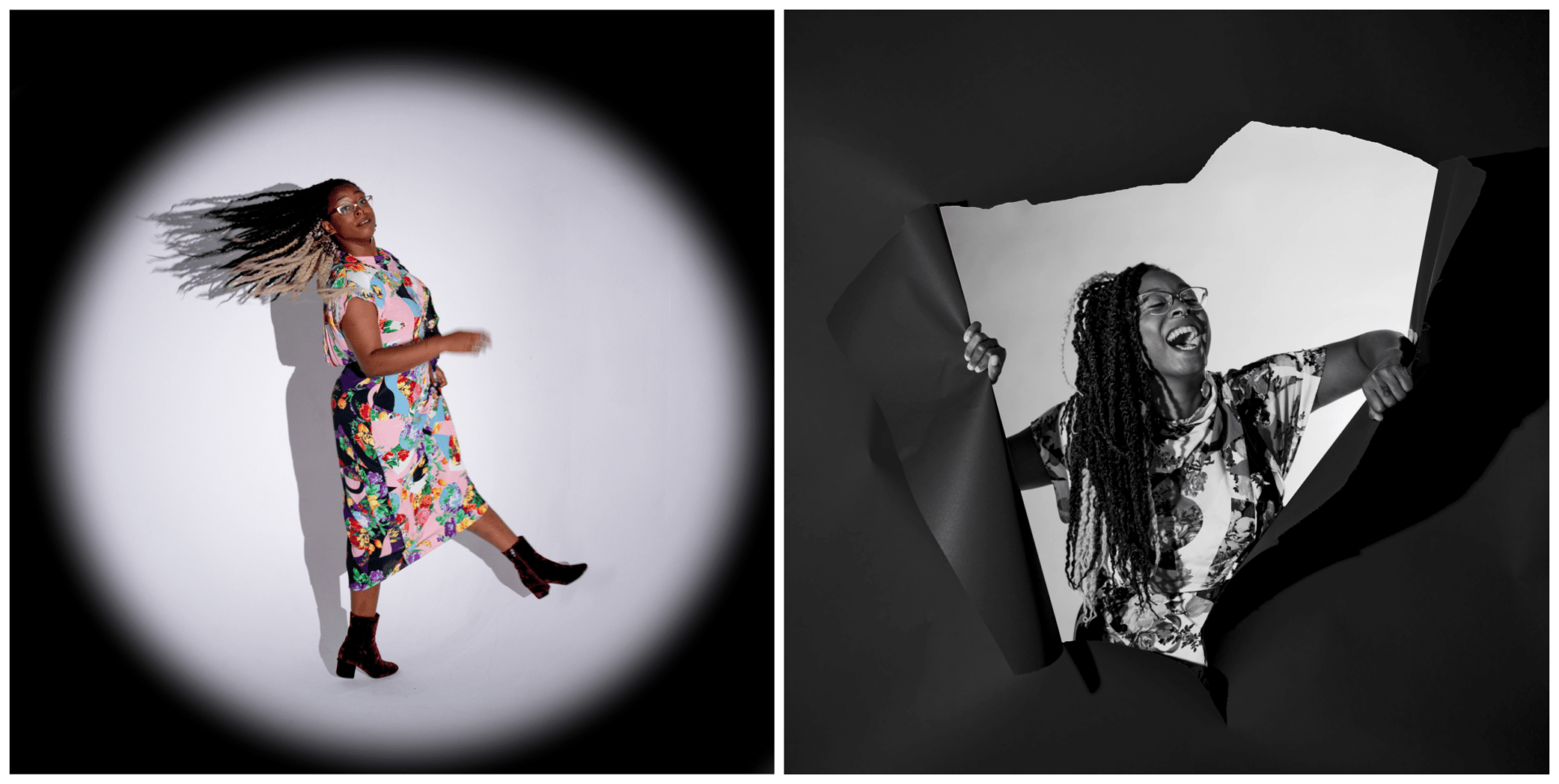

Photographer OJ Slaughter captured the images for The ARTery 25 and Alberto Montalvo filmed the video for the series.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated Pascale Florestal's role in production of "Pass Over." She served as dramaturg, not director.