Advertisement

Commentary

Harvard Film Archive highlights an unsung Taiwanese filmmaker

The Harvard Film Archive has been closed to the public since March of 2020. In keeping with the university’s COVID-19 protocols, there have been a few stray screenings restricted to students and faculty, while the rest of us without Harvard IDs have dearly missed the eclectic and adventurous programming at this hidden-away hub for the community’s most hardcore cinephiles. I was actually at the HFA the night the school — and the world — shut down, when a visibly rattled Kelly Reichardt introduced the final screening in a retrospective of her films by saying, “Welcome to the last picture show.” (Little did I know that night, I wouldn’t be back in a movie theater for 14 months.)

So many of my favorite filmgoing experiences happened in that little underground cinema on Quincy Street in Cambridge. I could tell you stories about seeing heroes like Kathryn Bigelow, Pam Grier and Sofia Coppola there, as well as multiple memorable evenings with the legendary — and legendarily boisterous — William Friedkin. But the archive wasn’t just a place for famous favorites. In fact, the programmers prided themselves on introducing new talent with whom you might not yet be familiar. HFA retrospectives were how I discovered the films of Angela Schanelec, and I’m still kicking myself for skipping the Sunday afternoon six years ago when an up-and-coming director named Ryûsuke Hamaguchi brought his new five-hour film called “Happy Hour.”

The mission continues, online anyway, at the Harvard Film Archive Virtual Cinematheque. “Tabooed Initiation: Two Films by Mou Tun-Fei” is a new streaming series curated and coordinated by Harvard University’s East Asian Film & Media Working Group, presenting a pair of impossible-to-find pictures by an unsung groundbreaker of Taiwanese cinema. In an attempt to replicate the HFA experience at home, the films are accompanied by lectures from Victor Fan of King’s College London and Wood Lin from the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute. Even better, the program is free to the public.

Familiar to those whose cinematic tastes tend to the extreme, Mou Tun-Fei was known as a sexploitation filmmaker in 1980s Taiwan. In one of the lectures, Wood uses the word “monster” to describe his reputation in the industry. Indeed, a perusal of the non-pornographic titles in Mou’s later filmography includes the notorious 1980 “Lost Souls” — a remake of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s pulverizing “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom” transplanted to Hong Kong — as well as the grisly “Men Behind the Sun” films chronicling Japanese war crimes and something called “Trilogy of Lust.”

But the early films presented here in the HFA series betray little of the bitter gorehound Mou would become. 1969’s “I Didn’t Dare Tell You” and 1970’s “The End of the Track” are gentle, humanist portraits of young people struggling to get by in an uneasy time of economic inequality, reminiscent of the Italian neorealists in their devotion to everyday life. Both films ran afoul of what Fan explains was Chiang Kai-shek’s “Healthy and Clean Initiative,” as depicting the realities of poverty was considered bad for the nation state’s morale. “I Didn’t Dare Tell You” had a happier epilogue slapped onto the end, while “The End of the Track” was banned outright, as the intense friendship between its teenage male protagonists was deemed too homoerotic for “healthy and clean” audiences.

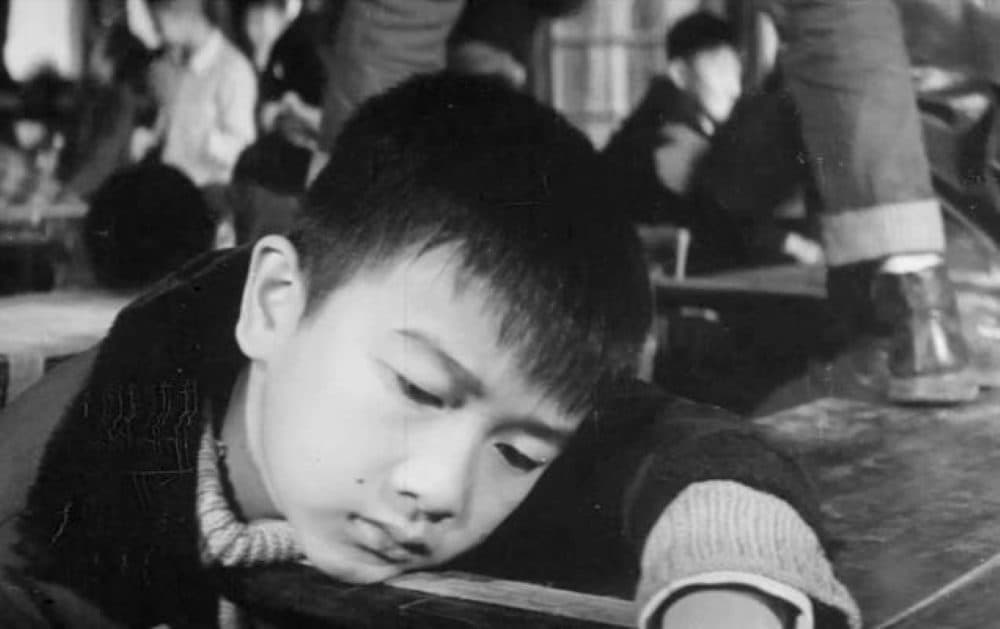

“I Didn’t Dare Tell You” is the story of Dah Yuan, a sensitive young boy being raised by a degenerate single dad who owes thousands in gambling debts. The kid’s got a crush on his stern schoolteacher, who on the advice of her longhaired, bearded artist boyfriend (played by the director himself) decides to ditch the glasses and literally let her hair down, taking a more openly emotional interest in the lives of her students. (He makes a big show of smashing her spectacles, which she didn’t need but was wearing because they made her look meaner.)

Advertisement

Hoping to bail out his deadbeat dad, Dah Yuan sneaks out at night to work a secret job, which of course leads to him screwing up at school and prompting his teacher to take notice. The plot gets a little bumpy here, as the Taiwan Film Institute’s restoration comes from the only existing 35 mm print of the picture, which is unfortunately missing the eighth reel. But you can figure out the gist of things quickly enough — it felt like coming back after a trip to the bathroom at the movies — and the overall arc of the story remains uninterrupted.

It’s an enormously sensitive portrayal, shot in beautiful black-and-white. Mou crams the widescreen compositions with life and energy, cleverly positioning planes of action to give great depth to every frame. Interestingly, he adopts the exact opposite approach in the following year’s “The End of the Track,” which is so sparsely shot it’s constantly isolating the characters off by themselves, surrounded by nothing. The chatty soundscape of “I Didn’t Dare Tell You” is replaced here by a minimal dialogue and hushed silences, a sense of being all alone in the world.

That’s how young Hsiao Tung feels after the sudden death of his best friend Yung Shen from a heart condition — he dropped dead on the racetrack while they were running laps. The boys were inseparable despite coming from deeply dissimilar classes. (The relationship reminded me of the rich kid/poor friend dynamic in “Y Tu Mamá También,” and these two spend just as much time skinny-dipping and inspecting each other’s private parts.) Plagued by survivor’s guilt, Hsiao Tung attempts to replace the deceased boy at his parents’ food cart, wearing the dead kid’s clothes and tirelessly working menial labor to try and make up for the fact that he’s alive and his friend is not.

Work is the common refrain running through these two pictures: the performance of unrewarding tasks, whether to rescue our loved ones or give meaning to their absence. It’s not exactly a surprise that such searching, skeptical films would irritate a nationalist regime. What’s puzzling is how the director of two films so compassionate and delicately attuned to the human condition could spend the rest of his career as a pornographer and purveyor of ghastly, despairing images. Without delving too far into armchair psychoanalysis, one could imagine Mou’s sensitivity to the inequities so unsparingly depicted in his films ultimately curdling into rage. I suppose you can only see kindness trampled upon for so long before you feel like remaking “Salò.”

“Tabooed Initiation: Two Films by Mou Tun-Fei” is available to stream for free at the Harvard Film Archive Virtual Cinematheque through Sunday, Jan. 30.