Advertisement

Urban forests may store more carbon than we thought, study finds

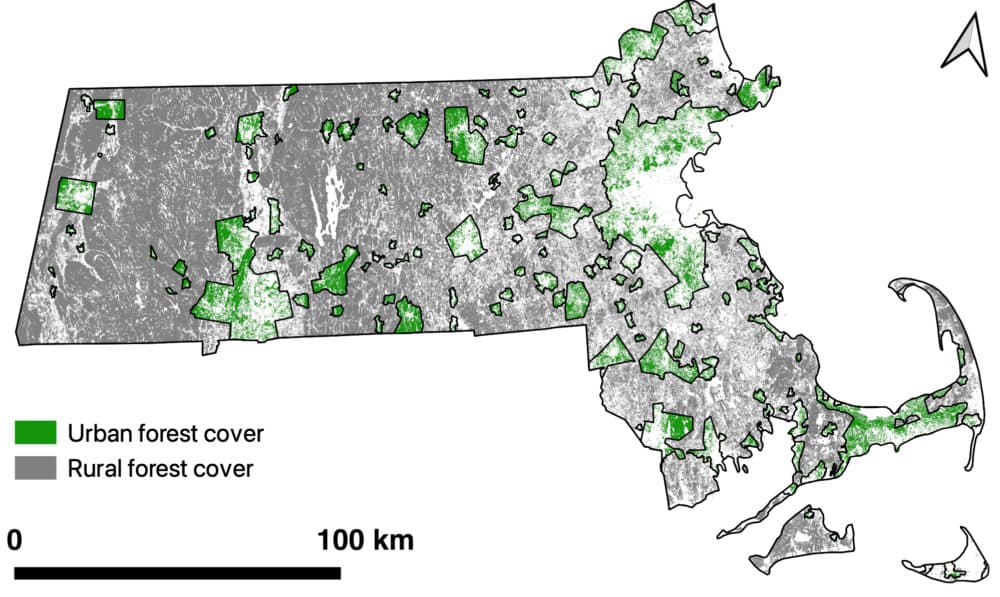

Urban forests are little oases of nature, but they don't get a lot of respect. The trees near the road get sprayed with salt and choked with soot; the boulders get tagged with graffiti, the trails through the woods are often littered with candy wrappers, soda bottles and plastic sacks of dog poo.

But despite the abuse, these small patches of forest may play an outsized role in combatting climate change, at least here in the Northeast. Two studies from Boston University find that trees around the edges of urban forests grow faster, and the soil gives off less carbon dioxide, than scientists expected. That means these scruffy edges are surprisingly good at pulling carbon dioxide out of the sky, and storing it underground.

The research suggests that fragmented urban forests, often dismissed as degraded remnants of their former selves, maybe be doing more for us city dwellers than we thought.

"The discussion about deforestation really focuses on what's lost: the forest that's lost, the habitat that's lost. But we haven't focused enough energy on what's left behind," said Lucy Hutyra, a professor of earth and environment at Boston University, and senior author on the two studies. "These forests, even these crummy little trash-filled urban forests with few trees, do a lot for society."

Humans have chopped up most of the world's forests into smallish "fragments," bordered by roads, houses, factories and shopping malls. Although there's no formal definition of a forest fragment, a good working definition may be a patch of woods where you can always hear the traffic, even if you can't see it.

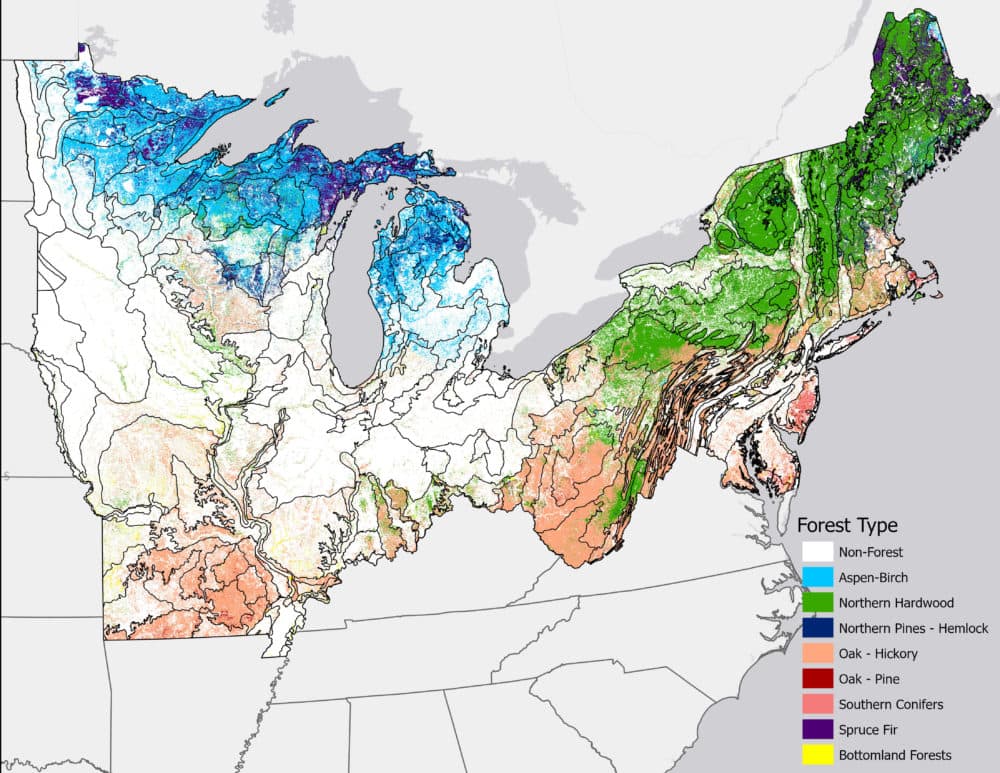

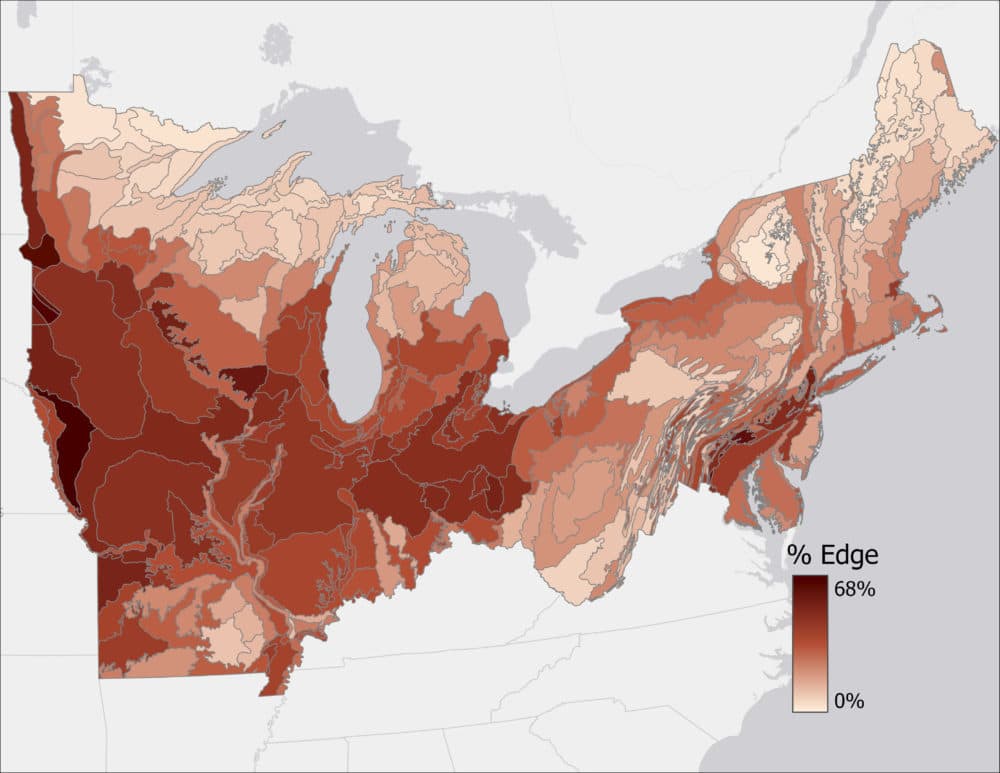

In the Northeastern United States, there's a lot of urban woods like this: almost a quarter of the forest in the region sits 100 feet from a forest edge. And there are more fragments by the day: Massachusetts alone is losing about 5,000 acres of forest each year, according to Mass Audubon.

Research on tropical forests has found that trees along these edges, exposed to more wind and heat, tend to dry out and die more quickly than their cousins tucked safely inside. A team of researchers working under Hutyra wanted to find out if the same were true for the forests around here. The answer: nope.

The team's first study, published in Nature Communications, found that trees around the edges of Northeastern forests were no more likely to die than trees in the interior — in fact, they grew 36% faster faster and 24% thicker. The trees probably did so well because they had enough water, more access to light and actually liked sucking up all that carbon dioxide from neighboring roads and buildings.

"Pollution is a good and a bad thing from a plant's perspective," said Hutyra. "Some of that pollution is definitely not what the forest would want, but some of it is carbon dioxide, which will stimulate growth, and some of it is reactive nitrogen, which serves as a fertilizer."

A separate study published Wednesday in Global Change Biology found that the soil around these urban forest edges emitted carbon dioxide 25% slower than soil deeper in the woods. Even weirder, the emissions slowed down when it got hotter, which did not happen in more rural regions. In other words, the soil near the edge of urban forests seems to be doing some turbo-charged carbon storage, and nobody is quite sure why.

Study author Sarah Garvey, a Ph.D. candidate at Boston University, said the result is both "exciting" and "perplexing."

"Urban soils are experiencing really high temperatures. And so we would expect, if it's really hot, that they would respire more. But that doesn't seem to be the case," she said.

Even without understanding the nuts and bolts of what's happening, the finding is still noteworthy. Because humans are scrambling for ways to pull more climate-warming carbon dioxide out of the sky, the combined findings of these studies could have have broad implications for both climate policy modeling.

"Forests are increasingly fragmented. You have more edge area and this is a general pattern across the world," said Luca Morreale, author of the Nature Communications study and a Ph.D. candidate at Boston University. "If you view edges as degraded and 'lesser-than,' then you will perhaps not care as much." But if climate modelers and policymakers take that view, he said, it "could very drastically affect our world's forests."

These results don't mean we should start chopping up forests to create more powerful carbon sinks; that's a losing proposition, said Hutyra. But having chopped up the forests already, it's important for us to understand the consequences.

"We are making decisions about how to design and redesign our cities towards a goal of sustainability, and vegetation is a big part of that," Hutyra said. "Whether it be conversations about planting trees all over the world to mitigate climate, or about New York City or Boston schools increasing canopy cover to mitigate summer excess heat, this science is feeding into that."