State commission takes years to resolve discrimination cases. One took 17. Another took 15

Michelle Pavlov was seven months pregnant when she got fired. The owners of Happy Flooring in Yarmouth said they were closing their showroom on Cape Cod and couldn't afford to keep her on as a manager.

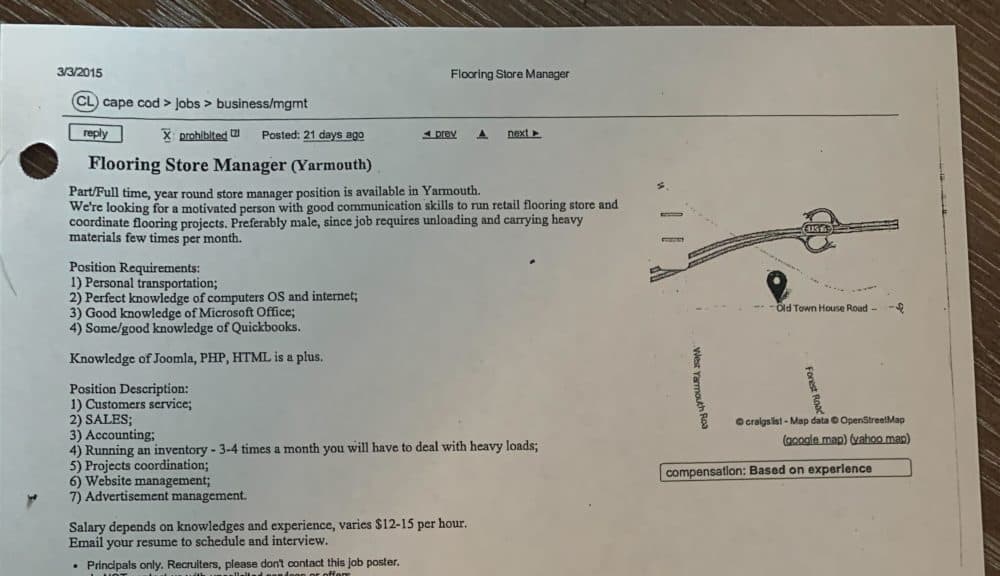

But when Pavlov started searching for a new job online, she came across a Craigslist ad for what looked like her old position — with one key difference: The post said candidates should be "preferably male."

Pavlov immediately filed a gender bias complaint with the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination. Then, she waited. And waited.

That was seven years ago.

She finally got a ruling in her favor this spring, but the company told her it plans to appeal, which means the case could drag on for several more years.

Meanwhile Pavlov’s son — who wasn't even born when she was fired — is now in first grade.

"He's seven," she said. "He shouldn't have to know about commission counsels and discrimination.”

More and more people like Pavlov have been stuck waiting years for the MCAD to make rulings. The agency has long had a reputation for tardiness, but the pandemic has made delays far worse as the agency lost employees who were not replaced.

The backlog of old cases under investigation for more than 18 months has climbed more than five-fold since 2019, the agency’s own data shows, reaching 1,400 cases today. And many cases take much, much longer.

The MCAD took 17 years before last year dismissing a retaliation complaint by a fired electrical grid worker. A gender discrimination case against the Massachusetts Port Authority lasted 15 years before it was withdrawn in 2021. And records show that a dozen current cases have been pending for more than a decade.

"I feel like the system is broken," said Mela Bush-Miles, a community organizer based in Roxbury. She said the long wait times suggest that fighting discrimination is a low priority in Massachusetts.

Some advocates also fear the delays could deter many victims from coming forward at all, missing the chance to catch violations and hold institutions accountable.

"People are just going to give up," said Tom Murphy, supervising attorney with the Boston-based Disability Law Center. And Murphy worried that could encourage people in power to just ignore the rules designed to stop discrimination.

A mounting backlog

MCAD spokesperson H Harrison acknowledged some cases have taken years to resolve. But he insists the commission was working its way through the list of backlogged complaints before the pandemic.

"We were arm's reach from being able to eliminate the backlog," he said.

But after COVID started spreading in the United States, Harrison said the agency suffered a number of setbacks. It had to cut back on interns, who often help with investigations. Many key employees resigned, including MCAD's general counsel and all three hearing officers. And the agency had to temporarily impose a hiring freeze early in the pandemic after losing roughly $380,000 in federal funding.

That shortfall was later replaced by the state, but the staffing woes remain. The MCAD says one-quarter of its 33 investigative slots still need to be filled.

Those who remain at the commission are often overwhelmed. MCAD investigators — who conduct interviews and determine whether there is enough evidence to show there was likely a violation — are now assigned an average of 150 to 200 cases each, compared to just 30 cases a piece at Connecticut’s anti-discrimination office.

“It’s incredibly stressful,” said one person who recently left the MCAD’s investigations unit and asked not to be named because they might want to work for the commission in the future.

In part because of the growing delays, several attorneys said they now prefer to pursue discrimination claims in civil court instead.

But advocates say many people who can't afford an attorney depend on the commission to handle their cases. And some noted the commission is also a better venue for many discrimination cases that hinge on evidence generally not allowed in traditional courtroom proceedings, such as an employee recalling what their boss told them in private.

“In many of these cases there are no witnesses," said Susan Howards, of Brookline, a criminal defense attorney who represents people at the MCAD. "It's between you and your supervisor or you and somebody in school."

But Howards warns clients it can sometimes take more than a decade to resolve a case at the MCAD. "They're shocked," she said.

The stress of waiting

Even filing a case at the MCAD has become more difficult lately. The agency says it now takes three months just to get a meeting to lodge a complaint with a staffer — something people could once do anytime at an MCAD office in Boston, Springfield or Worcester.

Then it takes an average of two more years to get a preliminary decision on whether there is enough evidence to pursue a claim. A final ruling can take many more years.

Among the six cases the full commission decided last year, the average wait was 10 years. That's more than double the average wait for the four decisions by the full commission in 2010 and 2011.

One of the long-delayed cases decided last year was brought by Rigaubert Aime, a Black retired corrections officer from Mattapan. He filed a discrimination claim in 2011 against the state prison system, claiming superiors retaliated against him for alleging racism.

An MCAD staffer initially dismissed the case after five years. Aime appealed. And then it took another five years for the full commission to uphold that decision.

Aime said that stress of waiting for an MCAD decision all those years took a toll on his friendships. And once a bodybuilder, he stopped going to the gym entirely.

Aime, now 52, said there’s no way he could recommend going to the MCAD for help:

"The waiting time, it's going to take a toll on you," he said. "It's going to be worse than what you actually are going through at your job."

"The waiting time, it's going to take a toll on you. It's going to be worse than what you actually are going through at your job."

Rigaubert Aime

In Barnstable, Pavlov sat at her dining room table, leafing through a three-ring binder bulging with every remnant of her job at Happy Flooring.

"They hired me to do everything," she said, "from some marketing to running their showroom, supplies, I mean, the whole shebang."

For a while, things seemed to be going well.

Pavlov’s personal life was going well, too — she got married, bought a house with her husband and soon had a baby on the way. As her family's sole breadwinner at the time, she thought she’d go briefly on maternity leave before returning to work.

But later into her pregnancy, after she recalled asking for help lifting heavy buckets of materials at work, the company let her go in February 2015.

The company, now called New Flooring, didn't respond to requests for comment. But at an MCAD hearing, the company denied it fired Pavlov because she was pregnant.

Former owner Siarhei Huba testified that he made a mistake in writing "preferably male" in the Craigslist ad listing Pavlov's old job. "I didn't mean to offend or discriminate [against] anybody. I just wanted to explain the job requires heavy lifting," he said.

The commission eventually sided with Pavlov in late March – more than seven years after she filed her complaint. It ordered the company to pay Pavlov roughly $70,000 in damages.

But New Flooring’s lawyers told the MCAD they plan to appeal. And now Pavlov fears it could take years longer before the case is behind her.

And even if she ultimately prevails, Pavlov, now 35, worries it could be hard to collect. So much time has passed: New Flooring changed its name, and the co-owner who fired Pavlov sold his share in the company and moved back to his native Belarus.

Still, Pavlov said she’s never planning to give up.

"You don't get to treat people that way," she said.

A smoother road to justice

Advocates and two former MCAD employees said the commission needs a number of changes to end the delays.

The most obvious fix would be to hire more workers to handle the crushing load of cases.

“We just need to fund MCAD,” said attorney Susan Howards, who says the agency is understaffed. “And we have to take these kinds of cases very seriously because they change people's lives.”

Some say the commission also needs to streamline its process to eliminate some time consuming legal maneuvers such as objections and continuances. Another option is to push parties harder to work out their differences between themselves. The commission does offer mediation, but it's optional. Murphy, the lawyer with the Disability Law Center, thinks it should be mandatory.

“The earlier in the process that you can start that conversation, the more likely it is that there will be a resolution that both parties will be satisfied with,” Murphy said.

Criminal defense lawyer Carl Williams said that if judges have deadlines to resolve cases, then so should MCAD employees.

“Who at the MCAD is saying: ‘This better be done or no one’s getting promoted’?” Williams said.

Then maybe people filing MCAD complaints today won’t have to wait 10, 15, or 17 years to see their cases in the rearview mirror.

This segment aired on May 27, 2022.