Advertisement

Review

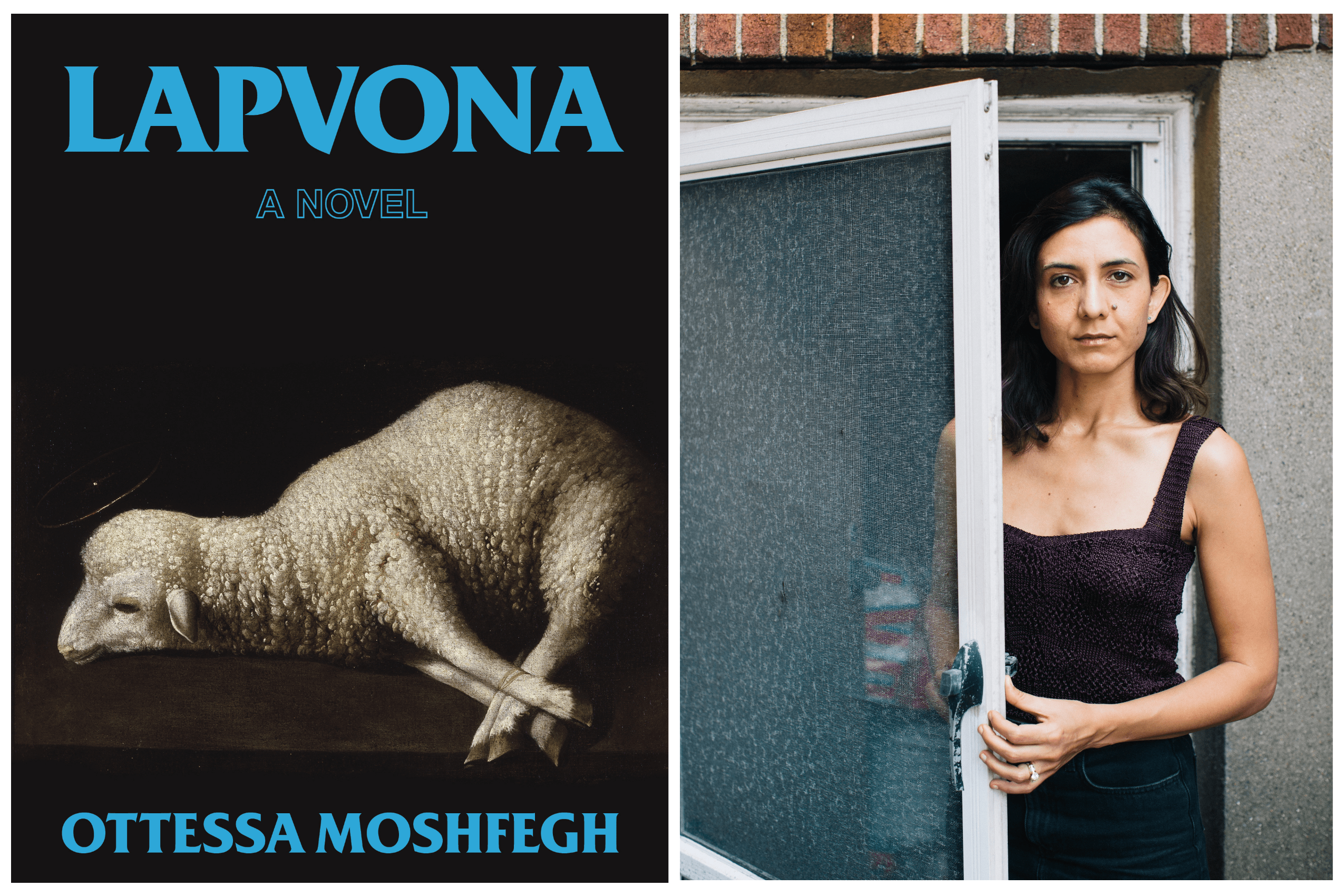

Author Ottessa Moshfegh crafts a medieval allegory about capitalism in 'Lapvona'

Medieval literature speaks often of the goddess Fortuna, a personification of the belief that the fates of men and women were beyond their control, utterly random, and divorced from meaning or justice. She’d spin her famous wheel and sometimes you’d come out on top, other times you’d fall tragically to the bottom. Bad things would happen to good people, and vice versa. No matter how much luck she may have bestowed upon you, eventually, you’d find yourself out of her good graces and suffering some indignity or another. “She heedeth not the wail of hapless woe,” wrote Boethius, “but mocks the griefs that from her mischief flow.”

Which brings me to Ottessa Moshfegh. In her latest book, “Lapvona” (out June 21), she brings her cynical eye and unabashedly forthright style to a tiny, medieval village, crafting an engrossing allegory about capitalism, community and corruption that suggests our fates may not be as random or immutable as they seem.

Lapvona exists somewhere in medieval Christendom, but for all its residents know, it may as well be on Mars. The world beyond the horizon is meaningful to them only as the place where the bandits who loot and pillage their lands come from, and where the fruits of their labor are sent in trade to enrich their lord, Villiam. The town is a grim place; the lord is a wastrel; the priest is a fraud. Nominally Christian, the citizens uphold the barest trappings of ceremony as they continue to put faith in folk remedies and superstitious rituals. They’re more likely to seek the counsel of the aged Ina, a blind witch who lives on the outskirts of the town, than Barnabas, the sham cleric. Beset by all manner of misfortune — plagues, drought, famine, endemic violence, child abuse, pedophilia, rape, cannibalism and exploitation of all sorts — the people of Lapvona are continually fighting for survival, even though it seems that they have very little to live for.

"Lapvona" is at times exceedingly graphic and puts its characters — particularly its women — through a gauntlet of ugly violations that can be difficult to read.

Moshfegh — who, through her books “Eileen,” “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” and “Death in Her Hands,” has become famous for her complex, often brazenly off-putting female protagonists — has opted for a different approach this time. “Lapvona” is an ensemble piece, with a shifting third-person perspective that allows the author to provide a wider view of the village and its culture. But while her narrative style has changed, Moshfegh’s claustrophobic prose and predilection for all things grotesque have not. “Lapvona” is at times exceedingly graphic and puts its characters — particularly its women — through a gauntlet of ugly violations that can be difficult to read. It’s not a book for the faint of heart.

If there’s a singular thread to the narrative, it’s that of Marek, a young, disabled boy who begins the story as a pathologically pious punching bag for his father, a shepherd named Jude. At first, Marek’s uncomplaining acceptance of his pitiful lot in life seems to mark him out as a gentle soul in a harsh world. It quickly becomes clear, however, that he is actually motivated by a malignant, masochistic narcissism. When he falls while fetching water, he is “secretly pleased” and uses a sharp rock to deepen his wounds. “Good, Marek thought. I deserve this hardship. He lived for hardship. It gave him cause to prove himself superior to his mortal suffering.”

There’s more than a little of Mervyn Peake’s Steerpike in Marek. Out playing with the lord’s son, Jacob, Marek causes an accident — perhaps intentionally — that leads to the other boy’s gruesome death, and, thanks to a combination of luck and Villiam’s callous caprice, ends up adopted as Jacob’s replacement. Ensconced in the manor, Marek is safe from the bandits, spends the famine gorging on sausages to the point of vomiting, and is generally oblivious to the misery beyond its walls as he jockeys for the lord’s favor. Slowly, Moshfegh reveals that many of Lapvona’s misfortunes, seen as random occurrences or inalterable vagaries of life, are in fact the result of Villiam’s malevolence. He arranges for the bandits to raid the village periodically, to keep the people in line. He caused the drought, and the ensuing famine, by diverting the river for his own purposes. It’s not Fortuna’s hand on the wheel, it’s Villiam’s.

Advertisement

If there’s a moral to "Lapvona," it’s that while our fates are in fact often beyond our control, they are not necessarily determined by random chance or some divine will...

The women of Lapvona are treated as chattel, largely obedient and silent as custom demands, but Moshfegh provides readers with a window into their tortured inner lives. When Villiam’s wife Dibra grieves over her dead son, she remembers that he “never spoke to her as though she had a mind, but like something to operate, like a clock or compass.” Marek’s mother, Agata, who was thought to have died but instead had hidden herself away in a convent to escape Jude, survives through disassociation. “‘I am an object in the room,’ she told herself. ‘That is all that I am.’ This belief spared her the agony of her own intelligence while she was a slave to the nuns.” When Marek finds her, he is stunned, asking if she is really alive. She can only shrug. “Who could answer such a question?” she wonders. Can what she has be called a life?

“Lapvona” was written during the pandemic and features a flashback in which a younger Ina survives a plague, much to the consternation of her fellow villagers, who are more concerned with the economic opportunities presented by the mass death than her well-being. “She had indeed seen death and she was not afraid of it. What scared her were other people and their immovable selfishness.” If there’s a moral to “Lapvona,” it’s that while our fates are in fact often beyond our control, they are not necessarily determined by random chance or some divine will, but rather by the choices of those who have achieved enough power and privilege to indulge their selfishness.

Hosted by Harvard Book Store, Ottessa Moshfegh will discuss her new book “Lapvona” at the Brattle Theatre on June 24.