Advertisement

Review

From Rodin to Sondheim and Yo-Yo Ma to Leonidas Kavakos, the art in the Berkshires is monumental

Giants walk the hills of the Berkshires. I bumped into quite a few last week. You know some of them: Stephen Sondheim, Yo-Yo Ma, Auguste Rodin, Norman Rockwell and that fallen spawn of Satan, Count Dracula.

There are others you should know if you don’t, like Julianne Boyd, Leonidas Kavakos, Antoine Tamestit, Emily Skinner and Kadir Nelson.

It may be a tad late to get to know Boyd, as the co-founder of Barrington Stage Company is staging her last picture show there, at least as artistic director of the Pittsfield-based company. It’s Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler’s "A Little Night Music" (through Aug. 28), her second go at the show, and it’s a beauty, as are almost all her musicals. (And her non-musicals haven’t exactly been tuna fish either.)

It’s wonderfully staged and cast, but the distinguishing mark of a Boyd musical — whether it’s “Cabaret,” “West Side Story,” “Mack and Mabel” or a two-piano version of “South Pacific” — is a laser-like focus that cuts to the emotional truths of the characters and the story. You don’t go out humming the scenery — there isn’t much in this “Night Music” — you go out humming the songs in ways that resonate differently and deeper than in the past.

That was particularly true in this production of its big hit, “Send in the Clowns.” It has been sung more “beautifully” in the past, but I’ve never heard it sung better than by Emily Skinner, as she sums up all the near-tragic ruefulness and comic absurdity, the sadness and soulfulness that make “A Little Night Music” more than just a charming love story, but a worthy turn on Ingmar Bergman’s finely etched, bittersweet “Smiles of a Summer Night.” Skinner’s acting chops are front and center as well, singing with her eyes as well as her voice. “Isn’t it rich?” It’s the mother lode.

And that’s true of pretty much the whole ensemble of singer-actors backed up gracefully by Darren R. Cohen’s direction of a small ensemble that plays big and Robert La Fosse’s waltz-like choreography. I could have done without Sabina Collazo’s grating giggles as the 18-year-old bride and Mary Beth Peil’s elderly Madame Armfeldt struck me as more dry than wry. But then there’s only one Madame Armfeldt for me — Boston’s own Bobbie Steinbach in both the Lyric Stage and Huntington Theatre Company productions.

Advertisement

So much for the nits. Barrington Stage started out in a high school auditorium in Sheffield, Mass. Boyd and her farewell, “A Little Night Music,” show how she has turned it into not only a great Berkshires theater, but a great American theater. She hopes to direct two plays a year in the future, one in Pittsfield.

I’m there.

Yo-Yo Ma and Emanuel Ax have always made distinguished music together on cello and piano. The late violinist Isaac Stern joined them in trios, forming the Crosby, Stills & Nash of classical supergroups. They have only grown richer in sound since the superlative Leonidas Kavakos has replaced Stern, at least on a pair of excellent Sony CDs of Beethoven and Brahms as well as at Tanglewood last weekend. And if we really want to torture the CSN analogy, violist Antoine Tamestit was the Neil Young of the quartet, joining them at Tanglewood this season for a dazzling chamber concert, making his instrument, a violin on steroids, sing like silk.

The program, “Pathways from Prague,” was the third in a series curated by Ax, who’s marking his 40th straight summer at Tanglewood. The mostly Dvořák concert paired Ax with the three great string players in the first half. Ma and Ax are a proven commodity and the duo even engaged in a standup comedy routine toward the end of the first half. Ma is a one-man sellout every time he appears at Tanglewood (and everywhere else) so this chamber concert was in the Koussevitzky Music Shed rather than Ozawa Hall.

Ma gets deserved credit for his romantic repertoire and receives widespread attention for his crossover work, but I particularly treasure his championing of 20th and 21st-century modernist classical works from Charles Ives to Stephen Albert and Osvaldo Golijov. And so after richly played Dvořák duets with Kavakos and Tamestit joining Ax, Ma and the pianist tackled the gripping pointillism of Vítězslava Kaprálová, who died at 25 in 1940, and the more nostalgic “Fairy Tale” by Leoš Janáček, both played by the duo with their usual great chemistry and charisma.

There was no shortage of either of those qualities after halftime. For all the great musicianship, it was Kavakos whom I found revelatory. A tall sartorial rebel with a musical cause dressed in Johnny Cash black, Kavakos reminds me of the late jazz violinist Stéphane Grappelli. He gives the appearance of effortlessness with his bowing. But like Grappelli, every note is emotively phrased as well as perfectly played. Unsuk Chin wrote her second violin concerto for him, and he and the BSO premiered it last March to well-deserved acclaim.

When the four musicians joined forces for Dvořák’s Piano Quartet No. 2, they looked like they were having the time of their lives — along with the audience. Don’t take my word for it. It’ll be streaming in September.

When you talk about towering talents in the Berkshires you can’t get much higher than Auguste Rodin, particularly his Balzac statue that greets you as you enter the Clark in Williamstown. It isn’t the last time you’ll be overwhelmed.

Part of the must-see call of "Rodin in the United States: Contemplating the Modern" (through Sept. 18) is the proximity that the Clark allows. Rodin has always been one of the highlights for me in any museum, not to mention the Rodin museums in Paris and Philadelphia. But at the Clark, walking right up to “The Thinker,” “The Kiss” or “Cupid and Psyche” gives an even deeper sense of the majesty of his modernist vision and the physicality of his figures. You almost feel like a voyeur looking down on Cupid and Psyche making love. Looking up at the muscularity of “The Thinker” and walking around his torso gives new meaning to “statuesque.” Awe is an overused word these days, but not at this exhibit.

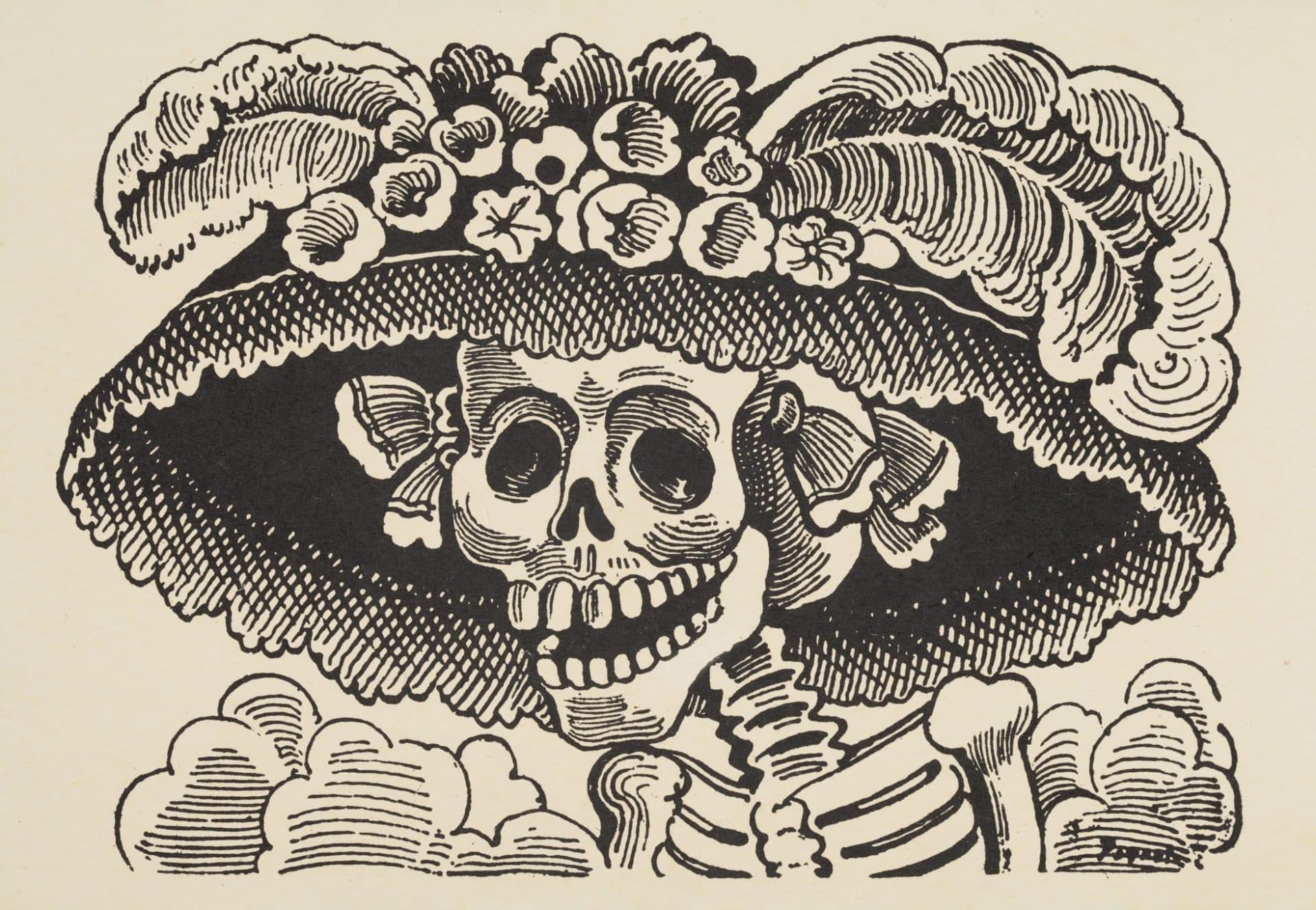

Berkshire museums and other arts institutions have all made honorable attempts to be diverse when it comes to programming, even as the audiences remain overwhelmingly white. The Clark also has an exhibit of José Guadalupe Posada’s illustrations, "Symbols, Skeletons, and Satire" (through Oct. 10), particularly his Day of the Dead calaveras (representations of the human skull). It’s an interesting exhibit, certainly, for its political and anthropological importance, but if you go to the Clark, see it before you go to Rodin. I went afterward and it was anti-climactic.

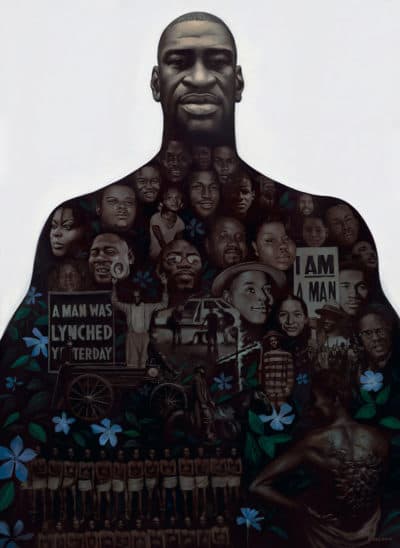

That wasn’t the case at the Norman Rockwell Museum where "Imprinted: Illustrating Race" and "In Our Lifetime: Paintings from the Pandemic by Kadir Nelson" (both through Oct. 30) take us from the shameful stereotypes of the 1600s to the 1960s, including some artwork by N.C. Wyeth and Rockwell himself. It’s one thing to know the history, it’s another to be confronted by the images of this emotionally intense exhibit and wonder what imprint they've left on us. It moves into more contemporary times from the ‘60s onward when African Americans were treated with far more dignity, including by Rockwell, whose civil rights paintings are perhaps his best work. The main source of progress, though, came from Black artists moving to the forefront of representation. But before we get too carried away with saluting American progress, the two exhibits leave you with the takeaway of Kadir Nelson’s bracing 2020 New Yorker cover of George Floyd, “Say Their Names,” with images of violence against Black people imprinted on Floyd’s body.

The four days in the Berkshires did not, alas, end on a high note. As a horror buff as well as a theater critic I was looking forward to "Dracula" by the Berkshire Theatre Group at its beautifully restored Colonial Theatre digs in Pittsfield (through Aug. 27). The production is pretty much the original 1920s play by Hamilton Deane and John Balderston that propelled Bram Stoker’s novel into the sensation that it remains today. Alas, Stoker didn’t live to see his name in lights.

But in highlighting what theater was like before the talkies, this “Dracula,” directed by David Auburn, just shows how poorly the melodrama of action-adventure-horror plays on the stage today. Even actors as accomplished as David Adkins and Jennifer Van Dyck (as a female Dr. Van Helsing) seem like they’re stuck in community-theater over-emoting. Emma Geer as Lucy Seward is the only principal who’s at all convincing. Movies, even in black and white, really did a number on plays like “Dracula,” particularly since the film’s director Tod Browning and screenwriter Garrett Fort improved the script enormously.

Browning was wise, however, in keeping the lead from the play — Bela Lugosi. Whether the Pittsfield Dracula, Mitchell Winter, was wise in not trying to match Lugosi’s eerie performance and exotic accent, he and Auburn haven’t come up with anything else to match the artistry of Lugosi and Browning.

Oh well. All winning streaks come to an end, but even if Count Dracula gets a stake through his heart, Messrs. Dvořák, Rodin and Sondheim live on, thanks to the artistic wizardry of the Tanglewood quartet, the Clark Art Rodin exhibit and in her grand finale as artistic director at Barrington Stage, Julianne Boyd.