Advertisement

Fuller Craft explores food insecurity through art in new exhibit

Millions of people across the country worry about where their next meal is coming from. More than 10% of Americans are “food insecure,” according to the United States Department of Agriculture.

In Fuller Craft Museum’s new exhibit “Food Justice: Growing a Healthy Community Through Art” (on view Nov. 12-April 23), the whole food issue is placed, well, squarely on the table.

What food are we eating? Where does it come from? Who and what are we hurting in the process of growing it? And why do some of us get to eat while others don’t?

In a vast array of media — including ceramics, glass, paper sculpture, handmade books, metalwork, and even live plants — 15 artists in 19 works explore divergent aspects of our food conundrum, and in particular, the growing disparity in the distribution of food resources around the world. Some works take a sweeping view of issues like food waste and corporate agricultural practices, while others provide a personal reflection on what it’s like to grow up living on and working the land.

“Food is a basic human right,” says Beth McLaughlin, artistic director and chief curator at Fuller Craft. “The show really unveils some of the inequities and the complexities of how the food we eat gets to us and how it's not getting to all of us.”

Intensive farming practices, mono-cropping, excessive use of agricultural chemicals and higher temperatures associated with climate change are all factors that account for a precipitous decline in the bee population, according to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. According to Greenpeace, the number of bee colonies per hectare has declined by 90% in the United States since 1962. Three out of four crops around the word depend on bee pollination.

Artist Anna Metcalfe reflects on the importance of bees in her installation “Pop-Up Pollinator Picnic,” featuring 48 hexagonal ceramic picnic plates mounted together to provide a honeycomb effect. Plates in the original show featured a Minneapolis and St. Paul city street map, a reminder, particularly to city dwellers, of the ecosystem on which we depend but sometimes forget as we traverse our asphalt terrain. For this rendition of the show, Metcalfe has adorned her plates with pictures of vegetables and fruits. The cups accompanying each plate feature flowers from those plants pollinated by bees.

“Now, living in an urban environment, I am a member of the rural diaspora,” writes Metcalfe, in the show catalog. Metcalfe grew up in rural Virginia before moving to Minneapolis.

“I see systems of hierarchies and disparities that separate us from each other and the resources that give us life. However, I believe that healing can happen when we are able to connect with the things we all must share: the land and water around us.”

Advertisement

Artists Wendy DesChene and Jeff Schmuki (who call themselves "PlantBot Genetics Inc." in a parody of big agricultural firms) take on corporate agriculture in their installation “Community Hydroponic Garden.” The piece features a live, growing vegetable garden set in tubes placed on a couple of sawhorses. The structure, built of recycled and refashioned commercial products, functions as an actual community project garden right in the gallery. The food grown will be harvested and donated to local organizations.

“By imitating actual corporate practice, we underscore the potential consequences of the global corporatization of agriculture, the natural environment, and public space,” the artists write.

Meanwhile, Stefanie Herr picks up on the same theme in her photographic relief series incorporating hand-cut layered cardboard photographs that become 3D sculptures of carrots, rabbits and cuts of beef and pork. The messiness of real life is juxtaposed with the safe sterility of Styrofoam containers, which starkly point out how disconnected we’ve become from our food sources.

“Most people ignore where their food comes from,” says Herr in the show catalog. “Some children have never seen or touched a real cow in their life, but are perfectly familiar with fingers, patties, meatballs or even Mickey Mouse-shaped minced meat. Skinned and eviscerated, filleted or portioned, neatly packaged and appropriately labeled, animals are treated as mere commodities today and are no longer considered an integral part of a unique ecosystem.”

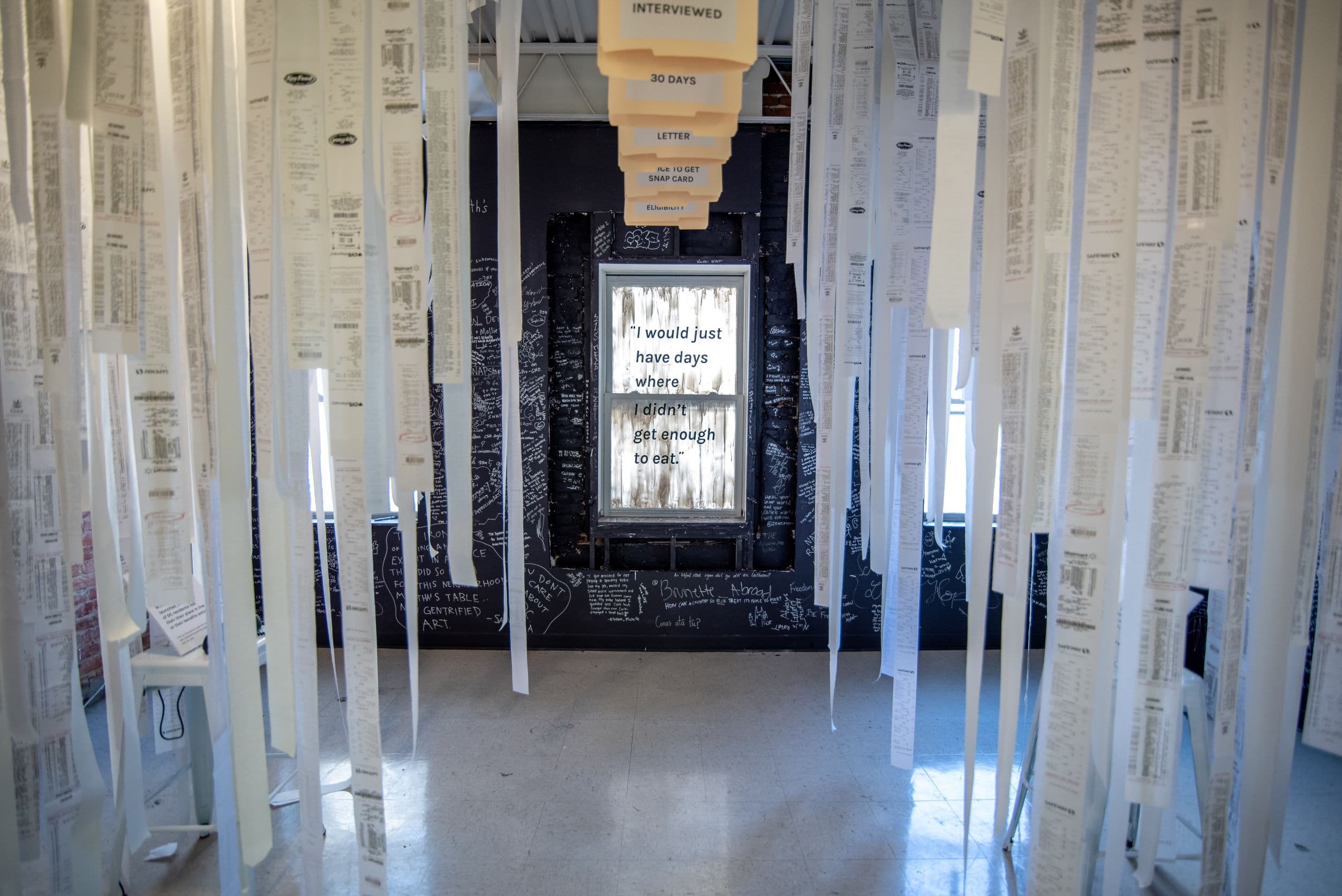

While the industrialization and commodification of food is one ripe theme in “Food Justice,” so is how the government has failed to support the equitable distribution of food. In the installation “Transaction Denied,” by Xena Ni and Mollie Ruskin, a cascade of cash register receipts and manila folders rain down from the ceiling. Amid the stream, an audio plays describing how Washington, D.C. food assistance recipients got lost in the system when the district sought to upgrade its computer system, resulting in a huge snafu. Thousands were left without access to their benefits.

“It evokes the anxiety that I imagine is felt when you're struggling to put food on the table,” says McLaughlin. “It's also really looking at the bias that we tend to have towards people that are in that situation and the failures of the government to really step in and to provide that support and access.”

Metalworker Michael Logan Woodle takes a much more personal approach in his humorous metal pieces that have included a sterling silver and copper hog gravy boat and a silver ladle in the shape of a cow’s udder. Nothing, says Woodle in the show catalog, has been so central to his identity as growing up on a farm that made his family very rich, then poor, then just break even.

“This work is my way of searching for what this land, and the people that worked it, mean,” says Woodle.

Like the original “Food Justice” show that opened at Contemporary Craft in Pittsburgh, Fuller Craft is also planning a full roster of events around collective action for food justice, including a three-hour panel session on food insecurity featuring Commonwealth Kitchen, Black Girls Nutrition, and others. There will also be gallery talks and the installation of a community fridge.

“Craft in particular has the ability to present ideas using materials that are so tactile and familiar to the viewers,” says McLaughlin. “Contemporary craft offers these very vital and excessive entry points for viewers to be able to engage with the work, to reflect upon the issues, to discuss them, and to hopefully take action moving forward.”

“Food Justice: Growing a Healthier Community Through Art” is on view Nov. 12-April 23 at Fuller Craft Museum.