Advertisement

Review

The Brattle celebrates the '90s with two of the decade's most influential indies

This weekend, the Brattle Theatre is going to party like it’s 1995, screening sparkling new digital restorations of two of the Clinton era’s most influential indies. Diametrically opposed in content and especially in tone, Daisy von Scherler Mayer’s “Party Girl” and Gregg Araki’s “The Doom Generation” didn’t drum up much money at the box office during their initial releases, but both became almost instant cult classics that epitomized a very specific moment of Gen X cool. (During my undergrad days as a video store clerk, we couldn’t keep these tapes on the shelves.) One’s a sunny, sprightly comedy while the other is a filthy, ultraviolent exploitation film — you can probably guess which is which from their titles — yet both were connected to youth culture in ways you don’t often see in independent cinema anymore.

We used to learn a lot about people in their 20s by going to the movies. Not so much these days. It could be that the barriers to entry in the industry have become too high, or maybe this generation of artists have migrated to newer, more modern mediums of expression. But now that the mumblecore movement has gotten old enough to be a protagonist in one of its pictures, I’m wondering whatever happened to the hip, buzzy indie flicks about young folks trying to find their way in the adult world. (It occurred to me while writing this that the closest recent analogue might be Jane Schoenbrun’s “We’re All Going to the World’s Fair," a notion too dystopic to think too hard about right now.)

The story of “Party Girl” is so slight as to almost be an afterthought. Spoiled, 23-year-old Mary (played in a supernova of a performance by the pricelessly haughty Parker Posey) drifts from underground raves to all-night afterparties as a doyenne of downtown Manhattan nightlife, mooching off her godmother without an iota of ambition. But facing eviction and finally forced to get an actual — gasp! — job, Mary starts clerking at the local public library and begins putting her life in order with the help of the Dewey Decimal System. It’s a slyly funny inversion of the old “hot librarian takes off her glasses and lets her hair down” cliché, as we watch Mary learn to button up and put on a proper pair of hornrims. She wears them well. Parker Posey wears everything well.

Director von Scherler Mayer conjures the fashionista club kid chaos with ample aid from her star’s personal wardrobe, mixing and matching Vivienne Westwood and Jean Paul Gautier with vintage, thrift shop kitsch. 1995 was the year of Posey’s coronation as “Queen of the Indies,” when the actress also appeared in Noah Baumbach’s “Kicking and Screaming,” Hal Hartley’s “Amateur” and even showed up for a scene in “The Doom Generation.” But no film ever capitalized upon her irresistible imperiousness better than “Party Girl.” Mary is selfish, shortsighted and wears her privilege like it’s Prada. In any contemporary picture, she’d surely be the villain, yet here we can’t help but root for Posey in all her sassy, screwball vanity. (I still can’t believe someone cast her in a “Superman” movie, and she didn’t play Lois Lane.)

“Party Girl” has some of the exuberance of Susan Seidelman’s 1980s downtown bohemian classics “Smithereens” and “Desperately Seeking Susan” while also capturing a now-precious time capsule of Wigstock-era queer club culture. It opens with a cameo by RuPaul’s old roommate Lady Bunny, and yes, Liev Schreiber as Mary’s bouncer ex-boyfriend Nigel. (He might be the most unconvincing Englishman in all of '90s cinema, and I’m including when Kevin Costner played Robin Hood.) There’s a ramshackle, low-stakes charm to the picture that feels sincere. “Party Girl” sends you out smiling, which is something that will never be said about “The Doom Generation.”

Araki’s lurid, smirking inferno of a movie first screened at the Sundance Film Festival in 1993, but concerns over its appalling content got the film dropped by its original distributor and eventually released by a rival company two years later in an unrated, truncated edit. This newly remixed and remastered director’s cut restores all the excised material — including an infamous scene of genital mutilation with gardening shears — as well as an ear-shattering soundtrack and a retina-scalding color scheme pushing the limits of the 4K digital image. It’s an overwhelming sensory experience by design.

Advertisement

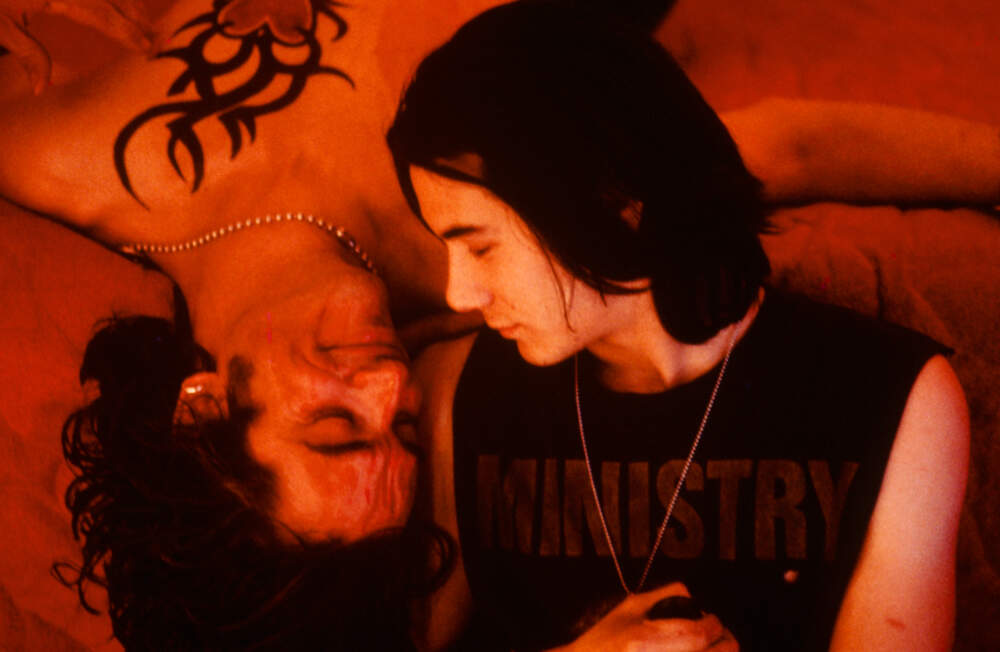

“The Doom Generation” is jokingly billed in the opening credits as “a heterosexual movie by Gregg Araki” because the New Queer Cinema maverick behind groundbreaking gay films “The Living End” and “Totally F***ed Up” was promised a significantly larger budget if he made his next picture about straight kids for a change. This is why we begin with sweet, virginal Jordan (James Duval), who is too frightened of AIDS to have sex with his girlfriend Amy, played in a barn-burning turn by Rose McGowan. Instantly iconic in her fire-engine red lipstick and an Anna Karina wig, Amy is brash, foul-mouthed and seems to subsist entirely on speed, cigarettes and diet soda. The trouble begins when these two encounter a sleazy hitchhiker named X (Johnathon Schaech), who has a hair-trigger temper and a tattoo of Jesus on his private parts. After a botched robbery during which X accidentally decapitates a convenience store clerk, the three fugitives hit the highway heading nowhere fast.

For some reason, the early '90s were overrun with movies about murderous young lovers on the road — bastard sons of “Badlands” and “Bonnie and Clyde” like “Wild at Heart,” “True Romance” and “Natural Born Killers.” Araki was clearly aiming to make the lewdest, rudest and most transgressive of them all. (Sorry, Oliver Stone still won that contest.) But while Araki's sensibility might sometimes lean a little too hard into juvenilia — the murdered shopkeeper is named Nguyen Coc Suc, for goodness' sake — it’s tough not to admire the sheer, obnoxious audacity of “The Doom Generation.” The film is a sustained, 83-minute affront to common decency and good taste, inspiring one of Roger Ebert’s angriest zero-star reviews, in which the critic was careful to explain: “I do not object to the content of his movie, but to the attitude.”

I actually admire the attitude more than the content, which can sometimes get pretty puerile in its ornate obscenity. What stings and lingers in the memory about “The Doom Generation” are its feverish manifestations of AIDS anxiety and the evocations of empty, junk food nihilism with an end-of-the-century, apocalyptic edge. Araki being Araki, devotes his “heterosexual movie” to exploring what a slippery slope the Kinsey scale can be. (It's an absurdly sexy picture in ways American movies aren't allowed to be anymore.) But at the risk of getting into spoilers, it’s also worth noting that the very moment these characters find contentment in an arrangement outside of the traditional male-female paradigm, they’re beset upon and brutalized by a gang of homophobic neo-Nazi psychopaths.

Araki’s obviously going for an “Easy Rider” ending here, complete with that aforementioned gardening shears business and the unshakable sight of McGowan being raped atop an American flag. However blaring and unsubtle, the movie’s message remains distressingly relevant today: You can get away with all sorts of sins and crimes and maybe even murder, but in many parts of this country, what's considered sexually “deviant” is still punishable by death. We like to think that we’ve come so far in the 30 years since “The Doom Generation” first screened at Sundance, but watching the news these days, I’m not so sure.

“Party Girl” and “The Doom Generation” are screening at the Brattle Theatre from Friday, June 16, through Tuesday, June 20.