Advertisement

Mass. set a record for opioid overdose deaths. Black residents were hardest hit

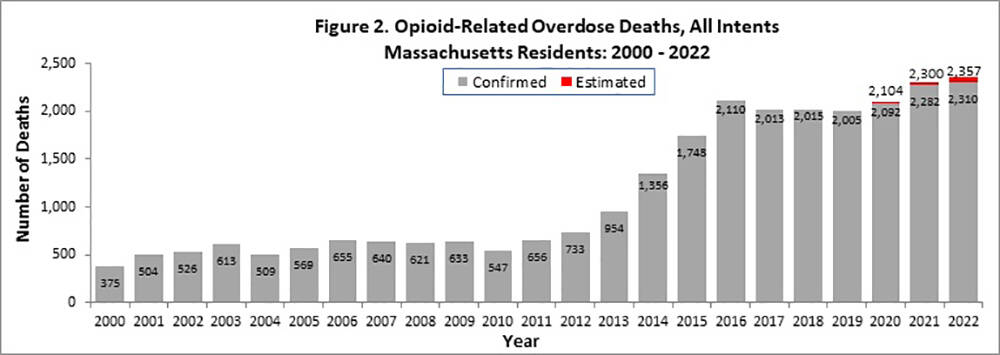

Massachusetts has set another record, one no one will celebrate. Preliminary state data shows there were 2,357 overdose deaths in 2022. That’s 57 more deaths than in 2021, and an increase of 9% from the highest point before the COVID pandemic.

More than six people died, on average, every day.

“These numbers are sobering,” said the state’s Public Health Commissioner Dr. Robbie Goldstein. “We continue to see increases we don’t want to see.”

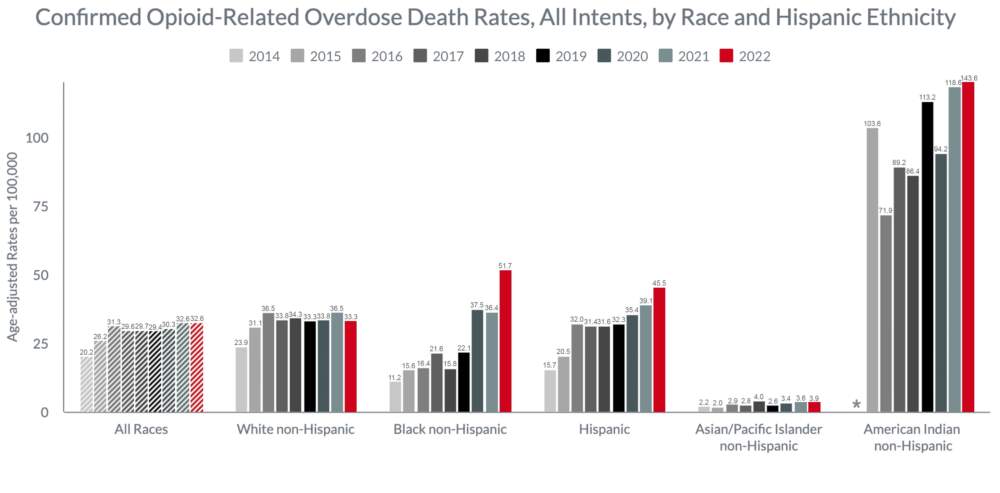

The most dramatic increase, according to the data released Thursday by the state’s Department of Public Health, was among Black people who use drugs. The preliminary numbers show overdose deaths rose 42%. It’s more proof of racial disparities in the drug overdose crisis.

Many factors contribute including this: Black drug users are less likely to receive medications used to treat an addiction. Some researchers say that’s a result of decades of misguided medication and treatment policies.

The change in fatal overdoses varied substantially across the state, the data shows. Several counties in western Massachusetts saw double-digit decreases last year, while fatalities rose 14% in Plymouth County and 18% in the Worcester area. Worcester’s commissioner for health and human services, Dr. Mattie Castiel, says it’s time to try overdose prevention sites, where people can consume drugs under clinical supervision.

“They prevent deaths, which we need because of our numbers,” said Castiel.”They also bring people into contact with all kinds of other health care and services, including treatment.”

Gov. Maura Healey’s administration plans to conduct a feasibility study of overdose prevention centers, which are sometimes called supervised consumption sites. It’s been four years since a state commission recommended one or more pilot sites in Massachusetts. Goldstein says the new study will be completed by the end of the year, but advocates are frustrated with the slow progress.

Advertisement

The Healey administration released an opioid strategy plan with the fatality numbers. It includes some new initiatives: vending machines that will dispense clean needles and other harm reduction supplies, an overdose prevention hotline, and a data dashboard to help communities understand their specific challenges and ways to address them.

The state plans to continue widespread distribution of naloxone to fight the powerful opioid fentanyl. The drug was present in 93% of people who died after an overdose last year. Goldstein said that 50,000 nasal spray kits distributed since January have reversed at least 700 overdoses so far. There is concern that when naloxone is made available over the counter later this summer it will become unaffordable for many who need it.

“We’re deeply committed to addressing substance use disorder in a range of ways including providing resources to communities to reverse the trend,” said Goldstein.

A key piece of the administration’s plan is a significant increase in spending on treatment. A study published earlier this month in the journal JAMA offered daunting estimates of how much more treatment is needed in Massachusetts to curb overdose deaths.

“We have to change things substantially. If we don’t, we can’t expect big changes in overdose deaths. That’s what these figures are telling us.”

Jagpreet Chhatwal, Mass General Hospital

The researchers found that doubling the number of people starting treatment and continuing for at least six months would reduce deaths by 16%. It would take an “aspirational” five-fold increase to cut fatal overdoses by 27%, the researchers estimated.

“We have to change things substantially,” said lead author Jagpreet Chhatwal, a researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital. “If we don’t, we can’t expect big changes in overdose deaths. That’s what these figures are telling us.”

Even doubling the number of people in treatment doesn’t seem realistic in Massachusetts right now. The state lost treatment beds and space in outpatient programs last year, which may have contributed to more deaths. A report from the Association of Behavioral Healthcare found that most of the reduction happened in programs that accepted patients on MassHealth, the state program for low income residents and children.

The primary challenge is staffing. The report showed 28% of nursing positions in outpatient opioid treatment programs were vacant as of last April. In some residential programs the nursing vacancy rate was as high as 48%.

One reason for the staffing shortages is low reimbursement rates which makes it difficult for facilities to offer competitive salaries. The report says the lowest rates are for patients covered by MassHealth.

The Healey administration is spending $100 million to boost MassHealth reimbursement rates.

“We are hoping that the investment will reverse the closure of program beds and bring them back online,” said Lydia Conley, president and CEO of the Association for Behavioral Healthcare.

Doubling the state’s treatment capacity would require a more substantial investment in both the current and future workforce. The state has pledged more than $110 million in student loan forgiveness for people who enter mental health and substance use-related fields. Peer counselor, recovery coach and other training is covered, in addition to psychiatry, nursing, social work and other roles. Conley is urging the state to fund programs that will introduce young people to the field, like paid internships.

Using pharmacists to help manage patients in addiction treatment could also help expand access.

In the midst of the on-going drug overdose crisis, there’s a lot of attention on helping people who are already addicted or in recovery. Chhatwal says addressing the mental injuries and stresses driving substance use need more consideration as well.

“We can’t wait until it’s too late,” he said.