Advertisement

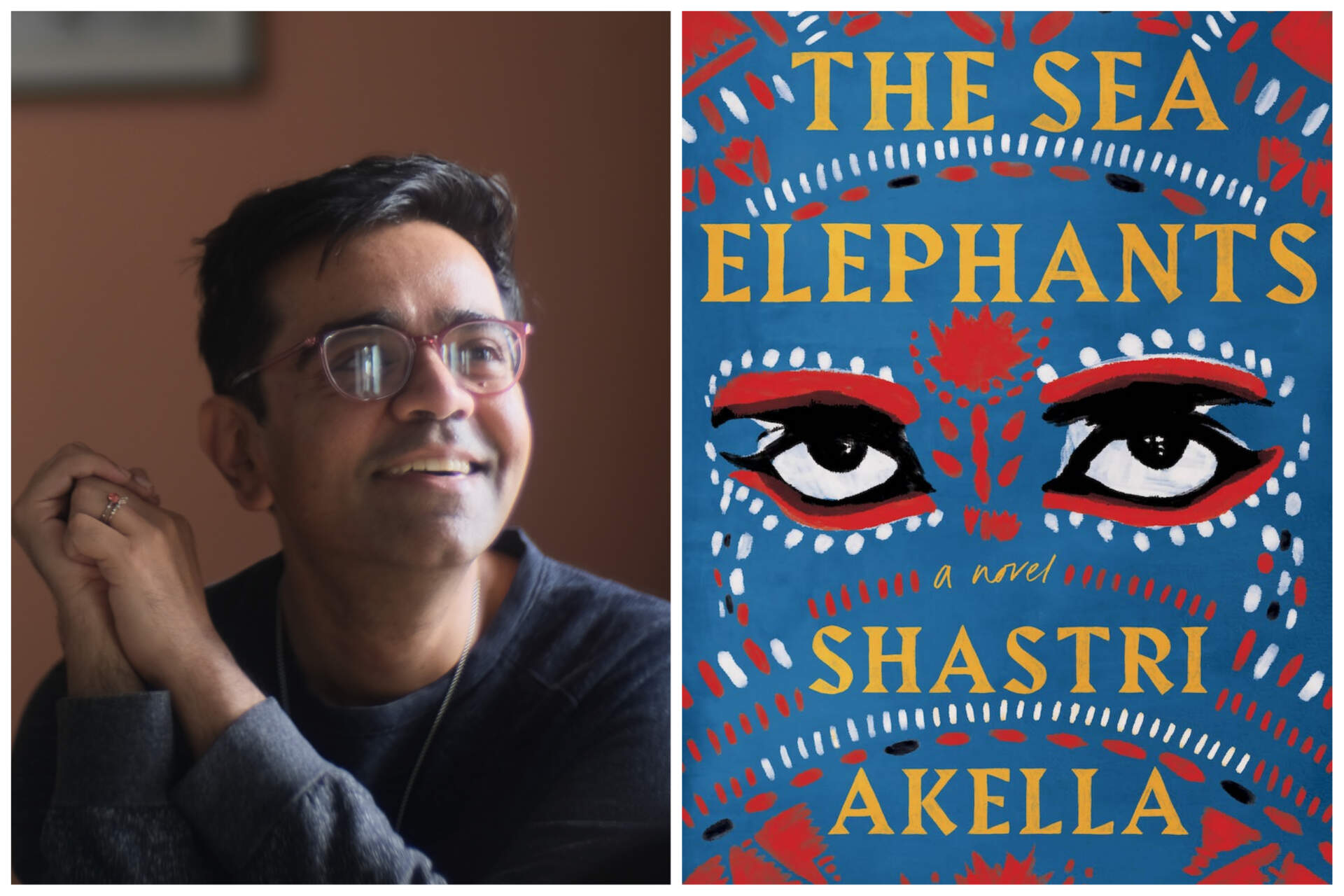

New novel 'The Sea Elephants' hits every note of the human emotional spectrum

Contemporary Western society romanticizes the idea of running away to join the circus — abandoning life’s responsibilities for a whimsical life on the road. But the reality of traveling performers has historically been born out of necessity and survival. In Shastri Akella’s debut novel “The Sea Elephants” (out now), a young man in 1990s India joins a street theater troupe as a means of physical safety but ends up on a journey of self-actualization and healing intergenerational trauma.

The title of the novel comes from the Hindu tale of the sea elephants, the favorite story of protagonist Shagun and his younger twin sisters, Mud and Milk. The myth’s first appearance in the novel goes:

“The gods took away the first ancestor of the sea elephants, coveting him for his exceptional beauty — tusks blue, body ivory. The trauma of that original separation haunts every sea elephant thereafter … Only the soul of a drowned child makes their suffering manageable.”

As Shagun grieves the untimely deaths of his sisters, he carries the story of the sea elephants from his hometown along the Bay of Bengal to boarding school, a traveling theater troupe and a teaching position in Chamba. Each time the myth appears on the page, the story changes to reflect Shagun’s evolving understanding of his sexuality, his relationships with his parents and his trauma. “The Sea Elephants” is an emotional coming-of-age story spanning eight years as Shagun becomes a confident actor, falls in love with a Jewish man and reclaims the myths that once sought to exclude queer narratives.

Navigating grief and identity through storytelling

When Mud and Milk tragically drown, their father, Pita-jee, returns to India for the first time in Shagun’s memory. Indignation ignites within Shagun towards his father. The man who never met and doesn’t appear to grieve his daughters suddenly has a lot of demands for how his 16-year-old son should be performing masculinity. Shagun’s only source of solace is “The Dravidian Book of Seas and Stargazing,” the book of Hindu myths his mother, whom he calls Ma, read to him, Mud and Milk growing up. The stories of the gods help Shagun keep the twins’ memory alive while offering escapism from his now-tumultuous home life.

To evade the notion that Pita-jee’s absence caused Shagun to exhibit feminine qualities and the threat of an early roka (the pre-engagement phase of Punjabi arranged marriages) to a gender he knows he’ll never be attracted to, Shagun applies to boarding school. But his classmates are even more cruel than his father, so Shagun seeks escape once again. This time, he finds it in the form of a street theater performance during the local Ram Navami celebration. The actors invoke the stories of the gods in a way that nourishes Shagun’s love of the epics, reminds him of his sisters and Ma and sparks the possibility of a life where his gay identity is embraced, not scorned.

This heart-wrenching story of a teenager unable to process his grief turns into a frantic extrication when Shagun learns Pita-jee plans to force him into conversion therapy. The novel reflects how homosexuality was punishable by a ten-year prison sentence in India until 2018. Because a nomadic lifestyle would make it difficult for his father or the authorities to locate him, Shagun’s dream of joining the theater troupe becomes a necessity. Despite the threats that never stray far from Shagun’s mind, becoming an actor and forging friendships with his troupe members brings Shagun hope and joy.

“The Sea Elephants” portrays the affirming power of queer found-families. While Shagun is at odds with his parents, he first finds unconditional support from the acting troupe and, later, from his boyfriend Marc and new friends.

The fluidity of performance and the performance of gender

Author Akella expertly incorporates the stories of Hindu deities to illustrate the values of the characters and 1990s Indian society at large. At the beginning of the novel, Akella cleverly contrasts Ma’s favorite deity Krishna, the god of love and compassion, with Pita-jee’s favorite deity, the masculine and athletic Hanuman. Shagun’s parents present a united front in their decisions about his future, and he can’t reconcile why his loving mother who raised him would side with his harsh and absent father. Throughout the book, his love of Hindu mythology is at odds with some of the stories that demonize queer people and minimize women.

Acting allows Shagun to interpret the gods for himself. He says, “Male-female, young-old, god-demon, human-animal: I swam across binaries like a fish moving from one river to another at the point of confluence.” His friends in the theater troupe teach Shagun that to be an actor is to be fluid. And over the course of the novel, Shagun learns that some Hindu myths have been altered over time to censor the original Sanskrit writing that portrayed fluid gender identities and sexualities in a positive light. One powerful example is Krishna’s teachings in the scripture Bhagavad Gita, where he says the body is an earthly suit and souls have no gender. Shagun wonders why the gender of his soulmate should matter if his own soul is without gender.

Another strength of the novel is how Akella draws parallels between Marc’s family history alongside Shagun’s personal experiences. Both sets of Marc’s Jewish grandparents fled Austria when the first Nazi concentration camp was erected in 1933, “leaving behind their belongings, their homes, their histories,” Marc says. Like Shagun’s departure, “It wasn’t so much the right decision as the inevitable one.” Shagun learns that Jewish people have migrated to India for hundreds, if not thousands, of years in the wake of religious persecution and forced conversion. Like the Judeo-Malayalam language (a blend of Hebrew and the local language), Shagun and Marc’s relationship feels like a thematic nod to the coexistence of their respective cultures blending into one. By fighting for their own joy, they are slowly healing their own traumas and the traumas of the family that came before them

The emotional truth of fiction

Akella was born in India and worked for Google before receiving his MFA in creative writing and a Ph.D. in comparative literature from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. To inform his writing of “The Sea Elephants,” Akella shadowed a theater troupe across India, interviewed men who endured conversion therapy centers and drew from his personal experiences in cultivating queer community, joy and resistance.

As a reader, I felt those lived experiences imbued in this novel. The magic of theater is a visceral experience that sparkles on the page. The anguish of a family who doesn’t accept their child’s identity is soothed by the balm of friends who do. The horrors of homophobia are displayed alongside resplendent queer joy. The acceptance of individual identity without needing to divorce cultural identity is a drumbeat that begs to be heard. “The Sea Elephants” takes the reader on a journey from coast to coast and hits every note of the human emotional spectrum along the way.

Shastri Akella will discuss “The Sea Elephants” at Harvard Book Store on Monday, July 24, at 7 p.m. The event is free, and tickets are not required.