Advertisement

The Brattle's Dede Allen retrospective honors a film editor who redefined American cinema

Legendary film editor Dede Allen was born in 1923. She was the daughter of a prominent surgeon and his actress wife — which, if you stop and think about it, is pretty much the ideal genetic background for someone spending a career cutting and stitching together onscreen performances. She’s maybe the only primary creative force of the 1970s New Hollywood movement who never became a household name. And yet, film fans in the know revere her like a goddess. Hagiographies of that particular era tend to trend toward boringly masculine director types, but it was this prim and proper female cutter who redefined the shapes and sounds of the most fertile decade in American cinema. Allen brilliantly changed the way contemporary movies look and feel. The Brattle Theatre’s “Dede Allen Centennial” showcases 13 of her iconic classics, screening every Wednesday for the rest of the summer.

The Brattle Film Foundation’s creative director Ned Hinkle told me, “We’re always looking to celebrate film professionals that fall outside the usual, particularly when a centennial rolls around — screenwriters, cinematographers, producers and editors are often overlooked as unique creative individuals in their own right. Like many of the female creatives who worked alongside male directors and executives in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, Dede Allen was a pivotal and often unsung component of the New Hollywood movement.”

Any Allen retrospective should probably begin and end with “Bonnie and Clyde.” Jagged and electrifying, director Arthur Penn’s 1967 classic remains the demarcation line between stodgy Old Hollywood and something more dangerous and frighteningly new. It’s a funny, alarming picture interrupted by Allen’s increasingly disconcerting editing, which incorporates French New Wave jump-cuts into producer-star Warren Beatty’s cornpone Americana and occasionally overwrought metaphors about the media and his character’s gun-toting impotence. Appallingly hilarious, “Bonnie and Clyde” is a film that still gets under your skin, angry and upsetting. Allen will probably always be remembered first and foremost for the film’s final slow-motion massacre, which blew the doors open for depictions of violence in American cinema with a spasm of bloody, orgiastic beauty. Some say the movies have never recovered.

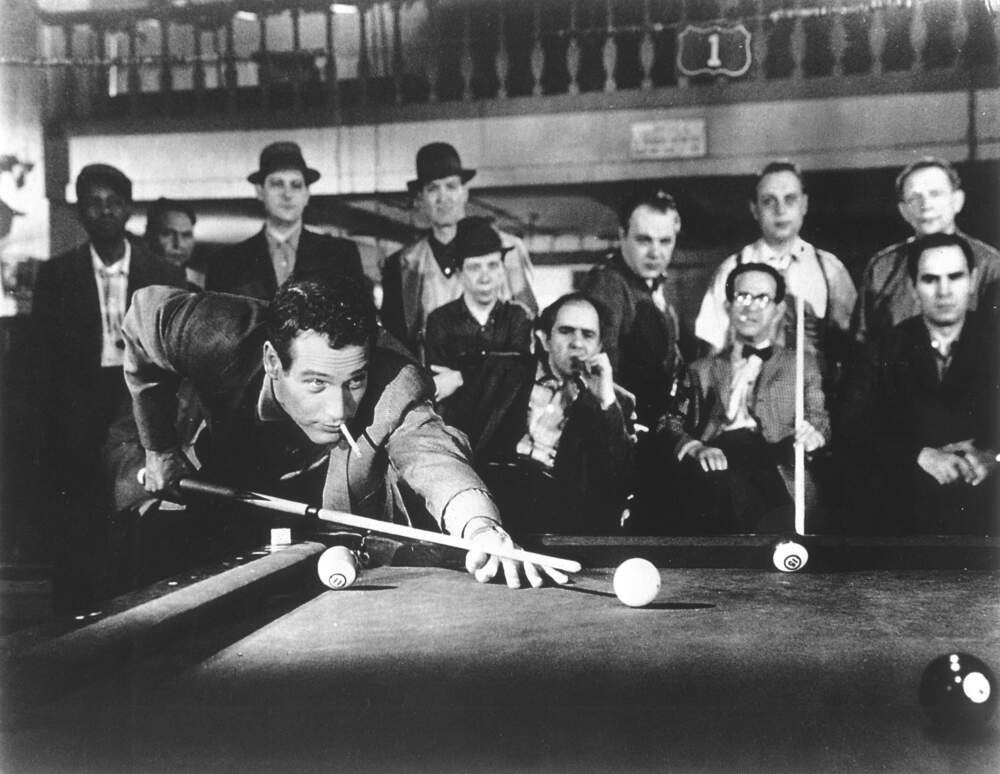

Allen abandoned conventional modes of “matching” the action, ignoring continuity errors and cutting by her gut. The Brattle series kicks off with her first major film, "Odds Against Tomorrow.” The 1959 noir — annoyingly unavailable to stream — stars Harry Belafonte as a beleaguered, gambling-addict lounge singer pressured into a bank robbery alongside Robert Ryan’s seething, racist sidekick. Director Robert Wise came out of the project praising Allen as “a director’s editor.” (He would know, as 18 years before he edited “Citizen Kane.”) As part of a Double Feature that day, the theater is also screening Robert Rossen’s 1961 “The Hustler,” in which Allen’s deft cutting expands and compresses time to a delirious extent in those smoky pool rooms according to the hard luck of Paul Newman’s “Fast” Eddie Felson and Jackie Gleason’s Minnesota Fats.

Sidney Lumet once said, “Dede Allen had a rare ability of divining a director’s intent. And once she saw it, she could fulfill it better than the director.” Calling her “the only great editor I’ve ever worked with,” Lumet had no choice but to trust her with “Serpico,” which was stuck with such a short shooting and post-production schedule he barely got a look at the picture before she’d finished it. The movie’s slippery, elliptical time lapses were natural for Allen’s gifts. But these two made their masterpiece two years later with 1975’s “Dog Day Afternoon.” Grounding an insane true story in specific, everyday mundanity, the tale of a disgruntled Vietnam vet (Al Pacino) holding a Brooklyn bank hostage in order to pay for his lover’s sex change operation unfolds with no music or orchestral score, relying entirely on Allen’s cutting for its internal rhythm. (Twenty years later, John Hughes would cite “Dog Day” as the reason he hired Dede Allen for “The Breakfast Club.” Who else could cut a compelling picture out of characters stuck in an ugly, institutional space?)

Advertisement

We only hear one song in “Dog Day Afternoon,” during the opening credits set to Elton John’s “Amoreena.” It’s an incongruously Southern California tune cued to a New York City symphony while we watch documentary footage of folks from all five boroughs trying to beat the heat on a sweltering August day. Sir Elton is gradually overwhelmed by street sounds and honking horns. The panoramic collage shrinks down to Pacino’s getaway car, the soaring song relegated to his tinny radio. The movie has started, and we haven’t noticed. Allen allows it to sneak up on you.

It’s probably my favorite scene she’s cut and my favorite opening credits ever. But among actors, Allen was foremost known as “a performance editor,” able to sift through dozens of takes to extract the best from them. Estelle Parsons is fond of noting that she only ever made two movies edited by Dede Allen, and those are the only two movies for which she was nominated for an Academy Award. (Parsons won for “Bonnie and Clyde” and probably should have for “Rachel, Rachel.”) “I love and admire Arthur Penn and Paul Newman, the respective directors,” she said, “But I do credit Dede for those extra frames that give a performance the personal impact on the audience.”

I don’t think Al Pacino (my favorite actor) was ever better than he was in “Dog Day Afternoon.” And I don’t think Gene Hackman (a close runner-up) was ever better than he was in “Night Moves.” A sunlit Florida noir and Allen’s fourth collaboration with director Arthur Penn, the movie is an elusive mystery that slips away from the protagonist — a detective story about a detective outsmarted at every turn. The gruff, bullying Hackman is so sad in the picture, lost and forlorn, while Allen’s editing leaves his scenes hanging in the air for just a few extra seconds at the end of every take. We can always see that he’s bluffing and falling apart. “Night Moves” is showing with the hard-to-find Debra Winger 1984 neo-noir “Mike’s Murder,” which I vaguely remember as an HBO late-night staple that had a similarly unsettling, unresolved vibe.

Allen’s reunion with Warren Beatty is one you want to see on a big screen. She and co-editor Craig McKay oversaw more than 60 assistants in the making of “Reds,” Beatty’s sprawling, swooningly romantic 195-minute epic about the Russian Revolution that somehow became a massive hit in Ronald Reagan’s America, probably because early 1980s Diane Keaton was one of the most beautiful camera subjects who ever lived. Amid the mountains of footage shot by Beatty and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, Allen and McKay threaded the documentary testimony of onscreen “witnesses” as ironic counterpoints to the star director’s delirious mythmaking. It’s a gorgeously edited meta-movie, with real-life folks like Henry Miller deflating the “Doctor Zhivago” of it all, while we still fall for it anyway. Plus, Jack Nicholson plays Eugene O’Neill in maybe his greatest performance ever. Again, Allen had that effect on actors.

In the year 2000, director Curtis Hanson famously coaxed Dede Allen out of retirement to edit his wonderful “Wonder Boys,” for which she received her third Academy Award nomination. I wish the film was included in the Brattle retrospective. (After she lost, the great Thelma Schoonmaker said, “I would trade one of my three Oscars happily if Dede Allen could have gotten one.”) Allen had a tremendous gift for comedy, and while the Brattle series does include “The Addams Family,” I feel there’s one more movie we need to mention.

Just last week, a friend was watching the magnificently profane 1977 Paul Newman hockey comedy “Slap Shot” at Quentin Tarantino’s New Beverly Cinema. For those of you who didn’t happen to grow up in the 1980s when “Slap Shot” was on cable television every afternoon, it’s a spectacularly filthy movie full of colorful trash talk written by Framingham’s own Nancy Dowd. It’s also a very insightful picture about men behaving badly, scripted and edited by women who probably know us better than we know ourselves.

A furious young female made a big show out of walking out of the film, announcing to the lobby, “I can’t believe this movie was written by a woman!” I told my buddy he should have called after her, “It was also edited by a woman named Dede Allen. She was the best.”

"Dede Allen Centennial" plays at the Brattle Theatre from Wednesday, July 19 through Wednesday, Aug. 30.