Advertisement

From a pint-sized Picasso to a tiny commode, the MFA takes miniatures seriously

Dollhouses, Monopoly pieces, action figures, Lilliputians, "The Incredible Shrinking Woman." What is it about tiny things that tickle, and toy with, our imaginations?

“Miniatures are both appealing and sometimes unsettling,” mused Courtney Harris, Museum of Fine Arts assistant curator of Decorative Arts and Sculpture, Art of Europe. “They can be cute and whimsical, but also uncanny because we’re surprised or startled by their size.”

Harris herself was surprised when she started noticing a trove of tiny pieces in the MFA's European decorative arts collection. Her radar for the museum's teensiest holdings clicked on, and she set out to find more minis from other time periods and cultures in an array of media. Let's just say Harris scored.

Now, about 100 tiny objects fill the exhibition “Tiny Treasures: The Magic of Miniatures.” Among them, a pint-sized Picasso, Stuart Little-scaled silverware and a bejeweled bicycle pin with itty-bitty spokes and pedals.

According to Harris, a “miniature” is defined as something significantly smaller than its ‘parent’ object. “That means that it has to be seen and understood with relation to something else. A doll's house chair might be 2 inches tall when a full-size one would be 3 feet tall. The comparison is pretty straightforward for three-dimensional works of art, but gets stretched a bit when we’re talking about two-dimensional things like paintings and prints.”

Little objects can be easy to pass by because, well, they're so darn small. And because of their diminutive size, they're not always taken seriously. “They can be relegated to the realm of children or toys,” Harris said. “Hardly any works in the exhibition were made for play.”

Harris argues miniatures matter because they help us explore our human need to understand our own size and scale in the world. The objects “force us to be aware of ourselves in relation to them,” she said. “They demand our attention because we want to 'figure them out.'”

Harris shared her thoughts about a few highlights from “Tiny Treasures.” The words below are hers, lightly edited.

A pint-sized Picasso

Courtney Harris: "The Picasso painting 'Stuffed Shirts' is very much an outlier in his body of work. It’s really small (about 5 by 9 inches) and not at all abstract, dating from around 1900 when he was working in Paris. The level of detail in the painting is pretty incredible — especially in the layering of paint colors in the skirt of the central figure. I think it shows the versatility of him as an artist that he can make something like this which is so insular and absorbing and also huge, immersive, overwhelming works like 'Guernica.'"

Silver for a Dutch dollhouse

"There’s a strong tradition of miniature silver making in the Netherlands in the 17th and 18th centuries. Silversmiths sometimes worked in both miniature and in full-size examples, so a potential customer could have ordered a candlestick for their home and for their doll's house from the same craftsperson. Arnoldus van Geffen from Amsterdam was one of the best-known miniature silversmiths. Incredibly, some of the mini objects even bear his hallmark, or signature, identifying them as his work."

A bejeweled bicycle brooch

"The bicycle brooch is a great example of how miniatures make big ideas more portable. Possibly made in England in the 1890s around the time when bicycles were becoming increasingly popular, this brooch might have been worn by a woman who appreciated the way a bicycle offered her increased independence. With the suffragette movement gaining momentum, wearing a brooch like this would not only have been a fashion statement but likely a political one too."

An ivory netsuke

"I knew when planning this exhibition that I wanted to include a number of netsuke, or small toggles from the inro box worn as part of Japanese traditional dress. There are two animal netsuke in the show, an ivory rabbit and a wooden monkey, but this one is doubly miniature and therefore really special. It’s a small clam shell, which is opened slightly to reveal three figures in a scene from the life of Ono No Komachi, a poet, who is washing a book of poems in a basin in the foreground. The level of detail of carving and then highlighting with ink is incredible, creating an enchanting miniature world."

The mini basket

"Fanny Williams’ miniature basket looks pretty big in a photograph, but it’s only about 2 inches tall. Williams is a member of the Nuu-chah-nulth community and made this basket for the tourist trade. However, it does relate to full-size baskets made and used within the community. Making a small version for trade was a clever idea because it used less materials, took less time, and was more marketable and portable."

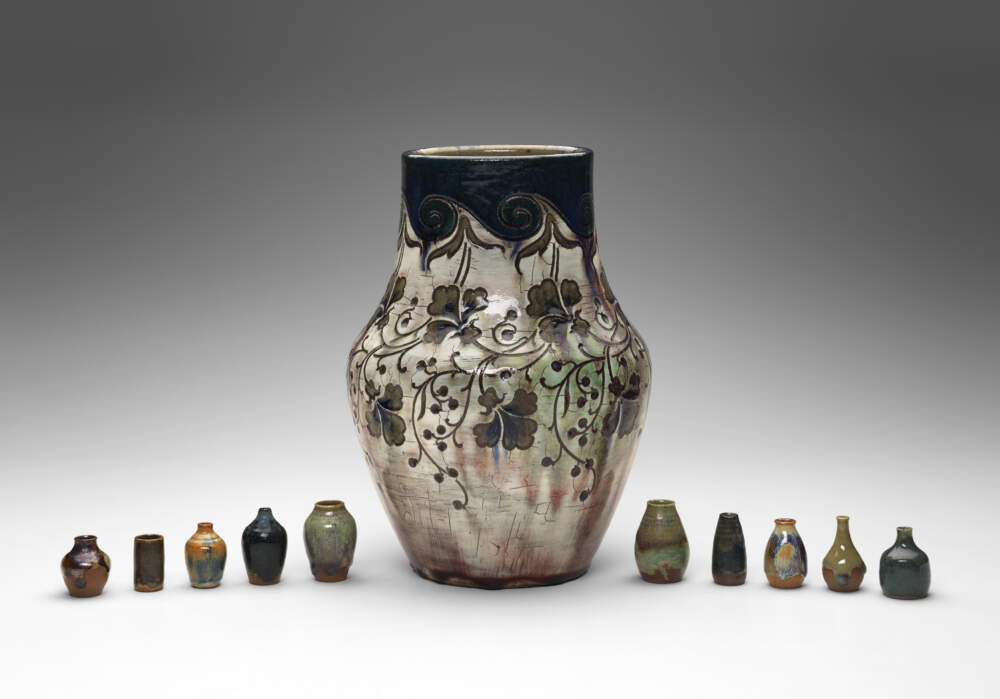

Little glazed ceramic vases

"The miniature vases by Auguste Delaherche are some of my favorite objects in the exhibition. They’re paired with a full-size vase by the same artist. Delaherche, a French Potter, made these mini vases — the museum has 50 — as a way of testing out different forms of vessels. And, more importantly, for experimenting with different glazes or surface decoration. By trying it out in mini form first, he was saving time and materials. Once he learned what worked well, he could then employ that technique in his full-size works of art.

I hope visitors will be enchanted by the miniatures they see, but also that they walk away realizing miniatures have much more to them than meets the eye."

"Tiny Treasures: The Magic of Miniatures" is on display through Feb. 18 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.