Advertisement

How closing shelter doors could push families into illegal and unsafe housing

The Massachusetts family shelter system is in a moment of great uncertainty.

State officials warn the system is almost full. Within days, it is likely to hit 7,500 families. When that happens, they plan to place additional families who qualify for shelter on a waitlist. In emergency regulations filed Tuesday, they also created a path to limit how long a family can stay in shelter.

Advocates say these measures could lead to unsafe conditions for families with children and pregnant women already in dire straits. They've urged state lawmakers to add money to the shelter budget and take steps to protect families. But a legal challenge from advocates and the families they represent has so far failed to halt the creation of a waitlist.

Experts have raised alarms, arguing that when shelter doors are closed, families turn to dangerous and even illegal housing that leaves them increasingly vulnerable to exploitation. For Neghumi and her family, the search for safe housing took many months.

Five on a mattress

Neghumi’s journey to Massachusetts started on a roadside in Peru.

For years, she worked alongside her mother and husband as a street vendor. She sold clothes, and her husband sold fruit. He even had an entertaining routine to draw customers: a contraption on his cart would turn the fruit in circles as he pushed.

But street gangs charged them fees to work inside their territory — fees Neghumi couldn’t pay.

In response, Neghumi said, members of the gangs beat her and broke her nose. And then, they came back armed and threatened to kill her.

“That’s when I said, ‘I'm just going to abandon everything. This is not worth it,’ ” Neghumi remembered, speaking through a Spanish interpreter. WBUR agreed to use her nickname because of her immigration status.

With her husband and three children — ages 12, 6 and 4 — the family made its way to the U.S. But when they arrived, they learned the five of them couldn’t stay with family members as they had hoped. Although many new immigrants in Massachusetts qualify for the state-run family shelter system, the family didn't know they should apply.

Advertisement

Instead, a cousin connected them with an acquaintance who had space in her Chelsea apartment to rent. When Neghumi saw it, she said, she felt like running. For $550 a month, this person was offering half of a bedroom. The other half was rented to a father and son.

Neghumi said she felt her family of five had no choice. They slept there, all of them on one mattress that had lost most of its stuffing.

"It's become, ‘At least I have a roof. So it's OK if I don't have access to a bathroom. It's OK if I don't have access to a kitchen.' "

Norieliz DeJesus

Not allowed to talk

It wasn’t long before the atmosphere in the apartment grew tense.

Neghumi said the woman they were renting from, who was herself a renter, imposed strict rules on the family and particularly on Neghumi.

“I couldn't speak, I couldn't make noise,” she said. “I wasn't allowed to change in the bathroom. It was a struggle because I couldn't change in the room [because it was shared] or the bathroom.”

When Neghumi and her husband went to work, they reluctantly left their children with the woman renting them the room, who worked as a babysitter.

But soon, things got worse.

Neghumi’s 6-year-old started wetting himself, and her 12-year-old daughter was acting out. One day, Neghumi said her daughter confessed: The woman was leaving the youngsters home alone and forcing the 12-year-old to shoplift.

The daughter said the woman had threatened to call the police if she complained and report her mom for child abuse.

At a loss for where to go or what to do, Neghumi took her children to a nearby hospital, telling staff in the emergency room that her son had an upset stomach. She begged them to let the family stay overnight — she was scared to return to the apartment but didn't want her kids to be outside for hours in the dark.

“I just told them, ‘I just need the sunlight.’ ” Neghumi said through tears.

Her immigration status made her afraid to go to the police or even confide in hospital staff about her living situation, as did rumors the state might take her children away if they had nowhere safe to stay.

‘It’s really devastating’

“It's really horrible what we're seeing," said Norieliz DeJesus, director of policy and organizing at La Colaborativa, a social services nonprofit in Chelsea. "Our families are just like, in survival mode.”

DeJesus has worked closely with Neghumi’s family over the past year. After many tough months — including nights they did spend outdoors — she said, Neghumi and her family have found a place to stay where they feel safe. But DeJesus said subpar — and illegal — housing is increasingly common among people her organization is serving.

“It's become, ‘At least I have a roof. So it's OK if I don't have access to a bathroom. It's OK if I don't have access to a kitchen,” DeJesus said. “Conditions with mice, bedbugs and roaches — that's become a norm. So it's really devastating.”

DeJesus worries putting families on a waitlist when they need shelter will lead to more devastating situations.

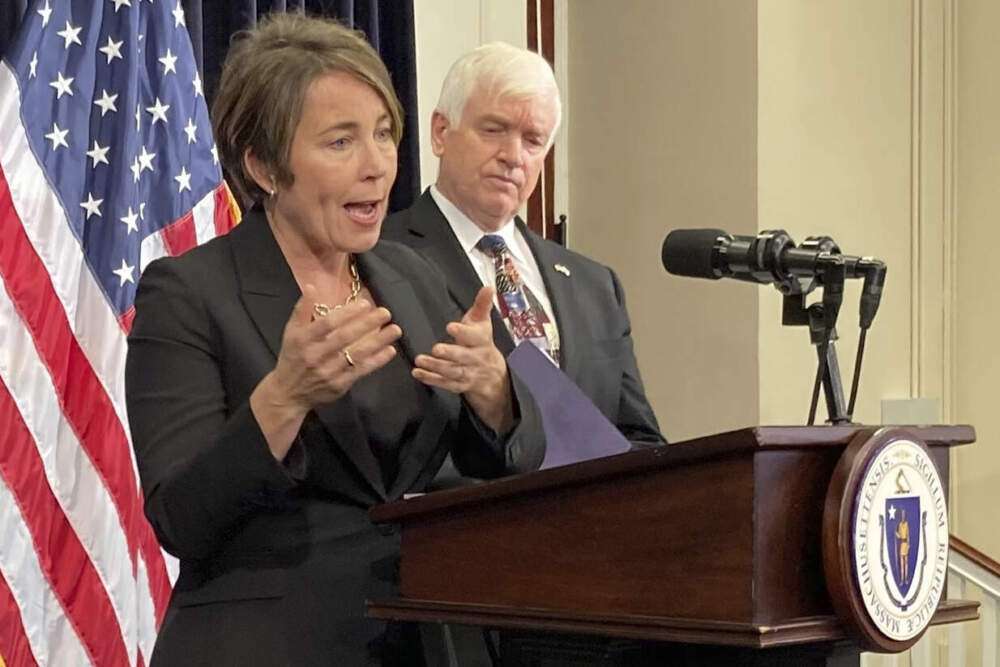

Speaking on WBUR's Radio Boston Tuesday, Gov. Maura Healey acknowledged those concerns.

“My heart aches for mums and dads out there, in particular who have kids, and they don't have a roof over their head,” Healey said. “But the fact of the matter remains, we're seeing an unprecedented capacity strain on personnel, on infrastructure and on funding.”

Healey said she is hoping the federal government will help.

Her administration requested assistance to set up large sites where families can stay while they are waiting for a shelter unit. In the past year, the program's population increased sharply. It is now more than twice the size it was at the start of last November.

Healey estimates roughly half the families in the system are migrants moving to the state. Officials say without capping the shelter program, its funding will be depleted before the new year.

While Neghumi and her family made it through those months of unsafe — or no — housing, there is still a lot of uncertainty about their future housing and their immigration status. Despite everything, Neghumi said her hope comes from her children.

When they come home from school with a little star because they are learning English, she thinks maybe there is good that will come from the suffering.

This article was originally published on October 31, 2023.

This segment aired on October 31, 2023.