Advertisement

'I landed on love': Families try a different approach to addiction

Close to one-third of American adults say they or someone in their family has been addicted to opioids, according to a recent survey. Ken Feldstein is among them.

When his son, Brendan, was in college, Ken learned from another parent that Brendan was using heroin.

"He called me at work one day to say, 'Kenny, I don't know if you know this, but Brendan is really struggling,'" he said.

The news floored him. Ken was in recovery himself from addiction to drugs as a teenager. He confronted Brendan, who admitted he was addicted to heroin.

"We both kind of in unison started weeping," said Brendan, now 38. "And Dad said we're going to get you help."

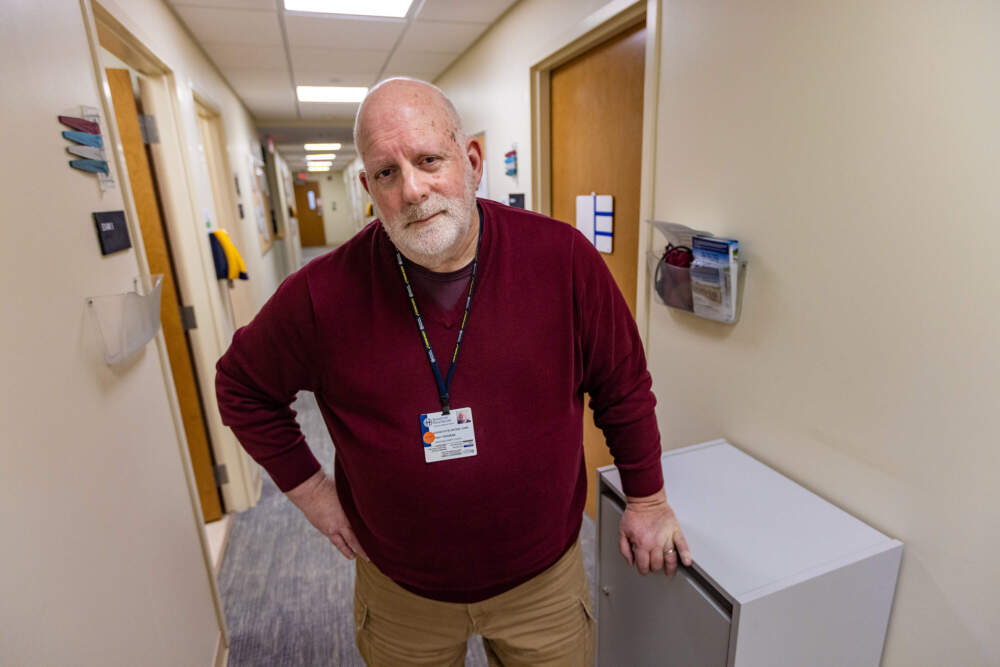

Ken knew from his own experience that treatment depends a lot on the person struggling. Now, as an addiction counselor, Ken argues there's another crucial — and often overlooked — factor. He believes loved ones can play an important role in guiding a person toward recovery. It's a lesson he learned from Brendan.

For several years, Brendan cycled through detoxes, treatment programs and sober living facilities. The family estimates he went through close to two dozen programs in all.

It was frustrating, Ken said, and he felt he had nowhere to turn for help. He found it difficult to talk to friends and neighbors about his son's struggles because "the stigma is so, so strong."

Ken and his now late wife Barbara turned to support groups for loved ones of people with substance use disorders. The meetings helped them find resources about treatment and how to talk with their other children about Brendan. The members of the groups understood what they were going through.

The main advice they got was to be tough — to not tolerate Brendan's drug use because that would enable it. Other parents told Ken and Barbara their children didn't get better until they refused to let them come home if they were using drugs.

Advertisement

"They said, 'You don't want to feel like it's your hand on the syringe that's going into their arm,'" Ken recalled. "So there's a really heavy message of, if you're tolerating it, you're playing a role in it."

Ken took what he calls "a big gulp of that Kool Aid" and told his son to leave the house.

"It sounded very reasonable because nothing we were doing was working," he explained.

After that, Brendan lived in his car and on the streets for several months.

Part of the allure of the drugs, Brendan said, was they helped him ignore the hole he had gotten into. His addiction began when he was prescribed opioid painkillers following an injury, he said. The physical addiction soon affected other aspects of his life. He dropped out of school, sold anything he had of value and worked odd jobs to pay for drugs.

Treatment programs did little to address the deeper problems, and he kept returning to drug use.

"I think I used the day I got out [of treatment]," he said.

Although family members of people with addiction are often told to let their loved one "hit bottom," Brendan points out that a person in throes of addiction can sink dangerously low.

"You might think you've hit bottom, but the basement has a trap door," Brendan said.

Memories from this period of his life are vague, but one moment stands out. It's the day he met his dad at a gas station.

"The moment I saw his eyes, something was different," Brendan said. "I'll never forget the look on his face, and it was just a mixture of love and sadness."

What Brendan saw was a shift. Ken had decided to parent his son through his illness. He wasn't going to punish Brendan or keep him away from the family anymore. Distancing himself from his son wasn't solving anything — or keeping Brendan safe.

"I landed on love. And I still feel that love wins."

Ken Feldstein

"He didn't get any better when we made the decision to not let him stay at the house," Ken said. "You could argue, 'Well, it's just as risky to enable them to use in the house,' So what do you do, you know?"

Ken's answer was to let Brendan be part of the family again.

"I landed on love," Ken said. "And I still feel that love wins."

Brendan didn't get better right away, but the shift offered a sort of new beginning for father and son. Then came another pivotal moment.

A few weeks after Brendan entered a new treatment program, his mom became very sick with cancer. Ken called to say she was in hospice care and wasn't expected to live much longer.

Brendan was adamant he wanted to visit his dying mother, even though it would mean losing his spot in the treatment program. Ken worried this could jeopardize his son's recovery.

Brendan felt anxious, too, about how he would handle such an emotional situation, but he went home to Norwell. He realized he was the only member of the family who could physically carry his mother to her bed.

"I ended up carrying my mother in my arms like a child," Brendan said. "It was a sort of a literal and figurative moment of strength for me, where my mother, who once carried me, I am now caring for her in these last moments — and I'm doing it sober."

Brendan and Ken both believe this experience cemented a strong connection to family and helped Brendan's recovery.

An increasing number of health care professionals are re-thinking the importance of connection with family and friends in addiction treatment. They point to research showing significant others and family members often play a critical role in helping people find a path to recovery. Yet, Alicia Ventura, with Boston Medical Center said families are often blamed for addiction.

"Nobody's bringing casseroles over to a family whose son has just overdosed because everyone has these wild views about it and what it means and the family's role in it," said Ventura, director of special projects and research for BMC's Grayken Center for Addiction Training and Technical Assistance.

Ventura runs BMC's trainings for addiction treatment professionals and families. She encourages loved ones to be more involved in treatment and receive more education about substance use disorders. She tells providers to listen to family members and avoid terms such as "co-dependent." The BMC program has trained thousands of addiction professionals around the country.

"I want to move us away from a historical and incorrect assumption that family members are the root cause of addiction or that they are responsible for perpetuating the disorder," Ventura told trainees in a recent session. "Instead, recognize the important role that family members and social support play in the lives of people with substance use disorder."

Her approach has critics. Some people who run support groups for loved ones point out that many families already carry a heavy load. They often take on the burden of navigating the treatment system and, in some cases, the legal system. They can face risks to their own physical and mental health from shouldering the ups and downs of addiction. They also point to people who say they stopped using drugs only because they faced tough consequences.

Still, with the deadly opioid fentanyl now permeating much of the drug supply and overdose deaths rising, Ventura and other addiction professionals argue other approaches to care are urgently needed.

"Enough people have lost enough people and think, if their person could just come back they would do things differently," said Maureen Cavanagh, a family recovery coach with Magnolia Recovery and Consulting Services. "People using drugs get better when they're loved and supported, and not when they're shunned aside. I think that's finally starting to sink in."

Brendan truly realized he had hit a turning point when he opened the refrigerator and found vials of his mother's liquid morphine. Not long before, those vials would have been the primary focus of his day. He picked one up.

"I was alone," Brendan said. "The stage was set for me to do what I always did and just check out. And I held it there for a bit."

But he put the vial back.

"I decided in that moment, not again, never again, not doing it anymore," he said. "It's time to step up and contribute, and give this family a reason to hang on."

He hasn't used drugs in almost a decade since.

Brendan credits his family's shift toward acceptance and a strong 12-step program for his success. The key, Brendan said, was knowing someone cared about him, even when he didn't care much about himself.

His dad Ken rejects the idea that treatment should be "tough love" versus family support. He believes families can determine what works best for them and the person struggling. His son got better for a variety of reasons, he said, but being included in the family was a significant factor. He sees recovery as a long, complex, individual process.

"Love takes many, many forms," Ken said, "'Tough love' still has the word 'love' in it. So, I think it's just leveraging what comes naturally to families, which is to be there for their loved ones."

This segment aired on November 20, 2023.