Advertisement

A grand vision, with few specifics, for the overhaul of Boston Public Schools buildings

Boston Public Schools officials shared their long-awaited “master plan” for school facilities Wednesday, after narrowly meeting a deadline set by state education officials.

The plan is presented as an opportunity to address long-standing problems with Boston school facilities, including under-enrolled schools, deferred maintenance and, generally, inadequate spaces for working and learning for students and staff.

And it imagines a future of larger, newer, greener — and fewer — standalone schools as it seeks to address present-day problems. The 80-page plan suggests that, at the very least, a little more than a dozen district schools eventually should merge or close.

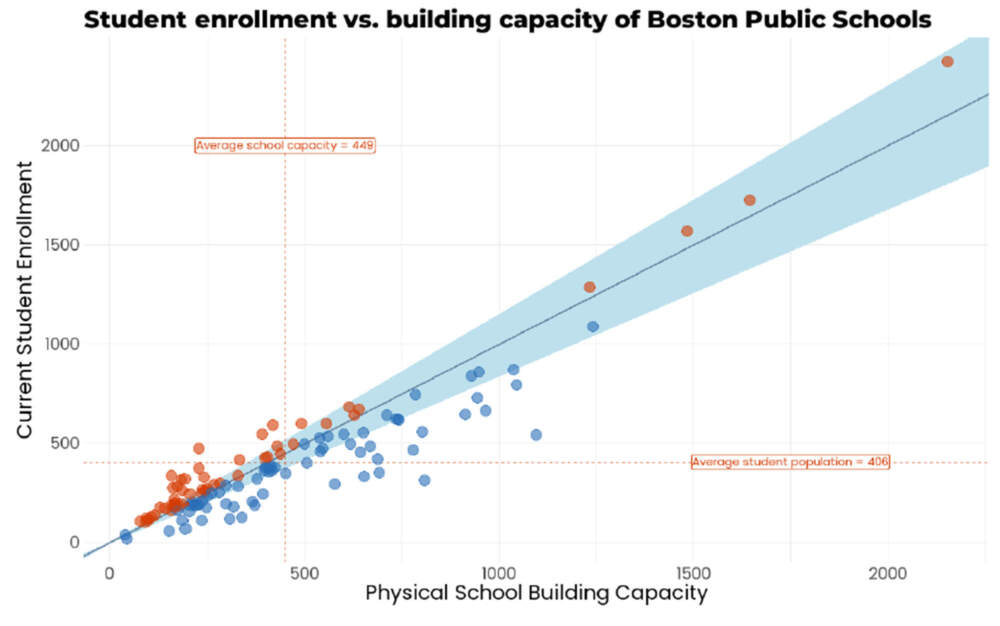

Of the 119 school buildings citywide, the report finds that dozens are “underutilized,” or well-below capacity, after years of sliding enrollment. According to district data, just 18% of them are equipped to provide what it calls a “high-quality student experience.”

For example, the district has long argued that its many small, single-strand elementary schools — with just one class per grade — can severely hinder enrichment opportunities and administrators’ ability to best serve students with disabilities or those who are learning English.

While past facilities plans — like former Mayor Marty Walsh’s “BuildBPS” announcement in 2018 — stalled or sparked protest, Jessica Tang, president of the Boston Teachers Union, is cautiously optimistic this time around.

Tang said the past few years laid bare how “completely inadequate” the district’s buildings have become. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Tang said, officials found that “many schools not only did not have proper [ventilation], but didn’t have working windows.”

Tang — who had seen the plan in advance of its publication — described it as a good “first step” toward redressing historic disinvestment in Boston’s schools, though it invites questions about the implementation.

The new master plan was the last promised deliverable in the city’s 2022 deal with state education officials that staved off a state takeover. The final version of the document was sent to DESE on Dec. 29, according to a district spokesperson — just three days before the agreed-upon year-end deadline.

The plan is anchored in an uncontroversial idea: that BPS’s buildings aren’t serving current students, with many missing technology hubs, auditoriums, science labs and art spaces.

Indeed, the district has shrunk dramatically since its 1970 peak enrollment of around 96,000 students. Enrollment has continued to slide in the past decade: in 2013, BPS enrolled over 54,000 students, while this fall, the count has dropped below 46,000.

Meanwhile, “the number of BPS schools has remained relatively unchanged, resulting in under-enrolled schools and district resources stretched too thin across too many school communities,” the plan states.

Tang says her staff have counted in the neighborhood of 30 school closures since 1994.

But Tang did credit officials for outlining a more transparent public process than the one used in the past ahead of the closure of the Mattahunt School in 2016 and of the West Roxbury Education Complex in 2018.

The plan does not include specific recommendations about the future of each of BPS's 119 school buildings. It serves instead as a procedural framework for how the district will inform families, design solutions and enact them, as Mayor Michelle Wu said on a Dec. 18 appearance on WBUR's Radio Boston.

District officials imagine a standardized, 18-month process before approving the merger, closure or renovation of a school.

“These [steps] are disruptive and can be daunting — but it’s clear that the status quo is not working for Boston’s students,” the report states.

Historically, though, it’s been the details that have sparked pushback and deepening mistrust among the public — most recently with plans to move the John D. O’Bryant School from outside Nubian Square to a renovated site seven miles away in West Roxbury.

And while it lacks specific timetables, the framework does suggest that many BPS schools will eventually need to close or be consolidated, given enrollment patterns.

It suggests the city should move from 87 elementary schools down to at least 80 — and as few as 40. When it comes to the 31 secondary schools, officials envision a decrease to between 19 and 24.

In the most extreme case, that would mean the closure or merger of some 60 schools — about half of the total — causing widespread disruption for BPS families.

Then again, those ranges also leave room for a more modest overall impact. At minimum, BPS proposes the reduction, closure or consolidation of 14 schools — or roughly 12% of the current total.

In late December, WBUR requested additional data about the names of under-enrolled schools, as well as those that no longer meet BPS’s definition of “high quality.”

Past details, next steps

Many of the details included in the master facilities plan have been part of the city's public record for months.

One of the major components, the "Facilities Conditions Assessment," was released in mid-October.

That assessment scored the district's buildings based on a number of factors, including how many students a building can accommodate, its energy efficiency and whether it meets modern standards of school design.

BPS leaders also released a preliminary "decision-making rubric" at a mid-November school committee meeting. That rubric laid out factors that district officials will consider when making big facilities decisions — such as needs of the local neighborhood, the building's current condition, and what size school building the land can accommodate.

The rubric also included information about the four new "building school models" BPS leaders plan to use, which breaks elementary and high schools down into two categories — small and large.

The state’s board of elementary and secondary education is expected to discuss its oversight of BPS more generally at its next meeting later this month.

BPS officials present the new plan as the product of continual community feedback: officials say it reflects the thoughts of more than 500 community members, and add more than 9,000 responded to a May 2023 survey.

Some building projects are already underway. BPS still plans to merge the Shaw and Taylor elementary schools in Dorchester into a single pre-K-6 school by fall 2024. Meanwhile, city officials last summer announced the O'Bryant move.

There’s little new information on those proposals in this latest document — but district officials said they expect a school committee vote on the O’Bryant proposal in late spring.