Advertisement

Seiji Ozawa, the Red Sox-loving maestro who led the BSO for 29 years, has died

Resume

Seiji Ozawa, the unconventional maestro who led the Boston Symphony Orchestra longer than any other music director, has died of heart failure at the age of 88. The Japanese conductor will be remembered for breaking barriers, courting controversy and loving a certain Boston baseball team throughout his career.

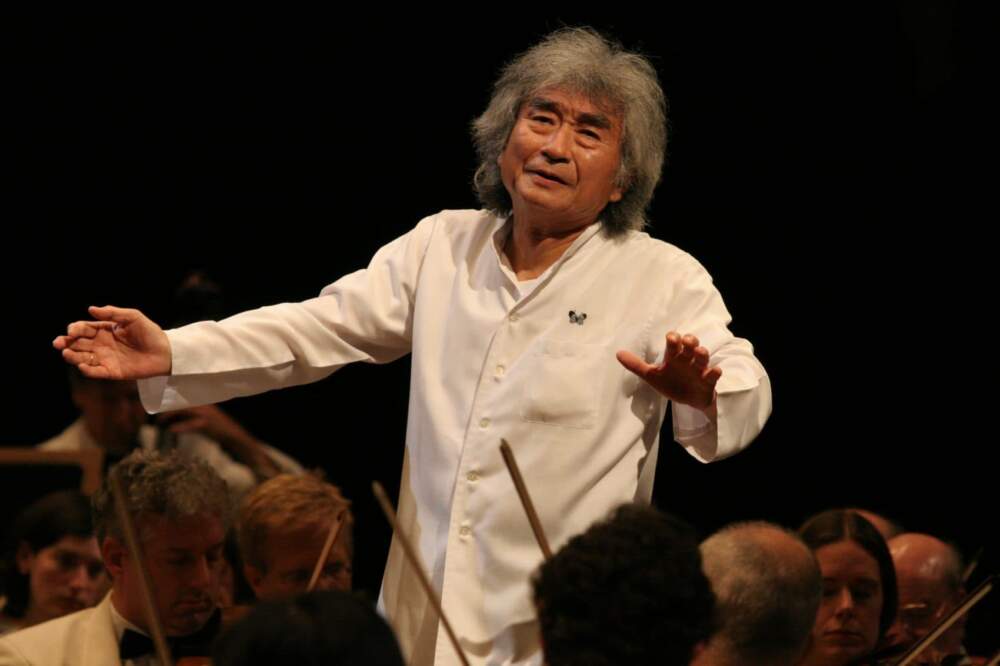

When Ozawa arrived to lead the BSO in 1973, he struck a strikingly different pose than his predecessors. Longtime classical music critic Ellen Pfeifer remembers how the spritely, 38-year-old conductor opted to wear a tunic at the podium, not the usual tux. He also had a moppish head of hair, and often wore hippie-style love beads around his neck. “He was very much a product of that era,” Pfeifer recalled with a laugh.

Ozawa stood out in other ways. Pfeifer had just started writing for the Boston Globe and his new post was one of her first assignments. “I was asked to call some of the Boston Symphony subscribers and ask them what they thought about a Japanese conductor being appointed music director,” she said.

Before Ozawa, the BSO’s music directors had names like Steinberg, Leinsdorf, Munch, and Koussevitsky. Pfiefer said choosing a 30-something Asian musician was a bold move for the orchestra’s leadership, and added, “They went out on a limb.”

Ozawa’s hire would pave the way for other Asian musicians to cross into a genre dominated for centuries by white men. This cultural sea change wasn’t lost on the maestro either, as he told NPR in 2002. “Since I’m kind of pioneer,” he said, “I must do my best before I die so people younger than me think: 'oh, that is possible.'”

Ozawa was born in the People’s Republic of China in 1935, and spent his early childhood in Japanese-occupied Manchuria. When he was 9 years old, his parents returned to Japan where the family struggled through the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

As a youth, Ozawa was fascinated by Western classical music. His father was a rural dentist who — as the story goes — pulled a piano 25 miles in a wagon so his son could have an instrument. But, as a teenager, Ozawa sprained a finger playing rugby. His music teacher Noboru Toyomasu suggested he consider a different path: conducting.

In our 2015 interview at Symphony Hall, Ozawa recollected how his younger self had never before seen an orchestra or conductor in action. "There was no television yet,” he told me, “And it’s funny — I went to a concert for [the] first time in my life. A Japanese orchestra played Beethoven No. 5 Piano Concerto."

That first concert blew Ozawa’s mind. When the Symphony of the Air performed in Japan, Ozawa said his eyes and ears opened even more. "It was a completely different sound," he remembered. "So I told myself I must go out of this country, Japan, to be with this kind of sound."

With his teacher’s help, Ozawa made his way to France. In the 1950s, he won an international competition, which caught the attention of then-BSO music director Charles Munch. He invited Ozawa to be a fellow at the prestigious Berkshire Music Center in Massachusetts, which is now called the Tanglewood Music Center.

Then the charismatic composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein took notice. He hired Ozawa to be his assistant at the New York Philharmonic. The rising artist’s course continued to surge forward. After stints in Japan, Toronto and San Francisco, the BSO — one of the world's "Big Five" orchestras — offered Ozawa its music director position in 1973. The conductor stayed with the organization for a record-breaking 29 years. "I was very lucky," Ozawa said of his trajectory when we spoke in 2015.

As a conductor, Ozawa exhibited a few notable quirks. He could be heard grunting at the podium. He led massive scores, including Mahler Symphony No. 8, from memory. Ozawa did not use a baton, and he had his own way of moving onstage.

“What a dancer he was,” retired BSO trombonist Norman Bolter recalled. “But not only just as a dancer getting up there and doing his own jig.”

Bolter knows this well because he performed paces away from Ozawa for more than 20 years. “His clarity in conducting was extraordinary,” Bolter said. “It had a fluidity, it had a ballet aspect to it, and it was alive.”

The maestro hired Bolter in 1975, when the trombonist was just 20 years old. Now teaching at the Boston Conservatory at Berklee, Bolter’s feelings for Ozawa are nostalgic and personal. He said he’ll never forget the long conversations they once had and the conductor’s intensity. “His eyes could penetrate right through you,” Bolter shared. “You could feel him assessing you.”

For the trombonist, Ozawa’s grasp of certain composers was profound. “Seiji did Bartók — in my mind — like nobody did,” he said, adding, “the maestro let the orchestra play, he wasn’t a control freak in that way.”

Ozawa also displayed a much less serious side. In 1988, he led a muppet-populated “All-Animal Orchestra” on Sesame Street.

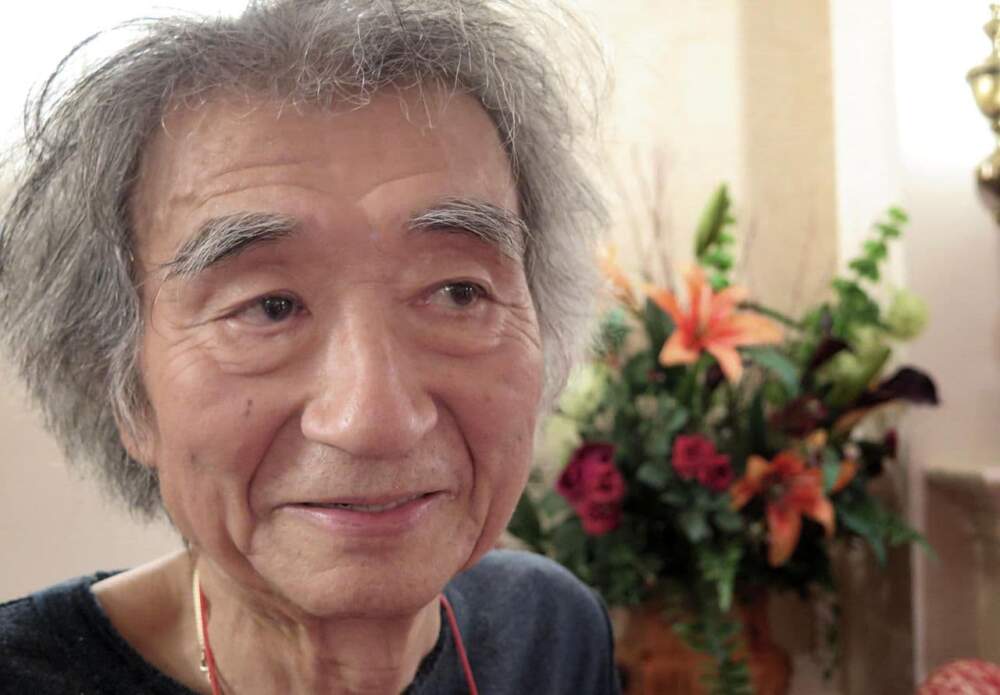

The Japanese maestro was recognized for his contributions to American culture with a Kennedy Center Honor in 2015. During our interview for a story about Ozawa's award, Hollywood film composer John Williams called his fellow BSO alum “a beacon” lighting the way for Eastern musicians to head west. “We have a lot of younger virtuosi coming now, especially from China,” Williams said. “But in Seiji’s generation, he was alone in that so he was certainly a pioneer.”

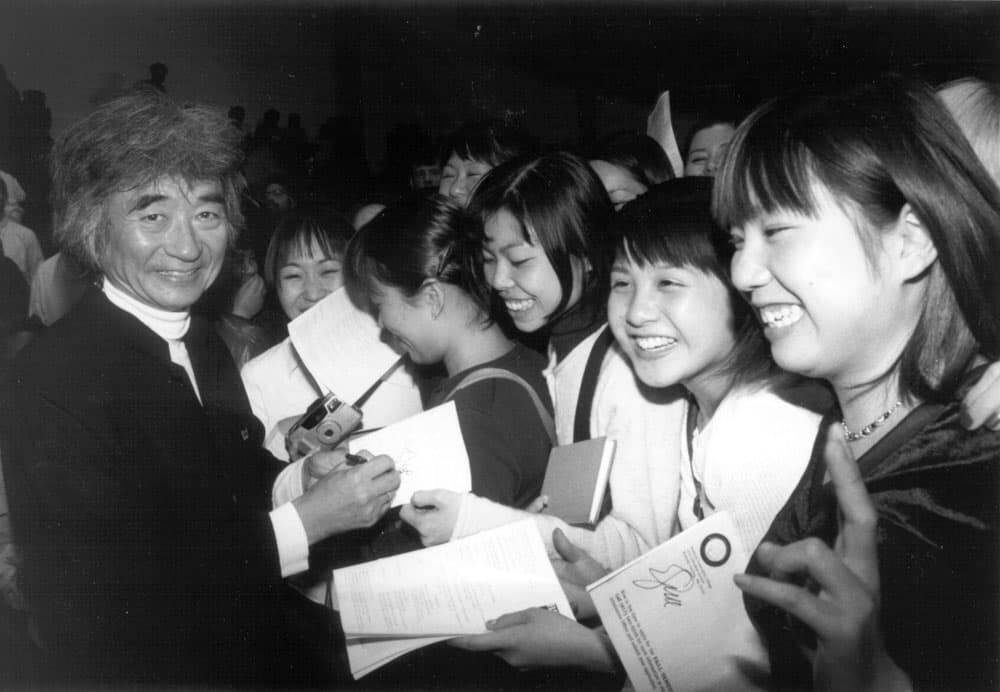

In Japan, Ozawa has long been revered as a celebrity. But it wasn’t always that way. After he left his homeland, some people there felt he’d become too westernized.

When asked about Ozawa during the BSO’s tour of Japan in 2017, music critic Hiroo Tojo elaborated, saying this was especially true for the veteran reviewers. “They had a lot to say about Seiji because he was extremely different,” Tojo explained through an interpreter. “So the older generation of critics really did not like that. But the younger generation critics welcomed his presence.”

Tojo covered Ozawa’s career for decades and called the conductor “a superstar that Japan created.” When the BSO broke the European conductor mold by hiring him, it also carried weighty symbolic meaning in a country devastated by its role in World War II, its surrender to Allied forces, and the dark, emotional shadow that endured in the aftermath. “It almost erased all of that because it was such a significant thing for a Japanese conductor to become a music director in the United States,” Tojo said.

During his tenure with the BSO, Ozawa also courted controversies, perhaps most notably in the 1990s at the Tanglewood Music Center in the Berkshires. A string of controversial hires and fires enraged some of the orchestra’s longtime administrators and musicians, leading to resignations, bad press and a precipitous drop in morale.

“His legacy of handling personnel issues I don’t think was always, um, ideal,” Pfiefer recalled. Even so, she said Ozawa changed the face of the orchestra. She also called him a musical ambassador for taking the BSO to China in 1979. It became the first U.S. cultural organization to do so after diplomatic relations with the country were normalized.

Over the years, Ozawa made it his mission to foster a deeper appreciation for western classical in his home country of Japan. He’s known for co-founding the Saito Kinen Orchestra in 1984, which was named for Hideo Saito, his former teacher at the Toho School. Eight years later, Ozawa created an annual festival for that orchestra in the city of Matsumoto. He also founded the Seiji Ozawa Music Academy in 2000 with the goal of promoting opera and nurturing young musicians.

In 2001, the Japanese government named Ozawa a Person of Cultural Merit. A year later he left the BSO to lead the Vienna State Opera. He stepped down from that position in 2010, the same year he was diagnosed with early-stage esophageal cancer.

Ozawa continued engaging in classical music-making for years as he battled the disease’s effects. In Boston, before he became too frail, the maestro’s fans were still able to see him — but not at the podium. Seiji Ozawa loved going to Fenway Park so he could root for his favorite baseball team, the Boston Red Sox.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly referred to Symphony of the Air's affiliation with the BBC. The symphony was comprised of former NBC Symphony Orchestra members. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on February 09, 2024.