Advertisement

'I'm Going In': How Sportswriter Diane K. Shah Opened Doors

In July of 1971, Diane K. Shah arrived in Detroit for the MLB All-Star Game. As far as she knew, she was the first female sportswriter ever to cover that event.

She checked into her hotel and picked up her credentials. And she was handed a goody bag.

"And it was all men's stuff, you know, razor blades, razors, tie clips," Diane says. "I thought it was kind of funny. But anyway, there was this envelope. And I opened it up, and it said there would be a dinner that night at six o'clock for sportswriters and baseball players. And I thought, 'Oh, great. Saved. I don't have to eat in my room.' "

So, a few minutes after 6 p.m., Diane went down to the ballroom.

"Most of the tables were still pretty empty," Diane says. "But as I stepped in, this man blocked me, and he said, 'I'm sorry. Where are you — where are you going?' I said, 'I'm going in here for the baseball writers dinner.' And he said, 'No, women aren't allowed. You must be in the wrong place. I said, 'No, I'm in the right place.'

"You're not going to win every time. ... But I think you can win a lot more than you think you can."

Diane K. Shah

"So we began this little battle. And he was determined to keep me out. He said, 'It's a stag event.' And I said, 'OK.' And I said, 'Tell me. Are there going to be naked women jumping out of cakes? Are they going to tell dirty jokes?' And he got all upset. 'No, no, of course not. It's just ...'

"So meanwhile, all these men were allowed to just walk in. And I started to turn away to go back up to my room. And all of a sudden this voice — I don't know where it came from. It came from me. But I just found myself saying to him, 'Well, I'm going in. You will have to bodily remove me.' And I walked in the room. And I expected somebody, him or somebody else, to yank my arm and pull me out. But nobody did."

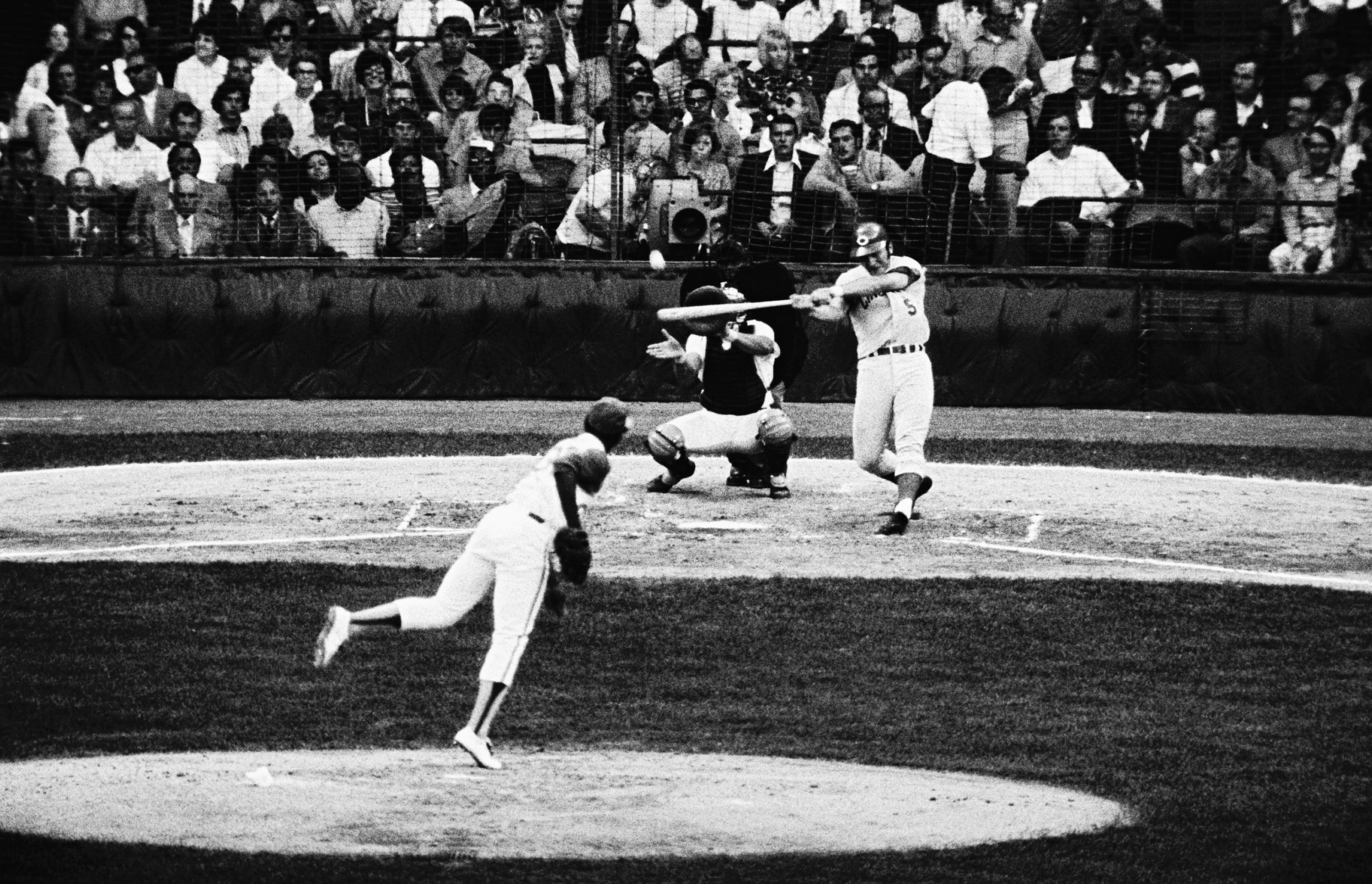

Diane stopped at the first table she came to. It was empty except for Cincinnati Reds catcher and future Baseball Hall of Famer Johnny Bench.

"I’d met him a couple times," Diane says. "And I said, 'Hi, Johnny, do you remember me? Can I join you?' And he said, 'Of course, sit down.' So I did.

Advertisement

"It turned out to be a very boring dinner. It wasn't worth the trouble I'd gone through to even get in. Bobby Goldsboro, the singer, country singer was Johnny's guest. And then there were two other sportswriters. And when the dinner ended, Johnny Bench said, 'Hey, you know, I've got beer up in my room, why don’t y'all come on up?' So we did."

When her All-Star game report appeared in the National Observer a few days later, Diane started by setting the scene in Johnny Bench’s hotel room the night before the game:

Goldsboro wound up in a dark corner, strumming his guitar as accompaniment for, who else? Bench.'When you’re hot, you’re hot. When you’re not, you're not,' bellowed the catcher, who wouldn’t know what it’s like to be 'not.'

"And that was one of my first instances of like, did I break down a barrier? I don't know what I did, but I did get in," Diane says.

KG: Would I be wrong to see this as sort of a theme of your life — pushing your way through doors that are not exactly open to you?

DS: I never thought of it that way. But you could be right, especially when it came to reporting. I always somehow tried to find a way to get what I needed. My first — I had a summer job at a newspaper. And I would sit there with my hand on the phone for 10 minutes before I could pick it up and make a phone call. But, when you're a reporter, you're on deadline. You have to produce the story, and you have competition. And you don't want them to have a better story. So I think that makes you do things that in ordinary life you wouldn't.

KG: OK, so let's skip to the fall of 1972. The Boston Red Sox were in a race for the pennant. And you were accused of "destroying the American family." Explain, please.

DS: Yes, one of my worst failed attempts. I don't think I succeeded there. But, yes, I was working for the National Observer newspaper, a weekly paper published by Dow Jones.

A few years earlier, Diane had been one of the first female journalists ever hired by Dow Jones. She wasn’t a full-time sports writer. She covered everything from the Republican National Convention to New York Fashion Week. And the paper allowed her to write about sports — a life long passion — whenever she wanted.

So, in the fall of 1972, Diane called the Red Sox to request credentials to six home games. She says she spoke with a man named Bill Crowley — she would call him "Super Flack" in her story — who told her that the Red Sox didn’t allow women into the press box. Or on the field. Or into the dugout.

DS: In fact, Crowley had told me, he said, "You know, we let one girl in here, and it was a disaster." Turned out this reporter from the Waukegan New Sun had been in the press box, and a foul ball had hit her on the shoulder. I mean, I don't think that was her fault, but that was a disaster. They didn't want to have another disaster.

Diane was persistent. And at the end of the week, just two hours before gametime, she was granted access. Diane was on the field for batting practice when she was pulled away by Crowley’s assistant — who insisted on giving her a tour of Fenway Park.

DS: Basically to get me away from the players. So we go up to the roof. You probably know this, Karen, that — unless they've changed it — but that's where the press lounge was. And he took me up there. Right outside the door to go in was a wrought iron table with one place setting and a sign that said "Ladies' Pavilion." And he said, "You can have dinner here." I said, "I don't think I'm hungry. Thank you." And then he opened the door to the press lounge, and he said, "You can't go in here, except" — and he pointed down down the hall to a door with a sign that said, "Ladies" — he said, "You can use the bathroom. That's all." I said, "Oh, OK."

Finally, Diane was led into the press box where she was seated near Bill Crowley — aka Super Flack — who spent the first few innings ignoring her.

"Finally, I introduced myself," Diane says. "And he said, 'See what you've done. Tomorrow there'll be 50 girls here saying that they're reporters.' And I said, 'Well, I don't think there's 50 female sports writers in the country, sir.' And he said, 'No, but they'll say they are just to get to my boys.' And then, a little while later, he said to me that I was probably going to destroy the American family."

In her memoir, Diane wrote:

By week’s end, they had all pretty much come around. When I didn’t show up for one game (I was sitting in the stands with my husband), Super Flack actually remarked, "Where is that girl? She’s been good luck. Get her up here."

Perhaps the American family will survive after all.

DS: Probably every profession, it's the same situation. It's just, 'Hey, we've never had women around here before. We don't know what to do with you.' But, somehow, I don't know, I always thought it was funny. I didn't take it too seriously, because all I really wanted was to get my story. And as long as I could get my story, you know, I didn't care."

KG: In 1981, you took a job with the Los Angeles Herald Examiner and became the first female sports columnist for a daily paper. Or at least that's what they said. So I don't want to imply that it was only men who didn't know what to do with you. Tell me about Georgia Frontiere, the majority owner of the Rams from 1979 to 2008.

DS: Ah, yes, Georgia. Georgia became owner of the then-Los Angeles Rams when her husband, Carroll Rosenbloom, drowned.

When Diane took the job in LA, she was welcomed into the Dodgers clubhouse and the Lakers locker room. But when she called and requested access to the Rams, Georgia said, "No."

DS: I don't remember that I told my editor. I mean, I just figured, "OK, I'll get what I need. I'll figure it out somehow." So that Friday night, I was at the Lakers game — it was before the game started. I got a phone call from the editor of the Herald Examiner, and he said, "Oh, by the way, we just sued the Rams on your behalf. I'm putting a reporter on the phone to interview you. It's going to be page one tomorrow." And I was really upset, because I didn't want to be involved in a lawsuit. I didn't think it would be helpful. And I kind of prided myself at that point, on figuring out how to solve my own problems.

The next day, during an emergency court hearing, the Rams declared that all reporters — both male and female — would be barred from the locker room. Instead, players would be brought into a separate interview room.

When Diane arrived at the stadium the next day, it was clear that some of her fellow sportswriters weren’t happy with this new arrangement.

DS: Anyway, the game ends and we're shepherded down into the bowels of the stadium, into this concrete room with folding chairs. And at the back of the room are two aluminum tables covered with white table cloth. And on these tables are bottles of liquor and wine, some soft drinks, beer, and two bartenders. So the reporters walk in. And they see this, and they go, "What? Are you kidding me? We're on deadline. We're not partying." So all the anger towards me now went back to Georgia. They were furious with her. It was an insult.

KG: My favorite story of you opening doors that were not supposed to be open to you has nothing at all to do with your gender. The year was 1985. And the door in question was the door to the White House. Tell me that story.

DS: Yes. So what happened was the Lakers had finally beat the Celtics for the NBA championship up in Boston.

President Reagan invited the team to the White House, and Diane and the rest of the writers tagged along. But, when they got to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, a guard met the writers at the bus and told them their names weren’t on the list and they wouldn’t be allowed in.

DS: So some of the reporters jump off the bus. They said, "Oh, no, we're here for the Lakers." And he said, "No, I don't have your name." I got off the bus, too. And I had covered things at the White House years before, and I knew there were two entrances on Pennsylvania Avenue. So I take off. I run to the other one. And there's a guard there. And, before he can stop me, I just ran right past him. I held up my press pass. "I'm with the Lakers," I said. And I kept running. So I'm wandering around the White House looking for the Lakers. And I finally found them, and I wrote a story. Nobody else wrote that story, because nobody else figured out how to get in.

KG: Is there a lesson that you take from all the doors you've broken down?

DS: Yes. And I don't want anybody to take this wrong, but we all have problems. I don't care what job you have, or even if you don't have a job. Problems come with life. And I always thought if you could figure out your own way to solve your own problem — I found that when I did solve my own problems, it empowered me. It gave me such a great feeling that, hey, I did this. I did it myself. I didn't sue anybody — except that one time when my paper did.

And I think that that's something that's super important, to be able to know: You're not going to win every time. No. But I think you can win a lot more than you think you can.

Diane K. Shah is the author of "A Farewell to Arms, Legs and Jockstraps: A Sportswriter's Memoir."

This segment aired on July 25, 2020.