Advertisement

'Somebody's Going To Listen': Opioid Watchdogs Fight Epidemic With Letter Drops, Grassroots Action

They arrived in our mailbox, almost all at once. A waterfall of paper:

We opened the letters and found stories of children, siblings, parents and lovers. Each once so full of life. Each dead of an opioid overdose.

"People keep seeing this stuff on TV, but nothing is getting done, really," Tim Kramer tells On Point. "We took it upon ourselves. We’re all grieving, so we’re going to do it. We’re going to make a change."

Kramer manages the Opioid Watchdogs Letter Drops, a nascent grassroots campaign that began three months ago. Members in at least 30 states and Puerto Rico pick a day, pick a media outlet and fill that outlet’s mailbox with letters telling the stories of loved ones lost to the opioid epidemic.

The effort is an offshoot of a larger group: Purdue Watchdogs, an online network of family members, advocates and some doctors and nurses who share resources and advice, and plan public events.

The goal is "to build a national coalition, supporting prevention efforts and assisting advocates fighting the epidemic in individual states and territories of the USA," says Purdue Watchdogs founder Carol Egan, 66, of Savannah, Georgia. "[The group] is asking every American to [put] the epidemic first."

Advertisement

As the opioid addiction crisis rages on, Egan believes there’s a significant need for states that have more experience with the epidemic to share information, advice and resources with states where the death tolls began rising more recently. Members provide each other with test strips for the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl, compare notes on how to lobby state houses to take action and organize public actions.

They also write letters.

'My Addict Paid With Her Life'

Tim Kramer’s letter arrived from Waterford, Michigan. LeeRae Conn was his partner for almost a decade.

"I don’t know what originally got her hooked on it because I met her nine years ago, and when I met her she was already hooked on it," Kramer tells On Point. "I didn’t realize that. I thought she had narcolepsy."

Conn was on a cocktail of at least five different drugs, all prescribed by the same physician, Kramer says. She would frequently nod out. He says the first night he saved Conn’s life, he found her passed out in the bathtub.

Conn went into rehab. She also moved on to another doctor. Kramer wrote in his letter:

Conn died on June 29, 2018.

"I see the ultimate goal as making doctors accountable," Kramer says of the letter drops. "Pain management — that’s all that is, is a license to give people pills. ... They need to know who their patients are. They need to know that a lot of their patients are addicts."

'Getting Stronger By The Minute'

Egan, the Purdue Watchdogs founder, ran drug counseling coalitions in Morris County, New Jersey, for 30 years. "I know how to deal with people who are around this disease, who have had this disease, who have lost people to this disease. I started to work with these people, and they’re getting stronger by the minute," Egan says. "Tim [Kramer] got so strong overnight, and he was crushed when I first started talking to him. He is a leader in this now, and that was only like eight months ago. You can’t believe — once you give them the tools and the path — what they’re going to do."

She’s witnessed effective action before. In the mid-1980s, Egan brought together parents whose families had suffered as a result of a surge of cocaine addiction in the area. They formed a municipal activist group that fought for grant money and prevention services. Egan says their advocacy helped lead to the installation of drug counselors at every high school in New Jersey.

Egan eventually retired to Georgia. In 2018, she heard of a public art installation that featured an 800-pound steel sculpture of a heroin spoon in front of Purdue Pharma headquarters in Stamford, Connecticut. Purdue is the maker of the popular opioid painkiller OxyContin.

There are more than 1,600 lawsuits currently pending against Purdue Pharma. One of the most recent cases against the company and its owners, the Sackler family, comes from Massachusetts.

Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey alleges that members of the Sackler family personally and directly pushed sales reps to mislead doctors, steer patients to higher dosages and pocket billions in profits.

In a recent statement, Purdue called the complaint a baseless "vilification" of the Sacklers. The company is asking a court to throw out the lawsuit.

In March, Purdue reached a $270 million settlement in a similar lawsuit filed by the state of Oklahoma.

But some advocates are furious about the settlement.

“[It's] a huge disservice to the tens of thousands of families here in the United States who have buried a child,” Cheryl Juaire, of Marlborough, Massachusetts, told NBC News. Juaire's 23-year-old son died of an overdose in 2011, and she founded Team Sharing, a nonprofit support group for parents. Egan says Juaire’s work also inspired her to create Purdue Watchdogs.

Jauire had planned on traveling to Oklahoma if the Purdue suit had gone to trial. Hundreds of mothers intended to stand outside the courtroom holding photos of their dead children. The settlement is "blood money from our children," Juaire said.

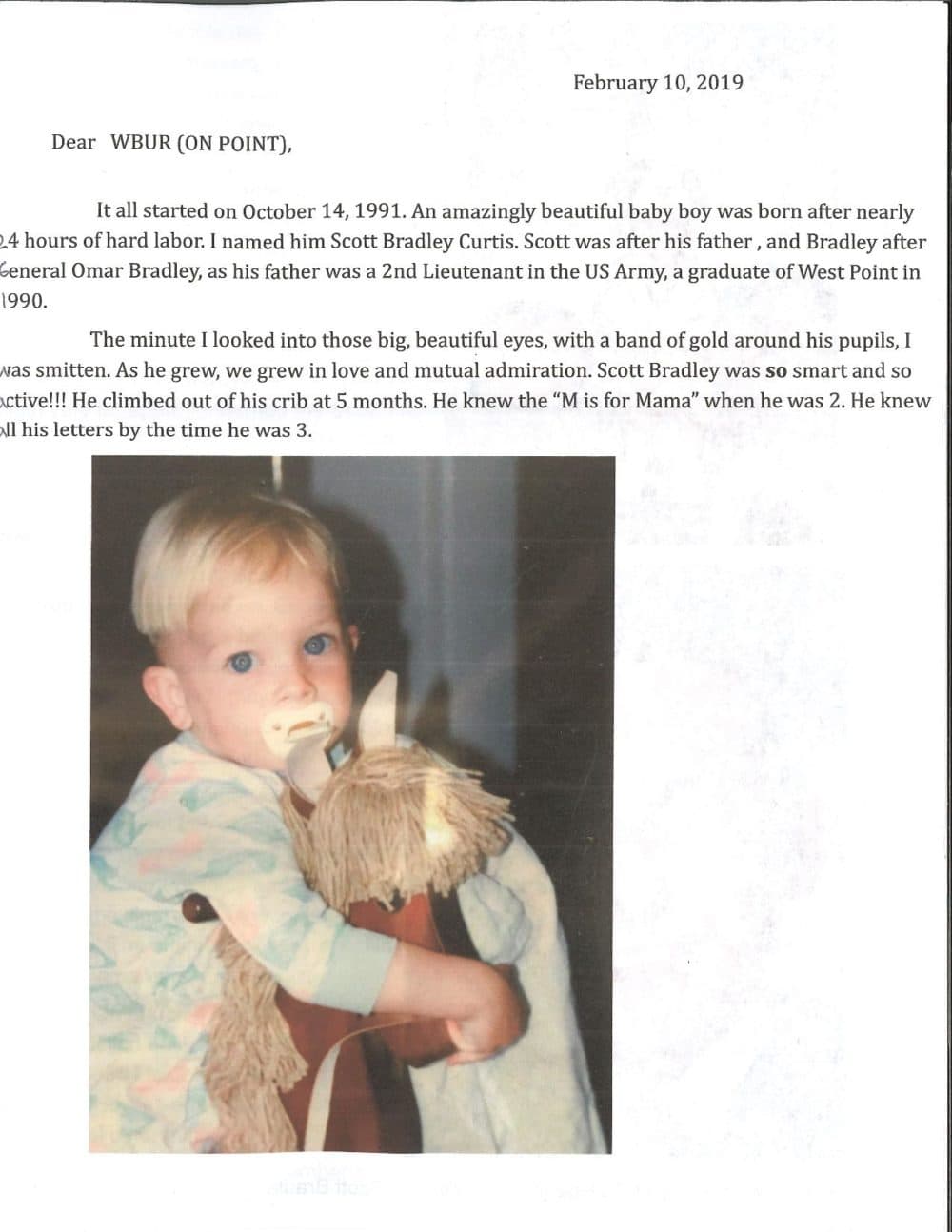

'How Can The Beautiful Boy With The Most Beautiful Eyes Be DEAD?'

Those words float on the page above a large color photo of a little boy sitting on a rocking horse. Scott Bradley is cuddling a blanket, his deep blue eyes gazing into the camera. His mother, Susan Seeley, of Bishopville, South Carolina, writes in her letter to us that her son got hooked on oxycodone after a car crash. A friend later suggested he try heroin because "it’s a lot cheaper." He lost his job and resorted to selling drugs. Seeley writes:

"He lied ALL THE TIME ... He could tell me the sky was blue, and I’d go out to check to see if it was suddenly green. I love my son, I’ve always loved him. I always melted in his eyes. But, the glimpses of the real Scott Bradley were often very far apart."

Bradley’s life went up and down, Seeley writes. He got married and had a child.

The Scott Bradley I knew and loved seemed to be coming back! But later he got arrested for fraud. Honestly, it was good ... He was clean. But he got out, and soon, was lost again. September 2018, Scott Bradley died of an overdose.

Seeley’s letter screams with the agony of a mother who was alone and unsupported when she found out her son had died of a fentanyl overdose. The Purdue Watchdogs seek to bring people together to channel their pain, anger and frustration into action.

Egan points to other family advocates doing similar work, such as Mary Peckham in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, who lost her son Matthew to a heroin overdose in 2012.

"The police in her county, they go to the home 24 hours after an overdose with a trained recovery coach and a social worker and plainclothes policeman, and they follow up and coax the person into treatment if they can," Egan says. "A lot of the moms are recovery coaches. This program is one of the most successful. It’s being copied all over the country with the police, making the police the good guy."

This support team will also follow up with families in the event of an opioid death, too, according to Egan. "Can you imagine if you lost your child and then you’re going to comfort another mother? And the police are with you?"

'How Are WE Going To STOP This Epidemic?'

Paige’s mother, Elizabeth Mazurek of Stanwood, Michigan, uses letterhead with a winged heart and the words "Paige’s Promise" at the top of the paper. Mazurek writes that Paige was 17 when she got addicted to opioids after a dental procedure. Three years later, she was addicted to heroin. She was 22 when she died in 2015.

"How are WE going to STOP this epidemic?" Mazurek asks. She writes that Paige was one of 15 people who died in the suburbs of Oakland County that week. Mazurek says her daughter’s death certificate doesn’t state a specific cause of death.

"Paige’s case was closed and who knows how many more her dealer killed."

But Mazurek adds that there are 400,000 faces to put to the epidemic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that between 1999 and 2017, almost 400,000 people died from overdoses involving any opioid, including prescription and illicit compounds. That’s why Mazurek says she joined Purdue Watchdogs.

Egan says it’s these loved ones who are "fighting like crazy on the front lines" and "walking beside one another so that no one has to endure this loss alone."

On April 12, dozens of parents whose children fatally overdosed met up at Harvard University to demand the removal of the Sackler name from a building that houses one of the school's art museums.

"The beauty of all of this is connecting the doers in each state to each other and having them teach what works, what hasn’t worked, how to talk to legislators, how to get bills passed, what the bills are that are needed, and we’re doing all of this," Egan says.

And they’re also making it personal, telling victims’ stories through the letter drops.

"Somebody’s going to listen sooner or later," Kramer says. "You were the second place we letter-dropped, On Point radio was. First one was CNN. Next month it’s a news anchor, Tucker Carlson. We’re picking different ones and I just think sooner or later something’s going to get done."

If you or anyone you know is living with addiction and depression, there are resources available for help. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's website or call the helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

This article was originally published on April 17, 2019.