Advertisement

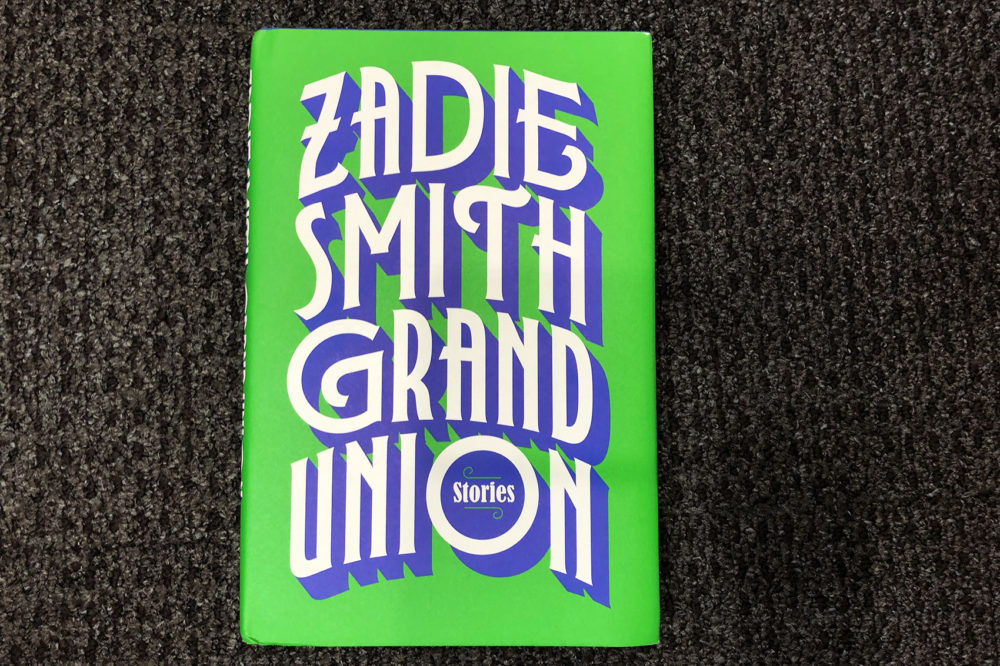

Zadie Smith's First Short Story Collection, 'Grand Union,' Is Here

Zadie Smith is with us to talk about her first short story collection, "Grand Union."

Guest

Zadie Smith, celebrated writer and author of "White Teeth," "On Beauty" and "Swing Time." Her new book is "Grand Union," her first short story collection. Professor of fiction at New York University.

Interview Highlights

On the advantages of the short story format

"I think for me it's about playfulness. ... I guess the thing I always fear is rigidity or getting stuck, and stories were just an opportunity to think differently, think about different kinds of writing, different ways of writing. A novel is a very long stretch in one place. And so it was amazing fun to do this. Fun for the irresponsibility, fun for the freedom, fun because I didn't have to be just one writer. I could be more than one and that's exciting to me.

"And fun because it was there was a lot of improvisation and adaptation. I started to think about it the way I think about music. If I'm making music, or sometimes I sing, and so much of that is improvisation. You have the chords, but then you work around it. And I thought about how rarely you do that in writing. You get so anxious and so stuck. So I experimented with things, like found objects, for example, like trying to write about what fell in front of me on a particular day — something that I think visual artists do a lot of, painters do. I want to see if I could do it in language."

Advertisement

On feeling an obligation to continue experimentation

"I always say to my students I don't think writing is cumulative. I mean, you do get a bit better at it — maybe certain things you have more facility. But, unlike other skills, it's always possible to be terrible at it. That's always a proposition in front of you every time you write a book. It could be the worst thing ever. That's what is exciting to me about it. I don't see a great difference between me and a student of mine. We have the same possibility in front of a book every time, of just being awful. And that's what's kind of thrilling, and exciting about it, and fresh about it.

"I guess you can get stuck in a certain mode and then just reproduce books in that mode over and over, but that was never my idea. I always felt like an apprentice and as someone starting out. And I suppose something about what happened to me when I was very young, with 'White Teeth,' made me feel a responsibility to that kind of luck. I felt very lucky, and kind of outrageously lucky. So I suppose, in my mind, to justify it, I decided to work hard, retrospectively."

"I guess when I'm writing, I lose track of time a little bit. You live in the time of the books you're writing, and then you wake up every few years and realize you got older again."

Zadie Smith

On still feeling like "an apprentice" in the craft of writing

"I do. I think that I have some kind of arrested development. I know I'm 43, but I don't particularly feel that way. I know that I wrote a book 20 years ago, but that seems to me like yesterday. I don't know. I guess when I'm writing, I lose track of time a little bit. You live in the time of the books you're writing, and then you wake up every few years and realize you got older again. To me, the time of the books, I guess, is real time. And it's slow progress. You know you kind of get a little bit better, make a few less mistakes, but learn new bad habits, etc."

On her story "Kelso Deconstructed" in the collection. It's based on the true murder of Kelso Cochrane in 1959. He was just 32 when he was murdered by a group of white youths, none of whom ever faced prosecution.

In the process of writing this story, did it help you understand this moment in British history in a different way?

"It made me understand that there's a part of British history that the British don't recognize and don't understand. Black British history is British history. And until it's included in our classes and no knowledge of our own country. It'll be hard for Britain to change and become an adult country, which it has yet to do my opinion.

"It's a long process for me, of kind of being out of English schools and understanding what was not taught. And, fundamentally, what was not taught was our true colonial history and the true history of British slavery, which is the equal of American slavery. Just because it was offshore doesn't mean it wasn't significant. All these stories — and there so many of them — it's not to punish the British, but if you don't know your own history, you are condemned to repeat it, and you are also condemned to be innocent. I think the British idea, which I certainly had growing up, that we were — 'we' — fundamentally on the side of the angels, it's not a helpful thing to believe as a nation, because it means you go forward in innocence always.

"If you think of yourself as a hero, and a lot of the language we're hearing in the papers — I was amazed, when I got back to England recently — about Brexit is explicitly Second World War, heroic language. Even the smallest article I read in The Evening Standard — 'House prices are falling. It's tin hat time.' — an economic crisis brought on by ourselves, for ourselves is described as a kind of wartime attack.

"You get stuck in these metaphors, and historical truth is a way of escaping metaphorical truth. And I think it would be incredibly healing for everyone in England, black and white, to understand what Britain was in the 19th century. This grandeur that we're always trying to return to was not so grand. And it's important to know that. There's many things to love about Britain. It's an extraordinary place. But it's not an innocent place."

"You get stuck in these metaphors, and historical truth is a way of escaping metaphorical truth. And I think it would be incredibly healing for everyone in England, black and white, to understand what Britain was in the 19th century."

Zadie Smith

On how a writer can possibly avoid biases — and the root cause of those biases and other rhetoric

"My answer has been to get out of the algorithm, personally. And I totally understand it's a luxury of my life: I don't have the kind of job where I need the phone in my hand. But I also think that there are more people, perhaps, than admit it who could get out of the algorithm, who could use the algorithm less.

"I use email to contact people and to be contacted, but I don't enter the hive that often. Just because I can't think in there, I can't think in an algorithm. I don't feel free, and I'm very addicted to freedom, so I try to work outside of it as much as possible. I'm not a Luddite. I know what's going on online, I can see it when I want to see it, but I don't exist within it. I just can't do that.

"Anyone who can think in there, I admire you extraordinarily. But, I can't. And I've been thinking about it a lot. I read a lot of stuff about the digital world. It seems to me that the things that I love about internet are asymmetry — the asymmetry between user and crowd. All of the things that are extraordinary, like LGBTQ visibility and the sudden voice of black women online, that's all to do with the asymmetry. So one person can speak to many, just as you're doing on the radio now.

"But there is a second asymmetry between the users and the data harvesters, and that asymmetry is so toxic and so deadly to me that I can't participate in the first one. But I absolutely dream of a generation who find a way to separate these two internets from each other — the one in which we are talking to each other and have a relation with each other, and the one where we're being manipulated day and night. As long as the two are connected, I can't be in there."

From The Reading List

The New Yorker: "Two Men Arrive in a Village" — "Sometimes on horseback, sometimes by foot, in a car or astride motorbikes, occasionally in a tank—having strayed far from the main phalanx—and every now and then from above, in helicopters. But if we look at the largest possible picture, the longest view, we must admit that it is by foot that they have mostly come, and so in this sense, at least, our example is representative; in fact, it has the perfection of parable. Two men arrive in a village by foot, and always a village, never a town. If two men arrive in a town they will obviously arrive with more men, and far more in the way of supplies—that’s simple common sense. But when two men arrive in a village their only tools may be their own dark or light hands, depending, though most often they will have in these hands a blade of some kind, a spear, a long sword, a dagger, a flick-knife, a machete, or just a couple of rusty old razors. Sometimes a gun. It has depended, and continues to depend. What we can say with surety is that when these two men arrived in the village we spotted them at once, at the horizon point where the long road that leads to the next village meets the setting sun. And we understood what they meant by coming at this time. Sunset has, historically, been a good time for the two men, wherever they have arrived, for at sunset we are all still together: the women are only just back from the desert, or the farms, or the city offices, or the icy mountains, the children are playing in dust near the chickens or in the communal garden outside the towering apartment block, the boys are lying in the shade of cashew trees, seeking relief from the terrible heat—if they are not in a far colder country, tagging the underside of a railway bridge—and, most important, perhaps, the teen-age girls are out in front of their huts or houses, wearing their jeans or their saris or their veils or their Lycra miniskirts, cleaning or preparing food or grinding meat or texting on their phones. Depending. And the able-bodied men are not yet back from wherever they have been.

"Night, too, has its advantages, and no one can deny that the two men have arrived in the middle of the night on horseback, or barefoot, or clinging to each other on a Suzuki scooter, or riding atop a commandeered government jeep, therefore taking advantage of the element of surprise. But darkness also has its disadvantages, and because the two men always arrive in villages and never in towns, if they come by night they are almost always met with absolute darkness, no matter where in the world or their long history you may come across them. And in such darkness you cannot be exactly sure whose ankle it is you have hold of: a crone, a wife, or a girl in the first flush of youth."

The New Yorker: "The Lazy River" — "We’re submerged, all of us. You, me, the children, our friends, their children, everybody else. Sometimes we get out: for lunch, to read or to tan, never for very long. Then we all climb back into the metaphor. The Lazy River is a circle, it is wet, it has an artificial current. Even if you don’t move you will get somewhere and then return to wherever you started, and if we may speak of the depth of a metaphor, well, then, it is about three feet deep, excepting a brief stretch at which point it rises to six feet four. Here children scream—clinging to the walls or the nearest adult—until it is three feet deep once more. Round and round we go. All life is in here, flowing. Flowing!

"Responses vary. Most of us float in the direction of the current, swimming a little, or walking, or treading water. Many employ some form of flotation device—rubber rings, tubes, rafts—placing these items strategically under their arms or necks or backsides, creating buoyancy, and thus rendering what is already almost effortless easier still. Life is struggle! But we are on vacation, from life and from struggle both. We are 'going with the flow.' And having entered the Lazy River we must have a flotation device, even though we know, rationally, that the artificial current is buoyancy enough. Still, we want one. Branded floats, too-large floats, comically shaped floats. They are a novelty, a luxury: they fill the time. We will complete many revolutions before their charm wears off—and for a few lucky souls it never will. For the rest of us, the moment arrives when we come to see that the lifeguard was right: these devices are too large; they are awkward to manage, tiresome. The plain fact is that we will all be carried along by the Lazy River, at the same rate, under the same relentless Spanish sun, forever, until we are not."

New York Times: "Zadie Smith Experiments With Short Fiction" — "To consider yourself well versed in contemporary literature without reading short stories is to visit the Eiffel Tower and say you’ve seen Europe. Not only would monumental writers be missing from your literary tour, but entire angles and moves and structures of which the novel, in its bulk, is incapable. The quirky neighborhood, the narrow cobblestone alley, the stray cats and small museums and the store that sells only butter.

"Since the publication of 'White Teeth' in 2000, readers have known Zadie Smith as a novelist of tremendous scope, a maximalist with a global eye and mind. Those who’ve been paying attention have also caught her stories along the way in our better magazines and journals — stories that until recently have, for the most part, followed a linear narrative, taking advantage of the shorter form but not its more eccentric powers.

"Some of these more traditional stories have landed in Smith’s first collection, 'Grand Union,' and while still brilliant on the level of the sentence, the paragraph, the often hilarious skewering of humanity, they’re the least successful ones here, sour notes in a collection in which the best pieces achieve something less narrative and closer to brilliance."

This program aired on October 10, 2019.