Advertisement

Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen's quest to make the internet safer

Facebook hired Frances Haugen to help it filter out violent rhetoric and abusive behavior.

But she says the company ignored her team’s recommendations.

So, in 2021, she leaked thousands of pages of internal documents to the media.

"It erodes our faith in each other, it erodes our ability to want to care for each other, the version of Facebook that exists today is tearing our societies apart."

She testified before Congress:

"I saw Facebook repeatedly encounter conflicts between its own profits and our safety. Facebook consistently resolve these conflicts in favor of its own profits."

Now, she has a new memoir, "The Power of One."

"We deserve to know what the risks are of the projects we use. We deserve to be able to ask questions and get real answers. And if we don't push for that, we're not going to be able to live in a world with safe technology."

Today, On Point: Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen.

Guests

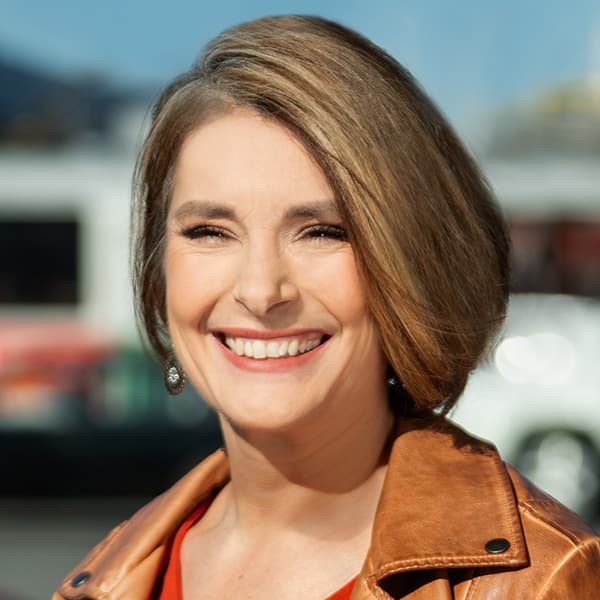

Frances Haugen, data engineer who worked for Facebook from 2019 to 2021. Author of "The Power of One: How I Found the Strength to Tell the Truth and Why I Blew the Whistle on Facebook."

Excerpt

Excerpt of "The Power of One: How I Found the Strength to Tell the Truth and Why I Blew the Whistle on Facebook." All rights reserved. Not to be republished without permission.

Transcript

Part I

TIZIANA DEARING: Frances Haugen. What was your first job at Facebook? What did they hire you to do?

FRANCES HAUGEN: Many people probably have heard of the Facebook third party fact-checking program. It's where they hire journalists to go and fact check extremely popular stories on Facebook.

Most people aren't aware that program only covers a very limited corner of Facebook. So it covers parts of America, like the most popular content in the United States, the most popular content in Western Europe. But for majority of countries in the world, there are no third-party fact checkers.

And even in major countries like India, you might only have a couple hundred stories fact-checked every month. My team, I was recruited to Facebook to work on the problem of what do you do about misinformation when you can't rely on third-party fact-checking? How do you change the system or do other things beyond just taking down individual pieces of content?

Advertisement

DEARING: And when did you realize that you weren't gonna be able to do that job? You couldn't succeed at the job for which you were hired?

HAUGEN: So I think the question you're trying to ask is like, why did I decide to blow the whistle? The moment I realized --

DEARING: N, no. I want to go back. Because in the memoir there is a moment earlier on where you're like, "Wait a minute."

HAUGEN: Oh yeah.

DEARING: So let's start there.

HAUGEN: Sure. So I realized probably within a couple of months that it was not going to be possible for me to accomplish that objective. Because at Facebook, nothing was considered false unless it was third-party fact-checked.

And so we lacked, we were not well aligned with how Facebook operated or defined success.

DEARING: All right and I appreciate you letting me restear you back.

HAUGEN: Sure, no worries.

DEARING: We are talking with Frances Haugen today because she has a new memoir out, "The Power of One: How I Found the Strength to Tell the Truth and Why I Blew the Whistle on Facebook."

That's probably how you know her listening right now as the Facebook whistleblower. In 2021, she disclosed 22,000 pages of internal Facebook documents revealing what she says are both failures and culpability at the social media giant around some profound social harms. Frances, now I'm going To say welcome. Thank you for joining us.

HAUGEN: Thank you for inviting me.

DEARING: So I do want to get into that big question that you posed, but I want to go back a little bit because there this story of from engineer to whistleblower, and I want to go back to engineer. You spent your whole career up to the whistleblower moment in tech.

All the way back to Olin College of Engineering. What drew you into the tech industry Frances?

HAUGEN: I have always loved to build things, so I went to a Montessori preschool, and I remember, I loved that they would even let small children, like three- and four-year-olds use real saws and real hammers.

And I built some very ugly boxes, as you can imagine. And my father was always very willing to do projects with me, so he really liked tinkering and so he would let me tag along. And that really set the stage for my getting into college. And so I ended up only getting, I was interested in a variety of subjects, but I only got into technical college.

DEARING: So you go to technical college and then you go into a number of prestigious companies before Facebook, with brands like Google, Pinterest, Yelp. And I want us all to understand, because I want us to know the expertise you bring into Facebook. As you begin to evaluate what's going on there, what kind of things were you building with this passion for building things?

HAUGEN: So I was incredibly lucky in that I stumbled into Google, and I really can't say I navigated to Google. Because I got one job out of college, because back then Olin College of Engineering wasn't accredited. And I had I detailed it in the book the things you don't think about when you're an 18-year-old applying to a new college is when you graduate, you'll not have an accredited degree immediately.

So I got one job 'cause Google was willing to be flexible. And I ended up in California right as the function at Facebook of product management, that's the process of, it's more of the user experience function around search quality. Which is the process of like, 'How do you pick out which websites to give someone, what should they look like, when should you show them to them?'

That function was just starting to be built out in 2006, 2007, and I fell in love with the fact that people are more honest with Google, with search engines, than often anyone in their day-to-day lives. You'll ask questions where you're very vulnerable, you'll ask questions about your curiosities.

And it was amazing getting just to have this window into like kind of the subconscious of humanity. And I loved being able to help people, right? Like I loved that in that moment when someone reached out and wanted help. We could help them. And that's how I really fell in love with building things.

DEARING: So how could you help them? What's something you did with the search engine when you were at Google?

HAUGEN: Sure.

DEARING: That made it, I don't know. Better for somebody in a vulnerable moment. In an intimate moment to find what they were looking for.

HAUGEN: So I think the thing I'm most proud of that I did on search was we figured out a different way.

So when you're trying to build a search page, you have to reach into something called an index, which is think of it as your library. You have to walk into your library and you only get to put a limited number of books on the shelves. And prior to this change, we were putting whole books on the shelves instead of individual pages.

And let's be honest, every page of every book is not equally valuable. I had figured out a clever trick for looking at data and figuring out how do you pick out individual pages? And part of why that was like such a magical change for me was it let us bring in a greater diversity of content.

A greater diversity of languages. And so we were able to serve users who might not get to use the richness of the English Internet to get answers in a very different way.

DEARING: So now when I think about your description of the job you were hired at Facebook to do, it starts to flesh out a little bit more, and I understand I'm skipping a lot and some of it we'll touch on further.

HAUGEN: No worries.

DEARING: I wanna fast forward now, Frances Haugen. In 2018, you get a call from Facebook with that just ringing in our ears, why do you think Facebook wanted you?

HAUGEN: So I don't have any grand interpretations of why Facebook reached out. I was one of a handful of people who worked on algorithmic products especially in product management.

It's not super common, or at least it wasn't back then. And they would email you, four times a year, just to see, "Are you now maybe interested in working at Facebook?" And but the thing I did differently that time when they reached out, was I fully admit, flippantly, said to them, the only thing I would do at Facebook is work on misinformation.

Cause I didn't care what they said. And I was totally pushed back when they were like, "Oh we actually have a job around that. Like you could work on civic misinformation." And that's how I began, becoming open at least to the idea that maybe I would work at Facebook.

DEARING: And you had a close friend, Jonah, who you felt had been radicalized some via misinformation in the 2016 election cycle.

HAUGEN: He describes the experience that he had online as he was radicalized online. I can't blame Facebook specifically, like I think it was probably more things like 4Chan and Reddit.

But over the course of a very few months between when Bernie Sanders lost the nomination and the election in the fall, he turned online to commiserate with people who felt that Bernie had been wronged. And in the process of finding places where people were aggrieved, he ended up also getting pulled down the rabbit hole. And beginning to believe some pretty non-consensus reality beliefs like George Soros runs the world economy, that kind of thing.

DEARING: And so you wanted to work on that.

HAUGEN: So the pain of watching Jonah pull back from our shared reality was incredibly painful for me. Because I had gotten quite ill in my late twenties to the point where I had to relearn to walk. So I spent seven weeks in the hospital. I almost died.

There was a period of time where I got a head injury and like I had to, I couldn't speak, imagine how verbal I am. I couldn't even form a sentence. And during the period of my recovery, and the thing they don't tell you about recovering from such a health scare is that it takes a long time.

It's lonely, it's boring. And Jonah was, I want to think we were both lost. He was in his early twenties, he had just moved to the Bay Area. I initially hired him as like an assistant so I could clean out a storage unit. I was too weak to carry the boxes back and forth to the storage unit or take trash out.

But we became really good friends and when I watched him slip away it felt like my friend was dying. And when that Facebook recruiter reached out, I think if I hadn't had that experience of this person who I credit my recovery to, I credit the fact that I have the life I have today to, if I hadn't lost him to misinformation, I don't think I would've given that recruiter the time of day.

DEARING: So we go forward and we're going To have to take a break in a minute, but we go forward to June 2019. There you are. Very quickly, somebody who's supposed to mentor you says, "I don't understand why your team exists, and I don't think it should exist." What do you do in that moment when you've come to take on something that's so deeply important to you?

Advertisement

HAUGEN: So for context for most of your listeners in, in any standard job, if you're hired to solve a problem, they still expect you to take a couple months to learn how the company operates.

DEARING: Frances, I'm just going to interrupt you and tell you we have to go to break in about 30 seconds. So just heads up.

HAUGEN: Sure. So the person who was sent to mentor me, he was asking me, "What are your projects?" And because by definition civic misinformation was misinformation beyond what was dealt with by third party fact checking, there was no way for us to measure that we actually were taking down the thing that we were assigned to. And so he said, "You shouldn't work in this space." And that's a pretty interesting set up to what comes next.

Part II

DEARING: So Frances, you're now there.

You've been told it's going to be too hard to measure what you're trying to do in civic misinformation. Your team probably shouldn't exist. You should be doing something else. It's a problem that's deeply important to you. But there are these three dimensions that you discover of what's wrong and I want to see if I can really simplify these.

Basically, over time, despite the fact that you can't measure how you're trying to work against them, you discover inside the organization there are these problems. People can be harmed by working, using Facebook. People can be driven towards harmful thinking. And it can be easy for bad people to do harmful things.

Is it fair that over time while you're trying to combat misinformation, you discover this about the company you're working in?

HAUGEN: So I worked within a relatively narrow scope, so my focus was less on, so when you talk about bad people doing harmful things, unquestionably there are many problems on Facebook, like human trafficking acts by cartels to intimidate local populations or recruit members.

There's a lot of stuff that is at that level. The scope of what I worked on was initially what causes, what can be done when there is an explosion in Sri Lanka and misinformation is threatening Muslims with ethnic violence> Like what, how can you turn down the heat when the fire starts raging? Or for example what I did next, what can you do if the police are being targeted with misinformation specifically in the United States? So I would say I didn't get to cover the full continuum of what you described.

DEARING: No. And I didn't mean to imply that you worked on all of that, but I did want to understand.

Am I summarizing correctly that over time as you discovered problems at Facebook, it was across all three of those areas? Is that a fair summary?

HAUGEN: Yeah, that's fair.

DEARING: Okay, so let's pull those things out. You just gave two examples there. Two of the things that you worked at. One, what can be done when there's an explosion and now people face harm.

One of the things that was really striking was your discussion, your discovery about Facebook, excuse me, and its role in Genocide in Myanmar, and I'm going to play some troubling sound here. I do want to note for listeners this is hard to listen to. The NGO Human Rights Watch released a video in 2017 describing the systematic rape and killings of the Rohingya minority in Myanmar.

We have been investigating the particularly brutal massacre in the village of Tula Toli. We're literally talking about several hundreds of men, women, and children who were killed.

TRANSLATION: I don't have any of my brothers and sisters left, says one woman. Another woman says they snatched the toddlers from their mother's laps and threw them into the river. A few of the children were set on fire and a few were chopped to pieces.

DEARING: This is hard stuff, Frances Haugen. You were made aware early on of a sense that Facebook's offering of free basic in the country, its lack of providing sufficient safety oversight there, may have contributed to what you say in the book is facilitating the deaths of 25,000 people, and the displacement of 700,000 others. And so it was work like that you then were working towards mitigating going forward? Yes?

HAUGEN: So it's not my opinion that Facebook played an active role in that genocide.

The UN released a 250-page report in, I believe 2018 or 2019. That very clearly said Facebook is at fault because of negligence. They didn't have anyone, they had one person in the company that spoke Burmese. And when that person said, "Hey, you have a problem, your platform's being weaponized by people trained in Russia."

The New York Times did a great deal of reporting on that, is being weaponized and used to kill people. There was no mechanism for that information to move up the reporting chain at Facebook. So the experience I had regarding Myanmar was one of the things Facebook agreed to as a result of that report, was they would provide a channel for people like human rights watch to flag when things were going off the rails.

They made a trusted inbox. So people could safely message a specialist, get 24-hour turnaround. They said, we're going To do it different this time. And one of the first projects I worked on at Facebook was, "Okay let's upgrade that service." And what we discovered was Facebook had promised to build the inbox, but they had never promised to maintain it.

So that mechanism for contacting Facebook was so out of date that we were going to be required to invest six months of work just to bring it into compliance with how the rest of Facebook functioned. And that was like my first shocking wake up call to like how Facebook allocated resources.

DEARING: Can I ask you and I almost said this out loud to you while I was reading the book, why not quit right then, Frances?

Why is that not the moment where you say, I can't be here?

HAUGEN: So one of the things I write about in the book is this idea that all Facebook employees who work on safety face quite an arduous dilemma, which is, once you learn a truth like that, it's totally true. It's a reasonable thing to say, "This is too much.

I'm going to quit." Maybe you write a memo, hope that someone else deal deals with it at some point. Another option is that you stay, and you keep trying even though you know you don't have enough resources. Because at least you have one person who's trying to make it a little bit better, even if it might not be enough.

But one of the things I saw over and over again was my coworkers really dearly burning out as a result of that kind of thinking. And I did not have the arrogance to believe that I could be a one-woman solution to problems of that magnitude. Like the conclusion I came to was a third way, which was the public needed to come help save Facebook from itself.

DEARING: So as you are there, you get there in 2019, the decision and the documents were forward in 2021. During that time, you've just laid out one of the projects that you work on that underscores a problem. Let's talk about a couple of the other key problems that you found. One of the things that was striking to me was this idea that Facebook was constantly making choices, that you felt the company internally was framing as, "We don't have the resources."

But that you felt the company was actually saying, "We're choosing not to allocate the resources." And that was not only having a significantly harmful effect in the world, but grinding down people on the inside as well.

HAUGEN: I'd love people to take a step back and think about Facebook's profit margins. Most businesses have very moderate profit margins. We're talking 5%, 7%, maybe 10%, 12% if they're really lucky. Facebook's profit margins are north of 20%, north of 25% most of the time. Facebook could have spent small amounts more money. We're talking millions of dollars more per year, when you have tens of billions of dollars in revenue per year, to make sure you did have enough people working on things like genocide.

And so Facebook I heard over and over again from people, it's just so hard to hire. There's no way we can hire. And it's like when you have tens of billions of dollars in extra money laying over at the end of the quarter, if you can't hire people to work on genocide, it means you're choosing not to.

Not that you can't.

DEARING: So I want to know, we reached out to what is now Meta. Of course, we're using Facebook because that's what it was at the time you were there. And to keep it simple, we did reach out to them. We did not hear back from them in time for this broadcast. I'll pull up a little bit of comment from Mark Zuckerberg in a blog that he posted after your Senate testimony on October 5, 2021. And it's a longer blog. I'm going to bring up a little bit of it here. It feels like the right point to bring in his voice.

MARK ZUCKERBERG: At the most basic level, I think most of us just don't recognize the false picture of the company that is being painted.

Many of the claims don't make any sense. If we wanted to ignore research, why would we create an industry leading research program to understand these important issues in the first place? If we didn't care about fighting harmful content, then why would we employ so many people dedicated to this than any other company in our space? Even ones larger than us.

DEARING: That's a pushback to the idea that there was insufficient investment, Frances.

HAUGEN: So they have the largest social network in the world by a huge margin. So even at Twitter's height, Facebook had probably five, six times as many users. So Facebook has 3.1 million users around the world, and Twitter maybe had 400,000, 500,000.

Also, what's quite ironic about that whole blog post now is Facebook has fired a huge fraction of all those researchers today. In the quote "year of efficiency," they have radically reduced the size of their trust and safety team. And so it is interesting that was the way he framed it at the time of the event.

And now that to quote Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk has showed you can rip off the Band-Aid. I.e., fire a lot of people.

DEARING: You're referring to him buying Twitter, which is now X?

HAUGEN: I'm referring to him, like Twitter has 25% as many employees as he bought it like Musk, straight up fired half of the company and there were no consequences.

We live in a world where there is no transparency for the social costs of these platforms, and so you can borrow or steal from the social side of the balance sheet and make your economic side of the balance sheet look more plump.

DEARING: So I want to pick up on another thread here, and we're speaking with Frances Haugen the author of "The Power of One." And we're constructing here what you were discovering there that leads you to then reveal 22,000 pages of internal documents. You've laid out the lack of attention and resources paid to safety for violent areas, et cetera.

We've talked about why you didn't quit during that process. Earlier I asked you the skill set you brought in and you made reference to algorithms. One of the things that you unfold in the book is a change that Facebook made to the way, and I'm going to use a lay term, right?

The way Facebook pushes content. Around 2018 that you really felt was a pretty profound change. Do you think there's a simple way that you could explain to us what that was?

HAUGEN: Mark Zuckerberg actually quote, wrote a white paper, probably one of his employees did, but his name's on it. From 2018, that says when we prioritize content, every time you open your phone, Facebook looks at 100,000 or more pieces of content and says, "What should we show you now? What should we show you first? What should we show you second?" When you make that process decision, when you decide, "Okay, I'm going to show you this first." Based on the likelihood that you're going to click on it, that you're going to reshare it, that you're going to put a comment on it, you end up biasing, you end up giving the most distribution to the most extreme content.

And he lays it out himself in that white paper. In 2018, they adopted that method of prioritizing content. Before that, they said content is good if you hang out on Facebook longer. It was based on your total time spent on site.

DEARING: Does the rest of the tech industry get a complete pass on that? And here's what I mean. The algorithmic development that's happening everywhere else in Google. Other companies. In the decade before that, does any of that make it possible for Facebook to do what it does at that time, that leads to what you believe and have asserted?

And we'll come to some research a little bit later in the show to have been such a harmful change.

HAUGEN: Sorry, can you repeat the core part of the question again? It was a long question.

DEARING: Work in the tech industry, up to that point.

HAUGEN: Oh, anyone else? Anyone else?

DEARING: Yes. Yeah, anyone else culpable.

HAUGEN: I think one way to think about it is most other tech companies have more of a recognition that they have power. Facebook's a big part of what I lay out in the book, and for those who are listening, who feel like this is a really intense conversation, trust me, the book is full of fun, playful stories, and it is a policy book for people who don't like policy books.

The other companies like TikTok, TikTok is a product that is driven by algorithms even more than Facebook is. TikTok was also designed with the idea that choices about content, choices about allowing children on the platform are not, are serious choices. That TikTok holds power, and that the danger with Facebook was that they developed a management system that devalued human judgment.

That said, as long as the metrics go up, it's a good thing. Ignoring the fact that all metrics-based systems can only capture a sliver of the issues that matter in any given system.

DEARING: There is a moment where you talk about preparing for the 2020 election and the organization identifies 60, I think you called it, deep blood, red colored hotspot potential problems, and decides it can tackle maybe 10 of them.

And that again is an allocation choice that you feel the company made. That's the kind of thing you want us to understand about these choices. Yes?

HAUGEN: For context, because the deep red blood thing might not make a ton of sense. Imagine you went through and made a chart describing where the vulnerabilities might lie on Facebook.

It could lie on Facebook, it could be on Instagram, it could involve groups, and it could involve hashtags. It could involve messaging. Imagine you went and made a chart and there were 60 boxes on it, and 50 of those boxes were red. Only a few were yellow, none were green. But you only have enough resources to pick 10 boxes out of those 50 that you actually quote, have enough staff to tackle.

So that's a great example of where Facebook could have taken some people off of ads targeting for a couple months. They could have not done another animated emoji for a couple months. Those are choices. They had the ability to, they chose not to.

DEARING: So in a minute, we're going to have to go to another break, and when we come back, I want to get into the choices that you think we need to make as a country and that social media need to make going forward.

You then, at the beginning of 2021, make a choice to blow the whistle, as we go out, in just two sentences. Was it the hardest decision you've ever made?

HAUGEN: Oh, great choice or great question. I would say almost certainly the idea of should I bring information to the public was one of the hardest choices I had ever made.

Part III

DEARING: We're talking about the real challenges that human beings are facing from social media now and maybe looking forward a little to artificial intelligence. But Frances, I want to talk about sunshine for a minute. Both literally and metaphorically. Because, so now we move forward. 2021. You have made the decision and you have executed on it to get these 22,000 pages. You work with the Wall Street Journal, you give an interview on 60 minutes, you testify before the Senate, you have moved to Puerto Rico.

Which is better for your physical health. You don't work at Facebook anymore. The sun is shining on you, and you have shed sunlight on something that you think is so important. Talk about for just a minute, this moment in your life.

HAUGEN: It was so interesting. Like before, so I had not really ever considered being a public person? So one of the things I talk about a great deal in the book is the idea that I grew up in the Midwest. Being the center of attention is not a thing that I am super comfortable with. I tried really hard to have a wedding the second time I got married and I eloped again.

Like it's one of those things. And though I did get to elope on a beach in Puerto Rico, so it was still lovely. But at that point, so I've come out, I've come home, right? The thing that I was really struck by was, you have these visions in your mind that you blow the whistle on a big company and there's going to be paparazzi. Or maybe someone on the internet will get strange ideas about you and come yell at you, or, who knows, private investigators.

And I was so grateful that none of that happened. And I sometimes say that Puerto Rico protected me. Because, if you want to come yell at me, you have to get on a plane and get a hotel for at least one night. And just that activation energy keeps some people on the internet away. Or I feel like the world really received my critique in a positive and welcoming way, and I'm incredibly grateful for that.

DEARING: So I want to come forward now, and it was surprising to read that the retribution you were worried might happen, didn't come. And that struck me next to the retribution that it seemed might happen for Facebook, for those who fully leaned into what was coming out in these stories. And I wonder if it has come. I'm going to play a little sound from a congressional hearing.

In October of 2021, Senator Richard Blumenthal, chair of the subcommittee on consumer protection, he is grilling Meta's Global Head of Safety, Antigone Davis.

SEN. BLUMENTHAL: Facebook has taken big tobacco's playbook. It has hidden its own research on addiction and the toxic effects of its products. It has attempted to deceive the public and us in Congress about what it knows, and it has weaponized childhood vulnerabilities against children themselves.

DEARING: I'm noting that big tobacco playbook because just recently you gave an interview where you said you were still waiting for social media to have its cigarette moment, and I'm assuming you mean when the world turned against big tobacco.

HAUGEN: Actually, we've begun in many ways the big tobacco moment because just maybe, I guess two months ago now, the Surgeon General came out and did a national health advisory on how teenage mental health was in danger because of social media.

Everything from sleep deprivation, 30% of kids say they're on screens till midnight or later, which means 10% are probably on till 2 a.m. Escalating rates of depression, things like that. Average kid spends 3.5 hours a day on social media. Just for context for your listeners, there've only been maybe 10 or 15 of these advisories since the '60s.

And historically, within two to three years after one of these advisories comes through, we usually see some major law or something like the attorney generals, that's what happened with big Tobacco, bringing a lawsuit that acts like a national law. And so I think our big tobacco moment is just beginning.

It's not that it hasn't happened yet.

DEARING: Do you have faith that our Congress is capable of passing the laws in this moment that would provide sufficient regulation? I'm noting two things. One is a move yesterday, for example, by an unlikely pair. With Orrin Hatch not Orrin Hatch, excuse me.

Lindsey Graham and Senator Elizabeth Warren saying they want a new federal bureau, basically a new federal department that's going to provide oversight to big tech companies. A move like that, A, good idea? B, do you think something like that can happen now?

HAUGEN: So just for, again, to remind your listeners, for Big Tobacco, it never happened at the federal level.

It happened from the attorney generals and we're starting to see very large lawsuits. Like the Seattle Public Schools bringing a lawsuit on the costs of mental health, dealing with the mental health impacts of social media and teenagers. In the case of a national department, I haven't had a chance yet to analyze what exactly their request is asking.

I'm a huge proponent of transparency, and in the book, I walk through why we need even minimal transparency if we want to be able to really reign in these companies. But I get a little nervous sometimes when we start talking about specific actions. Because we are living in an in-between time, I would say, where every social issue has a finite number of children who are willing to accept being harmed.

When it comes to cars, we put eight-year-olds in car seats. Think about that for a second. Think about how annoying it is to have a eight-year-old fight with you about the car seat every day. It saves like 60 kids a year. Not a big mover, but we don't accept those deaths. A lot more than 60 kids a year are dying from social media.

And when we look at places like Utah or Montana, places that are conservative, they're starting to pass really extreme laws. Things like in Utah, getting rid of youth privacy online. Montana, they banned TikTok. I hope that if we have an oversight organization, it's something like what the European Union passed last year, which is they came out and said, 'We have the right to have tech companies disclose the risks of their products. We have the right to ask questions and get real answers, and we have the right to be able to research independently what these platforms are doing so we don't have to just accept what they tell us as truth.'

DEARING: I want to bring up something that's come forward in the last 24 hours. Because one of the things we talked about earlier in our conversation and that you've talked about in addition to the transparency, is this sort of, again, my layperson's term, algorithmic focus and approach that Facebook has used. Facebook engaged in some research, made some data available to 17 researchers, 12 universities.

And Science released a package yesterday, the first of some articles that are coming out. Facebook also released a statement. There's some, okay, let me do a better job at this.

HAUGEN: (LAUGHS)

DEARING: The first of it comes out yesterday. Facebook frames it as the research is going to show that our algorithms didn't cause problem.

Science says quote, "significant ideological segregation" end quote. Comes from the platform, but also according to an NBC news article, quote, "It was not clear whether this segregation was caused more by algorithms or user choice." End quote. If it's not clear, then is Facebook the problem? Or as some of the researchers involved say, over time, will we see it's more complicated than that, and the algorithms will be a piece of this puzzle?

HAUGEN: So one of the things that's fascinating about this research project is that they had an independent, what's known as reporter, which is basically a journalist who rides along and goes to the meetings and figures out is this actually independent research? Is this a thing where like Facebook has genuinely not interfered?

And one of the things that came out of that analysis was, these are very limited experiments. You had a situation where the journalists, not journalists, the academics made some reasonable guesses on experiments to run. But remember they're playing uphill ball with a bunch of Facebook employees who have all the data, they have all the prior research and the experiment that Facebook points at as saying, 'Oh, this proves that our algorithms didn't do anything.'

You can't design a whole product with the assumption that an algorithm will be there. Then remove the algorithm and say, 'Oh, this is the impact of the algorithm.' So I'll make that a little clearer. When you and I joined Facebook, or when Facebook got its first feed, you did not belong to any million person groups.

A group, a Facebook group with a million members or 100,000 members. Because if you had that group, your feed would've been flooded with content from just one group. A million people might make a thousand posts a day. Facebook's experiment said, 'We're going to turn off the algorithm, but leave you in those million person groups.'

Is it surprising that they didn't see any change in results or behavior just when they turned the algorithm off? And Science magazine warned Facebook a week in advance and said, "If you come out and say, this proves we're fine. If you say, this exonerates us, we will openly challenge you." Because the research does not say, Facebook didn't do anything.

It says the specific experiment that was run showed little effect.

DEARING: So that is then of course, exactly what's been unfolding this week. So as we move forward, I want to move us forward a little bit. Because one of the things that has been, I think, heavily on my mind in reading the book, were your references to AI.

So, for example at the top of every chapter you have a quote from someone else, and one of those quotes is dumb AI is basically more dangerous than strong AI. In a interview with Wired in June of this year, you referred to us as backing away from what you call quote, "the AI hype ledge" end quote. I was really intrigued by that.

Because there is so much conversation right now about the fact that we are under appreciating the level of danger of very strong AI. So one, with where AI is now, and it's not where it was when you wrote the book, is it still better to have strong AI than dumb AI?

HAUGEN: What I mean by dumb AI is you know, the people who are telling you about how the world's going to end.

Are talking about problems that are almost certainly at least 20, if not 30 or many further years away. But in that time, just the current version of AI we have, not even the version of AI we had when I wrote the book, is powerful enough to really destroy society. I'll give you, I'll really give you a really concrete example.

I'm at a conference right now in Cambridge, United Kingdom, so not Massachusetts, Cambridge. And there was a Facebook representative here and she talked about how AI was important because it can do content moderation. And I got up and I asked a very simple question. I said, "We have had an academic field called adversarial AI."

So adversarial AI is what it sounds like. It's about tricking AI. It's like, how can I fool AI? And it's really interesting. You can create images that look like penguins, not penguins, like pandas. And you can add a little bit of noise to that image that was designed to trick the AI and it'll make the AI think it's a monkey.

We're about to enter a very different world where part of the Digital Services Act is, it says, "You have the right to know your content was taken down. You have the right to know if Facebook demotes you." When we have that information and we're writing an AI that's trying to trick Facebook's content moderation systems, we now can tune every little piece of misinformation to be just slightly different enough that it gets through the filters.

So we're about to live in an era where content moderation will not work anymore. We don't need suicidal, homicidal AI to ruin the world. We need chaos monkeys that are sowing information operation campaigns, that are making us distrust ourselves and our neighbors.

DEARING: So I want to understand that better.

I that is why I was surprised to see you refer to something like an AI hype ledge, which feels like you're being dismissive. That doesn't sound like something to dismiss. Am I misunderstanding you there?

HAUGEN: Sure. So when a lot of the people who are painting doomsday scenarios, their doomsday scenarios are not that, that's a problem that's now. That's a this week, this month problem. That's a, we need to fix social media immediately. And there's ways to do it. We can design around safety by behavior, not by content, but the people who are going on TV and saying this is an existential risk are talking about AI's designing viruses and AI's launching nuclear weapons.

That is the hype machine. We need to be fixing social media right now, because we don't need infinitely smart AI to do dangerous things. We need even just AI of today, and that AI has escaped. Facebook made its model open source. China released an even bigger model. The UAE launched an even bigger model.

The AI is out there. That means we have to fix social media today.

DEARING: So with that ringing in our ears and 60 seconds left to go, I do, at least for myself, need to ask you. What's one thing that's giving you hope?

HAUGEN: Oh, we have lots and lots of solutions. Like part of why I brought so much forward in the Facebook files was Facebook knows how to design these systems to be safer.

Social media, that's about your friends and family, that's human scale, can be safe by design. And we need to insist today on transparency. So there's incentives to build social media that makes us happy, that's good for us and our communities.

DEARING: And you believe we can do that with the will we collectively share now?

HAUGEN: We need to stand up and demand transparency because we can do it today. We just have to have the right incentives in place.

DEARING: And for you, what's next, Frances Haugen?

HAUGEN: I'm founding a nonprofit called Beyond the Screen. And we're focusing on ways to empower investors, litigators concerned citizens, to be able to stand up and demand more from social media.

This program aired on July 28, 2023.