Advertisement

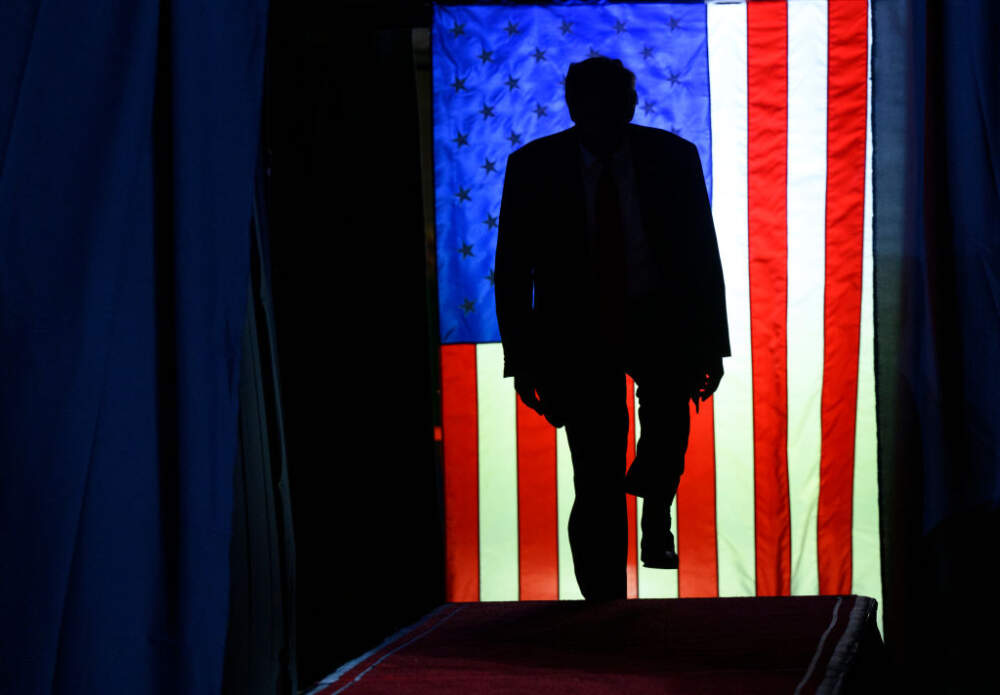

Inside Georgia's indictment of Donald Trump

Former President Donald Trump faces racketeering charges in Georgia for his efforts to overturn the 2020 election.

From violations against Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act to the “fake electors” scheme, how does this indictment compare to the previous allegations?

“His unlawful aim was to deprive Georgians of their right to have their vote counted. And that’s really what this fundamentally is about," political scientist Anthony Michael Kreis says.

Today, On Point: Inside Georgia’s indictment of Donald Trump.

Guests

Anthony Michael Kreis, assistant professor and political scientist at Georgia State University College of Law with expertise in constitutional law.

Chris Timmons, trial attorney at Knowles Gallant Timmons. He served as a Georgia prosecutor for over 17 years in DeKalb and Cobb Counties.

Transcript

Part I

FANI WILLIS: A Fulton County grand jury returned a true bill of indictment, charging 19 individuals with violations of Georgia law arising from a criminal conspiracy to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election in this state.

DEBORAH BECKER: hat was Fulton County, Georgia District Attorney Fani Willis on Monday announcing the indictment of former President Donald Trump and 18 alleged co-conspirators. It was Trump's fourth indictment this year and the culmination of a two and a half year long investigation. What started the inquiry was a phone call on January 2, 2021, when Donald Trump called Georgia's Secretary of State, Brad Raffensperger and urged him to quote, "Find the votes."

DONALD TRUMP: All I wanna do is this. I just want to find 11,780 votes, which is one more that we have, because we won the state. And flipping the state is a great testament to our country. Because, and there's just a, it's a testament that they can admit to a mistake or whatever you want to call it. If it was a mistake, I don't know.

Advertisement

BECKER: That 11,780 number well, in Georgia, Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election by a narrow margin of 11,779 votes. Trump refused to accept those results and insisted without any evidence that election fraud was to blame. Here's Trump in front of a crowd in Georgia on January 4th, 2021, just two days after that call with Raffensperger.

TRUMP: I want to thank you very much. Hello, Georgia, by the way, there's no way we lost Georgia. There's no way, a rigged, that was a rigged election. But we're still fighting it, and you'll see what's going to happen. We'll talk about it.

BECKER: That same day, democratic congressional leaders asked the FBI to open a criminal probe into Trump over the Georgia phone call.

And in Fulton County, Fani Willis officially began her tenure as district attorney. About a month later, Willis announced that her office was taking a look.

WILLIS: There's no way on January the fourth, we could have done a proper investigation, but I will give anyone that we're looking at the same courtesy, which is that we will look at them thoroughly and their conduct.

We're gonna look at the laws, we're gonna look at the facts, and we're gonna make a decision.

BECKER: Now with those decisions made, today, On Point, we'll look at the fourth indictment of former President Trump. What we need to know about how these alleged charges differ from what we've seen before and what's going to happen going forward.

Joining us first is Anthony Michael Kreis. He's Assistant Professor of Law and Political Scientist at Georgia State University College of Law. Welcome to On Point, professor.

ANTHONY MICHAEL KREIS: Hi Deborah. Thanks for having me.

BECKER: So let's start with what stands out for you in this indictment? What do you think are some of the main things we should know?

MICHAEL KREIS: I think Fani Willis has done some remarkable work in really providing granular level detail about the alleged racketeering enterprise that Donald Trump and his allies created, not just in Georgia, but on a national level, to reach into Georgia and to attempt to overthrow the election from November 2020. Despite the fact that there was no credible evidence of election fraud ever.

And despite the fact that Georgia, unlike some other jurisdictions, not only counted our votes accurately the first time, but we had a second recount, we had a third audit, and then that vote was certified. And even then, Brad Raffensperger took the extra step to ensure that Donald Trump felt good about the election results.

By asking Cobb County to do a signature match on mail-in ballots, which once again determined that there was no evidence of widespread fraud. I think that the indictment really speaks to both the extent of the enterprise and how wide sweeping it was. And also to the facts on the ground, which was, bottom line, there was no election fraud in the state of Georgia.

BECKER: And this indictment uses Georgia's racketeer influenced and corrupt organization or RICO Act. So it's an interesting legal strategy here and we'll talk more specifically about RICO, but there's a narrative here. It's not just that Georgia counted the votes three times and there were still these efforts to try to say that there was election fraud, despite the fact that it had been proven that there wasn't.

There's a whole narrative to tie former President Trump and these 18 others together in a criminal conspiracy. Can you explain?

MICHAEL KREIS: Yeah, so I think the indictment really shows and highlights how from the very beginning, before any ballots were counted in the state of Georgia, Donald Trump wanted to maintain power and he wanted to do so by alleging election fraud, again, well before votes were counted, so without any basis. And the way in which he did this was first and foremost by coordinating with a number of his closest allies. Many of them being lawyers to devise a number of different schemes in order to overturn the election.

And as the indictment shows, every time one scheme failed, Donald Trump and his allies moved on to another one, and then they moved on to another one. And the underlying importance of all the lies that Donald Trump told, and I think there are a lot of people who say Donald Trump is being, essentially, targeted for his political speech, and we are criminalizing political speech.

That's not true. But I think what the lies demonstrate and the number of lies that Fani Willis identifies being told to the American public about the election here in Georgia is that you cannot get your followers to be riled up about an election or to have people believe that they have to go into the streets and protest for you, unless you tell them that they have been defrauded.

And so those lies served an important purpose. In order for Donald Trump to get, or attempt to get the general assembly to overturn the election or to get Brad Raffensberger to overturn the election, unlawfully, unconstitutionally. He had to make his believers, or his followers, believe in that big lie, believe in the election denialism.

And ultimately, I think, while this doesn't speak to the Georgia election probe, but it does relate to or tie the Georgia election probe to the D.C. case, right? Ultimately, people will not engage in political violence unless they truly believe something of national importance, that their citizenship is being taken away from them.

And so I think the indictment really quite brilliantly and quite in great detail, evidences all of this and really shows how our democracy. Was in peril and continues to be in peril unless justice is served.

BECKER: I want to talk about some of the schemes that you mentioned, because it was an interesting reminder in reading this indictment, saying, "Oh yeah, I forgot that happened."

One was the fake elector plot in Georgia. Can you remind us briefly of what happened there?

MICHAEL KREIS: So there was a plan to introduce, I think, a series of doubts or maybe one major doubt about who the proper electors were for the state of Georgia. And this was devised, or this plan was devised, in order to attempt to give former Vice President Pence the opportunity to reject the lawful electors from the state of Georgia.

And either accept the alternate fake electors or send the issue back to the legislature for a decision with the presumption that the legislature would then pick Trump favored electors or Trump supporting electors. These individuals signed documents. At the state capitol. They did so, they met at the state capitol, they were shrouded in secrecy, and they put their hand and their signature to documents saying that they were the duly elected and appointed persons under Georgia State law.

Representing the state of Georgia and were pledged to support Donald Trump. Now, these are all false statements. There was no, at this point, doubt that the election was Joe Biden's victory and Joe Biden had won Georgia. At this point, we had the three different counts and the certified election results were really unimpeachable.

But nonetheless, these people gathered together and swore that they were officers of the state, essentially, authorized under our election code when they were not. And so that is a huge part of this indictment because in many respects this kind of fraud was essential in order to at least introduce enough doubt into the process that Donald Trump thought that he could take advantage of in order to basically deprive Georgians of their fundamental right to vote and their fundamental right to have their ballots counted accurately.

BECKER: I want to bring someone else into our conversation now. Chris Timmons is a trial attorney at Knowles Gallant Timmons, which is a law firm based in Atlanta. He served as a Georgia prosecutor for more than 17 years in DeKalb and Cobb counties. Chris, thanks for being with us On Point.

CHRIS TIMMONS: Hi, Deborah. Thank you. It's a pleasure to be here.

BECKER: So I'm wondering if we could start with you as well, what do you think, you've been listening, and we asked Anthony this, as well. What's the main thing we need to know about this indictment? Would you say?

TIMMONS: There are several things that you need to know.

One is, it is a sweeping narrative indictment. Your typical indictment in Georgia is going To be a short indictment. I've tried murder cases that are six pages long. This one is 96 pages long. I've also tried RICO cases. And so a RICO indictment in Georgia is a narrative indictment, meaning that it's allowed to tell the entire story, typical murder indictments or speeding or an armed robbery indictment's going to be shorter than that.

The other thing that I think about it that's important is that it has 161 acts in furtherance of the RICO conspiracy. And that's a lot of acts to prove when you get to trial. Now, the interesting thing and something that your reader should know, is that those acts in furtherance of the conspiracy are not necessarily criminal acts, right?

You've got some in there that are criminal. You've got some in there that would not ordinarily be crimes. And so the best analogy that I can use is, if you and I, Deborah, get together and we decide we want to rob a Bank of America, you're going to be the getaway driver. I'm going to be the gunman. We are going to take certain steps before that, that aren't crimes and furtherance of our conspiracy.

Advertisement

You may go rent a car, I'm going to go buy a gun. Neither one of those things are illegal acts, at least here in Georgia. It's not illegal to buy a gun. But if we bought them in furtherance of our criminal conspiracy, then they become a part of that crime of conspiracy. And we've committed a crime at that point by taking that overt act.

BECKER: And that is why we have this far-reaching 98-page RICO indictment that names 19 people, including former President Trump.

Part II

BECKER: Today we're talking about the latest indictment of former President Donald Trump. He faces his fourth indictment this year. We're talking about the nuances of the charges in this indictment and how they differ from previous allegations. Joining us to talk about this Anthony Michael Kreis, assistant professor of law and political scientist at Georgia State University College of Law.

Also, Chris Timmons, a trial attorney at Knowles Gallant and Timmons. He served as a prosecutor for more than 17 years in Georgia. And gentlemen, before the break, we were talking about the narrative that was laid out in this indictment that uses the RICO Act really to allege that there was a large criminal enterprise here trying to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election.

And the narrative involves several schemes, as Anthony, told us to try to accomplish this overturning of the election results. One of them was the fake electors that we talked about earlier, but another involved Trump advisor, Rudy Giuliani, who is accused of making false statements in this latest indictment from Georgia, one of the specific allegations is that Giuliani made false accusations against Georgia election workers, Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss, and said that they were trying to rig the election. Let's listen.

RUDY GIULINI: Quite obviously, surreptitiously passing around USB ports as if they're vials of heroin or cocaine. It's obvious to anyone who's a criminal investigator or prosecutor they're engaged in surreptitious illegal activity again that day.

BECKER: Now that USB port turned out to be candy, a ginger mint, and there was no evidence of any election fraud.

In fact, Giuliani admitted in a recent court filing that his statements against Freeman and Moss were false. Anthony, remind us of this action toward Georgia's election workers, Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss, and how it's part of this indictment.

MICHAEL KREIS: So Rudy Giuliani and a number of other individuals came down to Georgia in early December 2020 and brought with them alleged videotaped evidence of wrongdoing at the State Farm Arena in Fulton County where the ballots are counted.

And as you said, he alleged pretty terrible things about Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss and their conduct. And of course, the Secretary of State's office looked into this information very quickly and fairly rapidly debunked it, that not withstanding, not only did Rudy Giuliani testify to the Georgia General Assembly, the Georgia Senate in particular, that this had occurred, but there was a mass media campaign through social media, in particular, where Donald Trump browbeat these poor election workers alleging fraud.

There's also someone who, a publicist for Kanye West, who was dispatched to Georgia in order to attempt to allegedly strong-arm Ruby Freeman into making statements that were false, that election of fraud existed in order to essentially, I suppose you could say that the idea was you should confess to this wrongdoing or else something bad will happen to you. So a direct threat of intimidation. None of this, again, I want to repeat this as often as I can, none of this was true. And so in Georgia law, it's unlawful to harass, harass, intimidate, interfere with election workers and their work.

And I think it's also very important that this was an essential part of the conspiracy theory and the conspiracy to commit election fraud here in Georgia. Because it really called into question many people's minds the legitimacy of the Fulton County vote. And the final thing I think that we really need to focus on is how deeply damaging this was and is to our democratic process.

Because we rely on people to work the polls. The elections don't happen themselves. And so it's really essential that this kind of justice is found so that people don't feel afraid to give their time and resources and work the elections.

BECKER: Let's talk about the legal strategy. We talked about some of the main points here, the main controversies really. Let's talk about the legal strategy. Again, we mentioned that this is a RICO Act case, 18 alleged co-conspirators. And I wonder Chris, if maybe you want to talk about this, is some of the thinking here that with this many people involved, maybe some of the lower-level folks who are named might flip and cooperate and be able to provide more evidence against some of those higher up the food chain do?

Is that part of the strategy?

TIMMONS: That's a minor part of it, because in Georgia, in every state in the United States, a prosecutor can't go forward on a criminal case unless they have probable cause to believe that the people committed a crime. So that's step one. And the other thing is they've got to make sure that they fit properly within the scheme or the conspiracy that's being alleged.

But certainly, when you put people in an indictment, and I started off with one, I think we had 45 defendants in a RICO case. We narrowed it down to 19 by the time we crafted the indictment, and then we ended up working our way up the chain and had plea deals with everybody from the bottom to the top.

And while you're watching this, typically when a Georgia indictment is created, and this isn't a part of the law, it's just how we do things here. But the most important defendant is at the very top of the indictment. The least important defendants are toward the bottom.

And so what we typically did in a case where we had, 19, 20, 45 defendants is we'd start at the bottom. We'd try to flip them to go against the next person and then the next person until you get to the top. Cases are really difficult to try when you flip the top defendant first, because then you've got them going into court and suggesting that all these crimes were committed by people that they told to go commit those crimes.

And juries just don't like that. But yeah, getting back to your question, it's not necessarily how the indictment is drafted, but once the indictment is drafted, the strategy definitely becomes, "Who can we flip and use as people to testify against the others?" One last thing I'll add before I cease, is that when you're talking about flipping people in a RICO case, you want them to plead to RICO.

You want them to admit that they were a part of the conspiracy. And so when I was working out cases with defense attorneys, I would never let them plead to other charges. I would always want them to plead to the RICO. So when they testified, they came in and would admit that they had committed racketeering, that they had engaged in a criminal conspiracy.

BECKER: And we should say RICO was designed to be used for organized crime, to tie a bunch of folks together in a criminal enterprise who may not have all been specifically working together, but certainly were part of this larger enterprise. And that's what's being done here, and I know it's been done before in Atlanta, so briefly, without getting into a law class here, but Chris, I'm wondering, explain to us how this act intended for mobsters, really, has broadened out to now be used in this case.

TIMMONS: Sure. And Deborah, you've got two law professors here. Anthony's a real one, and I'm an adjunct and I'm married to a law professor. So you're going to get a law school class.

BECKER: I'm going to get a law class whether I like it or not. (LAUGHS)

TIMMONS: And I'm sorry, we're going to try to back that off. But yeah, how it's been used elsewhere, and it's not just in Georgia, but also nationally, then the federal statute's a little bit narrower, actually a lot narrower than the Georgia statute. But most recently, you had the scandal involving the wealthy parents who were bribing coaches to get their children into highly selective universities.

And so federally that was used there, Kwame Kilpatrick, who was the mayor of Detroit, was prosecuted under the RICO Act as well. So those are two examples of white-collar crimes being prosecuted using the RICO statute. But you also see a lot of gang cases that are prosecuted using the Ricoh statute. Here in Atlanta, in Fulton County, the three most prominent RICO cases tend to be relatively recent. One is the not all that recent, but the Atlanta Public School's cheating case was a RICO, a white-collar RICO case. That was back in 2003. Currently, right now we've got going on the YSL or the Young Thug RICO case.

That's a gang case. That's a more traditional use of the RICO Act, and then you have the Trump indictment, as well.

BECKER: And so, but again, how is it that it's broadened out to be used in these white-collar cases? Anthony, what would you say about that? Is it a shift a bit?

MICHAEL KREIS: I think that what's most important here is that we don't really think of RICO and election law.

I also think though it's important that there's a parallel federal statute, which is used fairly often in the election law setting, and in fact what Donald Trump is charged under in the D.C. case it's called Section 241. It's a reconstruction error law that says you can't deprive people of their civil rights in a conspiracy.

And actually, in that federal statute, there's no overt act required in order to prove the case, you just have to show that people conspire to deprive people of their rights that are afforded to them under the Constitution, the United States Constitution, or under federal law.

And so I think while Georgia's RICO, it brings up these images of the mafia and things of that nature, there's a law professor, colleague at George Washington University, who in fact described Georgia's RICO as basically a very broad sweeping conspiracy statute, right? Not really RICO in a traditional way that would made many people think of it. I don't, I think that we might not think of it as being appropriate or maybe not typical for an election law violation, but it certainly fits in with the character.

I think of both what federal law already permits in the election law setting, and also it seems to be quite appropriate given the nature of the unlawful enterprise that was formed to overthrow the election.

BECKER: One of the things that I was curious about in reading this and even just hearing about it at first, is what is Georgia's jurisdiction here?

Now I get it right, that Georgia's election results were mainly contested, but the indictment names a lot of other states and we're talking about a national presidential election. I just wonder, and I am assuming that part of the defense will be to move this to federal court and out of Georgia, but I'm just wondering, will that be an issue here?

Will that be a question, Georgia's authority to really challenge what happened here on a national scale? What would you say about that, Anthony?

MICHAEL KREIS: Georgia first and foremost has very broad extraterritorial jurisdiction statutes that basically say that if any crime that is directed towards Georgia is formed in the state of Georgia, or partly outside the state of Georgia, Georgia can exercise jurisdiction. And I think, of course, the other thing to point out is that Georgia and the people of Georgia, while part of a national conspiracy to have our rights deprived from us, people reached into the state and did things that were unlawful under state law.

And I think that the state of Georgia and the Fulton County District Attorney's office has every jurisdictional right to vindicate the civil rights of the people of Georgia. And that's what this indictment speaks to. But the final point about the federal courts, there is a removal opportunity for Donald Trump.

For Mark Meadows, also for Jeffrey Clark, who was working for the Department of Justice in the Trump administration, to essentially claim that they're being charged criminally here in Georgia for acts that were either at the periphery or even at the core of their responsibilities as officers of the federal government.

So essentially the idea being that as president of the United States, or as a member of the Department of Justice, that people had, these folks had a duty and an obligation to ensure that the elections in Georgia were free and fair. And so if that is shown, right, and it's a fairly low threshold, to be clear, and the courts read it very broadly, this idea of what constitutes their official duties, then it can be brought into federal court, heard by a federal judge with a jury and paneled through a federal process. Although Fani Willis and the Fulton County DA's office would still be allowed to prosecute it, so that is certainly an option.

BECKER: Chris, what would you say about this? Potential movement to federal court. And also, one thing that you had mentioned earlier that I thought was really interesting as well, the more than 160 acts that are outlined in the indictment, you said these are not necessarily criminal acts on their own, but together they create this picture of a potential criminal enterprise.

Some of them are just tweets or calling a Georgia lawmaker to get another one's phone number. That, yes, I understand, may create this picture that there was criminal intent going on, but do you expect that these things will be whittled down and what effect can it have to name things like this in an indictment like this?

TIMMONS: So that's a lot to unpack.

BECKER: I know. That's okay. We'll get there. And I told you not a law class, so that --

TIMMONS: yeah, no, I know. Ask me a lot and then I'll tell you a little. So a couple of things there. With regard, you mentioned international earlier or national earlier, I've used acts in furtherance of a RICO conspiracy that were out of the United States.

That's perfectly fine. So it doesn't affect the conspiracy at all, and I don't think that's what the federal court will be looking to. What I do think the federal court is going to be looking to is one of the elements of removing a case from Georgia into federal court. Is whether it's under the title of their office, like whether it's under color of office.

And so the question is going to be when the federal court is looking at this, is was this Mark Meadows? Mark Meadows the guy, or was this Mark Meadows, Mark Meadows, the chief of staff for the President of the United States when he's doing the things that he's alleged to doing? And the same thing for former President Trump.

Was he acting as Donald Trump, the person, or was he acting as President Donald Trump, president of the United States when he was taking these acts. And so that's really the rub. That's really what you're going to hear argued when there before judge Jones in federal court.

BECKER: So that's the expected defense you would say and what about this potential?

Would there, would it also be a defense really to say that this indictment is criminalizing political speech?

TIMMONS: I think you're going to hear that. I'm not sure how much traction that's going to get, assuming this case gets back to state court it'll be a decision there. And so I don't want to give a law class on the First Amendment, that's more sort of Anthony's area than it is mine.

But it's different than what you think of traditionally on First Amendment. So when a good First Amendment defense is the 2 Live Crew case, which was a Supreme Court case, I believe that happened in the 1980s where they were being prosecuted for the lyrics based under the obscenity laws.

That was a First Amendment violation. Here, they're not being prosecuted for what they said, they're being prosecuted for RICO. But these are considered acts and further into the conspiracy. And as far as I'm concerned that's not a violation of the United States First Amendment, but that's going to be litigated elsewhere.

BECKER: And I wonder when we look at this indictment with the others, would this be looked at in isolation or do you think what we're seeing here is a bigger picture that any court is really going to have to consider, Anthony.

MICHAEL KREIS: I think that's a political question more so for the electorate than it is for any court or any judge trying to suss out what to do with these cases.

The most important thing that I think these cases will do in terms of the relationship to one another is scheduling. It seems to be the case that Fani Willis wants to try this very quickly. I think she has an overly ambitious schedule asking for a trial in the first couple weeks of March 2024.

Donald Trump is scheduled in March 25th to be in New York in a trial, so that's a pretty short turnaround time and probably unrealistic.

Part III

BECKER: I think I want to start with you, Chris, and we've alluded to this earlier in the show, but what do we expect former President Trump's main defense of the charges within this latest indictment from Georgia to be?

TIMMONS: I think they're going to be two. I think the first defense is, I think they're going to honestly try to prove that there was election fraud in the state of Georgia. Or at least make their best effort to. I think the backup is intent. I think you're always going to argue that, look, even if there was an election fraud in the state of Georgia, he thought there was and so that's the defense that I would raise if I was his attorneys.

That's the defense I'm going to raise in court. The defense is that I'm going to raise, when I'm in the court of public opinion, I'm going to talk about how Atlanta has a serious crime problem. Why are we wasting these resources with this YSL trial? Why are we wasting these resources with the Trump case? And so I think that's something that we're going to hear.

The other thing we're going to hear is that it's political. I don't believe that in the state of Georgia prosecutors should be partisan. But unfortunately, here they are. And so you have a democratic Fulton County district attorney if he's prosecuting a Republican political figure. And so there are going to be a lot of allegations, already have been allegations that this is a political situation rather than an actual proper prosecution.

And I guess the final thing I'd say is they're going to argue that they're treating him like a mobster when he is not. We hear that in every single RICO case, that, you know, that RICO should be reserved for organized crime. La Casa Nostra. It shouldn't be used in prosecuting political figures.

BECKER: One thing, also, one question raised by all of this is what might happen if former President Trump is reelected?

How would these legal proceedings go forward? That would be unprecedented Anthony?

MICHAEL KREIS: It would be. So there are a few different scenarios here that are important. If Donald Trump were convicted by some miracle of time, because time is really of the essence here. Before the election, and if for some reason the state of Georgia had him in their custody and Donald Trump was elected president, again, there is a very strong argument and I think it's almost an overwhelming consensus.

The state of Georgia would have to spring him loose in order to serve out his time as president of the United States for four years. That's very interesting because what it would not do is relieve Donald Trump of the obligation to fulfill his sentence after he finishes his term.

And I think a lot of political scientists would look at that and say that's a very dangerous dynamic. It is a kind of dynamic that it's often referred to as the dictator's dilemma. Do you let go of power or do you voluntarily give power back knowing that you are going to prison? That's a very dangerous moment for our democracy potentially.

The other thing that of course people are talking about is whether or not the pardon power would have any effect here in Georgia. So if Donald Trump became president, or if a sympathetic Republican to Donald Trump became president, they could basically wave away all the federal cases, either through the pardon power, and or dismissing the Department of Justice's case in D.C. and in Florida.

That's not true here in Georgia. In Georgia, the governor does not have the constitutional gift to issue pardons. Rather, it's the Board of Pardons and Parole. And basically, if Donald Trump was convicted, he would have to fill out his sentence, and then wait probably five years before a pardon would be available.

So it's a much more difficult task to get a pardon here in the state of Georgia for state crime convictions than it is in the federal level.

BECKER: So then all the more reason to try to move it to the federal level. Would that be an accurate interpretation there?

MICHAEL KREIS: No. If the case gets removed to federal court, the idea there is that it's a more neutral venue that we don't necessarily always want federal officials to be tried in state courts.

So think for example and these are not akin, these are not like examples, but think for example, a southern state in the '60s. Trying to prosecute a federal official for enforcing civil rights laws. You could see that dynamic happening. You wouldn't want that case in a state court because of the kinds of prejudices that would be introduced there by the local judges, local juries and the like.

And so the federal court would be a more neutral place, an appropriate place for that. And that's the theory behind the removal statute. But at the end of the day, if a conviction is rendered in that case, it's still a violation of state law. And so the state law pardon process would apply even though it played out in federal court.

BECKER: Interesting. I also think I want to talk bigger here about what you think this means overall for the country really and for democracy. I think a lot of folks are saying, "Is Georgia the worst here?" Is this the biggest sort of, most involved really sordid story of what might have been happening at the time? And how do you think, Anthony, this affects the White House and politics going forward?

MICHAEL KREIS: Georgia really was at the epicenter of Donald Trump's fixation with the 2020 election results. By all accounts, from the Jan. 6th report and from some other reports, it just seems to be the case that Donald Trump could not let go of the idea that he did not win Georgia and Joe Biden did. And I think part of the reason for that is because Georgia was able to, Georgians were able to muster a multiracial coalition in particularly gravity, with gravity or the center of gravity being in the Atlanta metro area.

That really challenges the status quo in many ways. And Donald Trump doesn't particularly seem to care for being challenged by Black political power in particular. And I think there's a reason why Donald Trump attacks places like Atlanta or Detroit or Philadelphia or Baltimore or Washington, D.C., and questions the citizenship capacity of the people who live there and their ability to self-govern.

I think the kind of racial politics here are really important, but that really hearkens to something that's more important or a point that I think we can't lose in this discussion about the health of our democracy. Right? Big changes often times create a lot of blowback. People, some people tend to lean into anti-democratic impulses when the status quo is challenged, particularly when there are racial politics involved.

That is a lesson of reconstruction, right? There was a lot of election denialism in reconstruction. That election denialism fomented a significant amount of political violence. But importantly, in reconstruction, nobody was held to account for their election denialism and the political violence that developed out of that.

And I think Fani Willis has to, and Jack Smith for that matter, have to really look back to that history and use it to justify using the criminal justice process to prosecute these election law crimes. Because at the end of the day, when people think that they can get away with tearing democracy from out from under voters and to trample on the rights of voters and the rights of citizens they will feel emboldened to do it again, and that is simply anathema to a healthy, modern democracy.

BECKER: So we should be using the criminal justice process, in your opinion.

MICHAEL KREIS: I think so. I would have personally preferred the impeachment process to take care of this, really. The United States Senate, and I will say Republicans in the United States Senate, chose not to convict Donald Trump and chose not to, also, after a conviction, impose a disqualification of office on Donald Trump, we could have taken Donald Trump out of the body politic. Without turning to the criminal justice system, but it was Mitch McConnell who said, we should just let the criminal justice system take care of this. That's the option we've been left with by Senate Republicans who refuse to convict Donald Trump for his impeachable offenses on Jan. 6th, 2021.

BECKER: Earlier this week, former federal judge Michael Luttig told the PBS NewsHour that former President Trump's effort to overturn the 2020 election has had a real devastating effect on the country. And I want play a little clip of that.

Let's listen.

LUTTIG: For four years, these claims by the former president and his Republican allies have corroded and corrupted American democracy and American elections. Vast numbers of Americans into the millions, today, no longer believe in the elections, the institutions of law and democracy in America.

BECKER: So that was former federal judge Michael Luttig. And Chris Timmons, I want to ask you. Do you feel that we have entered this era where a vast number of Americans as Judge Luttig says, no longer believe in the institutions of law and democracy and this goes to the point of using the criminal justice system in this particular case.

I wonder if you could share your thoughts on that with us.

TIMMONS: Sure. You hope the criminal justice system isn't politicized, no matter how good or how noble the goal. But in terms of the justice system in America, I think I read an article the other day that talked about, we peaked as a civilization in about 2010 when we created Google Translate and we could all communicate across the globe. And that we've regressed dramatically in the past 12 years, because we're living in two different realities depending on what the political parties are. One group of people believe that vaccines are just fine.

Another group believe that they're the most evil thing on the planet, and it doesn't matter what information you give to a number of people, the cognitive bias is so strong, they're going to believe it, whether it's there or not. So I think it's definitely, Anthony could speak better to this than I can, but I think we're in a dangerous time as a democracy.

But, you hope, and I'm an optimist, we've survived dangerous times before, we got past a civil war. We got through the Watergate impeachment; the president of the United States resigning is unprecedented. So we're back in one of those eras. But I certainly hope that we recover, that we can begin to have those discussions again about politics without everybody getting upset and having to leave the Thanksgiving Table.

BECKER: Right. Oh, yeah. Okay. Let's talk about just politics in the polls. Anthony, what do the polls say about how these indictments are affecting former President Trump in his efforts to get reelected?

MICHAEL KREIS: There's a big difference between the Republican primary electorate right now and the average American voter.

It seems to be the case that every time Donald Trump gets indicted, that his support among Republican primary voters is more concrete, if not growing. And it seems to be that very few Republican candidates can gain traction on Donald Trump right now. But there are a number of polls, and I do want to really stop for one second and say, "Polling, of course, is not indicative of guilt or innocence, right?

We still have to prove whatever, by we, the people of Georgia, right? Because this has been brought in our name." But what has to be proven is the evidence beyond a reasonable doubt. The presumption of innocence is not tied to polling, but polling shows out today that over 60% of Americans believe that the allegations made in the Fulton County case are serious.

And a plurality, almost a majority, believe that the case should be brought. And I think that's important. And I think that the really valuable aspect of the Fulton County case perhaps, and perhaps the reason why it should happen before the election and maybe before all the other cases, in fact, is because if it remains in the Fulton County Courthouse, we will have cameras.

We will have video; we will have YouTube channels streaming this trial. And it's important, I think, for the American public to see it, to weigh this evidence for themselves and to really stop in the human cry of this moment. And ask people to say, "Okay, here's the evidence that Fani Willis has put forward before the people of Fulton County, before this jury, but before the entire nation and the world to see and to evaluate, what do we do with this?"

And that's an important national dialogue. And I an important point for potential national healing and progress that can't be done behind the shroud of secrecy that federal courts operate in. And that makes Fulton County very different.

BECKER: But realistically, could this really get to trial and be televised before the next election?

MICHAEL KREIS: No, I understand why the District Attorney's office here wants to expedite the process. I truly do, but if we look at other, Chris has talked about the YSL trial, it has been just replete with drama and chaos and delays.

BECKER: And isn't it like an eight month long jury selection process So far?

TIMMONS: It's still going.

BECKER: Still no jury, right?

MICHAEL KREIS: Still going. Yeah. And the other thing is it's really hard, especially for a case, who knows how long it'll actually last. But for some of these cases, and by the way, it makes it more complicated now because people will always ask for hardship exceptions in jury service because they want to get out of it.

But right now, there are reports that the grand jurors whose names are public in Georgia on an indictment, information is being released about them and there are people who seem to be willing to engage in. I think patently unlawful intimidation of these folks for doing the service that they have been commanded by law to do.

They're not doing this voluntarily. And so that's a really difficult position to put people in and that's only going to complicate jury selection. And I just think there are so many different variables here that getting this trial in March is unrealistic.

TIMMONS: It's not going to happen.

BECKER: And Chris, it's not going to happen. We've got a minute left here, just very briefly. What are we waiting for next? Arraignment, I presume. And once arraigned, could any of these defendants be held? So the next thing is they're turning themselves in. Arraignment will come after that. But certainly, they could, I think it's unlikely.

I think holding Donald Trump in the jail would be miserable. They'd probably have to clear off an entire floor. But getting back to what Anthony said, I think jury selection is everything. I'm teaching that class tonight at 6:00 PM and so this case rises and falls on the 12 people that will make the decision.

This program aired on August 17, 2023.