Advertisement

Can the Korean Armistice Agreement serve as a model for peace in Ukraine?

Observers around the world are increasingly asking whether the conflict in Ukraine has reached a stalemate.

More than 70 years ago, the Korean War was on a similar path.

“Both sides couldn’t really break the stalemate. And the United States fought fairly well there and really prevented the Chinese and the North Koreans from gaining any more ground," Carter Malkasian says. "But it wasn’t possible to make ground to win the war decisively.”

So, what can the Korean Armistice agreement teach us about achieving peace in Ukraine today?

Today, On Point: Can the Korean Armistice Agreement serve as a model for peace in Ukraine?

Guests

Carter Malkasian, chair of the Department of Defense Analysis at the Naval Postgraduate School. Author of "The Korean War: 1950–1953."

Jong Eun Lee, assistant professor of political science at North Greenville University.

Transcript

Part I

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: It’s been a year and a half since Russia launched its invasion and attack on Ukraine. Russian forces have taken control of the Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia regions of Ukraine. But in the past several months, the war’s frontlines have not significantly shifted.

And analysts have been asking: Is the war at a stalemate?

JOHN KIRCHHOFER: Certainly, we are at a bit of a stalemate. We do see incremental gains by Ukraine as they commit to this counteroffensive over the summer, but we haven’t seen anything to really help them breakthrough – you know, for example, to drive to the Crimea.

CHAKRABARTI: That’s John Kirchhofer, Chief of Staff for the Defense Intelligence Agency in July.

But just days after Kirchhofer’s comments, White House National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan went on ABC News insisting that the Biden Administration does not officially see a stalemate on the ground in Ukraine.

Advertisement

JAKE SULLIVAN: We said before this counteroffensive started that it’d be hard going. And it’s hard going. That’s the nature of war. But the Ukrainians are continuing to move forward, and we’re continuing to supply them with the necessary weaponry and capabilities to be able to do that. And they will keep attempting to take back the territory that Russia has illegally occupied, and we will continue to support them in that.

And just this Wednesday, the U.S. re-upped its support of Ukraine during Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s surprise visit to Kyiv.

ANTONY BLINKEN: The United States is committed to empowering Ukraine to write its own future. In the crucible of President Putin’s brutal and ongoing war, the United States and Ukraine have forged a partnership that is stronger than ever and growing every day. We will continue to stand by Ukraine’s side, and today we’re announcing new assistance totaling more than $1 billion in this common effort. That includes $665.5 million in new military and civilian security assistance. In total we committed over $43 billion in security assistance since the beginning of the Russian aggression.

CHAKRABARTI: The announcement comes as Ukraine says it’s had a breakthrough in the South – the toughest line of the war. Ukrainian officials say they’ve reclaimed Robotyne, a village in the Zaporizhzhia region.

But with little time before the fall rain and the winter snow, analysts say the situation is likely to lapse back into stalemate. This is On Point. I’m Meghna Chakrabarti.

Whether history echoes or rhymes, there’s a shimmer of familiarity between stalemate between Ukraine and Russia, and another grinding conflict that’s now 70 years old.

The Korean War.

(KOREAN SPEECH BY KIM IL SUNG)

CHAKRABARTI: (TRANSCRIPTION) “On June 25, the army of the traitorous Syngman Rhee clique launched an all-out offensive against the northern half of Korea,” declared North Korean leader Kim Il Sung in a radio address, June 26, 1950.

He went on to say “… The Government of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, having discussed the situation, ordered a counter offensive action and wiped out the enemy’s armed forces.”

But historical accounts state a different story. That it was North Korea that launched the war when approximately 75,000 soldiers from the North Korean People’s Amy crossed the 38th parallel to invade South Korea.

The Korean War devastated the peninsula. At least two million civilians were killed between both North and South Korea over the next three years.

And the brutality of conflict was exacerbated by the fact that China and the Soviet Union backed the forces in the North, led by Kim Il Sung, while the U.S. and its Western allies supported the South, led by Syngman Rhee. Foreign nations poured troops into the war, including 1.8 million Americans who served on the ground.

PRESIDENT HARRY TRUMAN: 52 of the 59 countries which are members of the United Nations have given their support to the action taken by the security council to restore peace in Korea.

CHAKRABARTI: The frontline ebbed and flowed in the war’s early stages. Until the conflict reached a stalemate along the 38th parallel. That border would later become the Demilitarized Zone – or the DMZ. Today, it continues to mark the barrier in Korea’s frozen conflict 70 years later.

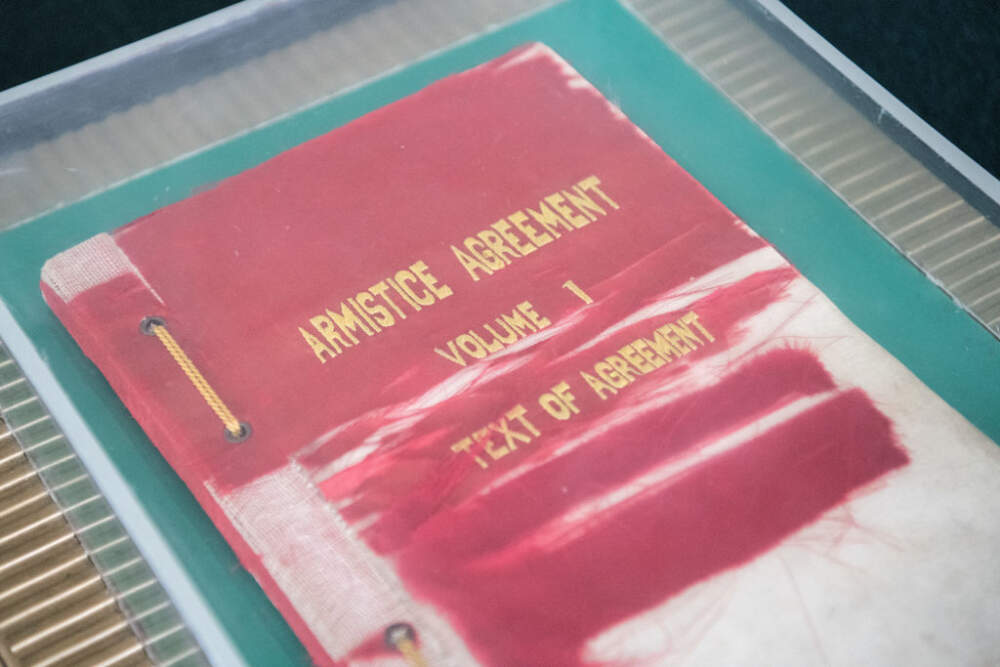

A peace, though imperfect, brought about by the Korean Armistice Agreement, signed seventy years ago, July 27, 1953.

From the potential stalemate to the complex relationships between the countries fighting the war and their outside allies – if there’s a parallel between the conflict in Ukraine and the Korean War, could the Korean Armistice Agreement also offer an example of one way to end the fighting in Ukraine?

That’s what we’re asking today.

Joining us now is Carter Malkasian. He’s the Chair of the Department of Defense Analysis at the Naval Postgraduate School. He’s also a historian and the author of "The Korean War: 1950–1953." Professor Malkasian, welcome to On Point.

CARTER MALKASIAN: Hello, Meghna. Thank you so much.

It's great to be here.

CHAKRABARTI: So tell us, if you were to compare the current moment in the Ukraine war, the stalemate that we described earlier, to the timeline of the Korean War, where would you point to in the Korean War? Right now, it would be the part of the Korean War in 1950. Right before or somewhat before negotiations start.

MALKASIAN: Negotiations in the Korean War start at the beginning of July 1951. The war of course starts in June 1950. So you're almost, you're a year into the war by the time negotiations start. That would be about the approximate time that I'd say we are at, because we don't have negotiations started yet. At Korea at that time, there had been severe fighting that had been happening.

The United States had driven into North Korea in early in 1950, and then in late 1950, the Chinese had entered the war and driven us back south, and we had slowly managed to climb up to the 38th parallel. And a stalemate was just starting to get put in place, but the fighting was extremely heavy at that point.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so I want to just focus for a moment on the Chinese offensive that you just talked about. We have a little bit of historical tape here. In the spring of 1951 as the professor just said, Chinese forces launched an expected spring offensive. And here it is captured by a TV documentary series called The Big Picture.

NEWSCAST: During the period 20 April to 20 May, the Communists launch two phases of their expected spring offensive. On 23 April, the Reds jump off on their first phase, hitting strongest above Seoul. UN troops are forced to withdraw south, as British and Belgian contingents hold off the Communists in a spectacular rearguard engagement.

A secondary action of this phase hits in the Hua Chan Reservoir area. By 30 April, UN forces cease their withdrawal and set up the Lincoln Defense Line a few miles north of Seoul.

CHAKRABARTI: So again, that's from 1951. Now I want to note one obvious difference between these two wars, and it comes in the form of the fact that we're already talking about foreign troops that were fighting alongside both North and South Korean forces in the Korean War.

We don't have that yet overtly in Ukraine. But Professor Malkasian, can you tell me more about what happened in that fifth phase offensive? Given the posture of both China and the USSR at that time, how did it change Mao and Stalin's perception of the war?

MALKASIAN: Great question. Absolutely. So when Mao intervened in the war, in late 1950, he saw quick successes and his strategy became one of attempting to retake the entire peninsula and to drive the United States out of it.

He kept that goal throughout early 1951, and that fifth phase offensive that we spoke about was an attempt to reach that goal again, to drive the United States well off the 38th parallel and to retake the whole peninsula. So it was really a major event. But in that battle, his forces suffered and the Korean force, North Korean forces suffered over 85,000 casualties.

We don't know the exact figure, but it was quite large. And while they got a little bit of ground, the U.S. counter offensive and the South Korean counter offensive was very devastating. And once Mao had seen that he couldn't take more ground and he had taken such losses, that forced him or highly compelled him to come to the negotiating table.

And Stalin at that point also agreed, "Okay, it's time to come to the negotiating table." Trying to take over all of Korea isn't any longer feasible. Let's think about talking a bit.

CHAKRABARTI: So then, are there any echoes or shimmers, as I said a little bit earlier about what it took for Mao and Stalin to decide to come to the negotiating table versus where things might head in Ukraine? Because I do want to underscore your point.

There is no negotiating table yet.

MALKASIAN: I think that the key point is here that as the battle keeps on going, both sides are facing greater costs, and that can make negotiations more palatable. So while we don't have a fifth phase offensive kind of event right now, we do have continued stalemate and continued losses, and that can press people to come and negotiate.

I think it also really emphasizes, though, that if we want to get to negotiations, it does mean the United States and the other NATO allies and other countries have to keep on backing Ukraine, have to keep on giving them arms, have to expect that we're going to have to give them arms over a good period of time.

Because if Ukraine cannot maintain its position, if they can't maintain the stalemate and some degree of pressure on Russia. Then it's unlikely Russia will decide to negotiate that military pressure becomes very important, even as that military pressure is tragic because of the number that will be live lost number of lives that will be lost in the course of it.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: We're looking back at the Korean armistice agreement and asking whether that document and the circumstances around its creation could provide any sort of way forward for the current stalemate between Ukraine and Russia.

Carter Malkasian is with us today. He's chair of the Department of Defense Analysis at the Naval Postgraduate School. Also author of the book, "The Korean War: 1950 to 1953." Now I want to talk in a second about the actual terms of the armistice, but Professor Malkasian, I'm curious. Again, just to test our, continue to probe and test our theory here about how much history echoes, how do you think the two wars compare regarding what triggered them, what the goals were and are for, say, Russia and North Korea versus Ukraine and South Korea?

Just the overall thrust of both of these major conflicts.

MALKASIAN: So I think there's, when you talk about the goals there's some similarities there. As far as we know, Russia went into Ukraine attempting to take all of Ukraine. So that's a distinct similarity that's there. It also seems possible that there's a similarity that Russia may peel back its goals and may be willing to accept something less than that.

Certainly, in reality, if not necessarily writing it down and saying that they're accepting something different. In terms of the other side, we have Ukraine on the defensive as South Korea was on the defensive. Ukraine having already lost some territory and being a bit interested if it can get off the defensive to get that territory back. Syngman Rhee in South Korea and many South Koreans were interested in the same thing during the war to be able to not just get the 30th parallel, but all of Korea back. So there's some distinct similarities there. A few differences. The aggressor in the case of the Korean war was North Korea.

China eventually comes in on their side, and Stalin, the leader of Russia at the time, had been backing it, giving arms, and in fact, there were 500 or more Soviet pilots flying in support of the North Koreans, and often battling our own Air Force pilots. So that's a difference, in that Russia in this case is much more alone.

Even if China might be giving them verbal backing, no one thinks that Xi Jinping is giving the kind of support that Stalin gave to Kim Il Sung. And the other difference is the one that you mentioned earlier. The Ukrainians do not have U. S. forces on the ground assisting them. They do not have other international or NATO forces on the ground assisting them, whereas that was the case in Korea.

And that means the amount of pressure that Ukraine can bring to bear is much less. It also, oddly, means that the amount of pressure that we can bring upon Zelenskyy to come to the negotiating table is less. Because we have less in the game.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. So there's another maybe subtler comparison I want to make in terms of I hate to say this, emotional, but primal reasons why these conflicts have occurred.

And check me on this, but one can look at the Korean War as Koreans fighting Koreans, right? The North had said it wanted to reunify the peninsula, create a unified Korea. Whereas Russia is invading Ukraine. Two very different nations. But the Russians say, Putin and those surrounding him, I've read quotes of Russian leaders saying Ukraine isn't even a country, right?

That it's always been Russian. And that not only for security reasons, but for reasons of the strengthening and expansion of what they already see as the Russian nation, their cause is just. So are there similarities there? And the reason why I ask is because I think those things really end up mattering when parties come to the negotiating table.

MALKASIAN: I think there are similarities in that regard, especially in terms of how the Russians view Ukraine and how they can see it as a single country. And there's also, again, a similarity there in terms of the Ukrainians are going to feel that same kind of deep passion that you mentioned about retaking parts of Ukraine.

So that is going to be deep on both sides. And that may be one of the reasons why an armistice situation that establishes a ceasefire may be more palatable in the end to both sides than an official political settlement where you'd have to get into the very issues that you just spoke about.

CHAKRABARTI: Ah, that's interesting. So hold that thought cause we're going to come back to that. So let's dive a little bit more into the armistice itself. And in just a moment, we're going to bring in another voice, a Korean voice into this conversation. But the armistice, the Korean armistice agreement was signed in Panmunjom, Korea on July 27, 1953.

A short time later, it was nighttime July 26 in Washington, President Dwight Eisenhower broke the news to Americans on national television.

PRES. EISENHOWER: My fellow citizens, tonight we greet with prayers of thanksgiving the official news that an armistice was signed almost an hour ago in Korea. It will quickly bring to an end the fighting between the United Nation forces and the communist armies.

CHAKRABARTI: Eisenhower said that the armistice was not the culmination, but the beginning of peace in Korea. The president noted that there was much more work to be done.

EISENHOWER: Throughout the coming months, during the period of prisoner screening and exchange, and during the possibly longer period of the political conference, which looks toward the unification of Korea, we and our United Nation allies must be vigilant against a possibility of untoward developments, and as we do we shall fervently strive to ensure that this armistice will, in fact, bring free peoples one step nearer to their goal of a world at peace.

CHAKRABARTI: To signify the United States commitment to completing the terms of the armistice, Eisenhower looked to another leader who guided a nation through a war that divided its people. He quoted Abraham Lincoln's second inaugural address.

EISENHOWER: With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in.

To do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations, this is our resolve and our dedication.

CHAKRABARTI: President Dwight D. Eisenhower on the night of July 26, 1953. Joining us now is Jong Eun Lee, assistant professor of political science at North Greenville University.

He also served as a South Korean Air Force intelligence officer from 2011 to 2014. And he joins us from Tigerville, South Carolina. Professor Jong Eun Lee, welcome to On Point.

JONG EUN LEE: Hello.

CHAKRABARTI: What would you say are the most important terms of the Korean Armistice Agreement, let me say, were the most important terms of the Armistice Agreement then, in the summer of 1953?

LEE: I would say in summer of 1953, from the perspective of the South Korean government, two important components was one, U. S. reassurance that U. S. will sign the Mutual Defense Treaty with South Korea. That was one very important component. And number two, interestingly, ambiguity on the duration of armistice, that it appeared as if, from South Koreans perspective, that armistice is not going to be permanent, and that there might be certain pathway for South Korea to achieve reunification in the future.

Either peacefully or by resumption of military force.

CHAKRABARTI: So can you tell me more about that? Because I suppose that's a part, that's one of the aspects of why I called the armistice 70 years later a piece, but an imperfect one.

LEE: Correct. So for the South Korean government, they did not want South Korea's division to become permanent. And therefore, If the armistice was going to become permanent, that means that South Korea would relinquish permanently its control over all the territories north of the 38th parallel, which South Korean government was not willing to accept.

So their demand on the United States was if the armistice is signed, and there's going to be a post armistice conference afterwards in Geneva, they ask, "What will U. S. do if post armistice conference fail to provide any diplomatic solution for Korea's unification?" South Korea's government's position was, if post armistice conference fails, then U.S. should support South Korea to engage in — South Korean phrase is Bukjin. Bukjin, which means advanced north. The South Korea should have the right to resume the war with U. S. support as South Korea's ally. That was a key demand in which U. S. had to respond wisely, prudently, and ambiguously.

CHAKRABARTI: Yes, so Carter Malkasian, how did the U.S. respond to that South Korean demand?

MALKASIAN: The United States' position was there would be political conference, a political conference and conferences to follow the armistice that occurred. Now, unfortunately, those conferences, as we now see, led to no further political settlement, which meant that the armistice, the ceasefire simply stayed in place. Now, of course, it was also a very imperfect ceasefire with lots of skirmishes and such. The United States tried to reassure, had reassured South Korea with security guarantees and with a treaty alliance to encourage South Korea to agree to the armistice in the end.

Advertisement

But of course, in the final days of the war, Syngman Rhee was quite opposed to the armistice. And, in fact released 27, 000 prisoners on his own, which went against some of the initial terms of the armistice. And so there had been a great deal of friction that had occurred, and the United States had to go through some very difficult diplomacy to convince Syngman Rhee that it was worthwhile to go forward with the armistice.

And that included some of these security guarantees and an alliance.

CHAKRABARTI: I see. And just to remind folks, Syngman Rhee, as we're talking about, leader of South Korea at the time. Professor Jong Eun Lee, is that one of the things that explains why the creation of the armistice and the agreement on the terms took so long?

Because as Professor Malkasian said a little while ago, negotiations began in July of 1951, but it wasn't until two years later that it was signed.

LEE: Correct. I recall that the commander of the U. S. Army, or I guess I should say the U. N. command forces in South Korea, by the name of General Mark Kirk, he later wrote in his memoir that he felt as if he was fighting a war on two fronts.

One, with the communists, but with a whole different front with the South Korean government in which the armistice negotiations had to take place trying to convince communist negotiators to accept the armistice and convince South Korean government to accept the armistice terms as it is.

CHAKRABARTI: I see. So that's some of the tensions between the United States and South Korea that made this process take so long. And just I remind myself that in those two years, millions of people were dying. because the war was hot and very active on the peninsula. On the other side of the table, Professor Malkasian, can you tell us about how North Korean leadership, but also particularly Mao and Stalin were talking about their ideal terms for an armistice or coming to the table?

MALKASIAN: Yeah, absolutely. When negotiation started, Mao and Stalin and Kim Il Sung, they thought we don't have to make an agreement quickly. We have numerical superiority. The Americans and the South Koreans are going to take a lot of casualties, so we can work this slowly. And the fighting continued, and they had to, they had difficulty maintaining that position.

First, they had to concede to a ceasefire line that was along the line of control, which meant that where forces were at the time, which was a little bit north of the 38th parallel. So they had to back up a little bit on that. And then over the course of 1952, North Korea and eventually China become under more and more military pressure.

Like you mentioned at the beginning, there was a large amount of devastation in Korea. So that included bombing of Pyongyang, included hitting of hydroelectric plants that produced electricity, damage to farming fields occurred. That puts a lot of pressure on Kim Il Sung. So Kim Il Sung in the middle of 1952 starts talking to Mao and talking to Stalin and saying, "Hey, could we think about maybe finding a way out of this because I'm coming under a lot of pressure." At the same time, China was also under pressure, not as bad, but their economy was getting repressed because of the fighting that was going on.

You have to remember the Korean War started under a year after the civil war in China had ended.

CHAKRABARTI: Ah, that's right.

MALKASIAN: So this was a very, difficult political time for Mao, so he's also suffering losses. The problem was Stalin when it came to negotiations, Mao sends his premier, Zhou Enlai, to Moscow in August of 1950, in 1952.

Zhou gets there and they have to talk about, they have to talk about a whole lot of different topics. There's a whole lot of arms agreements and diplomatic things to talk about. But one thing that Zhou is trying to figure out is what is Stalin's position on coming to an end to this war. So he sits down, he has a first sitting with Stalin, and in that conversation, he tells Stalin, "Hey the battlefront is a stalemate. It's going to be hard for us to progress a lot further. But we're confident and we know we can beat the Americans in the end." And Stalin says, "Yes, that's right we're going to this is a good position for us." And in that same conversation.

CHAKRABARTI: Oh, no, I was just going to say, he didn't sound interested, having, as in having any interest in ending the war.

MALKASIAN: That's right. And at the end of that conversation, Zhou comes back to him and says, "The North Koreans are under a lot of pressure, and this is coming a little bit difficult. Some of them are panicking even." And Stalin says, "Look, I've already heard about that. I've already been briefed on that."

So he brushes them off. There's a second meeting that occurs about two weeks later, where Zhou again brings up what if there was possible to have a concession on some of these points particularly regarding prisoners that could bring an end to the conflict. And Stalin says, "Yeah, that could work, I don't think we want to go that way."

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: Today we're looking back seven decades to the Korean War and the stalemate that led to the development and signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement, 70 years ago in 1953. And we're wondering if that moment in history can provide any guidance or light on what might happen next in the conflict between Ukraine and Russia.

Now, we were talking about the role that Mao played in China, that Stalin played in the Soviet Union, that the United States and Western allies were playing in terms of their alliance and support of South Korea. The Korean Armistice Agreement process took two years — two years — to finally reach a point where both sides would sign.

But the trajectory of the war and the armistice process was changed in 1953 by an unexpected death.

NEWSCAST: When, from Moscow, news of the stroke that ended Stalin's life spread round the world, it was all the more startling because so unexpected. Now, Moscow mourns a man who rose from humble origin to rule from the splendor of the Kremlin, holding its way not only over the USSR, but also over the satellite countries.

CHAKRABARTI: Professor Jong Eun Lee, Joseph Stalin suddenly dies. How did that change the trajectory of the armistice process? Because as Professor Malkasian was saying earlier, it didn't seem as if Stalin had any desire to end the Korean War. So if he had stayed alive, what path would have the conflict taken, you think?

LEE: I find the deaths of Stalin fascinating because it brought two different reactions, opposing reactions. On the one side from the communist side, so from China and North Korea, deaths of Stalin, as professor Malkasian mentioned, it provided finally flexibility on the part of communist negotiators to become more open.

To negotiating armistice with the U.S. side. So back then, one of the remaining hot button issue was returning the communist prisoners of war back to North Korea or China, in which U.S. demanded the right of conscience in which communist prisoners of war could either decide to stay in South Korea or return back to the Chinese or North Korean army.

After the death of Stalin, communist negotiators finally became much more flexible and willing to compromise on this issue by agreeing to U. S. offer that perhaps near Panmunjom, some of the neutral nations could send representatives to interview. Screen the communist prisoners to decide whether they truly want to return back or stay in South Korea.

So communist delegations became, they moderated their positions in the armistice. That's one consequence. On the other hand, it actually made the South Korean government more nervous. Because South Korean government was actually hoping that armistice was just last forever without any outcome, any success.

U. S. see the futility of reaching any negotiations, to suspend the negotiations and resume military operations. That's what South Korea was actually counting on for a year and a half or almost two years. But then suddenly seeing that communist negotiators could actually agree to armistice. That actually made South Korean government more worried because they didn't want armistice to happen.

So you will notice that South Korea's anti armistice protest and South Korean National Assembly's furiously passing resolutions declaring no to armistice, that intensified in the spring of 1953, after the death of Stalin.

CHAKRABARTI: I have to say my profound gratitude to both of you. Because this level of detail never came up in my high school or college history courses when we studied the Korean War.

This is utterly fascinating. Okay, so for the range of the show, let's pull these points, these lessons now into the present with Ukraine, Russia and what may happen there. Carter Malkasian, let me start by asking you, look, I'm hearing that there are, of the many critical points that led to the signing of the Korean Armistice, there's a couple that I'd like to focus on.

We just talked about Stalin's death, so perhaps the analog would be what would happen if Vladimir Putin would die. We can't know if that's going to happen or not. The other things about what was in the armistice itself, the request for the mutual defense pack, that's the pact, I should say, that South Korea demanded from the United States. I assume the analog there would be Ukraine's entrance into NATO.

Which is a non-starter for Russia at this point, because that's one of the very reasons Russia says it invaded Ukraine. And also South Korea is seeking agreement for eventual reunification. I'll be honest, Professor Malkasian, I'm not actually seeing many points of enough resonance here that would convince me that the Korean Armistice Model would be potentially an effective one in Ukraine.

MALKASIAN: One thing is that the Korean Armistice Model is an option amongst other options. I think it may be the best of a selection of poor options on what to do, not necessarily something that is guaranteed for success. And I think it's very important to underline that there is no guarantee here and we need to be very sober about what possibilities are. That said, in terms of an actual treaty, NATO agreement with Ukraine, that degree of commitment may not be necessary. Other forms of security guarantees of continued military assistance, possible placement of non-combat advisors inside the country on guarantees of economic assistance.

That can encourage Ukraine to be willing to step forward and to make an agreement. So I think there are still guarantees to pressure things in that way. The armistice is a gamble in terms of will Putin concede or not? Because Putin is the equivalent of Stalin here. The recalcitrant leader who could stop it all from happening.

But all that said, an armistice that establishes a ceasefire, some supervisory arrangements and has international backing is a better course in Ukraine than either hoping for military victory or letting it settle into a frozen conflict in which Putin is free to do whatever he wants to do, on down the road.

CHAKRABARTI: Let's listen to a moment from Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. In July of last year, he spoke to independent Russian journalists about the criteria that would make him, quote," Ready to discuss neutral status in a potential Ukraine-Russia peace deal.

ZELENSKYY: Security guarantees and neutrality, the non-nuclear status of our state, we are ready to go for it.

This is the most important point. It was the main point for the Russian Federation, as far as I can remember. And, if I remember correctly, this is why they started the war.

CHAKRABARTI: Professor Jong Eun Lee, what's interesting in that clip, at least, is that Zelenskyy isn't saying, "And we need to recapture all of our lost territory as well."

What do you hear in what Zelenskyy said there and lessons, if any, that you would draw from the Korean conflict?

LEE: What I find, one thing to note is that Zelenskyy's clip was during the early part of the war, for the Ukraine war, last year when the Russian army was still occupying a larger portion of Ukraine's territory.

Now, that Ukraine is leading the county offensive and they have liberated more portion of their territories, Ukraine's position has become much more maximalist. In which Ukraine, far from declaring itself to be a neutral nation, Ukraine wants to join European Union, Ukraine wants NATO membership, and Ukraine wants to liberate all of Ukraine, including Crimea.

So there has been a change of Ukraine's position. However, yes, one difference I would notice that for the South Korean government, even before the start of the Korean War, South Korean government has declared all of Korean peninsula as part of South Korea's right for sovereignty. So since then, South Korea's position has been maximalist.

Now, they knew they could not actually start the war. But with the Korean War, South Korean government actually saw an opportunity that, with this war, maybe they could use U. S. force, with their help, to retake back all that's justifiably Koreas.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so before we talk about, allow our imaginations to consider what might be possible actual ways forward here. Professor Malkasian, I want to ask you a question about political realities in these two different eras, because if memory serves, we've talked about Syngman Rhee, leader of South Korea during the Korean War, he wasn't necessarily a democratically elected leader. But he was essentially a de facto dictator who did not have to worry about whether or not the South Korean people were on board with whatever armistice agreement ended up being signed.

Whereas Zelenskyy, as we're talking about, is an elected leader in Ukraine, and certainly the will of the people of Ukraine is going to strongly inform any agreement if ever entered by the Ukrainian government.

MALKASIAN: That could probably go either way. The Ukrainian people may also want to see some degree of peace, and some degree of an end to the violence.

And that may provide pressure on Zelenskyy that Syngman Rhee didn't face. Although Syngman Rhee had a good deal of South Korean supporters who also thought the whole country should be unified. So there's a bit of ambiguity there. But I think that factor may actually, could possibly help toward negotiations.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so why should we look at the Korean armistice agreement as one potential model for what could happen in Ukraine, Professor Malkasian, go ahead.

MALKASIAN: So it comes into some of the things that you started talking about, which is A) there's a stalemate going on. And it's difficult to see how the stalemate is going to resolve itself quickly.

B) The political issues are quite thorny. And having an armistice type agreement, where all we're doing is settling where the fighting's going to stop, along a certain line, there'll be ceasefire, there'll be supervisory arrangements for that, some degree of international participation to understand what the terms of that supervision is.

That can provide a way for the violence to at least stop. That reduces the chances of war breaking out to a larger extent. And, frankly, reduces some of the chances of nuclear war that we're all somewhat concerned about.

CHAKRABARTI: Can I just jump in here for a second? Because what you said is an important distinction.

If I'm reading it right, an armistice doesn't necessarily give either side the ability to declare victory or defeat, right? Versus a complete abdication or other kinds of ends to war.

MALKASIAN: Yeah, I think that's a benefit to it. Now, of course, Putin is going to declare all kinds of things, in any kind of results of this, any kind of outcome to this conflict.

But what an armistice does not do is establish a official political settlement. It doesn't say where those occupied territories actually belong. It doesn't figure out what the future relationship of Russia and the Ukraine should be. It leaves all that stuff static in order just to enable an end to violence.

So that has some benefits.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. Of course, it's impossible to read the minds of all the Ukrainian people in terms of what they would want. But on that point, Professor Jong Eun Lee, 70 years later, how do the people of South Korea see the armistice today?

LEE: That's a great question. So there is a difference between South Korean government's official position and probably the mood of the South Korean public at large.

Even though 70 years have passed, South Korean government still constitutionally recognized itself as the only legitimate government over the Korean peninsula. And the Korean constitution recognized, declared all of Korean peninsula as part of Korea's territory. And reunification is still South Korea's government's official position.

So we even have a ministry of reunification. The formal position has not changed. However, for the Korean public, if you look at polls, especially among the younger generations, there seems to be a significant shift of attitudes in which South Korean public seem to have accepted the de facto division of two countries.

Which itself is controversial for me to say it. Two countries, North Korea and South Korea, that we have been divided this long enough, there's a distinct cultural, political, economic differences. So perhaps, rather than trying to start a war, or even trying to unify in a very expensive way, like the West and East Germany did, perhaps more of a gradual, peaceful coexistence and partnership could be a much more realistic way.

That seems to be a much more accepted norms among, especially among younger Koreans.

CHAKRABARTI: That is such an important observation, right? Because essentially what you're saying is 70 years ago, I don't, I think hardly anyone would imagine that South Korea would become the country that it is today.

LEE: No, no.

CHAKRABARTI: On all those vectors.

So we've got about a minute left.

LEE: May I just add one thing? Sure. Yes. In fact, that was actually the argument that Dulles, President Eisenhower, Secretary of State Dulles, tried to convince South Korean government why you should accept armistice. That if you accept the armistice, U.S. will provide you the necessary economic aid to rebuild your economy.

So even without starting war again, South Korea, with a growing economy, you will have the economic and diplomatic leverage to negotiate better and peaceful solutions to reunification.

CHAKRABARTI: I see.

LEE: Syngman Rhee was not convinced, but that's what Dulles try to make a case.

CHAKRABARTI: I see. So not just a defense pact, but also significant investment.

Very interesting. Yes. Professor Malkasian, we have 30 seconds left. I'm just going to give you the last word here today. Go ahead.

MALKASIAN: So thank you for having me on here. It's been great talking with you and Professor Lee. And I think what I hope most of all is that we're able to look back on the Korean war.

And realize that there's some valuable lessons to be taken from it, that it's a conflict that continues to be worth studying, and whether or not an armistice can work in Ukraine. It is the Korean War, certainly gives us some examples to ponder and think about.

This program aired on September 8, 2023.