Advertisement

Pharmacy benefit managers: The middlemen who decide what you pay for medications

Resume

Americans pay too much for prescription drugs. Big Pharma has gotten most of the blame. But there's a middleman between you and the pharmaceutical companies.

That 'middleman' is a set of companies making huge profits from drug prices. They’re called pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs.

"It's remarkable the number of ways in which the PBMs are using this market to make money for themselves in ways that are not transparent to you or your employer or the American public," Kevin Schulman, a professor of medicine at Stanford, says.

Today, On Point: The middlemen who decide what you pay for medications.

Guest

Erin Trish, co-director of the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy Economics.

Also Featured

David Balto, former attorney advisor to the chairman of the FTC.

Marion Mass, urgent care pediatrician in Philadelphia and co-founder of Practicing Physicians of America.

Related Reading

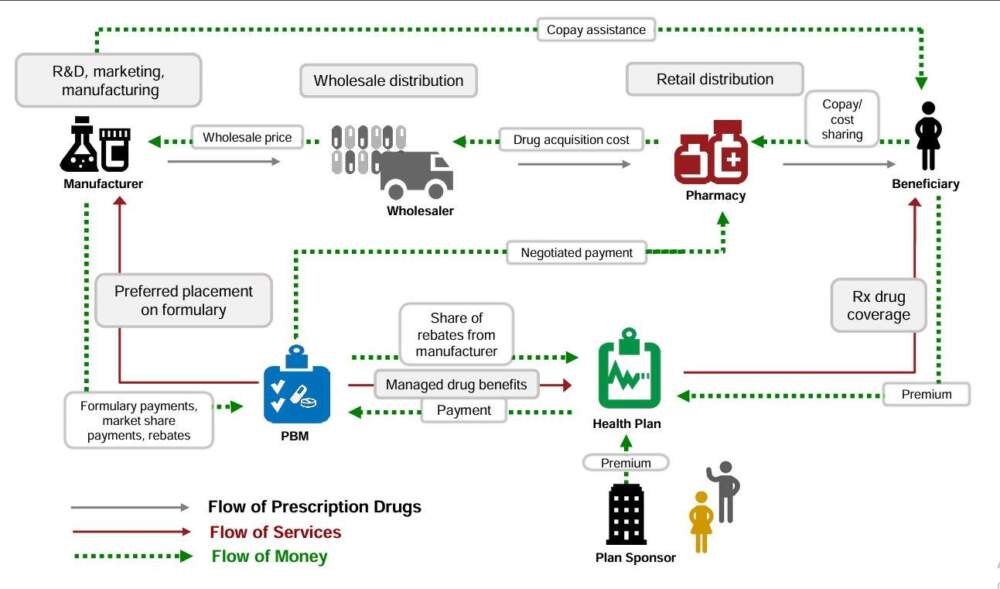

USC Schaeffer: "Flow of Money Through the Pharmaceutical Distribution System" — "US spending on prescription drugs has been growing rapidly, prompting calls for government intervention to slow the upward trend."

Transcript

Part I

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: Given the news, earlier this month might have as well been last century since there's so much happening in the world and it's hard to remember or keep track of what's going on. So let's dust off our memories and pull up a clip from a show we did on December 4th. It was about the staffing crisis at America's pharmacies.

Sara Sirota, a policy analyst at the American Economic Liberties Project, told us why that crisis is happening, including this reason.

SARA SIROTA: And then on the other end is the way that they get reimbursed through entities called pharmacy benefit managers that represent the insurance industry. And they too are represented by three major companies.

Express Scripts, Caremark, and OptumRx, and they, too, hold monopoly power and are systemically under reimbursing pharmacies, potentially even below their costs.

CHAKRABARTI: So let me ask you one quick thing. So just to be clear, because the world of pharmacy services, anything related to American health care is extremely confusing. I'm a visual learner, so I want to be sure I understood what you said.

So that we've been seeing sort of a consolidation in the end point pharmacies, right? The corporate pharmacies, because as you said, they're driving the smaller independent ones out of business. Then regarding the pharmacy benefit managers, did I hear you right when you said there's only three companies there?

There's three companies that pretty much own about 80% of the market.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, pausing there because as I listen back to that cut. It was still confusing. Now even though that hour was about end point pharmacies, the places where you actually go to pick up or get your prescription drugs, these things called pharmacy benefit managers kept coming up over and over again in that hour.

So let's jump back into the show. This is a little bit later and you're going to hear from Shane Jerominski, practicing pharmacist.

SHANE JEROMINSKI: It's very difficult to have an independent pharmacy. And that's the reason why I would say if we don't have wide scale PBM reform, 10 years from now, there'll be very little independent pharmacies left.

CHAKRABARTI: Pharmacy benefit managers are one of the sort of less understood parts of the American health care system that I haven't gotten my head fully around yet, so I'm thinking we need to do some explainer shows about that.

CHAKRABARTI: I'm Meghna Chakrabarti, and at On Point, we like to think of ourselves as a promise made, promise kept outfit.

So today, what are pharmacy benefit managers, and why do they have such a huge influence on your prescription drug prices? And by the way, today's show doesn't just come out of the blue. CVS Caremark, one of those PBMs, recently announced some major changes to their service in order to get ahead of increasing scrutiny on PBM Practices.

We'll talk about that more in a couple of minutes. But joining us today to disentangle this web of pharma prices is Erin Trish. She's co-director of the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics. Erin Trish, welcome to On Point.

ERIN TRISH: Thank you for having me.

CHAKRABARTI: I'm going to rely on you a lot to help us disentangle this web.

So as I said earlier in that clip from December 4th, I am a very visual learner. And I'm actually looking at a chart that you wrote here about how, what the relationships are like between the different organizations that lead to you picking up a prescription drug at a pharmacy. So can we pretend like we've got a big whiteboard in front of us?

Right now, Erin? You and I.

TRISH: Yes indeed.

CHAKRABARTI: And let's help me trace the path of how a drug comes from, let's start all the way back from the development in a pharmaceutical company and then its manufacturer. Where does it go then?

TRISH: So if we're talking about one, one reason why this is complex is that there are different sets of boxes and arrows that talk about the physical product, the physical flow of the product itself versus the financial flow.

CHAKRABARTI: So we're considering, we're all about the financial flow today, right? Given what PBMs are.

TRISH: Indeed, yes. PBMs sit in the middle of the financial flow of it.

CHAKRABARTI: Alright, so let's follow the money. What happens, what's the first place that we should think about?

TRISH: So you're right that the kind of physical drug is manufactured by a drug manufacturer, goes through a wholesalers and distributors to land at the pharmacy where the patient picks it up.

And so in that sense, that's a market like any other good. What gets complicated is when you think about how do we determine the price of that? And the way that the dollars flow, and follow the money, as you say, and that's where it starts to get extra complex and excessively complex in some ways.

So PBMs sit in the sort of center of several different pricing transactions. One that you and your previous guests referred to is that they're the ones deciding how much a pharmacy is actually going to get paid for dispensing that drug to a patient, when the patient picks it up. But there's two other key kind of pricing negotiations or decisions that they're involved in.

One of the others is that they're also contracting with health insurers or employers or Medicare Part D plans to determine how much they're going to charge the end insurer when that patient picks it up. So there's nothing that actually guarantees that how much they're charging the insurer is the same as how much they're paying the pharmacy.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So Erin, if I may, I am just really very determined to understand this well enough by the end of the year that I could write a paper on it, not like a university paper, but at least a high school level paper. So you'll have to forgive me if I keep going over some questions just to be sure that we're rock solid on them.

TRISH: Of course.

CHAKRABARTI: So in the somewhat linear flow of money here, I'm actually looking at the chart that you made, okay back in last year, last summer. And it says there's a green line that goes from manufacturer to PBMs to pharmacy benefit managers. And in that green line that says formulary payments, market share payments, and rebates.

What is that?

TRISH: So this is the third kind of arm of the financial negotiation that PBMs are doing. And this is with the drug manufacturers themselves. So you may have heard of something called a list price of a drug, or essentially the price that is set by the drug manufacturers. So in particular, this is for manufacturers of branded drugs.

When they're selling their product into the market, they're selling it at a list price. And so when you go to the pharmacy, that's the kind of price that you would see if you look at the receipt. But what PBMs are doing is they're going to that manufacturer and saying, "Look, I want a discount.

I'm here to negotiate a discount off of that list price with you." And in exchange for that, I'm going to construct something called a formulary, which is a list of drugs that are covered by this PBM. And I, the PBM, have the ability to puts your drug on a preferred tier where the patients will pay be encouraged to use your drug over a competing product.

And in exchange for that, I want a bigger discount, or what's called a rebate, and it's paid after the fact. And so this is one of the reasons why it's so complicated to talk about drug prices in the U.S. Because there's these list prices that you see on the receipt, but then the net dollars that the manufacturer is receiving, or the net price from the drug manufacturer's perspective, is something quite different.

Because there's all of these other after the fact rebates and discounts.

CHAKRABARTI: Is it lower or higher?

TRISH: So the net price is generally lower than the list price, right? On average, rebates vary quite widely across different types of drugs. But if you look at, for example, the Medicare Part D program, which is the program that provides prescription drug coverage for the elderly, about 50 million Americans, there, the average rebate off of the list price is about 30%.

So PBMs are negotiating on average about 30% discounts off those drugs. But like I said, there's some drug classes where that's upwards of a 70% or 80% discount off the list price, or a huge wedge between the list and the net price of the drug.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so let's introduce a fictional drug here, and add some fictional numbers, okay?

Say I am drug manufacturer MeghnaTech. And my list price for drug X we'll call it, Vita Awesome is $100. So I say, hey PBM, pharmacy benefit manager, here's my list price, and they say, we're going to put you on a preferred one, the customer is going to see that $100 list price, but instead what I'm going to give you is $80.

Is that plausible?

TRISH: So essentially it would be, after the fact, you, as the drug manufacturer are going to send a $20 per drug check back to the PBM.

CHAKRABARTI: Oh, okay. Okay. I had that all wrong. Okay. Got it. So I'm sending the PBM MeghnaTech is sending 20 to the pharmacy benefit manager. Okay.

Okay. Got it. Now looking at your chart. This is going to take up the whole hour, but I swear I'm determined to understand this. There's a line that goes from the PBM, there's several, but the PBM to the pharmacy itself, so your neighborhood pharmacy, and there it says negotiated payment. What is that?

So this is the PBM is determining when that patient goes and picks up the drug that you manufactured at the pharmacy in their community or through some other pharmacy. The PBM is also negotiating or setting a contract with that pharmacy about how much they're going to pay the pharmacy when the patient picks up the drug there.

CHAKRABARTI: How much they're going to pay the pharmacy. Okay, so back to Vita Awesome made by MeghnaTech. We have a net price from the manufacturer of $80. And so then the PBM tells the pharmacy, what?

TRISH: So the pharmacy is essentially acquiring the physical drug from typically a wholesale or a distributor and they're acquiring that at a given price.

Now they separately have this contract with the PBM about how much the PBM is going to pay them for that drug. And so the PBM, the amount that it's going to pay the pharmacy, when the patient actually picks up the product there, that's its own kind of transaction or contract in and of itself.

And so the manufacturer, the contract between the PBM and you, the drug manufacturer, is completely separate from the contract between the PBM and the pharmacy. And so those two different prices are not directly tied together.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: Erin, let's pick up where we left off. You talked about how pharmacy benefit managers do this negotiated payment to the pharmacies themselves, who physically have the drug, saying this is how much we're going to reimburse you.

For the sake of our fictional example here, the drug Vita Awesome from MeghnaTech, recalling that the original list price is $100, but that itself could change. Generally, what do PBMs reimburse to pharmacies? Do they reimburse the full cost that the pharmacy paid to get the drug?

TRISH: So that depends and can vary quite a bit.

And one of the reasons why this is so hard to understand, and why it's so complex, is that this isn't necessarily publicly known. There's not a lot of transparency into how PBMs are paying pharmacies. And so it can vary the kind of way that they determine that payment, whether it's a branded drug or a generic drug, But ultimately, that's the result of the contract between the PBM and the pharmacy itself.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. Understood about the lack of transparency. But as you heard from the clips from the other show that we did on December 4th, we had several guests on asserting that, who were pharmacists themselves, that the PBMs were not reimbursing the pharmacies anywhere near what the pharmacies had to pay.

TRISH: So it's certainly the case that there's a lot of, I think, volatility in the way that essentially the prices that PBMs pay to pharmacies are not necessarily aligned with the acquisition costs of those drugs. And that's particularly a problem for any given transaction, pharmacy can have paid more to get the drug than they're ultimately reimbursed for selling or dispensing that drug to a patient.

And I think what we've seen over the last few years is that's become an increasing problem. And just to add to the complexity. Because there's not just this determination of how much the PBM is going to pay the pharmacy, but there's been a proliferation of these after the fact fees that the PBM is actually clawing back from the pharmacy as well.

So you have the volatility on, those are something called DIR or direct and indirect remuneration fees, or sometimes they're called clawbacks from the pharmacies. And so not only do you have this kind of volatility or a lack of, lack of guarantee that the PBM is going to pay the pharmacy more than what they acquired the drug for, there's also these after the fact kind of fees that they're taking back from the pharmacies.

And that's, I think, part of what's led to a lot of the concern about the viability of pharmacies in this country.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So potentially lower reimbursement rate to pharmacies and fees that the PBMs are charging them as well. Okay. Let's look at the flow of money in the other direction from, let's say, the point of view of the person picking up their medication from the pharmacy.

Obviously, most Americans or a lot of Americans pay a copay right then and there, right? That goes directly to the pharmacy. Does that copay go anywhere else?

TRISH: So that copay typically sits with the pharmacy as part of the reimbursement to the pharmacy.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, but then, of course, there's just the monthly premium that people pay for their prescription drug coverage.

That's obviously going to the health plan itself. Then, how does that health plan, its flow of income relate to any financial exchanges between it and the pharmacy benefit manager?

TRISH: The Pharmacy Benefit Manager is basically the entity that's paying. If we think about how much does the pharmacy needs to get paid or what's the contractually obligated amount that the PBM is going to pay the pharmacy?

When this drug gets dispensed, a portion of that is going to be paid by the beneficiary, and then the remainder will be paid by the PBM. Then separately, the PBM has yet another contract with the health plans that it's servicing to say, "When one of your enrollees goes and picks up this drug, this is how much we're going to charge you."

And essentially, you might be confused and rightfully so, about why are we talking about these two different things, but there's no guarantee that the amount that the PBM is paying the pharmacy is actually the same amount that it's charging the health plan for the existence of that transaction or basically for that pharmacy fill.

CHAKRABARTI: Erin, my eye's twitching a little bit because I fear that I'm failing in my goal to completely make it clear what PBMs do. We did the best that we could. A little later, I'm going to ask our producers, the chart that you made is excellent. I'm going to ask them to put it on our website.

... So thank you for trying to guide us through. Let's see if we can summarize what we just learned. Pharmacy benefit managers, they are essentially a middleman that's organizing the rebates that we talked about, from manufacturers, costs that pharmacies, not that they pay for the drugs, but the amount they'll get reimbursed, including the fees a PBM might charge.

And then also there's the interesting relationship between PBMs and health plans. So would you have a way to summarize the role of pharmacy benefit managers in this really complex system?

TRISH: I think the sort of best way to think about it is that the PBM sits in the middle of the financial flows for prescription drugs in the U.S.

There's more touch points than I think you might appreciate if you didn't have this Set of boxes and arrows and realize just how complex this is, but they're essentially doing three major functions in terms of those financial negotiations. 1, is they're negotiating or determining what the drug manufacturer, what are any rebates or after the fact discounts that the manufacturer is going to give back to the PBM.

So they're essentially negotiating discounts off the list price of the drug with the manufacturer. That's part one. Part two is that they're determining how much the pharmacy is going to be paid when a patient comes and picks up that drug at the pharmacy. And then point three is that they're negotiating with employers or health plans about how much those employers or health plans are going to pay.

When their enrollee goes and picks up that drug, and part of that negotiation as well is to what extent are they going to share some of those rebates that they negotiated with the manufacturer back with the employer, or the end health plan or any other types of negotiations with that health plan, as well.

CHAKRABARTI: I'm just grimacing here. On this end of the radio, Erin, because I consider myself a semi confident person that usually is able to understand systems pretty well, but this one still just keeps stumping me a little bit. So let me ask you this. We've been hearing more about PBMs or even just like their existence over the past couple of years and not prior to that, have they always been around and just not really known by the public or are they a new part of the financial flows in the pharmaceutical system in this country?

So they've actually been around for quite a while and started back in the '70s and '80s really to gain traction. I think their role back then was really to start thinking about the organization of pharmacy benefits.

But importantly, and they played a very important and impressive role in helping transition patients quickly to generic drugs, when those generic drugs became available. And that was their historical role.

I think one of the reasons that we've heard about them more and more over the last few years or the last decade or so, is that they've played an increasingly prominent role in the U.S. health care system and particularly in the pharmaceutical system. So I think part of this is they've gotten bigger. We have 3 representing about 80% of the fills or the kind of prescription drug claims in the U.S. today.

They've also gotten vertically integrated, so they're now often owned by an insurance company, they typically own pharmacies as well. And so their kind of presence as entities has expanded in the U.S. health care system. But I think there's also an increasing attention being paid finally to the role that they play in ultimately the drug prices, particularly that patients face at the pharmacy counter.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, we're going to get to that, because that's really the thing that people care about. But the three companies that you said that control 80% of the market here CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and the third one's --

TRISH: OptumRx, which is part of United, yes.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, I should know that one because that's my plan. So we reached out to the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the national association that represents pharmacy benefit managers. They sent us back a statement which read, in part, pharmacy benefit companies welcome and support competition in the marketplace.

The PBM market is extremely competitive, and employers and health plans have the flexibility to choose the pharmacy benefit design that works best for their business. Today there are 73 full-service pharmacy benefit companies operating in the U.S., and the number of PBMs competing for clients increased 10% in the last two years alone.

So yes, there may be 73 full service PBMs, but they have a whopping, basically, 70 of them have to split 20% of the market between them.

TRISH: That's correct, and I think even, often those numbers are thought to be even a little, the 80% is thought to be even a little under exaggerated in some sense, because some of many of the smaller PBMs, will what's called rent the contracts or kind of have separate side contracts with the big PBMs to get the benefits of some of their either pharmacy networks or other kind of rebate agreements.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, we're going to take a quick pause here because I've got to say, I'm Meghna Chakrabarti. This is On Point. Okay, Erin. We've got, we've gotten to the place now. And thank you so much for holding my hand through all this. Like I said, just we, at this show, we really feel it's important to talk about stuff that like barely anybody understands, but has a really outsized impact on our lives.

And I can't think of anything bigger than how the hidden players that are determining how much we pay for our highly priced prescription drugs in this country.

So if you stick with me for another minute, we really wanted to dig into how the PBMs mushroomed into these huge, complicated conglomerates. As you mentioned, only three of them control 80% to 85% of the market. Here's a little history lesson. You're going to meet David Balto. He advocates for more competition and transparency in prescription drugs, and runs a website called pbmwatch.com.

DAVID BALTO: I used to be the attorney advisor to the chairman of the Federal Trade Commission and the policy director of the FTC. And I've spent decades trying to police the anti-competitive conduct of PBMs. We looked at 2 efforts by pharmaceutical manufacturers to buy PBMs, and we saw an inherent conflict of interest that the PBMs would be able to favor those companies' own drugs.

So we put a stop to those deals as they were structured.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, the mergers he's referring to were Merck acquiring Medco, and Lilly acquiring PCS Health Systems. But in 2011, when two of the largest PBMs, Express Scripts and Medco, wanted to merge into an even larger company, The Federal Trade Commission did not stop it.

BALTO: Over 70 congressmen wrote to the FTC and said, "Please just say no." But the FTC approved the merger and people were very puzzled by that. And what really happened was the FTC and the Obama administration had fundamentally made a Faustian bargain with the PBMs. The PBMs had come to the administration and said, "You want the largest entity possible to negotiate with drug companies to restrain drug prices."

So Obamacare could really succeed, and Obamacare was in its infancy then and the administration, the FTC bought into that argument and like any Faustian bargain, it was a bad deal.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, to make what he's saying clear, if Congress was not going to allow the government to really flex its negotiating power as the largest purchaser of prescription drugs in this country, PBMs argued you need a giant private sector organization or company to do that instead.

Now, Balto really chafes at some of the things PBMs are doing now to reap bigger profits. For example --

BALTO: For decades, PBMs prevented pharmacists from telling consumers that there was a lower cost way of getting their drug. Oftentimes, drugs are cheaper when you don't use your PBM card, you don't go through the PBM, but you just buy it with cash.

But if a pharmacist told you that, the pharmacist would be terminated from the network and lose all their customers. So fundamentally, pharmacists were gagged from telling consumers what choices they had. Now, eventually, during the Trump administration, Congress passed legislation to prevent those gag clauses, but it's a sign that PBMs make money by hiding information and deceiving consumers.

CHAKRABARTI: Now recall, David Balto is a former member of the Federal Trade Commission, and he says agencies like the FTC and FDA have not protected the American's consumer, or patient, as those agencies are supposed to.

BALTO: If the enforcement agencies were graded on how they've used the antitrust laws to protect consumers against and anti-competitive conduct of PBMs, they would get a failing grade. They permitted tremendous consolidation among PBMs and have taken no enforcement actions to stop egregious anti-competitive conduct by PBMs.

CHAKRABARTI: That was David Balto, former attorney advisor to the chairman of the Federal Trade Commission. He's now a lawyer and advocates for more competitive drug pricing markets.

Erin Trish, tell me what your response is to what David said. Are we at a point where PBMs are behaving like virtual monopolies?

TRISH: So I think there's a lot to unpack in those comments. I think it's certainly the case, right, that the view back in the time of the Express Scripts, Medco merger.

And if you think about who at the FTC was really reviewing this, it's sat in the part of the agency that's really focused on the pharmaceutical industry. And from their view, I think they saw it as, we need some entity to negotiate with drug manufacturers over the price of drugs, right? We do this for hospital and physician services as well, right?

We have insurers who negotiate networks of physicians or hospitals in exchange for those hospitals or physicians accepting discounts or lower prices rather than their version of list prices. And so the concern, though, is that it's unclear that, it's certainly clear that PBMs have effectively negotiated lower net prices with drug manufacturers.

What's less clear is whether they've actually passed on those savings to really benefit consumers and patients at the pharmacy counter.

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: Now, we reached out to the biggest PBMs in this country, and we heard back from CVS Caremark. We heard back from Phil Blando, who's the Executive Director for Corporate Communications at CVS Caremark. And in a statement he sent us, he said, quote, he said the following quote, "We're making health care more affordable and accessible for the millions of people we serve every day.

We work to negotiate the lowest net cost for drugs, identify safe and clinically effective products for patients and support the unique needs of our customers, driving better health outcomes and lower out of pockets costs for consumers." He goes on to say, "If PBMs did not exist, they'd have to be invented, because we are the only part of the supply chain that drives drug costs down, going head-to-head with manufacturers to negotiate the lowest net cost for our customers.

No industry does more to make the use of prescription drugs safer and more affordable." So that's from CVS Caremark. A different view comes from Kevin Schulman, who's a doctor and health care economist at Stanford. And he said because of PBMs, the cost of a vial of insulin, I should say, is vastly different on either side of the U.S. Canada border.

KEVIN SCHULMAN: At one point, about two years ago, insulin cost about $270 some odd dollars in the United States. And about $32 in Canada for the same vial of insulin. Detroit's right across the bridge from Windsor, Ontario. One side it's $278, the other side it's mid thirties.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so Erin, how would you describe or analyze the impact that PBMs have on that final payment that people are making when they need their medications?

TRISH: So essentially, PBMs are you can think of them as the firefighters of drug prices, but they're also the arsonists, right? They have every incentive to push the list price of drugs up. Because typically their compensation is tied to some portion of either the discount or the rebate that they negotiate, or some other type of fee.

That's tied back to the list price of the drug. And yes, it's true. They're negotiating lower net prices, but they're also playing this important kind of part in pushing the list price of the drug up. So you talked about insulin. Let's take a specific example there.

My colleagues at the Schaefer Center in a study led by Karen Van Nuys and colleagues looked very specifically at the insulin market from 2014 to 2018. What they found in that study was that the list prices of insulin increased quite a bit over that time period. But the net prices or the revenue that manufacturers actually received was falling over that time period. And what was happening was that more of, we were basically spending about the same amount of money.

But more of those dollars were going to PBMs and other intermediaries in the supply chain. To the extent where more than half of the spending on insulin in 2018 was going to these intermediaries rather than the drug manufacturers themselves, the share of spending captured by PBMS increased by about 155% over that 5 year period.

And ultimately what that means is that more and more of the dollars that we're spending on these drugs, like in this example, insulin, are going to PBMs rather than to the drug manufacturers.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. And then we also have, sorry, I'm just pausing because 155% is a really large number. But then we also have, as you mentioned earlier, and just want to talk about this for another quick second, that vertical integration, right?

I've mentioned CVS Caremark, obviously there's the CVS portion of it, their actual pharmacies, and the Caremark portion, the PBM. That's one form of vertical integration. The PBMs themselves also offer mail order pharmaceuticals, and did I also hear you say there's some integration between health plans and PBMs themselves?

TRISH: Yes, so Cigna is integrated. Cigna, the health insurer is integrated with Express Scripts and likewise Aetna is integrated with CVS Caremark.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. Wow. That's another show in and of itself, although I may not, I don't know if I'll actually get to it. This is so helpful, Erin, because again, just in the past couple of years, there's been more expression of public or public expression of disgruntlement over the impact PBMs are having on the financial flows in pharma in this country.

So much that the pharmaceutical trade group, the major pharmaceutical trade group in this country, Pharma. Now these are the Merck's and the Eli Lilly's of the world. This is their representative group in Washington called Pharma. They are actually running ads right now that are really maligning PBMs themselves.

For example, here's an ad in which, this is a television ad, where a guy in a suit from a patient's pharmacy benefit manager walks up to a woman who's standing at the pharmaceutical sorry, at the pharmacy counter. Okay, so she's there. Guy in a suit walks up, and he takes her to another pharmacy. And here's why in the ad he says he's doing that.

ADVERTISEMENT: Did you know there's a middleman making decisions about your medicines? That's me, your pharmacy benefit manager. Let me take you to a pharmacy where I make more money on that. Come on.

CHAKRABARTI: Erin, what does it mean to you that the pharmaceutical companies themselves are now saying, "Hey, there's a problem here with PBMs?"

TRISH: I think a big part of this is that pharmaceutical manufacturers have taken a lot of the kind of policy attention over the last decade or so about drug prices. And I think it's clear to those of us who have studied the industry, that play a very important part in drug prices, and they had largely been left out of the policy discussion for quite some time.

Now, that's changed recently. But I think if you think about what do patients care about, right? They care about what they're spending on drugs and the dollars that they're facing, the cost that they face when they pick up that drug at the pharmacy counter. And PBMs are, have played a pretty important role in, as I said, the incentives to increase the list prices of drugs.

And there's a particular issue that oftentimes beneficiary cost sharing, if they're in their deductible or if they pay a co-insurance, that's a percent of the list price of the drug. Or if they don't have insurance, right? The price they're paying is tied to that list price rather than the net price of the drug.

So the PBM may be effectively negotiating some discount, but ultimately the patient is paying more because their price that they pay out of pocket is tied to that inflated list price. This is particularly problematic because it creates this issue where sicker patients are the ones who they're taking these highly rebated products, but they're paying much more at the out of pocket at the pharmacy counter.

And essentially, you have this world where these sicker patients are paying more to subsidize the premiums for the healthier beneficiaries. And that's the opposite of how we think insurance is supposed to work.

And so I think getting back to your question about pharmaceutical manufacturers, as they've been taking the hit for drug pricing and the consternation that, rightfully so, patients experience or express from the drug prices, that they're from the out-of-pocket prices that they pay when they go pick up that drug. It's really the PBMs that are an important part of this conversation and had been left out of it. In the kind of discussion of drug pricing policy reforms for quite some time.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. But I think they know that they're no longer going to be left out of that conversation, because in a few minutes we'll talk about some changes that CVS says it's making and also maybe some activity in Congress.

But there still is this lingering question of not only just cost, but is it having an impact on the care upstream at the doctor's office that people are even receiving? Dr. Marion Mass thinks yes. She's an urgent care pediatrician in Philadelphia and co-founder of Practicing Physicians of America.

MARION MASS: You, the patient in America, have thought probably all along that it was your doctor who was making the decisions as to what medication that you get.

CHAKRABARTI: She says there are two ways that pharmacy benefit managers constrain doctors who manage your health. One is called, quote, non-medical switching.

MASS: This is a scenario in which a patient is rolling along and maybe they're stable on a drug.

So imagine you're a patient with a seizure disorder. You have epilepsy. You've achieved stability on drug X. And then along comes the PBM and says, "Nope, I'm going to switch you." It's a non-medical switch because they didn't do it for medical reasons. They switch a patient to a drug that maybe it's not going to control the patient's seizures.

Now you put yourself in the shoes of that patient. Wow, it's a lot of stress if you have a seizure disorder. You've got to be afraid when you're driving or operating any kind of machinery or if you're taking care of your child. You have a seizure, you might hurt yourself, but you could hurt someone else.

CHAKRABARTI: Dr. Mass says that in one Florida study, they found that 67% of patients who were non-medically switched from a drug that was working eventually complained of worse side effects on the new drug.

When that happens, many patients just stop taking those new drugs, which, of course, worries themselves, their families, and their doctors.

Another way PBMs affect the care you get, according to Dr. Mass, is called formulary exclusion, which means medicines doctors want to give their patients off their list, or these are medical medications, excuse me, that are off the list. The formularies.

MASS: So in 2016, you took those three PBMs.

There were only two oncology medications excluded. But in 2022 there was almost 100. These three companies controlling 80% of America's prescription drug benefits, they went from excluding two cancer drugs to excluding almost 100 and some of these are drugs for which there is only one formulation.

In other words, there's a brand name and there's nothing else.

CHAKRABARTI: For Dr. Mass, medicine practiced in America today is done so by two kinds of people. This is what she says. She calls them the scrubs and the suits.

MASS: A scrub is someone who trains for years, whether as a physician or a nurse or they're the ones that are actually seeing the patient day to day.

And you as a scrub are the ones that actually see the patient, but it's the suits that are making the decision without any medical training. Functionally, they're practicing medicine without a license as far as I'm concerned.

CHAKRABARTI: So finally, how does medicine by PBM or the suits as Dr. Mass calls them, how does it affect doctors themselves?

MASS: It's really embarrassing to have gone through your four years of college, your four years of medical school, your three years of training, and then maybe an additional four to five, and then you have to be the one to look your patient in the eye and say, "I'm sorry, I, the scrub with all this training, can't fix the problem for you."

It's downright embarrassing.

CHAKRABARTI: That was Dr. Marion Mass, an urgent care pediatrician in Philadelphia and co-founder of Practicing Physicians of America. And by the way, I just have to say that CVS Caremark, again, in the statement they sent us, they insist that they are making decisions made specifically in order to achieve better health outcomes and lower out of pocket costs for their consumers, and they say, quote, again, I'll read this quote again, "Every day we work to negotiate the lowest net cost for drugs and identify safe and clinically effective products for patients," end quote.

Okay, Erin, so just a couple of minutes left. We got to talk about whether, is this a market that is in need of reform now? In a sense, the pharmacy benefit managers themselves are saying, yeah, maybe they're trying to get ahead of it. Because CVS, of course, just made this big announcement that they're going to make some changes, they say, to how pharmaceuticals are delivered and paid for by patients.

They say they're going to price drugs based on the amount the company actually paid for them, plus a defined markup and additional fee to cover pharmacist costs of handling and dispensing the prescriptions. What do you make of this change by CVS?

TRISH: So I think this is one of those examples where the devil is in the details, and we don't yet know all the details, but at a high level, I think it's indicative of the consternation that people that are participating in this market are feeling, right?

So you do have policy activity going on very actively by the House of Representatives and the Senate and a lot of interest in moving forward with some federal level. Policy initiatives to reform or change the type of behavior in the PBM market, or at least increase transparency and get better information on what's going on.

But you also are seeing private market responses, right? Where you're seeing employers, increasing frustration or patients, increasing frustration and the proliferation of sort of alternative options. We're seeing increasing numbers of patients going to, for example, the Mark Cuban cost plus drug company where they're implementing a true cost-plus formula, chart the prices that they charge for drugs.

You're starting to see, for example, Blue Shield of California announced a pretty significant shake up in their relationship earlier this year. And so I do think some of this is responding to the recognition that employers and health plans have a better handle on that. They're frustrated and that they want something different.

And so this is a response from PBMs to perhaps react or respond to some of those concerns on beat from their clients, essentially. But like I said, we don't fully know what this looks like as it plays out.

This program aired on December 14, 2023.