Advertisement

Is shoplifting getting worse in the U.S.?

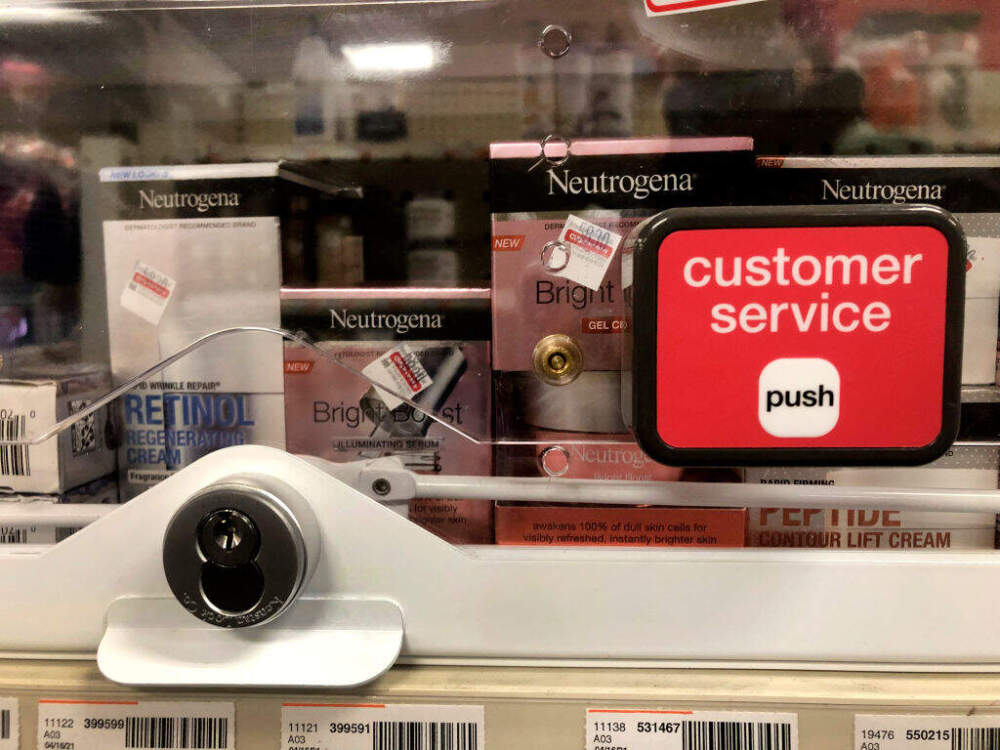

You've seen baby formula and razor blades locked behind plastic cases. Retailers say it's partly because of a rise in shoplifting.

But analysts say there’s no clear data to back up that claim.

"The issue when you drill down into the data is just that it's very difficult to see and to determine whether there's actually been any rise in shoplifting or retail theft," Reuters reporter Katherine Masters says.

Today, On Point: Is shoplifting really getting worse?

Guests

Katherine Masters, Reporter covering retail for Reuters.

Alexis Piquero, Professor of criminology at the University of Miami. Former director of the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Also featured

David Johnston, Vice president of Asset Protection and Retail Operations for the National Retail Federation.

William Scott, Chief of Police for the San Francisco Police Department.

Transcript

Part I

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: You've definitely seen a video like this. It's phone footage of a man wearing a black jacket behind a Walgreens pharmacy checkout counter. And he's stuffing a shopping bag with everything he can pull off the shelves. The staff is helpless to do anything. The best they can do is call the police.

Customers are watching. One man shows his frustration. And then the thief confronts him. He throws bananas and boxes of cold medicine at the customer. And then, the thief throws his bag over his shoulder and walks out the store.

This is On Point. I'm Meghna Chakrabarti. Not only have you seen those videos on social media and on television, you left us messages saying you'd seen that kind of brazen shoplifting with your own eyes.

JULIE: I work with middle school students and high school students and they all have told me that they shoplift regularly and there doesn't seem to be a stigma attached to that. It's on their social media feeds.

Advertisement

JAMES: I currently work for a major retailer and I can say for certain that the shoplifters have become increasingly brazen. They are filling up carts with high-end items. Some of them are even asking us for assistance and having conversations with us. And then they walk out right in front of us. They know that we cannot do anything to apprehend them.

LEGA: I also saw three boys come into Shaw's in Massachusetts and each grab a bag of rotisserie chicken and walk out, very nonchalant. When I have talked to any of the managers about the shoplifting I'm seeing, they don't seem to care very much.

CHAKRABARTI: Those were On Point listeners Lega from Bridgton, Maine; James in Golden, Colorado; and Julie in Bellevue, Washington.

David Johnston, Vice President of Asset Protection and Retail Operations for the National Retail Federation, says he's seeing it, too, across the stores he represents.

DAVID JOHNSTON: I can tell you in my 35, 36 years of doing this, it's unprecedented and unmatched. First and foremost, we're seeing the frequency of theft, the openness and the brazenness of the criminals, the quantities and the type of merchandise that are stolen.

CHAKRABARTI: Johnston says some of the seeming rise in shoplifting may be because of the onset of online marketplaces that make it easier for people to sell goods anonymously. But even as he says that the level of shoplifting we're seeing is unprecedented, he also says this.

JOHNSTON: Well, we don't know exactly what the numbers are. We recognize that, you know, there is a need for adequate and accurate data. And it's challenging both the retailer and the law enforcement side. But even with this challenge of the data presently, it does not change the fact that you can see by going into your local locations, this is a serious and growing issue for retailers.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, anecdotally, there's been no question that there's a change in customers experiences and the visibility of shoplifting now. But add to that the fact that retailers are also fearless in pointing to that seeming rise as the reason why they're closing stores in many, many neighborhoods.

But has there truly been a huge spike in shoplifting? Are stores losing that much money from this one cause, whether it be organized shoplifting or individuals like the banana-hurling shoplifter from that video we played? Well, it turns out there's way more to this story than the viral content that makes it seem like this is a crime wave everywhere, all the time. And that's what we're going to look at today.

Kate Masters joins us. She's a reporter for Reuters and she covers the retail business. Kate, welcome to On Point.

KATE MASTERS: Thanks so much for having me, Meghna.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so this has been going on for some time. I don't think I can spend a day without seeing at least several videos of some pretty open shoplifting here. So let's go back a little bit in time. Because it was the National Retail Federation itself that kind of made a big splash a while ago when it published some information, it said, that pointed at shoplifting as the reason why retailers are closing in some cases hundreds of stores. Take us back to that moment.

MASTERS: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, the National Retail Federation, which is sort of the main lobbying group for retailers all over the country, started flagging this maybe a year or two ago. But the splashiest moment probably came earlier this year when they released a report stating that half of all losses within retail could be linked to what they call organized retail crime, which is a term that you'll hear a lot and essentially refers to theft by anyone for the purpose of reselling those goods rather than personal use.

Now, since then, the NRF has actually retracted that figure and cited erroneous data, which sort of highlights the difficulty of really understanding to what extent shoplifting actually is rising when you drill down into those numbers.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so they retracted that, said it was erroneous data. Did they replace it with any other new, fresher analysis about the impact of shoplifting on retailers?

MASTERS: I think when you look at the retail industry and figures coming from it, usually what is most commonly cited are numbers coming from the National Retail Federation's National Retail Security Survey. It's a mouthful. But that's a survey, a different survey that they conduct every year, essentially asking retailers to assess what type of "shrink: they're seeing. "Shrink" is a term that refers to all losses for any cause. But what we're really looking at are overall shrink rates, which increased slightly from fiscal 21 to fiscal 2022, but are still in line with numbers from 2019 to 2020.

So essentially we're seeing that losses by retailers have mostly been in line with what we've been seeing pre-pandemic. And the percentage of shrink that's attributed to external theft, including organized retail crime, has hovered around 36 to 39% since around 2015. So when you look at the data that's actually coming from the industry and that they're still continuing to cite, it really seems like theft, while it might have risen a little bit, is in line with what we've been seeing since before the pandemic.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so I want to peel back the layers of what you just said a little bit because this whole "Are we having a shoplifting mega crime wave?" thing is based on numbers as we can best understand them. So first of all, "shrink," as you said, is a simple way of defining it as like total losses, like revenue losses that retailers are experiencing or is it defined specifically as something else?

MASTERS: That's a great question. So when we look at shrink rates, it's typically referring to the percentage of inventory losses compared to the overall number or value of sales. And shrink is a number that includes losses for any type. It could be a cashier who rings something up incorrectly at a register. Some retailers calculate supply chain losses within their shrink. So goods that maybe go missing as they're moving along the supply chain.

And I think it's important to really drill down on those numbers because you hear shrink a lot, but when it comes to the issue of retail crime, what we're really looking at is external theft which again is around 36% of all shrink, so all losses.

CHAKRABARTI: Alright. So hold on for a second. So no, no, this is really important, right? Because that's what we strive to do here. We try to get smart reporters on like you to help us really understand what's going on that may be hidden behind those viral videos.

Okay. So let's put some actual numbers here. So shrink is overall inventory loss in comparison to what the value of the sales would have been, right? So let's say, we have a company that says, "Well, we would have had $1,000 of sales based on the inventory that we started with" — How much is shrink on average, all of it, for stores, including the shoplifting or crime?

MASTERS: So when you look at the most recent figures from NRF, we find that shrink rate as a percentage of sales is about 1.6%, based on the data that the NRF has reported. And that's equivalent to about $112.1 billion in total inventory losses for retailers.

CHAKRABARTI: Wow. Okay. So I was gonna say, say we have a company that's got — let's make it an easier number to manage — $100, right, in overall inventory potential sales. This is like a Lilliputian company. It's got $100. And then its shrink rate would be — what'd you say? About 2% overall?

MASTERS: Yep. A little bit under 2%.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So let's call it two. So out of the $100 of total sales they could have had, $2 were lost from overall shrink. And then from that $2 you said that it was what? 36 to 39% could be due to external theft?

MASTERS: You got it.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so let's call it 40, just so I can do that math. So that's $2, .2, times 4 is .8, right? So 80 cents is due to external crime.

MASTERS: Yep, I think you did that math correctly.

CHAKRABARTI: (LAUGHS)

MASTERS: (LAUGHS) And that is about the number that is coming from the retail industry.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. Did I tell you that we do live math here on On Point during the show? (LAUGHS)

MASTERS: I'm very impressed.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So 80 cents out of what should have been a total of, in an ideal world, $100 worth of sales from the inventory they had, roughly. Right?

MASTERS: Roughly.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So, that makes it seem overall that shrink, even in a normal year, due to theft, is very, very small.

MASTERS: It does make it seem like it's very, very small. And here is where I think the issue gets challenging because as retail reporters, we hear retailers flag that shrink is getting worse, that they're seeing more impact on their employees, that there's more concern. But when you really drill down into the numbers, as you mentioned, shrink is a very small percentage of overall retail losses.

Advertisement

There is some data that has come from the Think Tank Council on Criminal Justice, though, that has suggested that the number of shoplifting incidents associated with another crime has risen slightly from 2019 to 2021. So if you compare before the pandemic to mid pandemic. And so I think that's a lot where a lot of the concern is coming from this, this idea that crimes are getting worse.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So there's more to dig into to that in just a moment.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: Just to recap, Kate, the spreadsheet that you took us through, that you started to take us through. Basically the conclusion there — and just check me on this — is that the rate of shrink overall, or the value of inventory losses for retailers hasn't changed all that much and neither has the percentage of losses from shoplifting as very simply defined from pre-pandemic to now. Is that kind of one of the conclusions that we can and should draw?

MASTERS: Yes, I think that's that's right.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. But still, as you hinted, there's nevertheless, a lot of layers beneath that, which we'll get to. But I have to ask, you're in New York, and as listeners know, I'm in Boston. I'm gonna say that, just to be completely transparent, I absolutely have seen shoplifting going on in stores that I visit and frequent.

And I see it a lot. And it's just out in the open. And I don't recall seeing it as out in the open as I have in the past couple of years. I really don't. And I'm just wondering, being in New York, have you seen this with your own eyes or not?

MASTERS: You know, that's a really interesting question. So, I mean, speaking personally and anecdotally, I actually have not seen shoplifting occur in stores while I've been shopping there. But even if you're a shopper who hasn't seen that, I think that the signs and the worry is very visible. You see in more and more retailers, players like CVS, like Ulta, saying that they're installing more cases. They're locking up more inventory. And so that is also a challenge. I think the numbers don't necessarily show what's happening on the ground, but for a lot of shoppers, it does seem like shoplifting is much more visible than it's been in the past.

CHAKRABARTI: Right. And that's something I'd like to try to resolve over the course of this hour. Because I was telling my colleagues here at On Point this morning that I literally just this past weekend went to my local Target. It's one of the mini Targets, an urban Target. And for the first time ever, I would say 60% of their goods are all of a sudden behind these giant new glass — or plastic, I should say — locks.

It was really stunning to walk into the store and see everything, practically everything, except the apples in the back, be locked up. And it makes you feel like there is absolutely a crime wave going on just by seeing those things locked up. So we have to resolve the ample number of anecdotes that Americans have with the actual numbers, as murky as they are.

So, I want to bring Alex Piquero into the conversation. He's a professor of criminology at the University of Miami, and former director of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, and he's with us from Miami. Professor Piquero, welcome.

ALEX PIQUERO: Hi, Meghna, great to be with you.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so, first of all, what's your qualitative judgment of the kinds of data that retailers and law enforcement are providing? Is it adequate? Is it detailed enough? Is it trustworthy? So how can we actually understand the extent of the problem of shoplifting?

PIQUERO: I hate to bring bad news to this conversation, but you can't measure what you can't see and you can't measure what's not reported. And therein lies the problem. The problem is that not all thefts get reported to law enforcement, and not all individuals who are victimized by theft or shoplifting report that to law enforcement. And so there are a bunch of numbers out there, but the numbers are lacking because it doesn't have the sufficient detail that we need as criminologists, as media personnel, as well as, you know, when we take our work hats off and we're just regular public people. The answer is we don't know what we don't know.

CHAKRABARTI: So, why is it, first of all, let's take those two sides, and let's take the retailer side first. Why is it that they don't have greater clarity in their reporting? I mean, almost certainly, they know more than they're saying.

PIQUERO: Sure. So not every single retailer in America fills out that survey. So there's issue number one. The second thing is not every retailer may report a theft to law enforcement. For example, they might deal with it informally. They might say to an employee or some kid who may have taken a small gift card, "Hey, don't do that again." Deal with it informally. And it never gets coded and it never gets reported. So therein lies the issue, right? If something happens and people don't bring it to the attention of law enforcement, then that event never gets counted.

CHAKRABARTI: Got it. Okay. And then what about on the law enforcement side? Because we have to rely on local law enforcement and state and federal as well, in terms of the different levels, I guess, that data gets added and processed.

PIQUERO: Right. So remember, you have 18,000 law enforcement departments in the United States of America, and they all report data to the FBI. Now, the FBI changed the way they were collecting data from what used to be called a summary reporting system, which is an old system built in the thirties and forties to something called NIBRS, the National Incident Base Reporting System. And that system is going to collect more information as more and more departments start to submit to it.

However, there's no separate retail theft category or separate organized theft category. There's just theft. And so you have to make sure everybody reports and then as well, not every law enforcement will take some kid or some adult who's committed minor theft and actually do anything to that person. They could divert that individual. They may never, you know, arrest that person. Moreover, there could be prosecutors who may not decide to prosecute individuals who commit theft under a certain dollar amount.

So you have all of these headwinds that are coming at the problem of theft that deals with — we've opened up an Excel file and there's rows and columns. They may not all be populated there because of these reasons.

CHAKRABARTI: Mm, okay. In that case, why do you think that major retailers are pointing at shoplifting as not the, but one of the main reasons why some of them are closing a lot of stores in neighborhoods across the country?

PIQUERO: Yeah, so it's a fair point. We're inundated with with what we see on our social media threads that we choose to see. And then we're inundated with this when we watch our local news. And a lot of these acts are brazen and they instill fear among people. And the last thing we want to do is instill fear among people.

And so from the retailers' perspective, they need to control their inventory. They want people to want to work there and they want to have people feel safe at their shopping locales. So from their perspective, I think that they need to be very mindful to not create this panic among people and to bear in mind that is theft increasing? Well, actually, you know, as Kate said, when you compare it to pre-pandemic levels, we're kind of already where we're at in those cities where we can obtain data to answer those questions.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, Kate, let me turn back to you because I just want to read a couple of things regarding Walgreens in particular. We reached out to several retailers. Most of them did not respond to our requests.

But Walgreens' CEO, earlier this year, actually in an earnings call this year said to investors that maybe they "cried too much" when reporting rising shoplifting in 2022. And then in addition, Walgreens did send us a statement saying, "Retail crime continues to be one of the top challenges facing our industry today. We are focused on the safety of our patients, customers and team members and they have programs in place to reduce organized retail theft in our stores."

They continue to focus on this organized retail theft piece, Kate. That leaves out the individuals, and it also leaves out a category that I failed to ask you about earlier which is internal theft by Walgreens' own employees at whatever level. Why do you think they keep focusing on this organized retail theft piece?

MASTERS: That's a really good question. And I think that when you look at retailers overall, even though theft might not be a huge part of their inventory losses, retail in general is a pretty low margin business. Retailers are very, very focused on trying to make profits in an industry where profits are lower than we see in other places. And so that's a top point to keep in mind when we focus on organized retail crime. Because this is sort of what retailers are flagging as what's new about the crime that we're seeing.

When you talk to retailers, they tell us that while the numbers on shoplifting might not report a huge increase, what we're seeing is more and more people who again are stealing, not to use the items personally, but to resell those goods. And going back to what Alex said, the problem with that is that organized retail crime is not a reported theft type and is really only determined through investigation. And so at this point, we're sort of taking retailers' words for it, because there's no concrete data on whether or not we are seeing a big wave of organized groups who are going and stealing items from stores. I mean, it certainly happens, but we just don't have the data to say conclusively whether that's really increased.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so just to be clear — and Professor Piquero, let me go back to you: So is organized retail theft or organized retail crime, Kate just said this more clearly, but it's not a reportable category?

PIQUERO: That's correct. (LAUGHS) I wish --

CHAKRABARTI: So when retailers — Go ahead.

PIQUERO: I wish I could be clear. You know, in the limited data that the FBI releases through the NIBRS system, the majority of shoplifting incidents are actually committed by one or two people. Not three, four, five, six, or seven. Now, what happens, as Kate said, when those individuals get together in some organized theft ring, and if that's busted, that's never a separate category. So if you wanted to know the answers to how many organized thefts rings have been occurring in the United States in the last 20 years, the answer is, "I don't know" because it's not collected.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So then, again, to point to what Kate said, when we're taking retailers' word for it — not only are we taking their word for it, we don't even know what basis by which they're defining organized retail crime or where they're getting their information., other than what they've decided to call organized retail crime. Professor, is that right?

PIQUERO: Yes, that's right. I would agree with Kate completely.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, I think that's an important point to understand here because then when seeing what the statements are coming out of the retailers and the kind of coverage, the kind of media coverage this has been getting, are we are we saying here that like this may be a non-story that's been blown up into a story that's completely seized the eyes and ears of Americans, Professor?

PIQUERO: You know, one of those interesting adages in our world, Meghan — Meghna, sorry — is if you perceive a situation is real, it is real in its consequences. And so we have this issue of perception becomes reality, but we have no data to support either one of those. And so what we want to be very mindful of is we don't want to instill fear and panic among people. And sometimes that's what these videos do. And so this is not an, "Oh my gosh, let's sound all the sirens and put out the Bat Signal." I think this is a sign for, "Okay, let's see what we know. Let's get better data from the retailers." If in fact this is occurring, then the numbers should bear that out.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, so let me just lean a little bit more on your criminology expertise here. The videos exist, not just because the technology to capture the footage exists, but because the brazenness and the openness of a lot of these shoplifting acts or crimes are there. More people are actually seeing them, so they catch it on video.

Now, whether or not that translates to percentage losses changing for the retailers, like you said, I'm not sure that matters. What do you think accounts for — it doesn't matter in terms of our customer experience and our belief and whether or not crime is getting worse in this country — what does it tell you about the openness and the brazen is the word that keeps coming up of the actual acts? Why do you think that's happening?

PIQUERO: I think people like a lot of attention, a lot of likes. (LAUGHS) I don't mean to be crass or comical about it, but I think that's what people are doing. And, you know, a lot of people these days, their world is social media. We're probably old enough to remember when there wasn't that — that didn't exist. And so people had conversations and they had discussions around lunch tables and stuff. But now people live their lives in in this virtual world, and they want everybody to see them and a lot of individuals get a lot of attention in that way. I think that this, this goes back to a more fundamental question is why are these individuals doing this in the first place?

CHAKRABARTI: Yes, exactly.

PIQUERO: And why do they think they can get away with it, basically with impunity? And it goes back to, you know, civility, it goes back to morality and it goes back to telling people, "No, you can't go into a business and steal something that's not yours. Period."

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. Sure. I mean, there are fundamental sort of moral lessons to be drawn here and maybe to return to heavily in this country. But I appreciate you clarifying because really the question I was going for is: Are people doing this more openly because they are fearless regarding any consequence that might befall them, because there are no consequences? Has there just been a genuine drop in policing that's allowing people to walk bravely into stores now, sometimes not even covering their faces and just filling bags with, I don't know, razor blades and shampoo?

PIQUERO: Yeah, sure. I don't think police are walking back or not doing their job. I mean, the men and women who protect this country, you know, lay their lives on the line every single day for us. And so I don't think that that's any reason to think that they are not doing their job. I think what you have is you have some places where certain kinds of thefts are not going to be prosecuted. And so that's a real issue. And so if that's not going to happen, then police should be spending their time on doing other things, keeping people safe in terms of violent crime and dealing with gangs and drug distributions.

But you do have this sense of brazenness. The fact that people have no problem at all smiling into a camera is pretty remarkable. But this is a new world that a lot of us are living in. And a lot of these people are living their lives in these videos and for them, again, the clicks and the likes and everything else is a lot what they feed off of.

CHAKRABARTI: Mm. Well, Kate, let me turn back to you because about not being prosecuted, there have been headlines and stories, like, for example, in New York, where D. A.'s offices are saying they're not going to prosecute shoplifting because they see it as a crime of poverty and not something that should be in the criminal justice system. What do you think?

MASTERS: You know, it's an interesting question. I think that that is why retailers are really focused on the organized aspect of all of this. Because there is a big difference between someone who's going into a store to steal something they need and an organized group that is focused on stealing items and then reselling them. We don't know how much that is happening, but it is happening. And I think that retailers who are worried about their bottom lines are really focused on highlighting that and trying to stop that.

And so in addition to all the sort of external security measures that we're all seeing — the glass cases, maybe security guards posted in stores — you also see this wave of retailers who are really hoping to quantify and figure out which shoplifters are repeat offenders, so they can flag that to law enforcement and have it taken as a crime that's more serious than the crime of need, the shoplifting for personal use that we talked about previously.

CHAKRABARTI: Mm-hmm. Well, just to be clear, though, what I was quoting was a Manhattan D.A. Alvin Bragg, who back in 2021, that's the quote where it came from during his campaign, where he said he grew up with friends disappearing over charges like theft, meaning they were incarcerated. And then he said, "I think we need to move away from prosecuting what I would call a crime of poverty."

But there's like many categories here, right? We keep mentioning organized retail theft. There are some people who might be stealing things because they need them. But then there's also those individual acts that may become organized later when they sell those stolen goods online. Not sure about that, but the lack of data, as Professor Piquero has been telling us, is really at the heart of the problem here.

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: Kate and Alex, I just want to let the voice of law enforcement here a little bit because we spoke with Bill Scott. He's the chief of police for the San Francisco Police Department.

BILL SCOTT: In the last, you know, several years, or at least this year, we've seen a decrease compared to where we were this time last year. And of late, that decrease has been definitely more pronounced and more significant. In the last three months, our overall larceny and theft is down 30%.

CHAKRABARTI: So he's saying overall larceny and theft down 30%. But he also says that the year-to-year date shoplifting numbers were at 2,973 as of December 13 of this year. And that's a drop from 3,618 incidents last year and 3,263 in 2019, meaning pre-pandemic level. So a drop of about 600ish incidents. Nevertheless, Chief Scott says that one component of retail crime does feel like it's growing in his city. And again, here it comes: Organized retail crime.

SCOTT: A lot of this is organized, particularly on the distribution side. But there is a significant organized component to this. So it's like day-to-day toiletries: toothpaste, paper towels. I mean, it's things like that that that are driving a lot of what we're talking about. And we've arrested people on the fencing side of this organization, people who buy stolen property and sell it. For instance, last month we made an arrest and there was $17,000 worth of those types of items.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, we're gonna come back to Chief Scott here in just a minute, but Professor Piquero, again, help us understand what the Chief is saying there. Because while overall incidents, as he said, are going down, he came back to this idea of organized retail crime. So can you just decipher what the chief said?

PIQUERO: Yeah. Getting into his head, I think that, you know, remember police and law enforcement agencies, they have an entire investigatory unit within them. And so when a crime occurs, they're going to dig into the details to see how people might be related to one another. It might could be the idea of called social network analysis. To see what criminals are working together, if they are working together, and then try to bust up those rings. Those kinds of things that may occur after the fact of the original event may never get captured because the only thing that's captured is the shoplifting incident.

And so when you get on the FBI's website and you look at the crime categories, you don't see something that says, organized retail theft. Now, could that be added? Sure. They could add it. And then it would require all 18,000 police departments to then submit those to the nation. And that would be a good thing. And then we'll have a baseline to go forward with to look at these patterns over time.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. So is it possible that when law enforcement refers to organized retail crime, that what they're really talking about is what the chief said there on the fencing side. Like, okay, so maybe individuals are pulling stuff out of stores, but then they're selling it to organizations that then go on and do whatever they do with the products?

PIQUERO: Yeah, that's exactly right. And so it's very similar to what could be for a drug distribution. So one person sells drug to someone else, and then they sell it to a larger mass of people. So that's organized in the sense of there's person A does something to person B or a group C. In that sense, it's organized.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, but in terms of the individuals going into the stores, they may not be formally organized. Alright. So let's go back to San Francisco Police Chief Scott here. He says that while he admits the department lacks specific statistics about shoplifting and the level of organization, they've been able to distinguish organized retail crimes through investigation, which is exactly what you just said, Professor Piquero. But as organized retail crime becomes a growing issue, as the San Francisco Police Department defines it, Chief Scott says he believes new resources will help the department turn the tide.

SCOTT: The San Francisco Police Department just received a $15.3 million organized retail theft grant. So that is going to be really helpful for us to get more equipment to deal with this issue of license plate reader, automated license plate readers, cameras. It pays for some of our personnel costs. It pays for training. It pays for us to have the ability to have collaborative seminars so we can work with other law enforcement agencies around our region and retailers. So we sit down at the table and craft out strategies to work on this together. So that type of support is really, really important. And, you know, we're fortunate to have it here. And we hope that — not hope, I do believe that — that will make a difference in moving us in the right direction.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, Chief Scott says that as the modes of retail crime change, so like how we shop and the kinds of crime that are impacting retailers, the San Francisco Police Department has to change their policing strategies, too. And so far, he's confident that his department will be able to meet the needs.

SCOTT: There are a lot of corporate policies now that are hands off in terms of aggressively arresting shoplifters or people that do these types of crimes. And so what we have learned that I think has been — not I think, it has been — successful is to actually pay attention to that evolution and understand that we have to now work even closer with our retailers.

So the operations that we do here where our officers, with the permission of retailers, are actually in the stores. They're able to observe shoplifting crimes happen, and as soon as people cross that threshold without paying for the merchandise that they have taken out of the store, we're right there to make arrests. And we've been very successful doing that over the last, you know, year, year and a half.

CHAKRABARTI: Kate Masters, have there been other specific policy changes, whether it be in law enforcement departments that you've reported on, or with retailers themselves?

MASTERS: That's a great question. So I think what the chief was alluding to in terms of policy changes is that as we've seen reports of shoplifting and videos of shoplifting get more brazen, a number of retailers have directed not just their regular employees, but even security guards not to confront or intervene in cases of shoplifting. That obviously makes things difficult. I've spoken to employees who say that they feel frustrated because they're not able really to do anything to counteract theft while they're working in stores. Retailers obviously don't want to run the risk of anyone getting hurt.

But at the same time, there has been a lot of movement on the back end to try and address these crimes. At least 34 states have passed laws that either define organized retail crimes and broaden potential penalties or establish task forces between retailers and the police to try to prevent that. And so I think that a lot of those efforts are actually things that shoppers aren't seeing. There's more communication between retailers and law enforcement. There's new technologies that are being implemented, like license plate readers, like incident reporting software that is actually designed to capture incidents and try to connect shoplifters who are hitting up multiple stores in multiple different locations. And so that the things they take can be added together. And will amount to a greater crime, rather than just simple shoplifting, if that makes sense.

The effort is if there is organized retail crime, we want to find who those repeat offenders are and try to make the case to the criminal justice system that these aren't people just dealing for personal use, they're people who are actually stealing large amounts of merchandise.

CHAKRABARTI: If they can gather the evidence to show that. Okay. Point well taken, Kate. Professor Piquero, I'm coming back to the original question that we started this show with and I have to say I'm not quite sure that — maybe we've asked a question that can't be answered, right? Because Kate very clearly laid out like a lot of policy changes, laws in 34 states being changed, we heard from the San Francisco Police Department chief there saying, "Well, yeah, we we got a big investment from the city" in order to improve how they police shoplifting.

So these are actual policy changes and money being spent on a problem that we're simultaneously saying, 'We don't actually have great data to understand if shoplifting is actually worse." Is that a conflict? How can we resolve that?

PIQUERO: It's not necessarily a conflict. Some departments around the United States do collect detailed data on shoplifting.

CHAKRABARTI: Got it.

PIQUERO: So in those departments where they are implementing certain policy changes or whether a mayor or city council or county commission decides to implement some change, then they can do some analyses to compare what was happening prior to the implementation of some policy and then after, recognizing that there might be a lot of other factors also going on at the exact same time that could be affecting crime rates for specific kinds of crimes.

So, I think that's the kind of information that local law enforcement agencies need to start collecting to then assess whether or not this infusion of multi-million dollars and associated strategies with retailers and police departments are actually working.

CHAKRABARTI: Well, we heard from listeners in preparation for this hour because the amount that people have seen, undoubtedly, that's gone up. For example, here's Lauren, who called us from Los Angeles. She owns two stores, one in West Hollywood, another in Manhattan Beach, California. And according to her as a business owner, she says it's obvious there's been an increase in shoplifting.

LAUREN: We have a fine jewelry store in Manhattan Beach that's been hit twice with millions of inventory stolen, smashed and grabbed. Someone drove, the second time, someone drove through their front window in a very organized fashion. Here in Los Angeles, we see grocery stores closing, Walgreens closing, Safeways closing, because they can't sustain the shoplifting losses. So I don't see how anyone could say there hasn't been an increase, but that's just my experience.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, Kate, I just want to take a tiny detour for a minute or two to talk about other reasons why retailers are suffering, according to them, enough losses that does require them to close stores. Because what else is contributing to, let's say a reduction in revenue?

MASTERS: Yeah, that's a really good question. I mean, over the past year, we've really been in an environment where it's not quite a recession, obviously, but we have consumers who are feeling the impact of increased inflation, who are feeling the impact of the Fed's rate hikes. And so in all of 2023, we've heard retailers like Walmart, like Target, like Lululemon, say that they're seeing consumers spending less, being more careful about where they're putting their dollars. And this is obviously a big change from what we were seeing during the pandemic, where shoppers were stuck at home and everyone was buying lots and lots of merchandise.

So in a way, the retail environment is normalizing. But for retailers, they're reporting results to shareholders that aren't as strong as they were two years ago. And now the pandemic also sped up the rate at which people are using e-commerce. And so we also see many more people who are opting to buy things online rather than in stores. And so as a result, retailers with lots of locations are finding that some are less profitable and are shutting those down.

I spoke with one source who works on the NRF's national security survey, and he said that while theft is rarely the primary reason that a retailer will close a store, if a store is high in theft and that store is also not as profitable, then that will contribute to the decision to close down a location.

CHAKRABARTI: I get it. Okay. So it may be the thing that pushes that site over into the one that gets shut down. All right. Now, Professor Piquero, just got a minute or two left, actually less than that. But I wanted to, thinking about, you said there's some law enforcement departments that maybe are tracking things more closely or getting more reliable data sets on shoplifting. SFPD sounds like it might be one of those. But in those cases where things are clearer in terms of, let's say, an uptick, not just in brazenness, but in actual losses due to shoplifting, do you have some, just quickly, some ideas on what policies have been proven to be effective versus ineffective for theft prevention?

PIQUERO: Yeah, the kinds of things that are effective for theft prevention are also the kinds of things that are effective for lots of other crime prevention. And these are multiple prong strategies. It's not just a policing strategy, right? There's also non-policing efforts that have to be combined with policing resources.

But if we're going to focus on policing, we know that several things that police do and they do really well matter. For example, patrolling hot spots or hot corners or hot sections of town. They're focusing their resources in particular places and finding out what the underlying problem is at that location or a group of individuals or some individuals that are frequenting a particular store.

Also, the important point of this is keep them random. So think about when we were back in college, if there's no T.A. in the hundred person classroom, then people might look at their colleague and say, "Hey, what's 44? What's 44? Is it B or C?" But if there's one T.A., two T.A.s, three T.A.s, and they're now randomly moving around, then that creates a threat of detection.

CHAKRABARTI: Ah, okay. Well, Alex Piquero. He's a professor of criminology at the University of Miami and former director of the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Professor Piquero, thank you so much for joining us today.

PIQUERO: Pleasure to be with y'all.

CHAKRABARTI: And Kate Masters, reporter who covers retail for Reuters with us from New York. Kate, it was great to have you. Thank you so much.

MASTERS: Thanks so much for having me.

This program aired on December 18, 2023.