Advertisement

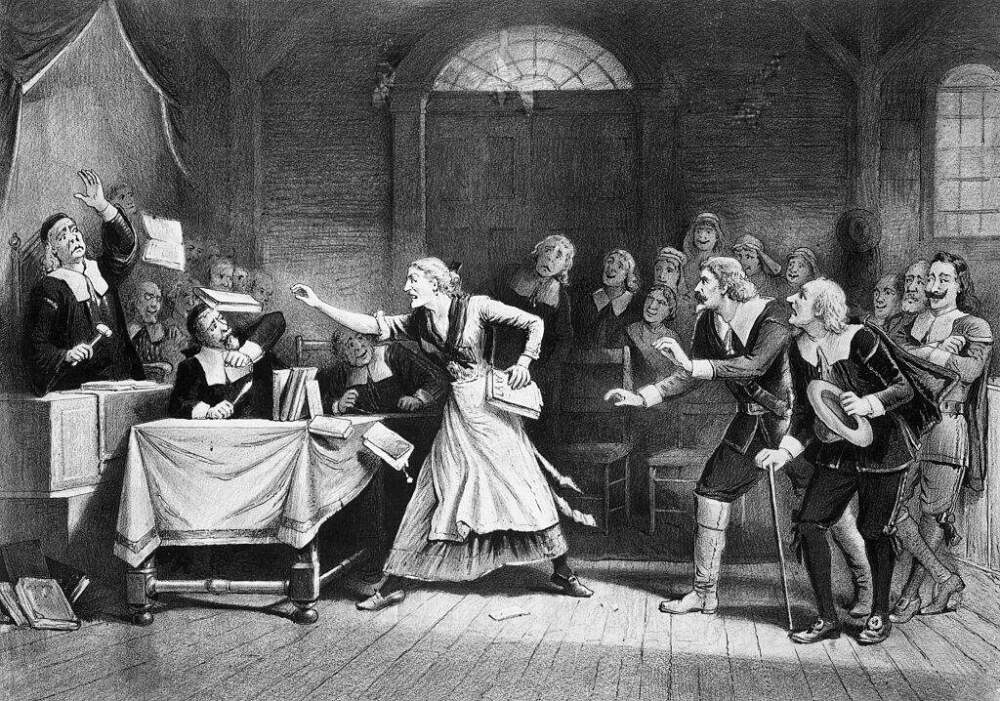

Fear, conspiracy, gender: The long legacy of witch trials

Resume

Secret spells. Magic potions.

The world of witchcraft has a powerful cultural hold and a dark history. What do centuries of witch trials teach us?

Today, On Point: Fear, conspiracy, gender — and the long legacy of witch trials.

Guests

Marion Gibson, professor of renaissance and magical literature at the University of Exeter. She’s written eight books on the subject of witches. Her most recent is “Witchcraft: A History in Thirteen Trials."

Leo Igwe, director of Advocacy for Alleged Witches, an organization that works to defend the rights of alleged witches in African countries.

Also Featured

Shawn Engel, self-described “professional witch.” Offers tarot reading through her business Witchy Wisdoms. Author of several books including “The Power of Hex: Spells, Incantations, Rituals” and “Cosmopolitan’s Love Spells: Rituals and Incantations for Getting the Relationship You Want.”

Transcript

Part I

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: Magic potions, ancient rituals, secret spells. The world of witchcraft has a powerful cultural hold.

OLIVIA GRAVES: Okay so, Frankie and I are doing protection charms for each other.

FRANKIE CASTANEA: I didn’t bring most of my herbal allies because I’m like, I can just raid your kitchen.

GRAVES: Yeah.

CASTANEA: Literally Italian folk magic is like red bag --

CHAKRABARTI: That's YouTuber Olivia Graves, AKA the Witch of Wonderlust. Her YouTube channel has 438,000 subscribers, and on the channel, she teaches how to make a talisman for safe travels and banish bad energy from your apartment. Among other things. You heard her there with Frankie Castanea.

A self-described Italian American folk witch, and here's Shawn Engel, who also describes herself as a professional witch and reads tarot cards among other things.

SHAWN ENGEL: I do live readings for people at large events, large scale events. I also do online readings. I've done a lot within the witchcraft community and provide different spells and services to people that need it.

CHAKRABARTI: We'll hear more from Engel later in the show. She and Olivia Graves are among the growing number of people embracing witchcraft as an empowering practice in their daily lives. It's hard to know exactly how many self-described witches there are, since it's not a tracked religious category, but around 800,000 Americans identified as Wiccan in a 2019 survey from Brandeis University.

But not all witches consider themselves Wiccans. Of course, witchcraft also has a long and often dark history. For centuries, people have been persecuted, tried, convicted, and killed after simply being accused of being witches. And in some parts of the world, like The Gambia, India and Nigeria, that still happens today, David Umem lives in Nigeria’s Akwa Ibom state, where he works to rescue and protect children being accused of witches and wizards.

DAVID UNEM: It is alleged that you can be the reason for anything, cancer, plane crash, HIV and AIDS. Name them, you are the course of all of those things. So they look for a victim or a scapegoat to link to this problem.

CHAKRABARTI: What can witch trials throughout the centuries and in present-day, show us about fear, conspiracy, gender, and power?

Marion Gibson joins us now. She's a professor of Renaissance and magical literature at the University of Exeter. She's written eight books on the subject of witches, and her most recent is “Witchcraft: A History in Thirteen Trials," and she joins us from Plymouth in the United Kingdom.

Professor Gibson, welcome to On Point.

MARION GIBSON: Hello Meghna. Thank you for inviting me.

CHAKRABARTI: So actually, first of all, just coming off of what David Umem there said about the current day targeting of people in Nigeria, and the accusing them of being witches. What do you think is one of the major constant threads that ties what's happening today in certain places with very ancient or even millennia old accusations of witchcraft?

GIBSON: I think they're all linked by the human desire to persecute other humans, which is a depressing thing to think about, isn't it? But when you look back over the last 700, 800 years of human history, you find over and over again that the witch is a figure who is marginalized for some reason, who is picked on for some reason.

And that can be to do with gender or ethnicity or relative levels of poverty, or it can be to do with somebody just being disliked by their community. You see it over and over again, and I was really interested to explore that. And it's really interesting to hear people talk about it happening to them today, because this is absolutely not just something for the history books.

CHAKRABARTI: Later in the show, we're going to actually hear from another Nigerian who's working to save children who are being accused of witchcraft. So we're going to return to the present day. But Marion, first of all, I note that your new book is "A History in 13 Trials," I'm going to presume that the number was deliberately chosen.

GIBSON: Yes, it was, yes it's a witchy number, isn't it?

CHAKRABARTI: (LAUGHS)

GIBSON: So it seemed like the right one.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, good. I just wanted to double check that I wasn't just projecting some sort of presumption there, but so let's go back to one of the trials that you talk about in your book. It's actually one that takes place in the early 17th century.

So 1620, in what is now Norway, but was then called Finnmark. So tell us about this person and this trial.

GIBSON: That's right. So I thought this was a really interesting trial for people to hear about. You often hear about trials in England, in America and indeed in contemporary Africa and around the world.

But this is a trial in Northern Norway, the Finnmark region. And the first person to be accused is also quite surprising. She's an indigenous woman. So the people who live around the Arctic Circle, including in North America. Here, they're referred to as the Sámi People. And this woman was some kind of diviner, perhaps somebody who believed she had power to foresee the future and she knew things that other people didn't know. And onto her was projected all this fear about this supposed magical knowledge.

But also, I think a lot of racialized fear, a lot of concern about what are these Sámi people up to. So people come up from Southern Europe, they move through Norway and Sweden, and they encounter the indigenous people there. And one of the first things they think is these people have a real mastery of this landscape.

They are different from us. They look different from us.

CHAKRABARTI: They were right about that.

GIBSON: Yeah. They were.

CHAKRABARTI: The Europeans didn't have that mastery at that time, so.

GIBSON: No, they didn't. And they brought with them Christian assumptions about the way that the world worked, which actually weren't that helpful in that environment.

It was not a sympathetic environment. It was not about to deliver to them crops and resources and minerals and all the stuff that they wanted. And I think out of that, grew a fear of the indigenous people. So this woman was accused of witchcraft.

CHAKRABARTI: And what happened to her? I'm afraid it's not a very happy story.

Some of the ones in the book are quite happy, people escape from their trials in all sorts of inventive ways. But this one, I'm afraid she was thrown into the Sea of Northern Norway, which, you know, must have been a horrible experience in itself. Terribly cold, terribly frightening. It's quite possible that she couldn't swim, but she floated on the water and that was a classic test that people applied to witches.

If you floated, they thought that you were guilty of witchcraft. If you sank, they would try to pull you out. But of course, many people didn't survive that ordeal. So she was judged to be ready to be trying for witchcraft, and she was found guilty and a lot of other women in her community were found guilty alongside of her.

And I'm afraid she was burned as a witch.

CHAKRABARTI: This early example involves a woman. Historically, even as far back as you've been able to research, in terms of the persecution of alleged witches, has it been predominantly against women?

GIBSON: Yes, I'm afraid it has, and it's really clear too.

So the centuries of the mass witch trials are basically the 15th to the 18th century. And in all of the jurisdictions that historians have studied, taken all together in that time, about 75% of the people who were accused and prosecuted are women. So it's a really a big preponderance.

And in some cases, you find it's up to 90% or even 100%.

CHAKRABARTI: And why is that?

GIBSON: I think it's all sorts of reasons. I think people associate, as in the story I was just telling, I think people associate magic with having certain kinds of special knowledge, specialized knowledge, perhaps not available to the people who regard themselves as otherwise dominant in that society.

If you've got knowledge of processes of childbirth, or certain kinds of medicine or women's health, all of those kinds of things might attract suspicion to you. But also, I think there is a fear of women themselves of their bodies, of their sexuality. And if you live, again, in a very patriarchal, male-dominated society where women don't have access to becoming church ministers, they don't have access to education, they don't have access to large parts of the legal system.

All of the judges, all of the juries are male. It seems quite likely that group would be regarded as a secondary group, as a sort of outer group. And if they don't have the sort of secular, everyday practical power that you would hope that they would've done, but they didn't. Maybe people start to suspect they have other kinds of power.

That they're rebellious. They're subversive, and that they're turning to the devil or they're turning to magical powers, ill-defined as those might be, to get the power that's been denied to them. Those seem to me to be the key factors.

CHAKRABARTI: Do you know, so I also wonder, I think there's a line of feminist thinking that says in terms of power and the projection of male power onto female power, that part of it may be due to the fact that women are the ones who can carry and give birth to new life, right?

And that is a power that men will never have. They're never going to give birth to children. And that sort of capacity to create life, along with, as you were saying, existential challenges and perhaps being on the fringes of society, that there's something fundamental to femaleness that perhaps men in power had found threatening.

GIBSON: I think that's quite fair. And when you look at the level of medical knowledge that people would've had in the 15th to 18th centuries, it must have seemed very mysterious to them, this process of conception and birth. And I'm not sure that they could completely compute it, and I think it may have seemed threatening to them.

It is quite noticeable that a lot of the people who are accused are involved in medical practice in some way. It's something historians are struggle with. They've not always wanted to talk about this. But I think it is worth talking about, because when you really dig into the cases, as I do in the book, you see quite often people are saying, "Oh, I made an ointment for my neighbor."

Or, "Oh, I was a midwife for my neighbor." Or "I fell out with my neighbor because she wouldn't let me be a midwife for her." And I think those things are really important, as you say.

CHAKRABARTI: In some of the cases that you look at, does this also clash, you hinted at it regarding the case of the Sámi woman, but does it clash also with Christianity?

Because, you know, the idea that if God is supposed to be the one that heals, and yet we have this woman here who has some sort of not deeper knowledge of nature, that could be witchery.

GIBSON: Yes, I think so. And some of the healers used Christian prayers as part of their practice. The irony is they thought of themselves as being good Christians, and I'm sure they were in many cases, but they used prayers that were really only supposed to be accessible to male clergy.

And that seemed threatening at the time.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. Marion Gibson, you're actually bringing back to mind a season of Outlander for me, but I don't know if you've ever seen this show, have you?

GIBSON: Yes, I have. And one of the trials I talk about in the book is the trial that you see in Outlander.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, then later in the show we're going to talk about it.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: Professor Gibson, what I'd like to do is jump back forward into the present now. Because the connections between history and what's happening today regarding accusations of witchcraft is very, are very powerful.

And the persecution of alleged witches is by no means a thing of the past. So let's take a moment to listen to Mary. She's a child living in the Nigerian state of Akwa Ibom and she recently spoke with the German public television network, DW Documentary, and that was in 2022. And she said her father accused her of being a witch after her mother left the family.

MARY: He actually wanted to take my life. He tied me up. My neighbor that was around rescued me that day, so he actually asked me that I shouldn't return home again. And my dad was also in support that I shouldn't return again, and I left because of the fear.

CHAKRABARTI: That's Mary speaking to the German Television network, DW documentary.

Joining us now from Nigeria is Leo Igwe, director of Advocacy for Alleged Witches, an organization that works to defend the rights of alleged witches in African countries. Leo Igwe, welcome to On Point.

LEO IGWE: Yes. Thank you for having me.

CHAKRABARTI: May you please first describe, Mary sounded very young.

She was a child. She is a child. How widespread is the act is accusing children of witchcraft in Nigeria?

IGWE: How widespread usually is a question that, you know, tries to get us to understand something somehow that is visible. What happens is that accusations of children largely happen behind walls and just like Barry described, this was happening within the family walls.

So if it's difficult to track, yes. What happens is that believe that children could be witches, adults could be witches, is widespread, but it is difficult to track places, time, individuals who are often at the receiving end of these beliefs. But we have recently known that over 15,000 children are accused or maltreated in the name of witchcraft, believe in Nigeria.

But we always say that this might actually be an underestimation. Because the victims are those who are in position, they cannot speak for themselves. It's only when there are extreme cases, when they're tortured or when, as in the case of Mary, and never draws attention of the authorities, that one begins to understand the severity of the situation.

So it happens behind the wall of silence, sorry, it happens behind the wall, the walls, family walls. So it's difficult actually to ascertain how widespread it is.

CHAKRABARTI: I see. Your point is very well taken. But some of the research that we've been able to find about exactly how widespread it is, with the caveat in mind that you said that it's taking place behind closed doors.

There's at least one from the African Child Policy Forum, that in 2022 found that hundreds of thousands of children across the entire continent are accused of witchcraft each year. But Leo, why children?

IGWE: Yeah. That is a very interesting question. Why children? What happens is that, first of all, witchcraft accusation is a political issue.

Is a phenomenal link to power relation. So those who are in weaker social, political, or social, cultural positions are often at the receiving end of accusations. Look, witchcraft suspicion is widespread, is part and parcel of religious upbringing. The religious, social upbringing of many people in Nigeria or many people in this part of the world.

But what happens is that how many people manifest them? How many people use this narrative to make sense of their situation? It is usually those who find themselves in a position where they can place the level on others, and these are vulnerable people, so children are usually vulnerable, especially when they find themselves within families where their parents can actually place this label on them with impunity.

So yes, why children? Because which context the accusation has a political dimension and is only placed on those. Or people who are accused are those who can be accused.

CHAKRABARTI: I see. And children belong to this category, and children are very vulnerable and unable to respond to such accusations in the face of the age, the gender, the power differentials and the fact that, as we heard from Mary, sometimes those accusations come from their own family members, but Leo, hold on for just one second here. Professor Gibson, may I turn back to you in your study of witchcraft through the centuries. And we talked about women earlier, have you found that children were also frequently accused across the centuries?

GIBSON: Not as much. No.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay.

GIBSON: It's really interesting what Leo says, and historians have worried about what that difference is. You know, why children are more likely to be accused today strangely than they would've been in the past, and it seems quite likely that children were actually more disempowered in the past, they were told to keep silent.

They were told to do what their parents said and so on. You can imagine in the classic European religious household; children are to be seen and not heard. But today actually children are perhaps a little more powerful than adults are used to, for example, they can have cell phones, they can travel to places where they wouldn't previously have traveled to.

Because there is more transport today, they can use the internet to travel in other ways and gain information that may be a surprise to adults in their community. So one of the things people are speculated about is yes, children most certainly are disempowered, and they're scapegoated and picked on for those reasons in contemporary communities, but perhaps that's partly because adults have a sneaking suspicion that they do have knowledge that adults don't have, that they have some sort of power, which is secret from adults.

The power of the internet, the power of the app, the power of the cell phone. Maybe it's something to do with that. I don't know what Leo thinks of that, but that's certainly something that historians have suggested might be the case.

CHAKRABARTI: Leo, would you like to respond to that?

IGWE: Yes I think that to some extent, she's right.

But what happens is that in my own part of the world, many of these children come from poor homes. But what happens today is that homes are no longer as isolated as it used to be. So that sometimes people leave, like Mary was living in situation where the neighbor was aware of what was going on.

So many of these children who live in poor homes, sometimes they live in poor crowded areas that sometimes what happens to them gets filtered out or somebody gets to know about it, somebody crossing by, or somebody who hears their cry because they live in shanty apartments, not world exclusive places.

So sometimes the information, goes out and neighbors get to know. So these children are not as isolated as they were in the past when they were just restricted to their homes and their parents. So this is how I could explain it, at our end here, we have many children don't yet have access to the internet compared to children in other parts of the world.

CHAKRABARTI: Mr. Igwe, if I could just take a step back here for a second. I imagine that upon hearing that we have focused temporarily on Africa as a place of ongoing accusations of witchcraft that many people listening to this might think, this is nothing more than the continuing specter of colonialism. That we're only turning to Africa now as a means of saying, look at those Nigerians, for example. They're still so backward that they accuse people, of young children of witchcraft and it's just a happy internet-based television positive phenomenon in the United States. Now, I just want to assure listeners that's not at all our intention here.

There's no presumption at all that just because there are different places in the world where witchcraft is still an issue that it implies some kind of backwardness. But first of all, Mr. Igwe. I wonder what you think about that. And second, how would you explain why there is the continued persistence of fear of witchcraft in Nigeria.

IGWE: Okay. First of all, to the first issue, look, that people could accuse you of racism or colonialism. I have noticed that it has stopped a lot of people from calling out witchcraft accusation. Calling it out and giving it the name that it deserves, which is something that we should abandon. Something that is horrific, something that should not be associated with Africa or with humanity in this 21st century.

What I'm saying here is this, we should not, because one could accuse us of colonialism, tolerate, condone, minimize the atrocities going on here. It is frustrating our campaign, because it's not helping us galvanize, it's not helping us get together, seek, work with people, mobilize the necessary global will and efforts to address this problem.

So what I'm saying here now is that we should not relent, we should not step back. Because some people somewhere could accuse, it may be any Western organization or radio station of colonialism or racism, please. The lives of alleged witches in Africa did matter, and we should go all out, deploy any kind of mechanism to make sure that we banish it and we stop witch hunting, in the region.

CHAKRABARTI: Mr. Igwe, can I just jump in for a second then? I definitely want to hear your answer to the second part of my question, but I hear you saying quite clearly to people, get over your white guilt because it's preventing people like you from doing the work of confronting this continuing disturbing reality that's hurting many Nigerians.

IGWE: Yes.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay.

IGWE: Yes. That is it. It's not just haunting Nigerians. It's haunting Malawians. It's Haunting Zimbabweans. It's haunting Zambians. South Africans. Go online. We are literally overwhelmed because few of us here keep speaking and then nobody wants to join us because a lot of people don't want to join us from the West because they don't want to be accused of neocolonialism or racism.

And as a result of that, with very limited resources, we are overwhelmed. We cannot actually respond to the enormity of the task here we confront. So what I'm saying is this, please let us not move back because of the fact that we could be accused of colonialism. Because the children of these people will be grateful to anybody, Black or white.

Who goes out there to make the necessary noise, mobilize the world and make sure that their parents and their children are not brutally killed as is currently the case in Nigeria and other parts of the region.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So Mr. Igwe, in a way, in a manner to get to this, your answer to the second part of my question, I'd actually like to just give another example of contemporary accusations of witchcraft and where they can come from in Africa. So in 2009, in The Gambia, then-President Yahya Jammeh ordered a witch hunt campaign. He was the president at that time, and hundreds of people were reportedly kidnapped as a part of it. So here are some of the survivors of that witch hunt speaking in a 2021 video produced by Gambian Media Company, State of Mic.

(TRANSLATION)

In there, you hear voices saying, after they took my father and gave him herbs, he felt sick, and when he came back, some people were scared to visit him because everyone thought he was a wizard.

Second voice. Usually when there are social gatherings in the community, women would assist each other in the preparations. But afterward, whoever was a part of the incident was avoided and pointed at by other women.

Voice number three. I used to sell food before the incident, but after when I sold food, many stopped buying from me because they were all scared of me.

CHAKRABARTI: So Mr. Igwe. If we still have incidents where even the president of an African nation calls for a kind of witch hunt, why do you think that continues to happen?

And perhaps more importantly, what do people like you need to support your work to eliminate this practice in African nations?

IGWE: First of all, yes. I was in Gambia when this happened, and I visited some of the victims. In rural Gambia and I heard their stories, how some of them were tortured and a few of them, of course some died, and a few were able to come back alive. But what happens is that when it happens, number one, yes. What is the reaction of the international community? Was there a widespread condemnation? Or people ignore it and think, yeah, it's an African thing. Our heart is broken because the international community.

Now, look at this situation as an African thing because they think that witch hunting in Africa means a different thing from witch hunting in Europe. Because of the fact that, Oh, this happened 300 years ago now. This is still taking place. Now, Western anthropologists have explained that witch hunting is beneficial, is useful, has domestic value.

By so doing, minimizing, and weakening the global political will that could be rallied against people like Yahya Jammeh when he was in power, what he did. Yes. These are some of the things that tyrants, dictators, like we know Yahya Jammeh was, could do. But what did the civilized world do? That is the most important thing.

They ignored it, and we just hear this documentation, what we expected. Advocates like me, widespread condemnation, naming and shaming, and getting him to answer for his crimes. I don't know why some former heads of states could be taken to the head to answer for their crime. Somebody like Yahya Jammeh could not be taken to the Hague to answer for this very crime.

So there is also another layer of responsibility on the part of other members of the international community for ignoring it, for looking the other way, for not holding him accountable. There is a way that reinforces the situation, and there's the way that this betrays. Advocates like me will feel betrayed by the international community as a result of how they reacted.

Now what you asked, what do we need or what can we need? What we need is that, first of all, the idea that witch-hunting in Africa is beneficial, should be dropped. This is a kind of a representation of African witch-hunting that has continued to undermine our work and efforts. The global community should understand that the lives of victims of witch-hunting in Africa, they matter and they're also equal.

To lives of other people. Now if people persecuted Uganda American or Europeans, I know how the reaction would be. And we remember during the pandemic how the world rallied together to make sure that everybody was on the same page in fighting the pandemic. Why is it different in this case? Why is it different when it comes to witch hunting? Is it because it is happening dominantly in Africa? Now, if the world could rally together to fight the pandemic.

The war should also rally together to fight witch hunting in Africa or any other place where it's happening.

CHAKRABARTI: Mr. Igwe. Leo Igwe, director of Advocacy for Alleged Witches. It's an organization that works to defend rights of alleged witches in African countries. I can't thank you enough for joining us today and Marion Gibson.

I would love to hear your response to all that Mr. Igwe brought to us, but we'll hear that after this break.

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: Professor Gibson, I deeply appreciate you listening along with me to Leo Igwe in the previous segment because the reason why we wanted to bring him on was to give a very visceral sense about this idea of witchcraft in the western mind is now often romanticized or even celebrated. We'll hear about how the internet is expanding that in a few minutes, but in truth, accusations and campaigns against witchcraft. Now and historically are campaigns of cruelty and persecution, that not just harm, but kill many people.

And that's still going on today. So hearing Leo Igwe's passion about, we have to do something about this. I wanted to reground us in the reality of what a witchcraft campaign is. What did you hear? In what he was saying about what's happening in Africa now versus your examination historically of persecution against alleged witches.

GIBSON: It was great to hear that, wasn't it? And it was such a powerful call for help and a call to arms, and I think he's absolutely right. More should be being done about this. I don't think it matters whether somebody was killed, murdered, really, as a witch in 1624 or 1924 or 2024.

It's the same type of injustice and persecution and it's groundless. That's one of the things that I think is so terrible about it. People can of course, be absolutely free to believe in magic if they want to do but the idea that you would kill another human being because you believed that they had attacked you magically, it's not something we can just stand by and feel okay about, whether that's in history or it's today.

CHAKRABARTI: So this takes us now to how part of witchcraft, again, not anti-witch or wizard campaigns, but just the desire to identify as a witch or the allure of what we consider to be witchcraft is so strong still today. First of all, Professor Gibson, how would you define what people think of when they're drawn to this idea of witchcraft now?

GIBSON: Yes. I think it's about reversing that old stereotype, really. The idea that a witch is a dangerous person, usually a dangerous woman, somebody who is maybe poor and outcast and has been forced out of their community, who is a difficult person to deal with, maybe a heretic. All of those kind of things are reversed really in the modern witchcraft movement.

People embrace the idea that they are an empowered woman or an empowered person, and that they have different religious views, maybe from the mainstream and that they have a concern for other things than, for example, capitalism. So maybe they're an environmental activist. Or, they advocate for animal rights or something like that.

The modern witchcraft movement is really the other side of the coin of historical witch trials, because it reclaims all the things that the witch trials thought were wicked and demonic.

CHAKRABARTI: So let's listen to a little bit about how that reclaiming is going on, especially in the age of digital media. Professor Gibson, as we mentioned earlier in the show, a growing number of people in the U.S. specifically are embracing witchcraft, and we heard from one of them, Shawn Engel, who describes herself as a professional witch.

ENGEL: Ritual is huge for me. I run a coven, I'm a high priestess of a coven, and so we do rituals together every month.

But in my own practice, I will do manifestation rituals during a new moon and banishment rituals during a full moon. Calling in any kind of energy that I desire. Doesn't even have to be like a book deal, which I did manifest.

CHAKRABARTI: So roughly every month, Shawn says she'll wave a wand of European sage and lavender around her small New York City apartment in a clockwise motion, and that calls in good energy into her apartment.

She's also a big believer in astrology and in reading tarot cards. Eight years ago, Shawn turned her witchcraft practice into a job, and her business is called Witchy Wisdoms.

ENGEL: I do live readings. For people at large events, large scale events. I also do online readings, and so what you'll find when you immerse yourself in this practice is that you'll have cards that quote-unquote haunt you, and they'll keep showing up for you in readings, and it's generally a lesson you're not learning.

I've done a lot within the witchcraft community and provide different spells and services to people that need it. An hour-long tarot card reading with Shawn, whether in person or online costs $155 according to her website. She'll also send you an emailed reading for $75.

CHAKRABARTI: And like she said earlier, Shawn manifested a book deal. She's now written four books on witchcraft, including “The Power of Hex: Spells, Incantations, Rituals” and “Cosmopolitan’s Love Spells: Rituals and Incantations for Getting the Relationship You Want.” And Shawn says she's thrilled to see such a growing interest in witchcraft.

ENGEL: The internet has definitely become a place where we can take the cloak off in a way. And there really has always been interest, and I equate that a lot to women, mainly, feeling powerless and wanting to regain a sense of control and power and being fed up with the way that we've been conditioned and treated.

And that's sexy no matter who you are or where you are. So when it comes into your purview, then yeah, you'll get to see the popularity of it.

CHAKRABARTI: But Shawn says she also recognizes how lucky she is to live in the United States where witchcraft is not still persecuted.

ENGEL: I am an attractive, young white woman in America, so I have an immense amount of privilege to be able to monetize my practice.

And for those that don't, and those that get persecuted, it absolutely breaks my heart. And it is in the same way that women's rights are taken away from all over the world. People see what happens when women, or women identifying femme are empowered. We are very powerful. So you know, as it breaks my heart, I feel like the work that we do here, that I can do, and especially within my Instagram as it can be a toxic space, is to just keep talking about it.

CHAKRABARTI: So that's Shawn Engel, self-described professional witch and founder and owner of the business, Witchy Wisdoms, and more power to Shawn for practicing what she believes in. But Professor Gibson, I also find Shawn as a maybe particularly American example of the ability to practice one's belief in the digital age, met with capitalism. Those, they make wonderful bedfellows in this country. I'm just wondering what you think.

GIBSON: Yes, they do. Witchcraft is a big business now actually, but it's not just in America. It is actually all around the world too. So I think that's important and yes, good for her if she finds spiritual empowerment and personal empowerment.

In magic and witchcraft and wants to reclaim the image of the witch, then I think that's great. Actually, you talked earlier about how that's also been done in TV and film and online, more generally on TikTok and Instagram. This does appeal to an awful lot of people today. The witch feels like a very relevant figure to me.

CHAKRABARTI: I think what Shawn's getting at it, it actually echoes back to the very first case that we talked about. It's reclaiming the sense of power, not wanting to be the victim of disempowerment, right? She spoke to that directly. And whether in this case for her, it's through identifying as a witch, that desire to feel empowered in 21st century Western countries, especially amongst women, is very powerful or strong, I should say.

But now we're getting to the point Professor Gibson, where I just can't resist. Because you just mentioned TV again, I have to admit I was so focused on the historical cases in your book that I didn't even realize you'd written about Outlander and the trial there that's featured in that show.

GISON: Yes, I do. So the second trial I look at in the book is the trial on which the Outlander trial, which was a real witch trial, is based, you'll remember the character is called Geillis Duncan.

CHAKRABARTI: Yes.

GIBSON: She was a real Scottish woman who lived in the 1580s and was indeed executed as a witch in the early 1590s.

So I've actually written about that story. And one of the things I thought that Outlander did so interestingly was resurrect her and reclaim her and give her a kind of magical afterlife in that show, which I think was really powerful. And the fact that you remember it as being really powerful, I think makes the point.

CHAKRABARTI: I was captivated by that season.

Now, honestly, quite all of them, she meets an unfortunate end later in the show, but that is so fascinating. Okay, there's another case I want to just briefly talk about because here I am based in the United States and New England, nonetheless. And so obviously the most famous cases in America are the Salem witch trials, but when you talk about Salem, you talk about a completely different person who was also persecuted.

Can you tell us that story quickly?

GIBSON: Yes, I did want to do that because Salem is so well known, and I wanted to tell the story rather differently. So I focused on the woman that listeners might know as Tituba, but I've tried to give her back what I think was more like her original name, which is Tatabay, and she again is an indigenous woman like the woman that we talked about earlier in Northern Norway, and I think she's picked upon as the first of the Salem Witches, the first person to be accused, partly because of that ethnic difference from the people around her. I think also because she was a woman.

And because people associated, there for her, with all of those kind of magical attributes that they associated the Sámi woman with earlier, somebody who was different, somebody who was from outside, somebody who seemed to have some religious differences from the people around her, who was associated a bit more with a kind of wider landscape and the country and the place where she came from, which is probably South America rather than North America, but was nevertheless this new world.

She seemed to the pirates and settlers to be somebody who maybe had some power that they didn't like, but in reality, of course, she was a very disempowered person, a former enslaved person, somebody who'd been transported a long way from her home community and was living in servitude in Salem Village.

So I wanted, as I've tried to with all the stories in the book, to as much as possible recover her words, her story, to tell the story from her point of view as an accused person and somebody who would otherwise have been silenced by history.

CHAKRABARTI: So you close the book bringing us very much into the present.

And a couple things come to mind. One of them is just the term witch hunt, right? For so long, it's been so fully embedded into common parlance that people very freely apply it. If they simply just feel like they're being unfairly accused, they'll accuse everyone else of participating in a witch hunt.

So it's focused meaning has been significantly diluted. It's often used in politics in the United States, I will say, which is why I was so fascinated to see that chapter 13 of your book has to do with Stormy Daniels, the trial of Stormy Daniels, witchcraft in North America. And people might remember Stormy Daniels, of course, as the adult sex worker who had many interactions with former President Donald Trump.

Even wrote a book about it, sued Donald Trump, etc. Why is the culmination of your book with Stormy Daniels, Professor Gibson?

GIBSON: I just thought it was a really interesting word to tell the story of that modern use of the word witch hunt. Because you're right, it's everywhere, isn't it? It's used in Britain as well as America, and I thought can we tell this story from a different angle?

One of the things I didn't know about Stormy Daniels when I started to research Donald Trump's use of the word witch hunt, is that Stormy actually identifies as a witch. She's the modern pagan, she's a tarot reader, like the person that you just talked to, and I thought isn't that interesting? We've actually got one person here who is claiming to be the victim of a witch hunt, and we've got one person who actually says that she's a witch.

What can we do with that story? So again, I wanted to tell it from her point of view and to get people to really think about that term witch hunt, which as you say, we've become a little bit blase about, why are we still using it? Why? Why do we still turn to the image of the witch when we want to talk about persecution?

And I think that's one of the things the book can do, I think, is take people on that journey over time. What did witch mean in the 15th century? What did it mean in the 17th? What about the early 20th? What about now?

CHAKRABARTI: But tell me a little bit more, what did you say from the Stormy Daniels point of view?

It does come as a surprise to me that she, I think you said is a practicing Pagan, right?

GIBSON: Yes. Yeah. It came as a surprise to me too. When I first looked at her. I wanted to talk about the way that people can, I think, unfairly claim to be the victim of a witch hunt. When I think of a witch hunter, looking back over all the historical research that I've done, I see on the whole a male person, somebody who's in a position of power, maybe a state governor, maybe a king, those kinds of examples are all in my book. Somebody who is actually very well respected in the society that they sometimes even govern.

Somebody who's probably quite rich, well connected, and so on. I don't see somebody, Donald Trump, I see somebody like Stormy Daniels who is set apart by her choice of profession, who is mocked and reviled sometimes by people, who is a woman and who has a certain position in her society because of that, and as somebody who believes in magic, as somebody who identifies herself with magic.

So I wanted to look at the story the other way around and ask people to think for themselves really. Who is the witch here? What is going on here? Who is the witch hunter? How do you feel about this use of the word witch in contemporary society?

This program aired on February 16, 2024.