Advertisement

Commentary

The 'Shame And Rage' Of Being A Minority In America Kept Me Silent. Not Anymore

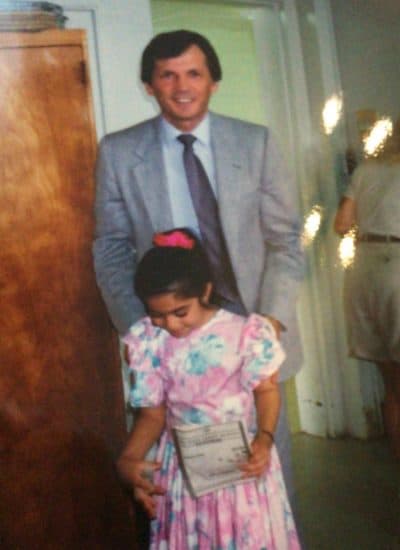

It is 1994. I am running for president of the student-run safety patrol. We’re the kids who help other elementary schoolers cross the streets in the vicinity of the school. I take my responsibilities very seriously, mustering bravery when I have to walk to my post, the crosswalk past the house with the loud Doberman who weighs more than I do. I lose the election to the most popular girl in school, a blond-haired, blue-eyed all-American athlete. She is as different as possible from me — a dark-haired, mousy, awkward Pakistani kid who had to take English as a second language in kindergarten (even though I was born in America) because my immigrant parents’ grasp of English was too limited to teach me fluency.

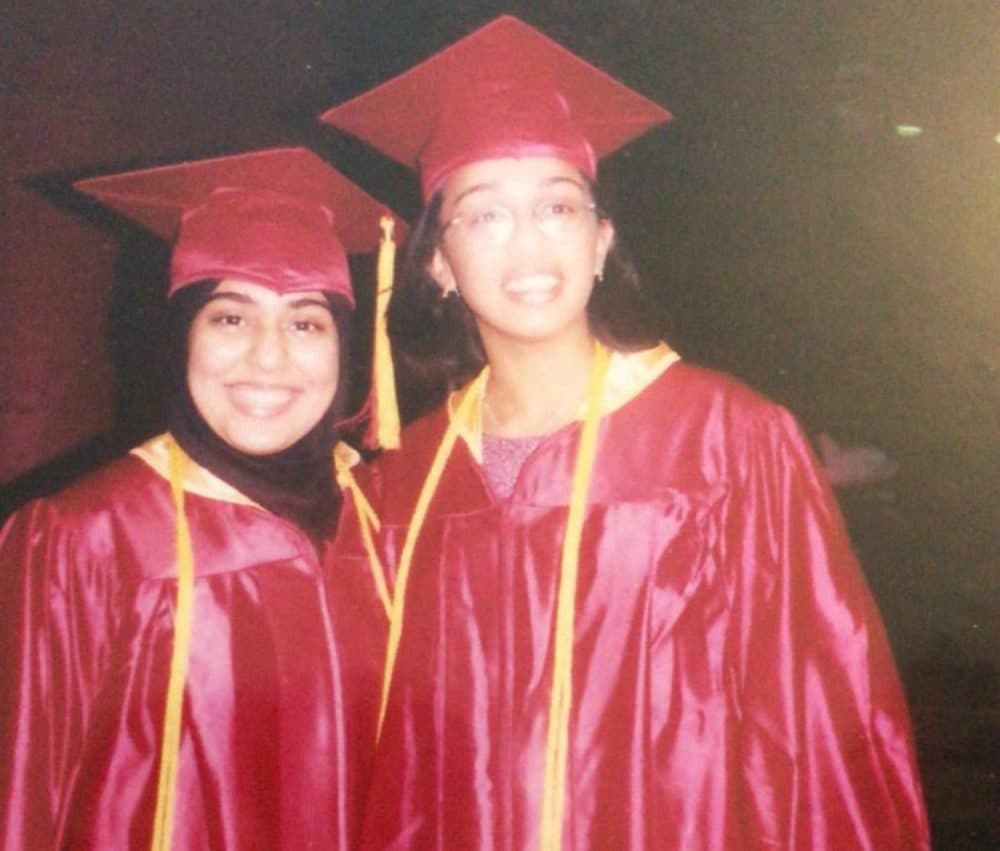

It is 2001, and 9/11 happens. I’m a senior in high school. Classmates accuse “my people” of being terrorists, and I am called a raghead and threatened while I walk home. I am our class salutatorian, and the typical tradition is to honor the valedictorian and salutatorian as the first “seniors of the month.” But it is September 2001. The all-American blond-haired, blue-eyed girl — ironically, the very same one who I lost the student safety patrol election to back in 1994 — is named September “Senior of the Month,” although her academic and extracurricular credentials don’t compare to mine.

That same year, my white guidance counselors advise me not to apply to Ivy League colleges because it would be a waste of my parents’ money. I ignore them and apply only to Ivy League colleges. When I receive acceptance letters from all of them, I am accused of taking the spot of my white classmate who was waitlisted.

It is 2011, and I begin my training in obstetrics and gynecology. For the next four years, patients and staff will confuse me for a nurse, a janitor, the food delivery staff — for everyone except for who I really am: a doctor.

It is 2015, and terrorists attack Paris. I am the obstetrician on call in Boston, working a 24-hour shift on labor and delivery. I am the only Muslim woman and one of the few attending physicians of color in our department. I am horrified while watching the attacks unfold on the television in the break room. A nurse who is also watching comments that the attacks occurred because “there are a lot of Muslims there” while looking directly at me. I leave the room.

It is 2016, and Donald Trump wins the White House, after running on a platform of racism, hatred, misogyny and lies. He spent a year advocating for a Muslim database and surveillance of mosques, because “Islam hates us.” I have recurrent nightmares of people coming into my home and killing me and my family. I stop watching the news.

It is 2017, and my 3-year old son asks me why he doesn’t have blonde hair and blue eyes like his classmates. “Why is my hair so darkish, darkish brown?” he wants to know.

It is 2020, and I am now in a position of privilege. I have three Harvard degrees on my resume and am a physician with a faculty appointment at Harvard Medical School.

A worldwide pandemic occurs. In this country, it kills Black people at a disproportionately high rate compared to any other group.

About three months into the pandemic, George Floyd is killed by police in Minneapolis. He is one of the many Black people who have been killed in a variety of ways by systemic racism and police brutality.

I am the model minority. I witness injustice but stay silent, justifying my silences ...

Meanwhile, Black mothers continue to die at higher rates in childbirth than any other women in this country. My Black pregnant patients are aware of these disturbing statistics. For them, birth is uniquely dangerous. They should be celebrating bringing new life into this world, but instead, they are worried. They are worried first about their own survival in childbirth, and second about the survival of their Black children in the world. They ask me whether I, as their obstetrician, can guarantee them a safe delivery. No matter how much I care, I cannot, because what kills them has been incorporated into the very building blocks of America.

I live with my children and husband in the suburbs in a house with a white picket fence. I am the model minority. I witness injustice but stay silent, justifying my silences — “I’m too busy; I have a lot of responsibilities.”

I remain silent when a healthcare provider makes a dismissive comment about my patient, a Black mother forced to be a single parent because her partner is incarcerated. I remain silent when a patient calls my office to ask what my race is, and then refuses to see me because I am not white.

A Black woman comes to my office; this is her first pregnancy, and she chose me as her ob/gyn because I am a woman of color. She hopes that I will be an ally.

But I have not been an ally. I have felt helpless, powerless and afraid. I have been silent because I have absorbed the prevailing cultural notions that as a woman and a person of color, my voice does not matter, and that I should remain silent.

I look in the mirror. I look at my two beautiful brown children. I look at my patients who are women of color, and at my colleagues, residents and friends. I feel shame and rage. Shame that in my desire to be the model minority, to assimilate, to be seen as “normal” instead of the other, that I remained silent. Rage that I was systematically taught that because of my race, religion and gender, I would always be suspect as the other.

My immigrant parents, instinctively understanding that I would never be able to bridge all the distances between myself and the image of the stereotypical all-American girl, instructed me to keep my head down and work hard so that I could succeed. But at what cost does this success come, and is it meaningful, if, out of all the identities I hold, the only ones by which I am judged are: brown, Muslim, woman?

I have been silent because I have absorbed the prevailing cultural notions that as a woman and a person of color, my voice does not matter, and that I should remain silent.

In 2020, I force myself to reflect on my silence. My silence is lethal. It kills my Black patients, colleagues and friends. My silence is complicit. It enables patriarchy and white privilege. My silence is unjust. It cannot be justified.

I will never be the one with a bullhorn, leading the rally. That doesn’t mean that the only other alternative is silence that will uphold the status quo. In between these two ends, there are other ways of advocacy that will challenge the racism that has insidiously filtered down from generation to generation and that lurks beneath the placid surface of all of our lives.

So, I thank my Black patient who chose me to help her on her journey to become a mother. I tell her that it is an honor and a privilege. I will be her advocate, and I will amplify her voice.