Advertisement

Commentary

My mom, Julia Child and me

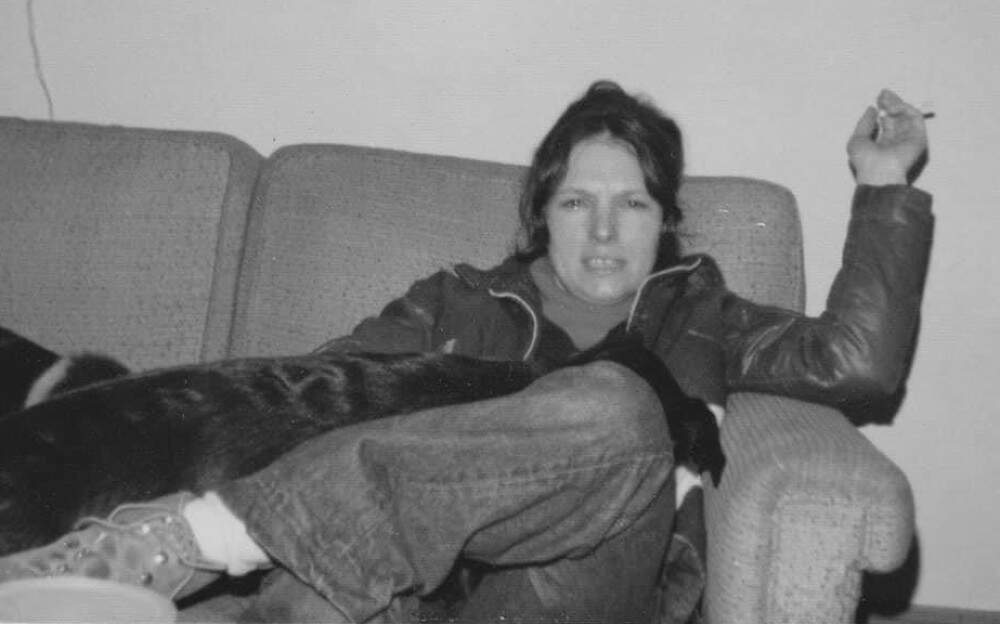

I can still see her, cigarette in mouth, a mug of coffee or cheap red wine within arm’s reach, standing at our kitchen island.

My mom is chopping, mashing, dicing. Frying, braising, sautéing. Broiling, blanching, poaching. Steaming, simmering, baking. Most of all, she is tasting, and inviting me, and my brother and my sister, to taste, too.

My mother loved to cook. She was fearless in the kitchen: experimenting, failing, trying again.

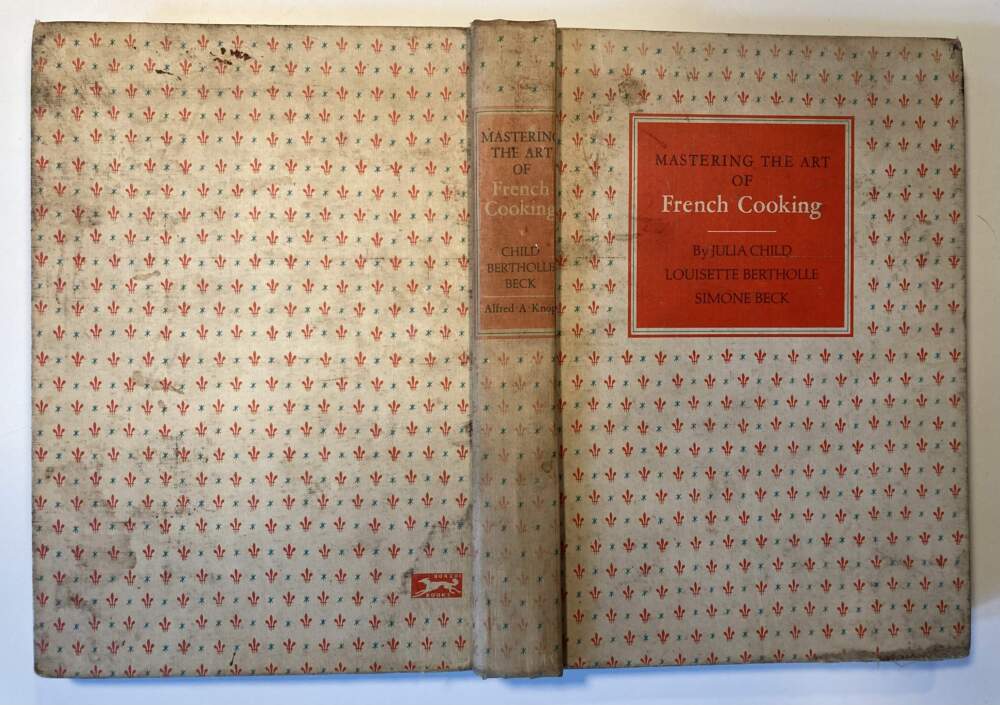

Sadly, I don't have any of my mother’s handwritten recipes. But recently, my sister passed along Mom’s beat-up copy of “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.” I had not laid eyes on the book in decades — at least since my mother’s death in 1997. And yet, leafing through its stained pages, Mom and her cooking returned to me.

“Mastering the Art of French Cooking” is the classic cooking primer Julia Child wrote with Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle in 1967. For many cooks of the era, Child blazed a gustatory trail, reorienting American taste buds towards flavors and preparations from beyond our borders. Mom was an early fan of “The French Chef,” Child’s pioneering cooking show (produced in Boston by WGBH); the program was often on TV, bringing Child’s warbling voice into our kitchen and her cookbook’s recipes to life.

Sure, Mom served us our fair share of meatloaf, tuna casserole and spaghetti. But before her brain injury in 1978, my mother hungered for ways to step out of her Ohio-bred cooking rut. She was an early adopter of international cuisine. Thanks to Julia (and the Time-Life Foods of the World cookbook series) she hosted potluck “international dinners,” where neighbors each brought over a dish inspired by a different cuisine or country. She taught us kids to love omelettes, artichokes, lobster, chile rellenos, ratatouille, zucchini bread and bananas flambé — adding a certain je ne sais quoi to our everyday meals.

Advertisement

Recently, I embarked on my own culinary-archaeological expedition. With my mom’s copy of “French Cooking” parked on the kitchen counter as my guide, I began journeying through a Proustian madeleine memory minefield. Twenty-eight years after her death, I've been re-experiencing my mother’s joy of cooking.

I can't recall exactly which of Child's dishes my mother made for us growing up. But I don’t have to. Flipping through the pages of the book, I can see which recipes she used more than others. Some pages are dog-eared. Other pages — like the recipes for Coquilles St. Jacques, pâte brisée (pastry dough), quiche Lorraine — are egg and beef streaked. Knowing her, some are probably Paul Masson-spattered and cigarette ash-smudged as well.

One of the most well-worn recipes appears on pages 79-82: sauce hollandaise. The recipe has only three ingredients— butter, egg yolk and lemon — but the four-page recipe is a battlefield of blemishes, and Julia’s warnings about the emulsion curdling, being too thick or too thin. “We feel it is of great importance that you learn how to make hollandaise by hand,” Julia advises. I haven’t mastered it yet, but I know Mom did, because I can remember the rich, tangy hollandaise she served over poached eggs and asparagus to three kids under 12. That was Mom.

In my imagination, Mom thumbs through her 684-page bible, trying to master the next challenge. Perhaps she contemplates choux, egged on by the master’s encouraging tone: “You cannot fail with puff shells.” Or she might decide to take on a more advanced culinary maneuver, following Child’s step-by-step illustrated instructions to truss chicken for roasting: “Push the needle through the carcass where the second joint and drumstick join, coming out at the corresponding point on the other side.”

I trace her progress through the recipes, her mistakes, her triumphs, scanning for where she dropped a blob of butter or dusted pages with flour. Where did her mind and imagination go? Where did she go? And where should I go next?

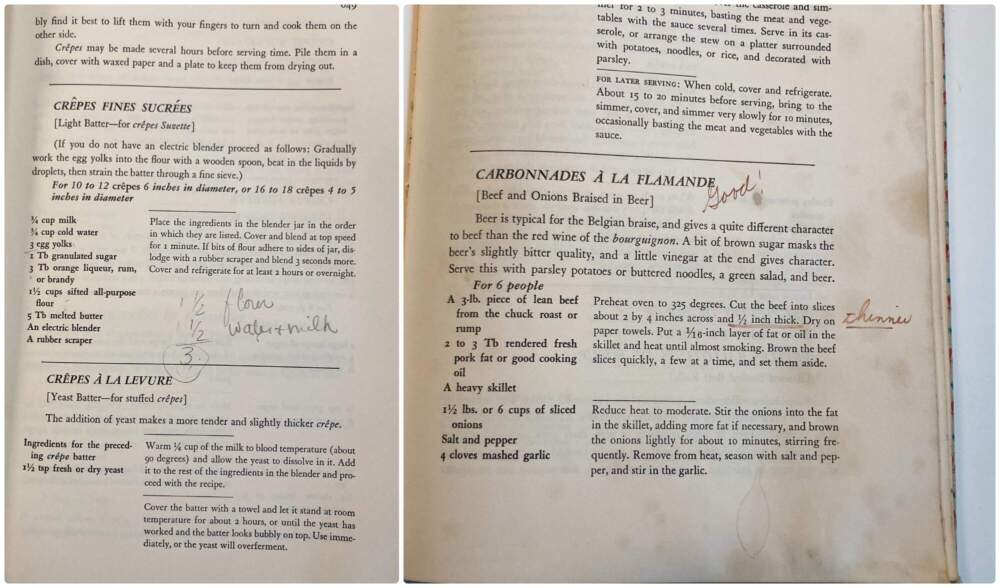

I decide to make Julia Child’s crêpes fines sucrées. On page 647, I see Mom’s faint handwriting: She has calculated the math for a double batch — “1 1 ½ flour, 1 ½ water + milk = 3” — probably because we kids loved crepes. Today, I’m making them for me and my 87-year-old father. (My mom and dad divorced in 1972.) The first few crepes are train-wreck failures. I imagine my mother dropping an f-bomb as her first batch likely misfired, too. Eventually, I pull off a few decent ones, and stuff them with cheese and asparagus. Voila! Dad and I agree they are delicious.

Paging through the cookbook again, I see another trace of Mom’s presence: next to carbonnades à la flamande (beef and onions braised in beer), the annotation “Good!” But she also offers Julia a suggestion: In the instructions for cutting the beef, she’s underlined “1/2 inch thick” and notes it should be sliced “thinner.”

I decide to tackle an adjacent recipe, beef bourguignon. As I brown the meat and add the flour, then an entire bottle of cheap red wine, I remember how my mom, a single mother who worked full-time, would leave her latchkey kids notes like: Cube potatoes and carrots. Add to pot roast in Pyrex. Cover, 350°. Be home at 5. Love, Mom.

But beef bourguignon is no everyday pot roast. Halfway into tackling it, I realize I don’t have bacon rind, mushrooms, “small white onions” or parsley. Child wants me to take the casserole on and off the stovetop and in and out of the oven. I run out of time and patience. I quickly scan the recipe, get the gist, skip some ingredients and fudge the rest. I’m not sure Julia would forgive me, but Mom surely would. A master improviser, she never followed a recipe exactly. The stew comes out just fine.

When I was 8 or 9, inspired by one of my mom’s international dinners, I concocted an elaborate meatloaf, a sort of beef Wellington with a latticework puff pastry over the top. The hands-on assembly must have appealed to me — all that cutting and interlacing pastry like constructing a project from Legos or an Erector Set. When the dinner guests arrived, they assumed Mom had baked the fancy entrée. “No,” she corrected them. “Ethan did it, all by himself.” I felt proud I had made the meatloaf (with a little bit of her help), but mostly because the cooking had taken place in her kitchen. In our kitchen.

Cooking from my mother’s favorite cookbook keeps her alive. I can feel her watching me as I dice, mince, macerate. Purée, brine, deglaze. Garnish, stir, fold. I take measure of her, stew in my regrets, marinate in her memory. I cook because I want proof of her — to feel her rise in me.

Mom, I vow to take on hollandaise soon. Thankfully, Julia offers a cheat code: Way back in 1967, she gave us permission to make that tricky sauce in a blender. “The technique is well within the capabilities of an 8-year-old child.”

Or, in my case, your 58-year-old son.

Follow Cog on Facebook and Instagram. And sign up for our newsletter, sent on Sundays. We share stories that remind you we're all part of something bigger.