Advertisement

Commentary

The Girls from Boston

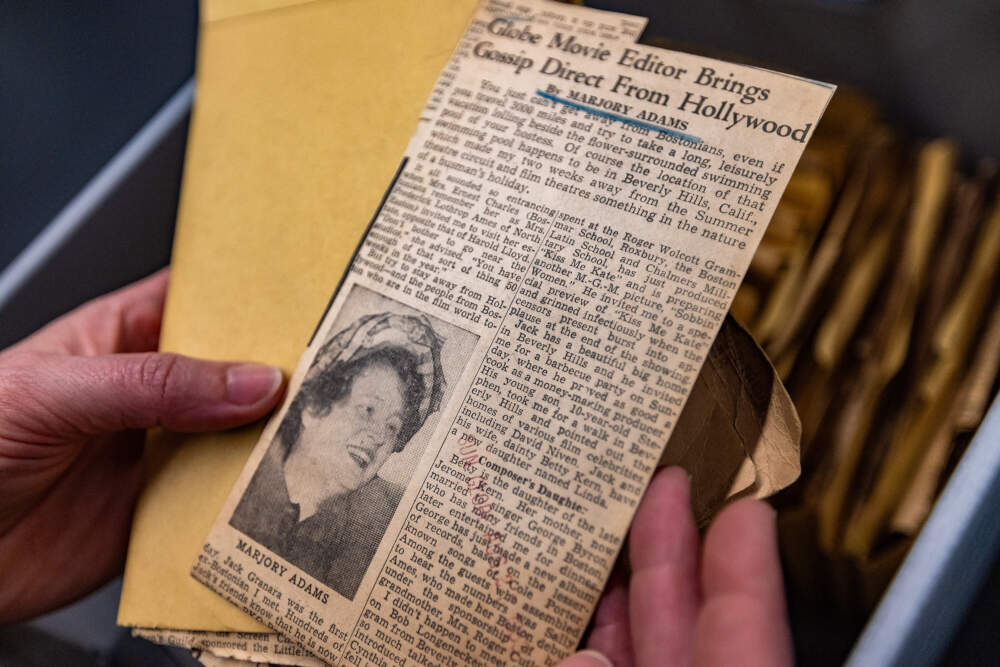

Who was she? I wondered as I examined a box stuffed with fragile, yellowed clippings of newspaper stories written decades ago by Boston Globe reporter Marjory Adams. I had just started my excavation of archival materials donated by the Globe to Northeastern University, where I work as a journalism professor. My goal was to find influential local women journalists who, because of sexism and other factors, have been overlooked. Adams was exactly the type of historical figure I’d hoped to discover — prolific, talented and nearly forgotten.

She joined the Globe in 1919 and worked the graveyard shift until a male editor, appalled at the thought of a young woman reporting on crime, reassigned her to a new beat covering the emerging film industry. At first, Adams viewed the move as a demotion. But she soon embraced the role and became the Globe’s first film critic, churning out reviews, feature stories and columns until her retirement in the 1970s. Readers adored her. The Hollywood trade press was fascinated by her. Newsroom colleagues called her “the grande dame of the editorial staff.”

Yet Adams is largely absent from history. The canonical account of the Globe’s first 100 years mentions her only in passing and misspells her first name. She has no Wikipedia page, and, as far as I know, I’m the first person to pay much attention to her career since her death in 1986.

These omissions became even more frustrating when I learned that Adams was part of a local trend. During the height of Hollywood’s Golden Age, Boston’s daily newspapers employed some of the nation’s best-known film critics. All of them were women. They tended to travel as a pack, lugging typewriters and formal gowns to movie premieres all over the world. As novelties in the male-dominated media industry, they often attracted enough attention to upstage the stars. By the 1930s, they’d earned an enduring nickname: The Girls from Boston.

“We were known in New York, Hollywood, London, Paris, Rome and even places like Stockholm and West Berlin,” Adams wrote after her retirement. “We went on junkets all over the world. And we turned out good stories.”

Adams was the group’s ringleader. The other members included Prunella Hall of the Boston Post, Helen Eager of the Boston Traveler, Elinor Hughes of the Boston Herald and Peggy Doyle of the Record American.

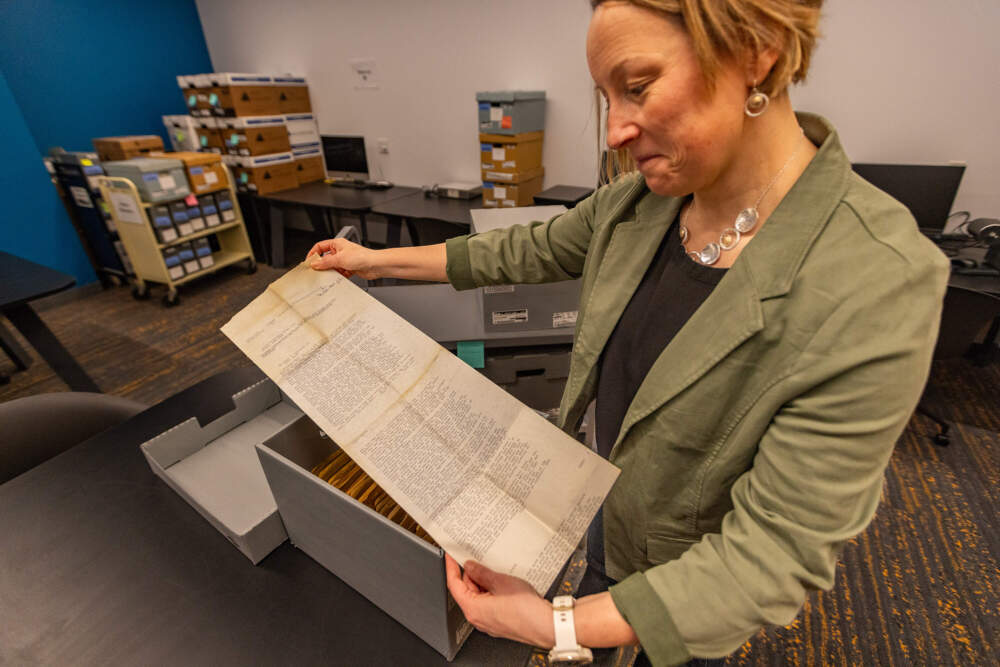

For a while, I hoped Adams and the others would be the subject of my next book. But alas, there is, too little archival material to propel a nonfiction narrative of that length. The women likely generated massive paper trails but they appear to have left very little behind. I’ve been unable to find letters, diaries or other personal artifacts necessary to give a story about these women the depth and interiority it deserves.

This lack of material is a familiar frustration for anyone documenting the contributions of women and other marginalized groups. A time period’s prevailing power structures, plus luck and the desires of surviving relatives, determine whose papers are considered important enough to save. Women’s work has historically been seen as inferior and therefore less worthy of preservation, especially in male-dominated fields like journalism.

Advertisement

Things have slowly improved in recent years thanks to organized efforts to make the formal record more inclusive, but this progress is stalling, perhaps even backsliding, under the Trump administration’s anti-DEI policies. Women’s contributions to the military and other government agencies have been obscured. Universities, afraid of losing federal funding, are removing references to women and gender from their websites. An executive order signed by Trump in late March instructs the Smithsonian and the Department of the Interior to scrub exhibits and monuments of references to racism, sexism and the struggle for LGBTQ rights.

This amounts to an intentional and ongoing erasure of women and other marginalized people from our collective memory. As I’ve watched it unfold, I’ve found myself thinking again of Adams, Doyle, Eager, Hall and Hughes. In an act of protest and remembrance, I reopened those boxes of clips, revisited my notes, spent a few more hours in the archives and pieced together this incomplete history of the Girls from Boston.

The five women first traveled together in fall 1936 on a two-week junket organized by Paramount Studios. By then, film criticism was well-established in American journalism, and critics helped to connect movie stars to growing fan bases.

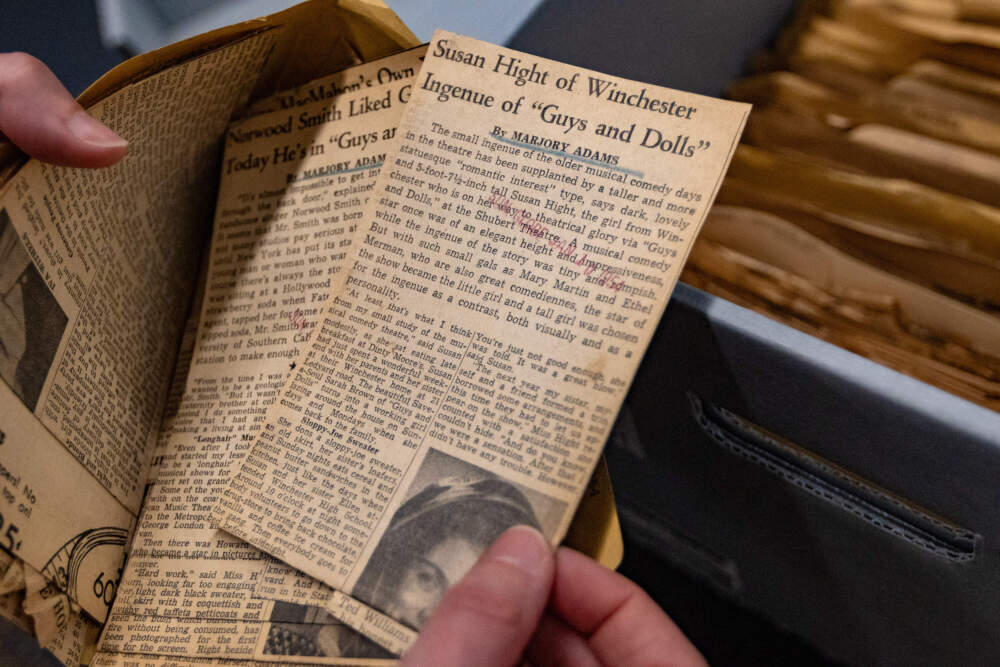

Boston’s first film critic — and likely the first in New England — was Alice Fuller Hult, who began reviewing for the Post in 1920 under the byline Prunella Hall. She lived in Brookline with her husband, a Federal Reserve banker, and appears to have used her pseudonym socially, preferring it to Mrs. Hult.

Adams was next on the beat, becoming the Globe’s first film critic in 1923 after her bosses yanked her off the overnight breaking news shift. Adams filled her Beacon Hill apartment with autographed headshots of movie stars and never regretted remaining single, although she once confessed to her sister that she sometimes got lonely on rare weekends at home.

By decade’s end, two more women had joined the Hollywood beat. Helen Eager started at the Traveler in 1927. She adored theater as much as movies, spending her weekend acting in an amateur minstrel troupe. Her office was a favorite hangout for Broadway actors visiting Boston.

During the height of Hollywood’s Golden Age, Boston’s daily newspapers employed some of the nation’s best-known film critics. All of them were women.

Elinor Hughes, meanwhile, became the film and drama critic for the Herald in 1930. She’d gone to Radcliffe and, like Eager, loved the theater, often lamenting the dwindling number of shows that came to Boston each year.

Doyle came to the Record American a few years later. Her first major Hollywood story was a series on Shirley Temple — a far cry from the gangsters she’d interviewed as a cub reporter at the Hearst papers in Chicago. She was a top-notch interviewer known for her precise shorthand and probing questions. Variety once named her “best out-of-town film critic.”

Each of the women enjoyed landing a good scoop, but they also collaborated on interviews with celebrities like Bette Davis and Clark Gable. While it’s hard to gauge the full extent of their travels, the Girls from Boston spent enough time together that they developed nicknames for each other. Hall was The First One, and Eager, The Witty One. Hughes, with her Radcliffe diploma and deep cultural knowledge, was The Intellectual One. Adams dubbed herself The Demanding One, and Doyle became known as The Sweet One for her youth and pleasant temperament.

When World War II broke out, their trips became less frequent and their numbers slowly dwindled.

The first of the "girls" to leave was Hult (aka Hall), retiring in 1941. (Her successor, Helen Popkavich, wrote under the Prunella Hall byline. It's unclear if she had any relationship with Adams and the others.) Hult died in 1947 at 51. Eager worked until she succumbed to cancer in 1952. Her death shocked her friends, who organized theater fundraisers for the American Cancer Society in her memory.

Adams, Hughes and Doyle continued working and resumed international travels after the war, sometimes joined by newer critics like Alta Maloney, who replaced Eager at the Traveler.

Hughes would have stayed on the Hollywood beat until retirement but was forced out when a new male boss took over at the Herald. She filed a union grievance and left Boston in the late 1960s to move with her husband to Long Island. She died there in 1998.

Adams served as the Globe’s film critic until 1970 and continued to file occasional columns for at least another decade.

Doyle worked longer than the others, retiring in 1973. When she died a few years later, Adams wrote a tribute that appeared in the Globe, recounting how they met on the Paramount junket and lamenting the persistent scarcity of women journalists. “She was the only one of The Girls from Boston left in the newspapers. … Others now have our jobs; they are mostly men.”

The story of the Girls from Boston is a testament to a group of women who overcame sexism and forged careers in a male-dominated industry. It’s also a cautionary tale. What I know and do not know about them is a reminder of how easily remarkable lives can dissolve into obscurity. When we overlook — or forcibly erase — women’s contributions, we lose more than individual biographies. Whole chunks of the human experience vanish. Perhaps forever.

Follow Cog on Facebook and Instagram. And sign up for our newsletter, sent on Sundays. We share stories that remind you we're all part of something bigger.