Advertisement

They said he was the Boston bomber. He wasn’t.

Editor’s note: This story mentions suicide. You can reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline toll-free by calling or texting 988.

On April 15, 2013, two men bombed the Boston Marathon. Then, they disappeared.

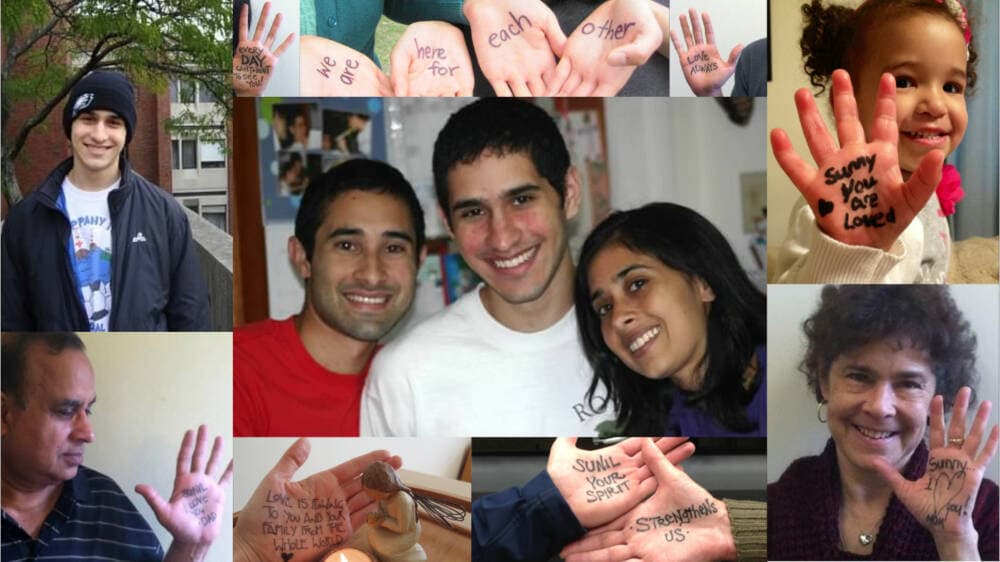

Social media users and journalists claimed that 22-year-old Brown University student Sunil Tripathi may have been one of the bombers. Some said, without hedging, that he was one of the bombers. They were wrong. He was not even a suspect.

Tripathi, who had been showing signs of depression, went missing from his Rhode Island apartment about a month before the marathon. After the online attack on Tripathi, police recovered his body. He had died by suicide.

Endless Thread co-hosts Amory Sivertson and Ben Brock Johnson revisit Tripathi's story 10 years later with his sister, Sangeeta Tripathi, and documentarian Neal Broffman.

Show Notes:

- Help Us Find Sunil Tripathi, Neal Broffman’s 2015 documentary

- "A closer look at the man wrongfully accused of being the Boston bomber" (Columbia Journalism Review)

- "#BostonBombing: The Anatomy of a Misinformation Disaster" (The Atlantic)

- "Despite what was allegedly overheard on a police scanner, Sunil Tripathi was misidentified and is innocent" (r/FindBostonBombers)

Support the show:

We love making Endless Thread, and we want to be able to keep making it far into the future. If you want that too, we would deeply appreciate your contribution to our work in any amount. Everyone who makes a monthly donation will get access to exclusive bonus content. Click here for the donation page. Thank you!

Full Transcript:

This content was originally created for audio. The transcript has been edited from our original script for clarity. Heads up that some elements (i.e. music, sound effects, tone) are harder to translate to text.

Amory Sivertson: Heads up. This episode mentions suicide. If you're having suicidal thoughts yourself and you just need someone to talk to, the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline is 988. Okay, here's the show.

Ben Brock Johnson: Amory, this episode is a long time coming.

Amory: Yeah, man. Ever since we launched the show five years ago, we have wanted to make an episode that talks about the Boston Marathon bombing. And here we are, 2023, 10 years later.

Ben: Where were you when this happened, Amory? I was not living in Boston. I was living in New York. But where were you?

Amory: I was living in Boston, and I was working on the daily local news show at WBUR called Radio Boston. And I remember the executive producer coming into the studio at 2:55 p.m. because our show went live at 3 p.m., and I'm pretty sure the first bomb went off at about 2:50 p.m. We were told to turn on the little TV in the studio, and all you saw was a cloud of smoke.

Advertisement

[(Explosion. Screaming.)]

Amory: And I remember that week we were all there, 12-plus hour days. And the interesting thing, Ben, is that the story that we're going to talk about today was not even on my radar for a long time because this story has to do with misinformation.

Ben: I think it's a good moment to reflect on this kind of manhunt that started on Reddit for the people who committed this act of terrorism. You know, when this happened 10 years ago, it felt really like a new time for the spread of information on the Internet. I think a lot of people were sort of consuming the information that they could via the Internet. And I was among those people. I was poking around, seeing what was what, and trying to figure out what was really happening. And I actually remember sort of realizing and watching a little bit of the huge kind of crowdsource effort to solve the mystery of who the suspects were. And I remember a little bit about how that all went sideways.

Amory: If you, like I, was not aware, at the time, there was a Brown University student named Sunil Tripathi who had gone missing about a month before the marathon. And on social media, people started spreading the idea that maybe this student, Sunil, was one of the Boston Marathon bombers. And they were comparing photos of him with the grainy surveillance photos of "suspect #2" that the FBI released during a press conference a few days after the bombing. Sunil was not "suspect #2." We’d learn less than 24 hours later that that was Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. But the torment this false accusation caused the family and friends of Sunil would go on to shine a light on the dangers of online vigilantism fueled by misinformation. So we talked to Neal Broffman, a filmmaker who took on that story in his 2015 documentary Help Us Find Sunil Tripathi.

Neal Broffman: Sunil was the youngest of three siblings. The Tripathi family lives outside Philadelphia. He followed in his older sister, Sangeeta, and older brother, Ravi's, footsteps to Brown University. Played saxophone and did well in school. And he was just a normal kid who was off to his university. While he was in school, he started to show signs of depression, which became more pronounced as the months went by and the years went by. And by the time of his junior year, he took a leave of absence from the university.

Ben: So Sunil went missing in March of 2013. Can you describe what was happening in his life leading up to the disappearance?

Neal: Sunil took a leave of absence his junior year and was living in an apartment in a house off campus. People, his family would go and visit him and talk to him. But he became very withdrawn and became more and more isolated until March 16th, which is the day that he went missing from his apartment. His family found out that he was missing, and they drove up to Providence and started to organize friends and schoolmates and anyone they could get to come and help them as they launched this very impressive search using social media: reaching out to the local press, leafleting, going around, visiting places, homeless shelters, talking to people all in their search for Sunil.

Amory: So there's an irony here, too, which is that Sunil himself was a really private person. But as your documentary explains, he disappears, and his family turns to social media and turns this into a very public effort. So how did they decide to take this really public approach?

Neal: I think the family did what any family would do and what any family would feel compelled to do. They're not big social media users, but this was a tool that they had at their disposal, and so they started their Facebook page, "Help Us Find Sunil Tripathi," and put up photographs and notes of encouragement and appeals to people in hopes that someone would see it in the Boston area and the greater Providence area — to try to get his name and his face in front of as many people as possible.

Ben: It's interesting to think back to that time and how different it was when people were thinking and talking about social media.

Neal: It was a very innocent time in social media, which created, you know, the foundation for what happened later.

Amory: The family's search for Sunil sounds like it was pretty relentless. Walking the Providence River, hanging up posters, just managing everything on social media. But the day of the marathon, Sunny's brother and sister took a day off from that.

Neal: They went. They had a friend who was running in the marathon. They had been looking for Sunil for almost exactly a month. He went missing on March 16th, and the marathon was April 15th. So they decided they just wanted to have a break. It was an incredibly intense emotional period of time for them. So they went to the marathon to watch their friend. And then the bombing happened.

[ABC News's George Stephanopoulos: We're interrupting your programming because there have been two explosions today at the Boston Marathon. Two explosions near the finish line just a short while ago.]

Ben: What was the seed, would you say, that would eventually kind of grow and bind Sunny's story with the Boston bombing? What was the beginning of that?

Neal: There was a young woman who went to high school with Sunil, and she saw the photograph of "suspect #2" and, I imagine, perhaps was looking at other things that people were talking about because she jumped into this conversation and said, you know, I'm a little bit freaked out right now. This, you know, suspect two looks like this kid near me who's been missing. And then that gets going and you have other people saying, you know, oh, well, Kami Mattioli said this and now you've got other people adding their thoughts to it until it comes back. And she says it was Sunil. And then it really just exploded from there.

Ben: One of the commenters at the time, you know, said — and this was a Reddit comment — "I think this is probably just the beginning of modern digital witch hunting."

Neal: Yeah, that was an incredible observation. And other people, you know, there were people who were trying to rein people in and say, Hey, hold on a minute, people are innocent here. Let's not, you know, ruin people's lives. But it just descended into the darkest, you know, places of horrible racist comments and attacks against the family. The family was receiving comments on their Facebook page and this thing just really went out of control to the point where journalists now start to pay attention.

[Hunter Walker: Hi, Sangeeta. My name is Hunter Walker. I'm a reporter with Talking Points Memo. The Boston Police Scanner has identified your brother as a potential suspect in the Boston Marathon bombing. And these reports are starting to spread.]

Ben: Yeah, it's really interesting to, as a journalist, watch this almost from the other side and witness the family receiving all of these voice messages and these phone calls. How do you think about the role of the media and your own role in telling the family's story?

Neal: When I learned about what the family had gone through, I was less surprised about the social media attacks and the comments that people were making. But I was really appalled at the behavior of the journalists. And as a journalist — I've been a journalist for 30 years — I was just disgusted with the behavior that they exhibited. And the phone calls that we hear in the film, I think are just damning.

[Katie Thompson: Hi, this is Katie Thompson with CNN. I would be so grateful for a call back.

Robin Mazzoli: This is Robin Mazzoli at Bloomberg News.

Milton Valencia: Hi, my name is Milton Valencia. I'm a reporter with the Boston Globe.

Bridget Murphy: This is Bridget Murphy. I'm calling you from the Associated Press in Boston. I'm wondering if you've heard anything new about Sunny. There's a lot of police action in the Boston area, and someone has suggested that it might be connected to your son.]

Neal: I don't believe that journalists should call families based on things that are happening on Twitter. And then it gets worse where we have Luke Russert from NBC; he talked about how this is a triumph of new media.

Neal: And then you've got reporters for Australian television going on the air saying his name.

[9News reporter: I do have some names for you. Some names to match those faces that the FBI gave us a little earlier. The first one, his name is Sunil Tripathi.]

Neal: And then when Sunil's true fate was discovered, they went back and said, Here, you remember that guy who we all said was the Boston bomber? Well, it turns out he's not. And so now he became a story, yet another cycle of Sunil Tripathi in the same mention as the Boston marathon. And so my motivation in making this film was to (1) show the consequences of unethical behavior by journalists and (2) to learn about who he really was and what this family had gone through.

Amory: About a week after the marathon bombing, Sunil's body was recovered from the Providence River. He had died by suicide.

Neal: You know, Reddit, like any other social media platform, people congregate in these chat rooms, and somebody set up the subreddit of, you know, let's find the Boston bomber. And when it started to get really big, Reddit shut the subreddit down. And my problem was, if we look at it from a sociological standpoint, people would never speak to each other the way people speak at each other in social media, especially during times of crisis. And even now, I mean, it's just so naive to say because all we have to do is look at Twitter today, and it's a cesspool of language and attack and hatred.

Ben: A family friend of the Tripathis says something along the lines of What I like about social media and what I don't like about it is that it can't be controlled. And that makes a lot of sense, but it also makes it harder to identify clear takeaways from the social media hunt for suspect two. And it probably makes it easier for social media companies to not take a certain amount of responsibility or to change policies that might help prevent something like this in the future. Do you feel like what happened to Sunny could happen on social media again, 10 years later? Is it more common now? How do you think about this now?

Neal: I think, Ben, that it absolutely could happen, and it does happen. I mean, with the murders in Idaho, there was an article I saw in The Washington Post a couple of days ago about just this thing. And so, yeah, it happens. The sad part is that I think it happens on a daily basis in lots and lots and lots of smaller ways.

Amory: You also interviewed the former general manager of Reddit, Erik Martin. Was it sort of a dance getting someone from Reddit to agree to talk to you about this, or how did that go?

Neal: Erik is a wonderful guy, and he was really broken up about what happened. He reached out to the family and apologized. He's one of the only people who apologized to the family. Someone who was in a key place, and he apologized to the family. And so we had his contact info from the Tripathi's, and we got in touch with him, and he said, sure, absolutely. I'm happy to sit down and talk. And so we went up to visit him in Brooklyn and did the interview that you see in the film.

[Erik Martin: I don't think Reddit was responsible for everything that happened, but we have a responsibility, and we, you know. Yeah, we could have, you know, maybe there were things we could have done that would have stopped or limited or changed the situation.]

Neal: And Erik spent a lot of time, I think, beating himself up about the things that he could have done. And I don't know if he ever came up with any answers.

Ben: One of the biggest things that our team discussed after our conversation with Neal was journalistic responsibility in a breaking news situation. Ultimately, our job as journalists is to find and communicate the truth responsibly and accurately, and, hopefully, kindly. And that can sometimes mean cold calls to people who are going through stuff in the hopes of finding the right facts. And sometimes that job is messy. So we wanted to acknowledge that journalists don’t always go about that job in the right way and that we should all remember the human in the work that we do.

Amory: Coming up, we talk to Sunil's older sister, Sangeeta Tripathi. We'll be right back.

[SPONSOR BREAK]

Amory: In the days after the Boston Marathon bombing, the search for the attackers was frenetic. Online, there were thousands of comments and theories. And the false accusation of Sunil Tripathi would ultimately change the online story of his life, and it would take a major toll on his family.

So, 10 years later, we reached out to Sunil's sister, Sangeeta. And she spoke with us from her home in Oakland, California.

Sangeeta Tripathi: So I grew up with my two brothers, Ravi, my middle brother, and Sunil, my baby brother, who is eight years younger than me. When we were kind of growing up, we would fall asleep watching movies lying on the carpet in our living room. And then, of course, somebody would wake up, and we'd realize that the TV was still on, and it was 2 or 3 a.m. And we would all go upstairs to bed. And he would often be the one who would wake up, and he would come over, and he'd say, Sang, it's time to go upstairs, go to sleep. And, the cranky teenager that I was, I said, Sunny, can you give me 5 minutes? Can I snooze? And he would go upstairs and do something for 5 minutes at 2 or 3 a.m. and come back down and wake me again. And just the patience and the love that existed in my little brother to do that is sort of beyond me. When I remember that, I just smile.

Amory: Oh, that's great. I guess I wonder if this time of year, every year, stirs up things for you. Obviously, we're coming up to what is the 10th anniversary of the Boston Marathon bombing and have passed the 10-year anniversary since your brother died. How are you thinking about this 10-year mark?

Sangeeta: We, every year, get together in silence and celebrate and remember my brother on the day that he went missing, which was actually, as we learned later, the day that he passed away. And this whole time, every year, it is a really somber season. We get together these days on Zoom with family and friends — what we call chosen family — and try to talk about how we're doing now and also about Sunil's life. But it's also a time where I remember his death.

Amory: I feel like when we talk about the power and potential of the Internet and of social media in particular, we hear stories usually on opposite sides of the spectrum. Like the Internet is this beautiful, vast place where we can connect and get a hundred thousand people or hundreds of thousands of people behind an initiative. But it can also be an incredibly grim and frustrating, and heartbreaking place. And I feel like this story holds both of those truths about the Internet. It makes it hard to know what conclusion to draw all of the time.

Sangeeta: Well, there are so many hard parts about the search for my brother. But one thing that I found particularly hard was walking up to strangers and, over and over, telling the story of my brother's mental health and of the search for him. And one thing that was so powerful is almost every single person, there's a silence for about 3 seconds, and then someone says, Oh my gosh, my uncle, my cousin, my wife, my neighbor also struggles. And the level of solidarity and kindness and love that was generated with strangers was just absolutely remarkable and tragic. Also, to think of how many people are affected by mental health. When you're on the Internet, the interactions are a little bit different. People are touched, people are affected. But again, you're still strangers in this other way. And I think, as you mentioned, that can be both very powerful and can also be very dangerous.

Amory: Do you remember how you first found out that Sunil had been named incorrectly as potentially one of the suspects that the FBI were looking for with regards to the Boston Marathon bombing?

Sangeeta: Yeah. As you know, we had this very active Facebook page that the purpose of it was to get people to see Sunil's photo and to share any information if they'd seen him. And we started getting some posts on our Facebook feed that were funny and confusing, and we didn't really have context. And then we started going on the Internet and googling — like, What's happening? — just like everyone else. And we ran into the Reddit mess that was emerging that night. And so we knew at that point that something was going on. We didn't really realize the magnitude of what was going on until I received, gosh, over 75 calls from media throughout that night of people who started very gently saying, Oh, Sunil is a person of interest to Oh, Sunil is, you know, involved in the horrible tragedy that happened.

Amory: How did your family spring into action when you start seeing these comments? Or was there a conversation kind of like, all right, this is happening. What do we do? How do we get through this as a family?

Sangeeta: The thing that was on all of our minds is, you know, what is the impact of on Sunil? We still were hoping that he was alive and that he was somewhere and that he might even be hearing these awful things about him, already not being in a good state. So we worked together, we made some quick decisions, and then the next morning, things had blown over in the sense that the correct person was identified. And that was a really hard moment for our family to decide. What are we going to do next? And at that point, my brother and I — my living brother, Ravi, and I — were very clear that we have to go back to that same media that was saying awful things in the middle of the night and ask them for interviews and get on those shows and talk about our brother who is still missing. And I remember that being a really tough moment to realize the same people, the same systems that can be quite dangerous are the systems that we're reliant on to look for our brother. And so that was a very fast and difficult turnaround for us.

Amory: Were there ever any physical threats of harm or intimidation moves made against your family by any of the commenters on social media that you were seeing?

Sangeeta: Claiming that my brother was involved is actually a threat of harm — is harm — because of my brother's mental state. And I'm so glad in certain ways that my brother was not alive because I don't know what the impact on him would have been.

Amory: I feel like there could be many takeaways from all of this. And there are some that are takeaways specifically for people who might feel tempted to, you know, post things on social media. And there are also takeaways for journalists. And I wonder what those are for you.

Sangeeta: The thing that made me so upset and heartbroken hearing journalists jump onto the bandwagon of social media is I was very naive in thinking that there was a firewall between somebody in a hoodie, you know, who's blogging on social media and a professional journalist. And what I found was that there wasn't. And so I think that there should be a much higher bar of research and professionalism around what is shared in a journalistic space and that journalists have an incredible amount of power in terms of what they communicate. And the pressure to get the story can be very, very harmful if not taken seriously. For social media, for all of us, for everyone who's on the Internet, I think my biggest takeaway is, How do we use the Internet for good, for connection, for support, for meaning, without forgetting that there's another human being on the other side of that chat? So my dream is that somehow there would be a button before you could click "send" that says, "Hello, there's a person on the other end of the line. Is this something you would say to your friend face-to-face?" But, of course, that's not the nature of social media.

Amory: Has this experience really changed your approach to social media?

Sangeeta: I was not a big social media person before the search for my brother and definitely was not after. I am very tender and aware of the power, both for good and for incredible harm.

Amory: Yeah. Ten years later, how are you doing? How is the rest of your family doing?

Sangeeta: As everybody who's lost somebody knows, there are holes that are in our hearts and our spirits that never get healed. Time passes, and new things happen. But my entire family and I still have a big Sunil-shaped hole in our hearts. The fact that he died by suicide, the fact that there was so much tragedy at the end of his life in some ways makes it even more sad. But we carry, I carry, his loss in my life constantly. I have a young child now and think constantly about that he'll never know his Uncle Sunil and that there's so much life that [my brother] didn't get to live. Part of why we continue to speak out as a family is to use the painful and hard story of my brother's life to normalize and to talk about mental health so that other families ideally can get the support they need and other kids can live.

Amory: Sangeeta, thank you so much for taking time to share more about your brother.

Sangeeta: You're welcome.

Amory: We invited someone from Reddit to join us for this episode since Erik Martin, whom we heard from in Neal's documentary, is no longer with Reddit. Reddit declined to make anyone available to talk to us but said in a statement: "Reddit's sitewide policies strictly prohibit posting someone's personal information, including for the purpose of harassment or vigilantism." They also told us doxxing and witch-hunting are against their sitewide policies. But it's an open invitation, Reddit.

Ben: Endless Thread is a production of WBUR in Boston.

Amory: This episode was produced by Dean Russell.

Ben: It was co-hosted by me, Ben Brock Johnson, and...

Amory: Amory Sivertson.

Ben: Mix and sound design by Emily Jankowski. The rest of our team is Quincy Walters, Grace Tatter, Nora Sacks, Paul Vaitkus, and Matt Reid. We'll talk to you next week.

Editor’s note: You can call or text the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline toll-free at 988.