Advertisement

What Forgiveness Means Nearly 5 Years After Emanuel AME Church Mass Shooting

Resume

In 2015, a white supremacist walked into a Bible study and killed nine black churchgoers at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

Nearly half a decade later, hate crimes are on the rise across the country — and South Carolina is one of only four states without any hate crime legislation. Democratic state Rep. Beth Bernstein is the latest lawmaker to try enacting a hate crime bill.

The shooter, Dylann Roof, was sentenced to death on 33 counts of federal hate crimes. But Bernstein wants to enact legislation that would punish people at the state level for any type of crime motivated by hate based on someone’s religion, race, gender or sexual orientation.

As the only woman of Jewish faith in the South Carolina legislature, Bernstein says this bill is also personal. She says it’s important for the state to recognize and stand up against this “horrible behavior.”

“In this time that we're experiencing, there's an uptick in anti-Semitic events all across this nation. There is an uptick of all sorts of racially motivated violence,” she says. “And I think this is the time that we need to stand up and say, ‘This is wrong and we're not going to tolerate it.’ ”

Bernstein’s hate crime bill is now making its way through the legislature. She anticipates an “uphill battle” but continues to put pressure on members of law enforcement and the business community who think it isn’t the right time for hate crime legislation.

“I would refute that and say the time is absolutely now,” she says.

Democratic Rep. Wendell Gilliard has also pushed for hate crime legislation over the past several years. His measure would have made it a felony to commit an offense with the intent to intimidate, assault or threaten a person based on an identity such as race or religion.

But Gilliard's bill, along with several other variations from other lawmakers, have died in the legislature.

Republican Sen. Greg Hembree is one of the lawmakers who oppose the idea. He thinks while this legislation is meant to protect certain people, hate crime laws discriminate against others.

“Saying that because of the color of your skin or because of your gender or because of your religious beliefs, your rights as a victim are superior to other people's rights is problematic,” he says.

Though FBI data show hate crimes against marginalized people reached a 16-year high in 2018, Hembree thinks the laws are symbolic and do not deter people from committing crimes. He says he believes hate crime laws are “feel-good legislation” that wouldn’t be enforced because it’s “virtually impossible” to prove the mindset of a defendant in a trial.

But for the Emanuel church congregation, Rev. Eric S.C. Manning says a hate crime law is about acknowledgment.

“It's not necessarily a feel-good type of legislation,” he says. “It is just something to say, ‘I hear your pain, I understand your struggle. And though I can't necessarily undo what was done, I'm going to add my voice to say never again — not now, not ever.’ ”

Emanuel is now part shrine, part tourist attraction. A sophisticated security system keeps visitors from easily entering, with cameras surveilling the over 200-year-old church. Manning says church leadership is still learning how to ensure worshippers are protected but don’t have to think about security or cameras.

People outside the congregation will gather in front of the church to pray and pay their respects — like Regena Thomas, who traveled to Charleston from New Jersey for this week’s Democratic debate. She’s visited the church nine times over the past five years.

Thomas says she’s been thinking about how lawmakers will stand up against hate and how to take a lesson in compassion from the congregation. She struggles with whether she could learn to be as forgiving if the tragedy happened to her.

“Some of my pain is 'God, I want to get there … ' ” she says. "This congregation lived what they learned — totally biblical.”

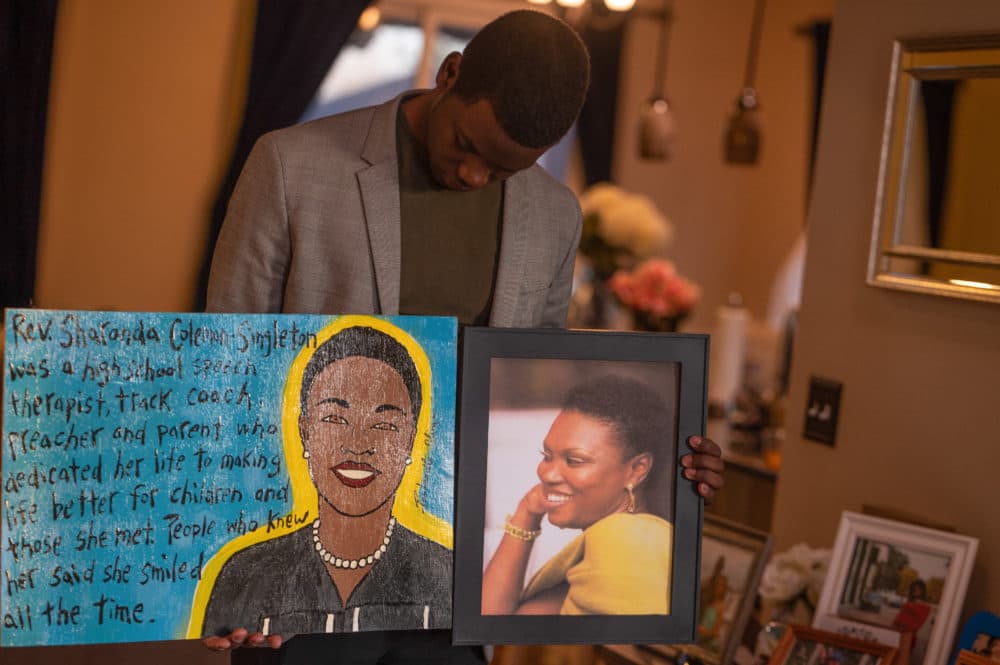

The church and grieving family members like 23-year-old inspirational speaker Chris Singleton seek to heal through the radical act of forgiveness. Chris Singleton lost his mother — Sharonda Coleman Singleton — in the shooting.

At age 18, the new-found responsibility of caring for his younger siblings transformed him from child to adult in an instant. Though his mother didn’t live to see him become a father and husband, the practice of forgiveness rooted in his faith keeps him going.

He recalls a “powerful” quote he read from Christian author Lewis B. Smedes: “To forgive is to set a prisoner free and discover that the prisoner was you.”

“I believe so many people view forgiveness as letting the other person off the hook,” he says. “We think that we're letting the other person off the hook by forgiving when in actuality we're just freeing ourself from that constant feeling of revenge.”

Another quote he often thinks about is one his mother used to say: “Love is stronger than hate.” Chris Singleton believes South Carolina will one day join the 46 other states with hate crime laws on the books.

On top of believing in forgiveness, Singleton preaches the importance of another useful virtue — patience.

“As a state, we are behind in some things, but I think we're trying to move forward and it may take time,” he says. “I've realized that. I'm a young guy, but I realize some things do take time.”

Cristina Kim produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Kathleen McKenna. Allison Hagan adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on February 27, 2020.