Advertisement

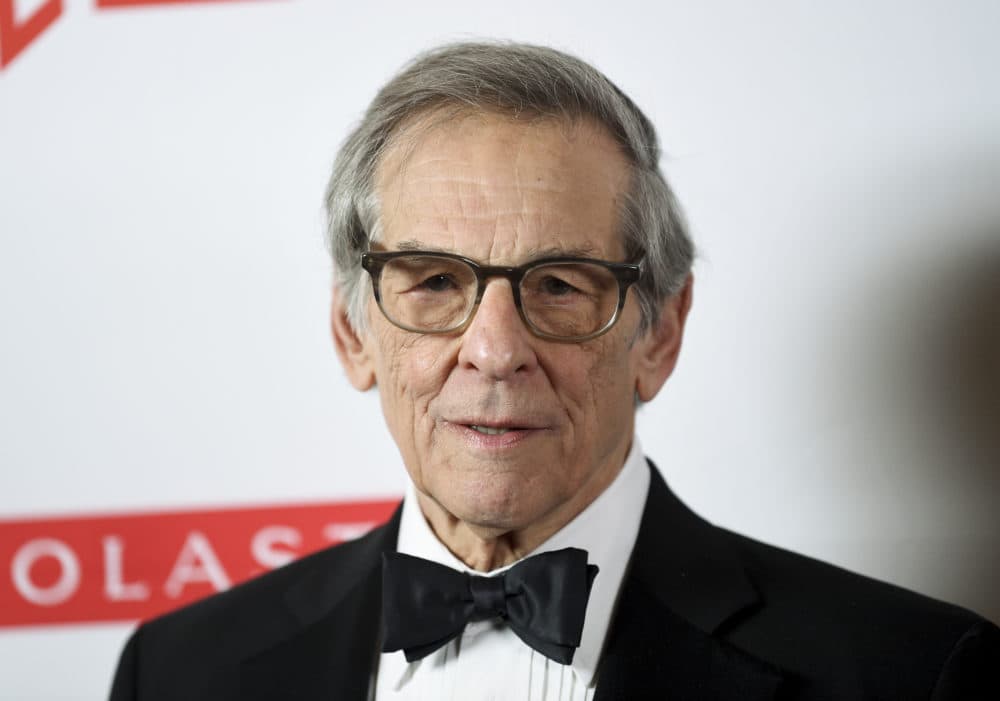

Biographer Robert Caro Says To Understand Political Power, Listen To The People It Impacts

Look closely at the books in the background of a Zoom call and you might see one or two written by two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author Robert Caro.

When his research partner and wife, Ina Caro, noticed his book "The Power Broker" sitting behind people's heads, Robert Caro says he was startled and humbled.

“I'm feeling good about it because that book came out 46 years ago,” he says. “To see young political reporters using it now, that's sort of, to be honest with you, thrilling to me.”

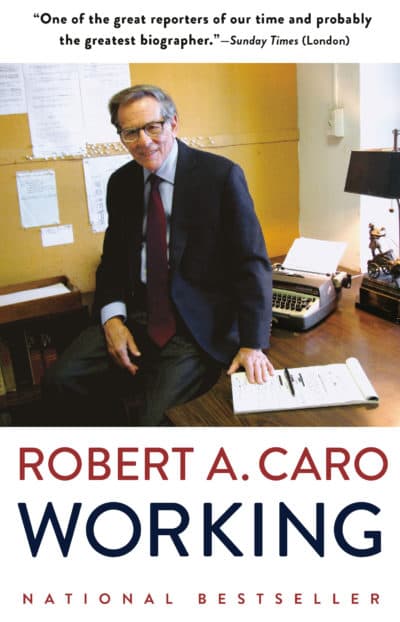

His latest book "Working" isn't really a memoir — it's about the processes behind Robert Caro's research and interviews as he writes his acclaimed books, such as"The Power Broker" and "The Years of Lyndon Johnson."

He spent years on each — tracking down families carelessly displaced by Robert Moses’ highways and moved his family to Texas to understand former President Lyndon Johnson’s upbringing.

"The Power Broker" tells the story of brilliant but flawed New York builder Robert Moses, who built bridges, parks and Jones Beach on Long Island over many years. While Robert Caro worked on the book, Ina Caro sold their house to acquire some extra money.

Despite their tough financial situation, Robert Caro felt he needed to finish the book to help people understand how power works.

“Robert Moses was never elected to anything. He held power for 44 years. How did he get that?” he says. “I felt it was important to finish the book so that even if I never got to do another one, people would understand how power really works in cities.”

As a young reporter working at Long Island’s Newsday paper, he received a call from someone at the Federal Aviation Administration offering him files related to a controversy over building an airport. While his colleagues spent their Sunday at a picnic on Fire Island, he sorted through the files.

He returned home to a voicemail from the managing editor’s secretary, which prompted him to tell his wife that the “old-time newspaperman” planned to fire him. Instead, editor Alan Hathway gave him the job of investigative reporter along with a piece of memorable advice.

“He said, ‘Just remember one thing: Turn every page.’ ” he says. “And I remember that and sort of tried to follow it all my life.”

Later, he found more papers related to Moses tucked inside a huge building in New York. These files uncovered a deal to move a road from passing through a rich man’s private golf course to farmland four miles away.

Robert Caro found the farmers impacted by this move — and he described the experience as “a moment of awakening.”

Advertisement

“It was the moment that I realized that if I really wanted to write about political power, I would have to write not only about the men who wielded power, who had power,” he says. “I would have to write also about the powerless, the people who didn't have power and whose lives were affected either for good or for ill.”

He came to this conclusion after interviewing the son and wife of a farmer who had died.

“They said, ‘The day Robert Moses took our farm was the day our lives were ruined,’ ” he says. “When you heard that, you suddenly said that's an aspect of power, too: what government can do for people and what it does to people.”

While reporting on former President Johnson, Robert and Ina Caro moved from New York to Hill County, Texas, in Johnson’s home state. Without running water or electricity, residents got their water from a 75-foot-deep well.

One elderly woman grabbed a water bucket with a rope from her garage and took him to the well. Pushing the boards covering the well aside, she dropped the bucket in the water and told him to pull it up.

The woman told him to put a bar of wood over his shoulders like cows wear to carry the bucket — and both were heavy.

Coming from New York, he noticed the women in Hill County seemed more “stooped” than women he knew in the city. The women used the expression “bent” to describe the impact of carrying water from the well on their posture.

“This one woman said to me, ‘I swore I wasn't going to be bent like my mother. But as soon as my kids started to come and I had to carry the water, I knew I would look exactly like my mother looked,’ ” he recalls.

Johnson was a “political genius,” Caro says. While running for Congress, Johnson used the experiences of these women in what Caro calls his “magic line.”

“If we get electricity here, you won't look like your mother,” Johnson said.

But at the time, this mission seemed impossible without a dam or a source of water power. Even with a dam, thousands of miles of lines were needed to connect the scattered farms — but Johnson persuaded former President Franklin D. Roosevelt to make it happen.

As he works on his fifth and last book about Johnson, Caro is looking at a less triumphant part of the former president’s legacy, the Vietnam War. Caro says when he thinks about the powerful men he writes about, sometimes he wants to cry.

Despite the dark last chapter of his political career, “Johnson had a compassion for people and a genius for turning that compassion into government action,” Caro says.

Four days after the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, Johnson had to make his first speech to Congress. His aides and speechwriters urged him not to make civil rights a priority in fear of antagonizing the Southerners in control of Congress, Caro says.

In his first presidential speech, right in front of a row of Southern senators, Johnson said his first priority was to pass Kennedy’s civil rights bill.

“His fight for civil rights and voting rights is epic,” Caro says. “It's an epic triumph of what government can do, just as in Vietnam is an epic — an epic of tragedy.”

More From The Interview

On writing “SU” over and over in his notes

“It means shut up. I talk too much. So I learned that if you could just not talk, you ask a question, the guy doesn’t want to answer. One of the best things I found that I can do is not say the next line. You know, there's a silence and we're all human. We feel we want to fill it up. But if you don't fill up more often, they'll fill it up and they'll fill it up with something they wouldn't otherwise have said. So, yeah, if you look through my notebooks, you'd see an awful lot of SUs written.”

Alex Ashlock produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Peter O'Dowd. Allison Hagan adapted it for the web.

Book Excerpt: 'Working'

By Robert Caro

“Turn Every Page”

People are always asking me why I chose Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson to write about. Well, I must say I never thought of my books as the stories of Moses or Johnson. I never had the slightest interest in writing the life of a great man. From the very start I thought of writing biographies as a means of illuminating the times of the men I was writing about and the great forces that molded those times—particularly the force that is political power.

Why political power? Because political power shapes all of our lives. It shapes your life in little ways that you might not even think about. For example, when you’re driv¬ing up to the Triborough (now Robert F. Kennedy) Bridge in Manhattan in New York, you may notice that the bridge comes down across the East River in Queens opposite 100th Street. So why do you have to drive all the way up from 100th Street to 125th Street to cross it, and then basically drive back, which adds almost three totally unnecessary miles to every journey across the bridge.

Well, the reason is political power. In 1934, Robert Moses was trying to get the Triborough Bridge built, and he couldn’t because there wasn’t enough public or political support for the project. William Randolph Hearst, the publisher of three influential newspapers in New York, owned a block of tenements on 125th Street. Before the Depression, the tenements had been profitable, but now poor people didn’t have jobs, and couldn’t pay their rent. Hearst was losing money on the buildings and he wanted the city to take them off his hands by condemning them for some project. Robert Moses saw that the project could be the Triborough Bridge, and that’s why the bridge entrance is at 125th Street. That’s a small way in which political power affects your life. But there are larger ways, too.

Every time a young man or woman goes to college on a federal education bill passed by Lyndon Johnson, that’s political power. Every time an elderly man or woman, or an impoverished man or woman of any age, gets a doctor’s bill or a hospital bill and sees that it’s been paid by Medicare or Medicaid, that’s political power. Every time a black man or woman is able to walk into a voting booth in the South because of Lyndon Johnson’s Voting Rights Act, that’s political power. And so, unfortunately, is a young man—58,000 young American men—dying a needless death in Vietnam. That’s political power. It affects your life in all sorts of ways. My books are an attempt to analyze and explain that power.

When did I start writing? It seems to me that I always wrote. I went to elementary school at Public School 93 in Manhattan. It was on 93rd Street and Amsterdam Avenue. It had never had a school newspaper, so when I was in the sixth grade I created one. We mimeographed it. I remember I couldn’t get the ink off my hands—I showed up in class with ink all over them.

My mother died when I was eleven, and before she died she told my father that she wanted him to send me to the Horace Mann School. I began there in the seventh grade, and almost immediately I began working on the school newspaper. The paper meant something special. I don’t think we were even conscious of what, but we knew. To this day, I have dinner fairly regularly with guys who worked with me on the Horace Mann Record.

I always liked finding out how things work and trying to explain them to people. It was a vague, inchoate feeling—I don’t think of it in terms of, Why do I want to be a reporter? At Princeton, I was the paper’s sportswriter and I had a column, but I found myself writing more about the coach and about how he coached than about how the team was actually doing. I think figuring things out and trying to explain them was always a part of it.

My first job out of Princeton, in 1957, was for a newspaper in New Jersey—the New Brunswick Daily Home News, “The Voice of the Raritan Valley”—that was very closely tied to the Democratic political machine in New Brunswick. In fact, it was so closely tied to the machine that its chief political reporter, who was so elderly that he had actually covered the Lindbergh kidnapping in the early Thirties, would be given a leave of absence during the political campaign—that’s the chief political reporter—so that he could write speeches for the Democratic organization. This reporter suffered a minor heart attack shortly after I got there, so someone else was going to have to write the speeches, and he wanted it to be someone who would pose no threat to his getting the job back later, so he picked this kid from Princeton, and I found myself working for the political boss of New Brunswick, this tough old guy.

For some reason, he took a shine to me. My salary at the paper was fifty-two dollars a week. No specific salary was mentioned when I went to work for him, but every time he liked a speech I wrote he would pull out a wad of fifty-dollar bills and hundred-dollar bills and peel off what seemed like quite a few and give them to me. I was happy with that aspect of the job, but then came Election Day.

He brought me along to ride the polls with him, which meant going from polling place to polling place to make sure that everything was proceeding as it should. But on this particular day the driver of his limousine wasn’t the regular driver. The driver had been replaced by a police captain.

I didn’t understand why, but as we got to each polling place a policeman would come over to the car, and the captain and my employer would roll down their windows, and the boss would ask how things were going. Usually the answer was everything is “under control.” But at one polling place, the policeman said they had had some trouble, but they were taking care of it. And then I saw that there was a group of African-American demonstrators, neatly dressed men and women, mostly young, who had obviously been protesting something that was going on at the polls. And as I watched, police paddy wagons pulled up. There was one there already. And the police were herding the protesters into the paddy wagons, nudging them along with their nightsticks.

The thing that got me when I thought about this in later years—what it was that really hit me—was the meekness of these people; their acceptance, as if this was the sort of thing they expected, that happened to them all the time. All of a sudden I didn’t want to be in that big car with the boss. I just wanted to get out.

As I remember it, I didn’t say a word. The next time we pulled up to a traffic light, I just opened the door and got out. The boss didn’t say a word to me. I think he must have understood. Anyway, I never heard from him again.

But I had realized that I—Bob Caro—wanted to be out there with the protesters.

Not long after that, I decided that if I wanted to keep on being a reporter, I needed—for myself—to work for a paper that fought for things. Why? I couldn’t explain it then, and I can’t explain it now. But it had to do with that Election Day. With the protesters. With the cops nudging them along with the nightsticks. I had gotten so angry!

So I looked around for a newspaper that fought for causes. There were several at the time, and I wrote letters to all of them asking for a job. It took a while, but I got an offer from Newsday on Long Island—a real crusading paper then—and in 1959 I went to work for them.

Excerpted from "Working" by Robert Caro. Copyright © 2019 by Robert Caro. Republished with permission of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

This segment aired on June 24, 2020.