When Inmates Die Of Poor Medical Care, Jails Often Keep It Secret

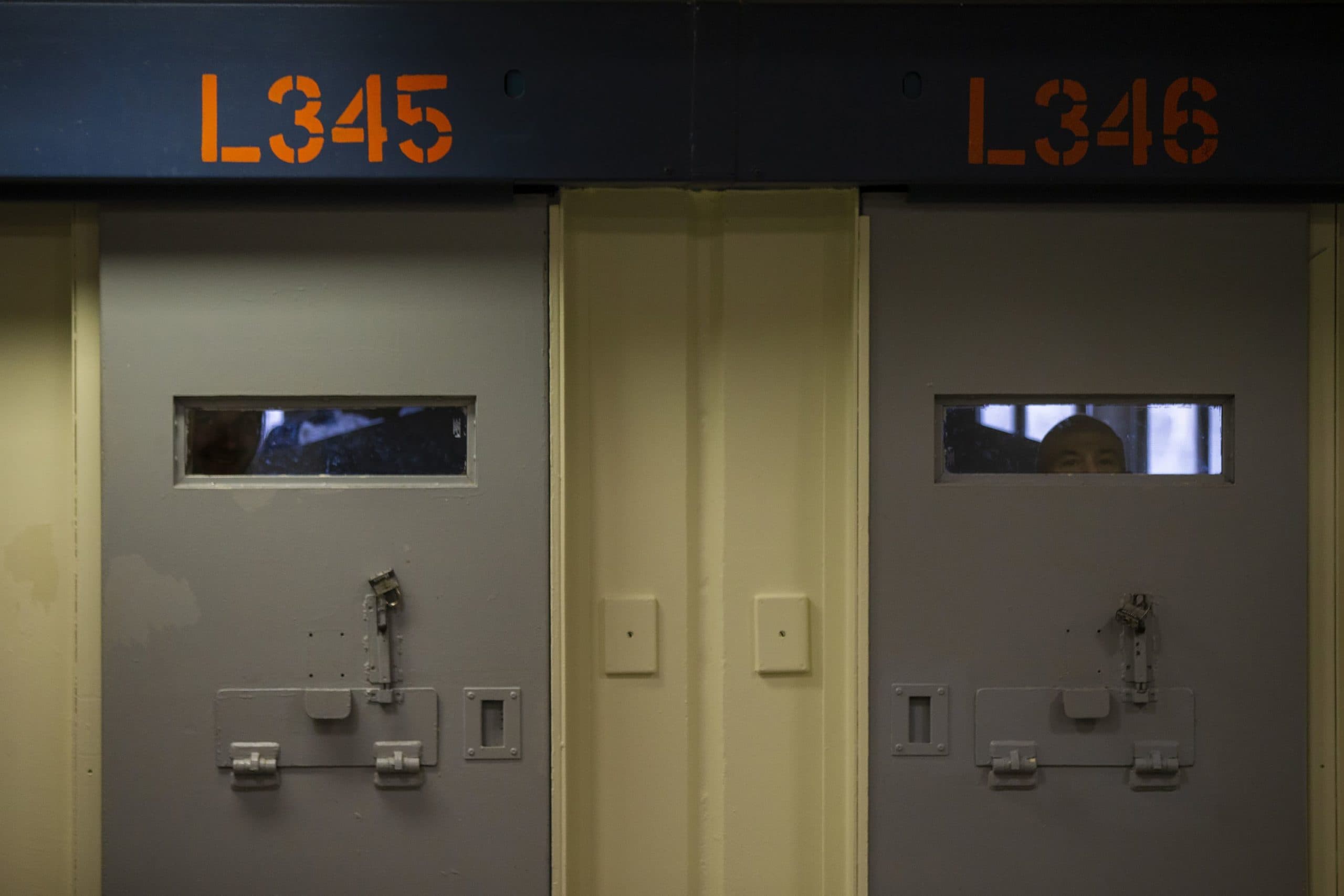

Confined at the Worcester County jail in 2016, Michael Ramey was in agony. At various times, he couldn’t walk, see or hear.

As he awaited trial, he complained to medical staff of his worsening symptoms, jail records show. He told a nurse, “my head was about to explode.”

But hardly anyone believed him. Within a month, Ramey died of a treatable type of meningitis. He was 36.

A Worcester County jail report would say he died of “natural causes.”

A WBUR investigation found that when people suffered from dire medical conditions in Massachusetts county jails, they were often ignored or mistrusted, with fatal consequences. The sheriffs and for-profit companies increasingly responsible for inmate health care face little oversight, and often have withheld the circumstances of these deaths from the public — even from inmates’ families.

Ramey’s death and others in county jails came well before the coronavirus began to raise global health alarms. Now, as the pandemic upends life as we know it, reaching into every corner of society, this vulnerable group behind bars is at risk of falling ill, out of the public eye and at the mercy of a system that has failed many before.

“Jails are perhaps the least accountable part of government in the United States,” said David Fathi, director of the ACLU National Prison Project. “When you combine that lack of transparency — that lack of oversight — with a marginalized, unpopular captive population, it's a recipe for neglect and mistreatment.”

Reporters set out to uncover how many people had died in Massachusetts jails over the past decade, who they were, and what killed them. The information available to the public was extremely limited.

Data compiled by WBUR show that 195 people died in the custody of sheriffs from 2008 to 2018. Of those, 127 died of medical causes such as heart disease, sepsis or drug overdoses. Most of the rest died by suicide. One woman lost a late pregnancy.

Of the cases reporters were able to identify and examine closely, at least one-third had allegations or evidence of poor medical care before their deaths, based on lawsuits, internal jail investigations, state police records and interviews.

Now, under the coronavirus threat, medical care in jails — where most people are awaiting trial — is sure to be tested. As of Monday, at least 79 people incarcerated or working in jails or prisons in 16 states had tested positive for the coronavirus, including at least seven in Massachusetts.

Before the outbreak, WBUR made an independent accounting of Massachusetts jail deaths. That examination also found that the Department of Justice’s tally of deaths in custody is inaccurate and does not represent the full breadth of lives lost. In the latest nine-year period available, Massachusetts sheriffs reported to the DOJ that 125 people died from all causes. But WBUR found 37 more deaths.

In jails large and small, there were cases of inmates being denied prompt care. Some were not believed when they called for help, and others were simply ignored in the custody of sheriffs who have a legal obligation to care for them.

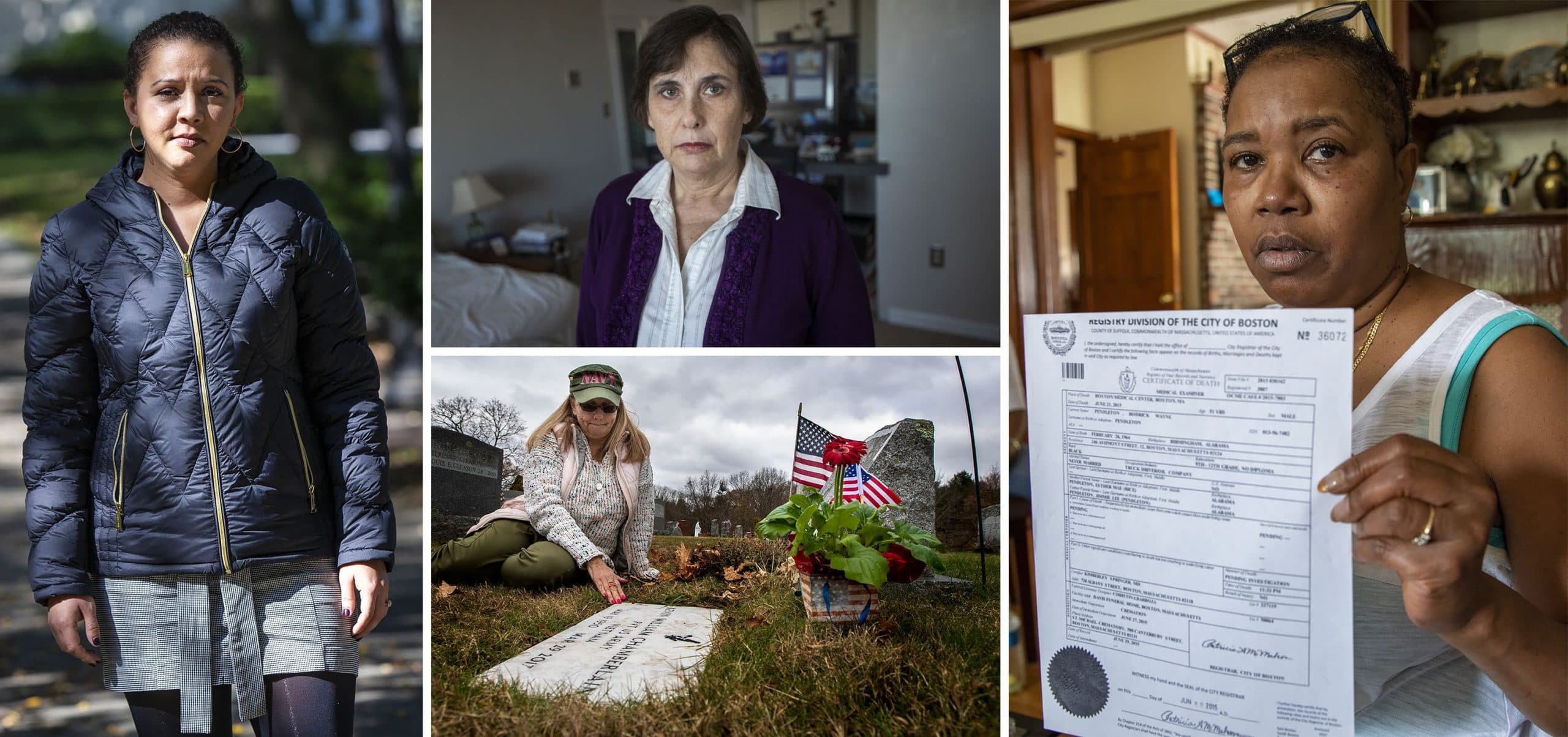

Susan Chamberlain lost her husband. Tony Dunn lost his son. Abigale Mulstay lost her sister. Judith Tavarez lost her father. All still have questions about how their loved ones died.

On any given day in the commonwealth, there are about 9,500 people held in 13 county jails, more than in the state’s prisons. A majority of those people, 65%, have not been convicted of a crime, sheriffs say. The rest are serving sentences of less than two-and-a-half years.

“A lot of people coming into jails ... are not necessarily hardened criminals,” said Andrew Harris, professor of criminology and justice studies at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell. “And in many, many cases they're there because they can't make bail.”

Jails are operated by elected sheriffs and funded by state taxpayers. Under the U.S. Constitution, jails are required to provide health care comparable to what people receive in the community. But that’s not always how it works.

“All too often,” Fathi said, “jail health care is vastly inferior, in some cases virtually nonexistent.”

At the Suffolk County House of Correction, a man complaining of stomach pain for days wasn’t sent to the hospital in time; he died of a bowel obstruction. In the back of an Essex County sheriff’s van for six hours, an inmate died of an overdose, as guards sat in the front seat. In the Bristol County jail, a woman died of a heart infection in a hallway, waiting for a ride to the infirmary.

Certainly some who had medical problems would have died regardless of whether they were incarcerated. Many struggle with mental illness and drug addiction. These can also be factors in suicides, which account for one-third of the Massachusetts jail deaths that WBUR reviewed.

People who died in jail frequently did so within days or weeks of arriving. A WBUR analysis shows that nearly half the deaths occurred in the first month of incarceration.

'Everybody Writes It Off'

Michael Ramey’s older sister, Kerri Joyce, saw him at Christmas before he died, in 2015. She bought him a few sweatshirts and hoped he’d stay sober this time.

They grew up in Randolph. Ramey’s sister said he was smart, funny and sweet. College wasn’t for him as he wanted to work with his hands, like his relatives with union jobs. In his 20s, he was prescribed pain medication for a skull fracture and became addicted.

In July 2016, Ramey was booked at the decrepit Worcester County jail, awaiting trial for unarmed robbery. His intake form and medical records showed he had hepatitis C, epilepsy, anxiety and a history of drug use.

Within days, medical records show, Ramey started to complain about headaches. Over the next month, his speech was slurred, and he had paralysis on his left side.

On Aug. 13, jail medical staff sent him to Saint Vincent Hospital. A doctor diagnosed Ramey with atypical migraines, and said he needed to see a neurologist within a week.

But the guards returned Ramey to his cell, and staff never set up that appointment, according to the family’s lawsuit. About 10 days later, Ramey fell down for the first of several times, medical records show.

The medical staff suspected he was lying about his symptoms to get drugs.

A nurse practitioner wrote in Ramey’s record that he was showing “apparent medication seeking behavior.” After a body-strength test, she stated he “does not appear to be using full effort.”

Ramey fell again the next day. Crying, he explained he couldn’t feel his left leg. The jail physician also wrote that Ramey was showing “med seeking behavior.”

The family’s attorney, Hector Pineiro, said in an interview, “Even though this kid is screaming that he has a neurological condition that's raging, everybody writes it off.”

On Aug. 30, records show Ramey complained of headaches, left-side pain and dizziness. He fell face-down on the floor, in front of the staff.

WBUR asked Dr. Matthew Tobey, a physician with Massachusetts General Hospital who has experience working in jails, to review the case. He said, “It is surprising and troubling that the jail’s medical staff did not recognize worsening meningitis.”

Over the next several days, Ramey’s symptoms waxed and waned. Sometimes he refused to have his vital signs taken. He asked for the anti-seizure medication the hospital physician had prescribed but the jail had stopped giving him.

By Sept. 7, a licensed practical nurse found Ramey on the floor of his cell, unable to walk to the door.

Ramey’s medical records said, “He was repeatedly shouting, ‘What, I can’t hear you. I can’t hear or see anything … I need help, something is wrong.’ ”

The medical staff sent Ramey back to Saint Vincent Hospital. Eight days later, a standard test showed he had cryptococcal meningitis, which the lawsuit claims should’ve been detected by medical staff.

“Nobody thought he was being truthful,” Ramey’s sister, Joyce, said. “I can’t believe how sick he was, and the reaction he got from the medical professionals.”

WBUR found numerous cases in the state where jail and medical staff assumed inmates were lying about their symptoms — “malingering,” as they call it in jail. But reflexively disbelieving inmates can lead to medical conditions growing more serious, and even to death.

“There is a baked-in cynicism about what inmates say and what they complain about,” Harris, the UMass professor, said. “It's just part of the correctional culture. The risk is that you assume that everybody is lying to you.”

The Ramey family is suing the Worcester County sheriff’s staff and the health care provider, Wellpath Holdings Inc., of Nashville, Tenn., as well as Saint Vincent Hospital.

Spokespersons for Wellpath and the hospital declined to comment on Ramey. In an interview, Wellpath President Kip Hallman said jails are challenging clinical environments, and that patients often are in poor health and haven't seen doctors outside of jail in a long time. (Wellpath is a financial underwriter for WBUR. It has no editorial involvement in this story.)

Feds Investigated Worcester

The Worcester County jail came under rare federal scrutiny in 2007, when the DOJ investigated the facility after what it called an “alarming” number of suicides.

The resulting 2008 report cited massive overcrowding, brutality by guards, overuse of restraints and segregation, and a failure to properly assess inmates’ mental health upon arrival.

The DOJ questioned the jail’s ability “to keep its inmates safe” and made numerous recommendations. But the report said even federal officials could not get a complete read on Worcester: “The Jail has repeatedly refused to give our expert consultants access to the facility’s mortality reviews,” citing attorney-client privilege. “Consequently, we are unable to determine whether the Jail is conducting a meaningful analysis of its in-custody deaths.”

Mortality reviews are reports that sheriffs, with the help of medical staff, must complete within 30 days of a death under state Department of Correction rules. They’re meant to summarize the circumstances of each death, and to report any necessary improvements in care or procedures. But the mortality reviews WBUR was able to obtain hid key elements from the public.

For example, the Worcester sheriff’s report on Ramey states: “Pursuant to policy, the mortality review will seek to determine” — but the next three pages were blacked out.

The reports are “all self-congratulatory” and often blame the inmate's death on a “bad lifestyle,” said Pineiro, Ramey’s attorney, who has seen several of these reviews.

The for-profit medical providers hired at many jails add a layer of secrecy. They aren’t subject to public records laws as sheriffs are, nor do they have to offer information to grieving families.

In the wake of the DOJ report, Worcester County Sheriff Lewis Evangelidis, a former state lawmaker elected sheriff in 2010, made some changes. He hired an outside firm to take over health care: NaphCare Inc., which was later replaced by Wellpath.

Since the DOJ investigation, 29 more people have died in the Worcester County sheriff’s custody. Ten were suicides; the rest resulted from a variety of medical issues. Evangelidis declined to be interviewed.

Jail Superintendent David Tuttle would not discuss the Ramey case, but said in an interview that many of the people who’ve died in Worcester had serious medical issues when they arrived.

“We don't want it to happen, but it's not by any neglect of ours,” Tuttle said.

Weak Oversight Of Deaths Reported To DOJ

The federal Death in Custody Reporting Act requires the government to collect data on the more than 1,000 inmates who die every year in American jails. Sheriffs have been required to file a form called a CJ-9, which provides the inmate’s name, age, race, cause of death and other information.

But compliance by the roughly 3,000 U.S. jails has been voluntary. The DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, which for years has compiled the data, has no enforcement teeth. The result is that an unknown number of deaths go uncounted, and since 2014, reports have been years late.

A bureau spokeswoman in an email blamed the delay on the complexity of gathering the data, and on waiting for medical examiners’ reports.

As to the discrepancy between the DOJ’s death count and the 37 more deaths discovered by WBUR, Ann Carson, acting chief of the bureau’s corrections unit, said, “We report what is reported to us, and we trust our respondents."

Share your story or send our investigative team a tip. Plus, sign up to get WBUR investigations in your inbox. And listen to this series on your smart speaker.

A new system launched this year will be even less transparent. Another arm of the DOJ will rely on states to collect death data. In Massachusetts, a unit of the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security is assuming this role. It will take information from the state’s medical examiner — instead of directly from sheriffs, a spokesman said.

WBUR found Massachusetts sheriffs largely unaware of the change, raising questions about how thorough the death count will be nationwide. When asked for a list of jail deaths under the new system, the state did not provide the records.

“The quality of your data is going to diminish,” with the reporting change, said Nancy Neveloff Dubler, professor emerita at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York and a specialist in the ethics of jail health care. “It’s about to get worse, and less reliable.”

To create an accounting of deaths, WBUR sought public records from the 13 sheriffs who run county jails in the commonwealth. The information they provided varied widely.

Sheriffs in five large counties — Essex, Middlesex, Worcester, Norfolk and Hampden — all refused to disclose the identities of the dead, citing medical privacy or potential litigation.

Sheriffs' internal investigations of the 127 deaths due to medical reasons sometimes didn’t include key interviews with witnesses or guards, or video went missing.

"... many of these deaths, in fact, reflect conditions that the person was exposed to behind bars.”

Dr. Homer Venters

It’s unclear whether corrections officers or medical staff faced repercussions in the wake of these deaths and internal investigations. Officials at the Suffolk and Worcester County jails said they could not recall anyone being punished.

Disciplinary records for jail employees are not considered public in Massachusetts. WBUR found one licensed practical nurse fired, at the Barnstable jail, in its review of deaths.

Several physicians and criminal justice specialists said there should be independent probes of these deaths, to determine if there was medical neglect or insufficient care.

“It's not enough to simply report the number of people who die,’’ said Dr. Homer Venters, a former medical director of the New York City jail system.

“We shouldn't leave it to a sheriff or commissioner of corrections to say that somebody’s death from diabetes or from heart disease or from suicide or withdrawal was simply a product of their own profile of pathology. Because many of these deaths, in fact, reflect conditions that the person was exposed to behind bars.”

A ‘Baby Boy’

Even amid signs of an obvious medical emergency, WBUR found, inmates were often ignored in jail.

Lidia Lech, 32, was about five-and-a-half months pregnant when she arrived at the Western Massachusetts Regional Women’s Correctional Center on a probation violation.

At her Oct. 4, 2013, intake, medical staff diagnosed the Southampton woman as having a high-risk pregnancy. She later told them of a previous miscarriage.

Over several weeks, Lech complained to medical staff under the Hampden County Sheriff’s Department that she was feeling numbness in her extremities, reduced fetal movement and cramping.

Jail nurses told her to drink water, lie on her side and monitor the fetus’ movement. It would be the first of many times she was told this, according to her lawsuit against the jail and its employees.

Her allegations include the following details:

Corrections officers took her to Baystate Medical Center on Dec. 5 for a checkup. A doctor reported the fetus was active, according to the exam. But within a couple of days, Lech had more troubling symptoms, including headaches, a rash and itching.

By Dec. 23, Lech told jail medical staff she had severe cramping and numbness in her leg, and felt the fetus moving less. She also said she was bleeding. These symptoms continued for about 10 days.

"Ms. Lech also began to experience a feeling of her baby withering away inside of her, making her tremendously afraid of the well-being for her baby."

Dave Rountree

The staff’s advice was the same: drink water, lie on her side and monitor the fetal movement.

“Ms. Lech also began to experience a feeling of her baby withering away inside of her, making her tremendously afraid of the well-being for her baby,” her attorney, Dave Rountree, said in an interview.

Terrified, she begged to go to the hospital. The lawsuit claims staff thought Lech was "stressed out" and “overbearing.”

On New Year’s Day 2014, Lech, in excruciating pain, believed she was in labor. She started to bleed profusely and pleaded with a corrections officer to get help that evening.

Rountree said an officer asked how bad her symptoms were; nursing staff wanted to know if she could wait until morning. Only after a consultation with Baystate did the jail staff send her to the hospital.

A doctor at Baystate detected a placental abruption that put Lech’s health in jeopardy. There was no fetal heartbeat.

The current sheriff, Nick Cocchi, declined to comment on the Lech case, citing the lawsuit. In a statement, his spokesman, Stephen O’Neil, said the women’s jail “provides quality care to all of the pregnant females in our custody, and the Department maintains that Lidia Lech received such quality care while she was in our custody.”

A spokesperson for Baystate, which is also being sued, declined to comment. The state police did not investigate this case.

An autopsy revealed an infection that, the lawsuit claims, could have been treated with antibiotics. The fetus was at least 34 gestational weeks old, but had been dead inside Lech for some time.

The Hampden sheriff’s death records identified him simply as “baby boy.”

Lech had named him Kaiden.

Unexamined Sick Slips

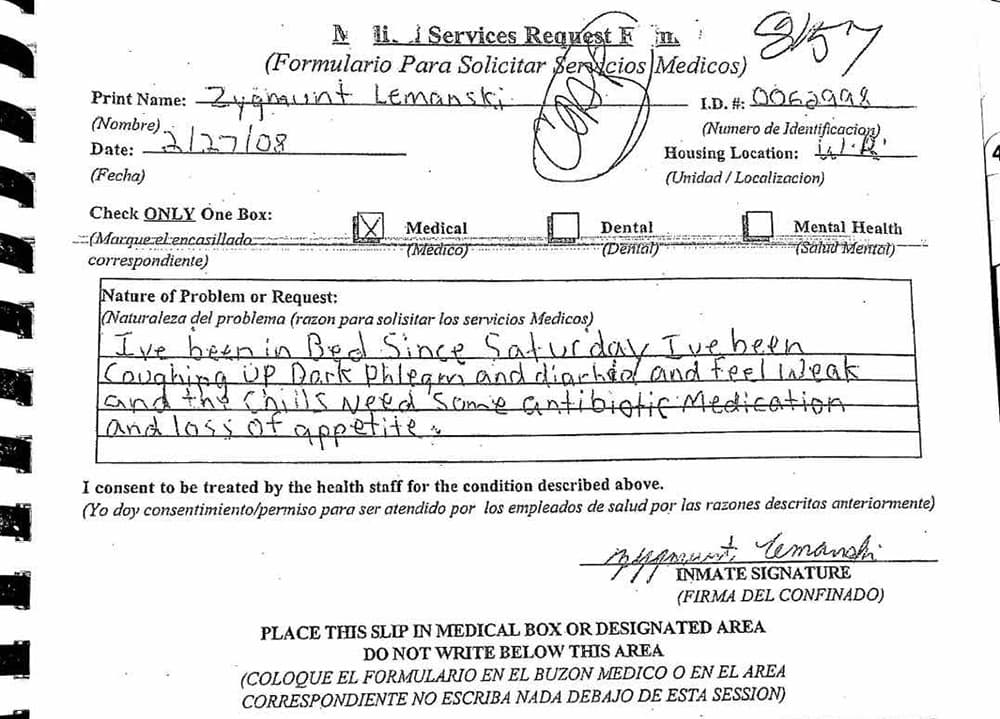

About 60 miles east, at the Worcester County jail, another inmate’s written plea for help was ignored by medical staff.

Jail medical records show Ziggy Lemanski had a weak immune system from HIV and hepatitis C.

Over several days in February 2008, Lemanski felt flu-like symptoms, according to a lawsuit filed by his brother, Mario Lemanski.

Ziggy Lemanski’s condition deteriorated in front of the guards and nurses who gave him his daily HIV medication.

He struggled to get out of bed and was coughing up blood. He wrote to the medical staff that he needed antibiotics.

“I’ve been in bed since Saturday,” he scrawled on a form known as a sick slip, a copy of which was part of the lawsuit against the jail. “I’ve been coughing up dark phlegm and [having diarrhea] and feel weak and the chills.”

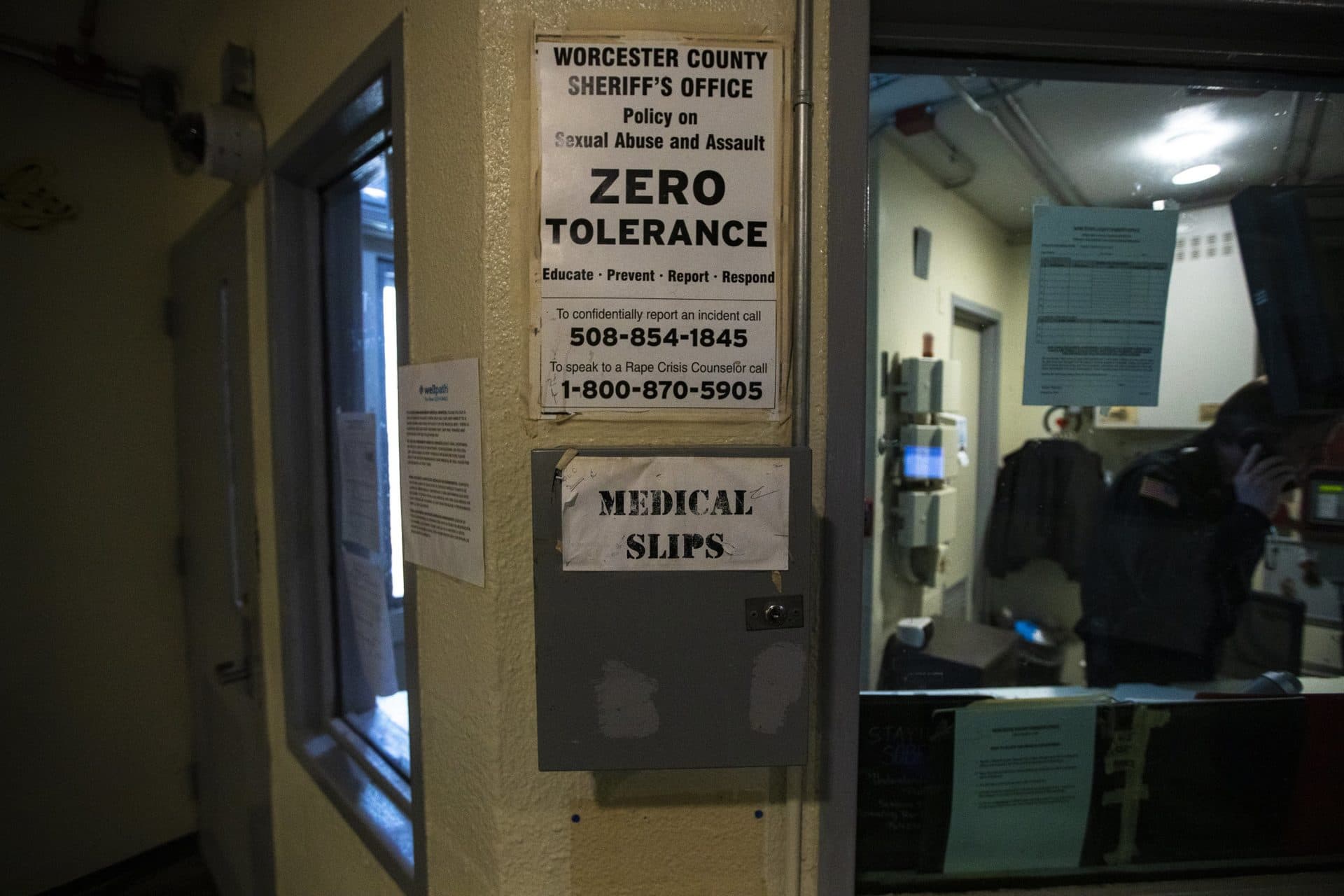

Filing a sick slip, as Lemanski did, is the main way to ask for help in a Massachusetts county jail. It’s a piece of paper inmates fill out and put into a locked box, like a mail slot.

Medical staff are supposed to review a sick slip within 24 hours. But no one examined Lemanski that day, or the next, the lawsuit claims.

When he eventually was sent to the jail’s infirmary, he was dehydrated, his heart was beating rapidly and his oxygen level was dangerously low. On the morning of Feb. 29, an ambulance took Lemanski to Saint Vincent Hospital.

That night, the suit alleges, a jail nurse reported giving Lemanski a dose of medication in his cell. But the nurse couldn’t have; Lemanski was dying in the hospital at that time.

Mario Lemanksi recalls physicians at the hospital apologizing to him, saying, “By the time they brought him in here ... his lungs were so congested they wouldn’t even show up on an x-ray.”

Within days, Ziggy Lemanski died of pneumonia. He was 44.

“If it could happen to Ziggy, it could happen to anybody,” Mario Lemanski said. He spent years seeking justice for his brother.

A decade after Lemanski’s death, a lawyer representing the jail met with Mario Lemanski to settle the lawsuit. The ceiling on suits against taxpayer-funded agencies is generally $100,000, and the lawyer made clear the jail wanted to negotiate an even lower payout, Lemanski recalled.

In 2018, the sheriff’s office agreed to pay Lemanski $62,500.

“In the state’s eyes, his life didn’t mean anything,” he said.

This segment aired on March 24, 2020.