Pain And Profits: Sheriffs Hand Off Inmate Care To Private Health Companies

At the Suffolk County House of Correction in Boston, where hundreds of people are serving short sentences, the sheriff tries to keep inmate trips to hospitals or medical specialists under 80 per month. Escorting them off-site is considered a costly headache.

Suffolk’s medical provider, a Birmingham, Ala., company called NaphCare Inc., is on board: It pays the sheriff’s department a $100 penalty for each trip over the cap.

Rodrick Pendleton, a 51-year-old truck driver and preacher who became addicted to drugs, was under Suffolk County Sheriff Steven Tompkins’ custody in June of 2015. He was in excruciating pain, fellow inmates in the medical unit said. Too weak to stand, he needed a chair to shower. He threw up in a pail for days, just feet from the NaphCare nurses.

“He was way beyond sick,” an inmate told investigators in a recording obtained in a public records request. Pendleton looked like he was dying, the inmate said. “I was just thinking — why don’t they just send him to the hospital?”

A WBUR investigation found inmates in county jails suffering, and sometimes dying, under the care of companies with contracts that provide incentives to curb costs and hospital trips. These for-profit firms are increasingly taking over health care in jails here and across the country — part of a multi-billion-dollar industry with little public scrutiny.

Now more than ever, sheriffs’ medical providers will come under staffing and financial strain amid this looming coronavirus crisis. Visits have been curtailed at jails across the state, and officials are debating whether to release some inmates from their cramped facilities. Sheriffs, meanwhile, are under pressure to show they can keep people safe.

Of the 13 sheriffs who run jails in this state, seven hire outside firms to provide medical care. Those contracts cost taxpayers about $42 million a year.

NaphCare staff finally sent Pendleton to the hospital. But not in time.

“When they paid attention, it was too late,” said his sister, Janice Pendleton. The hospital was “right around the corner. I mean, I don't understand.”

(Editor's Note: Above is an audio excerpt of an inmate being questioned in the internal investigation of Pendleton's death. WBUR obtained it from the Suffolk County Sheriff’s Department. Portions were redacted by the department citing medical privacy. WBUR has shortened those pauses.)

His autopsy would show he’d endured a bowel obstruction, a serious condition that frequently requires surgery. Pendleton was one of 127 Massachusetts jail inmates to die over the past decade of medical causes. The deaths often involved allegations or evidence of poor care.

Jail Contracts Designed To Curb Costs

WBUR found that a bias toward avoiding hospital trips — even in emergencies — is often embedded not only in jail culture, but also in contracts with the private companies that sheriffs hire.

“These companies are inherently motivated to make money. That's why they're in the business,” said Andrew Harris, professor of criminology and justice studies at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell. “There are going to be situations where care is going to be withheld, very often with negative consequences for the patients.”

The same year Pendleton was sick, 2015, NaphCare won a renewal of its contract with the Suffolk sheriff. Just weeks later, NaphCare claimed it had underbid, and wanted to renegotiate, according to records obtained by WBUR.

The sheriff’s department told NaphCare it had to stick to its original bid.

Over the next three years, the sheriff’s department charged NaphCare $2.4 million in penalty fees for inadequate staffing.

Rachelle Steinberg, a Suffolk assistant deputy superintendent, would not say whether the contract terms ever changed. As for the cap on off-site medical trips, Steinberg said they’re designed to be higher than necessary for the roughly 1,400 inmates in the sheriff’s custody. She declined to comment on Pendleton.

“Our providers send people out on a regular basis to the hospitals and have the option to do so should that be medically necessary,” she said.

In 2018, NaphCare paid $1,300 for exceeding the cap, the sheriff’s department said, or the equivalent of 13 additional off-site trips.

“It's hard to imagine a more blatant and inappropriate disincentive to provide care than a financial penalty,” said David Fathi, director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project in Washington, D.C.

These terms can be found in contracts of all three companies that have dominated jail medical care in Massachusetts over the last 10 years.

The Bristol County jail had a cap of 20 off-site trips per month with Correctional Psychiatric Services (CPS) of Braintree. After that, $100 penalties were to kick in. In its contract renewed last year, the cap was raised to 45.

At the Essex County jail, a past contract offered NaphCare bonuses each month of $1,000 if it ordered no more than 15 emergency ambulance trips. A separate $1,000 monthly bonus was offered for keeping off-site referrals under 30.

“NaphCare’s driving force was money,” said Eileen Taylor, a physician assistant for NaphCare at the Essex jail in 2016 and 2017. “It superseded everything else.”

Taylor, who has a workers’ compensation claim against NaphCare and is part of a group lawsuit against the company over pay, said things like urgent blood tests were sometimes overruled due to cost. Other orders, she said, would be reviewed and changed by centralized medical staff, over a thousand miles away.

And NaphCare was reluctant to send people to the hospital, Taylor said. The message was clear: “Don't send them out unless you absolutely, positively have to,’’ she said.

NaphCare executives declined to be interviewed. In an email, spokeswoman Stephanie Coleman said the company “does not override site requests for health care services outside of the jail,” but may confer with providers in the jail and recommend other treatments. She added that NaphCare sends patients to the hospital when necessary.

Officials at Essex, Worcester and Bristol all downplayed the caps and incentives, saying they had applied them rarely, or never.

Essex County jail officials said they removed the bonus provisions when they hired Wellpath to replace NaphCare at the end of 2018. Incentives for reducing off-site visits, the Wellpath proposal said, “could create a negative perception of influencing clinical judgment.”

In 2015, the company that’s now Wellpath Holdings Inc. — the nation’s largest corrections healthcare company — pledged to contain off-site medical spending to no more than $500,000 per year at the Worcester jail. If expenses were less than that, the company would split any money it didn’t spend with the sheriff’s office, 50-50.

“We sincerely believe that as your partner, we should have ‘skin in the game,’ ” the proposal said.

Worcester County jail’s share of the savings with Wellpath totaled $51,000 for 2016 and 2017, Superintendent David Tuttle said. Worcester scrapped the cost-savings deal in its latest contract, Tuttle said, because it could give a bad impression.

Wellpath’s president, Kip Hallman, said contract terms are “almost always established by our clients.” Jails want to save money on medical care, he said, similar to managed care used by employers and insurers.

'I'm Not Going To Make It'

NaphCare was in charge of caring for Kevin Chamberlain at the Essex County jail in March 2017.

The 66-year-old Vietnam veteran had been locked up for 43 days on a probation violation for driving under the influence with a suspended license. He stayed in the infirmary virtually all of the time.

“He was screaming about being in pain,” Taylor recalled.

Complaining in jail is par for the course, and it’s part of why providing medical care is a challenge in that setting. Nurses have to distinguish between inmates who fake or exaggerate, and those who are truly sick or suffering.

“Maybe they'll con you 90% of the time. But you better watch out for the 10% of the time that they're not,” Taylor said.

She recalled that Chamberlain could be cantankerous, but wasn’t a person given to inflating his symptoms.

Chamberlain, known to friends and family as “Chopper,” for his love of motorcycles, had a history of heart trouble and blood clots, as well as post-traumatic stress disorder, according to jail records and his wife, Susan.

“He'd call me at night, and he would cry,” she said. He told her, “I'm not going to make it,” she recalled. When she tried to visit him, she said jail staff told her she couldn’t because, “He’s not medically cleared.”

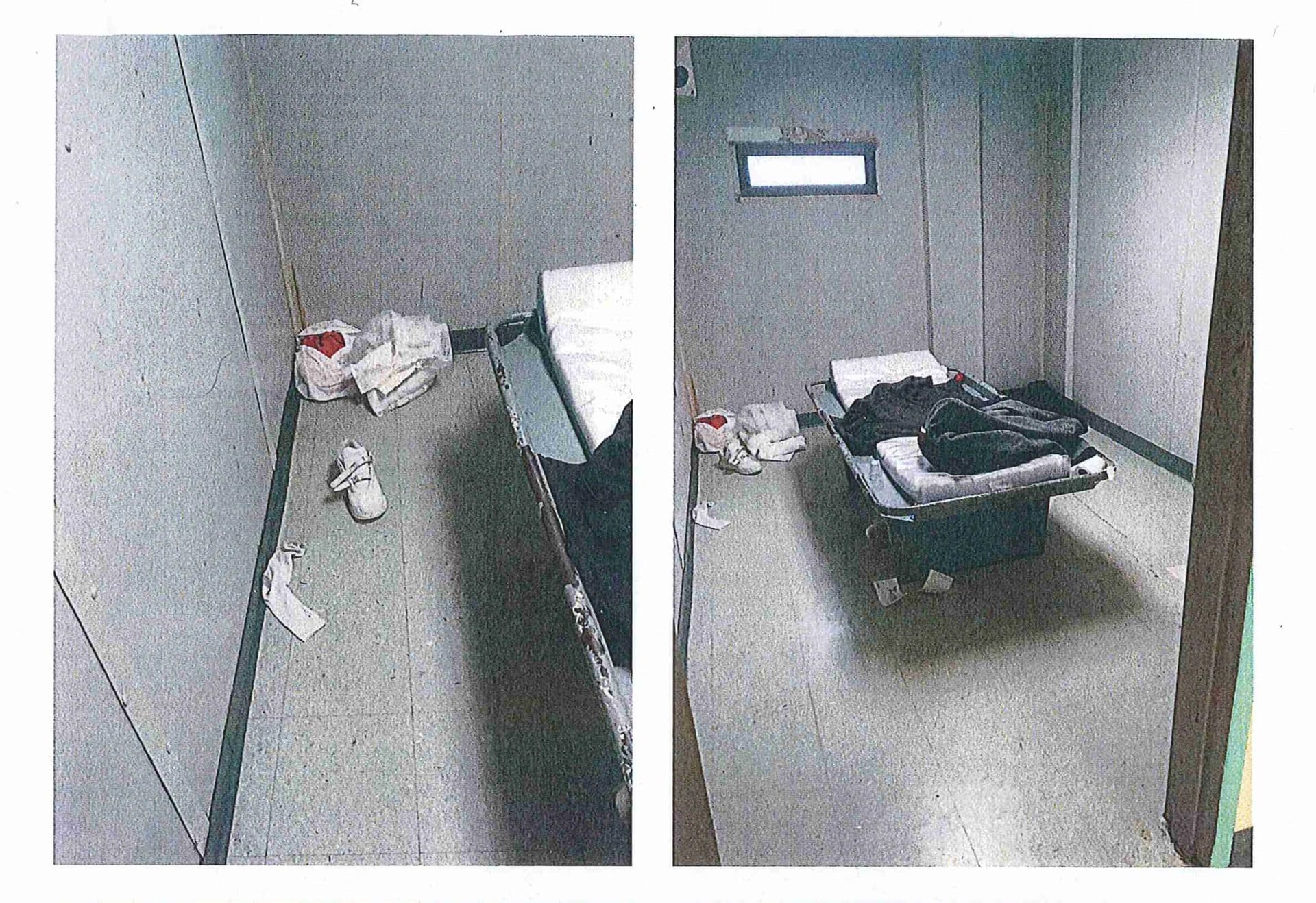

On the night of March 28, 2017, jail records show, Chamberlain slept in “Risk Room 3,” on a metal bed with a thin plastic mattress.

The risk rooms are for patients who need close monitoring. His was directly across from the nurses’ station, where staff could keep watch through the window of the locked door. Guards would report they made “all the appropriate checks during the midnight shift.”

At 6:45 a.m., corrections officer Steven Snow was fixing his tie in the reflection of the window to Kevin’s room — and noticed him not breathing, the records show. The guards unlocked the door and started CPR until an ambulance arrived. Chamberlain died soon after, at the hospital. His death certificate said he died of heart disease and the treatment of blood clots.

Asked whether Chamberlain was ill enough that he should have been at the hospital, Essex County Sheriff Kevin Coppinger said, “That would’ve been a NaphCare decision.’’

He added, “The reason we have the privatized health care here is to turn the care, the medical care, over to professionals, who do that for a career.”

Coleman, the NaphCare spokeswoman, in a statement said Chamberlain received “the highest quality care possible, and we stand by the care delivered.” She said he was “sent to the Emergency Room on multiple occasions” — but did not say when.

Founder Of Jail Medical Giant Indicted

The juggernaut of the jail health care industry was started by a Worcester-area man — Jerry Boyle.

Wellpath, based in Nashville, Tenn., has $1.6 billion in annual revenue and responsibility for nearly 300,000 inmates in 33 states. It’s one of two national jail medical giants that Boyle had a hand in creating.

Boyle had seen how bad health care could be in jail. He started as a prison guard and rose through the ranks to superintendent of Bridgewater State Hospital in the late 1980s to early 1990s. In those days and well into recent years, Bridgewater, an hour south of Boston, was a place where people with mental illness often suffered through poor health care, died or were forgotten entirely.

Boyle would parlay his 15 years of corrections experience into a second career in the private jail health care business — this time for profit.

He first led a company called Prison Health Services, which had the Suffolk jail contract in the early 2000s and later became part of Corizon Health.

Clients around the country followed him to his next company, Correct Care Solutions. Boyle attracted private equity backers, including Boston-based Audax Group, that saw prison medicine as ripe for cost savings and potential investment payoffs. Several mergers later, the company is now owned by the Miami investment firm H.I.G. Capital, and rebranded as Wellpath. (Wellpath is a financial underwriter for WBUR. It had no editorial involvement in this story.)

Boyle, 65, was indicted in October 2019 on charges of allegedly bribing a Norfolk, Va., sheriff with cash and gifts for contracts. That sheriff, Robert McCabe, was indicted too. He was one of Boyle’s references when vying for business in Massachusetts: “As a client, I feel valued and this sets CCS apart from your competitors,” McCabe said in a proposal document.

Both Boyle and McCabe have pleaded not guilty and resigned from their jobs. Boyle left the Wellpath board in October, the company said. The men are scheduled to face trial in May.

The charges marked the end of a long and lucrative run for Boyle, described by associates as an affable businessman who was good to employees. Wellpath executives said Boyle had no day-to-day role at the company after 2015. But his local ties and position as board chairman helped the company win contracts with the Worcester and Essex County jails, the state prison system and Bridgewater State Hospital, his former employer.

In a Nov. 9, 2018, letter to Boyle, Coppinger — the Essex sheriff — congratulated Wellpath on winning the contract. He hand-wrote in the margin, “Looking forward to working with you!”

Boyle was under investigation in Virginia by that time. Through his lawyer, Boyle declined to be interviewed.

Companies Face Lawsuits Nationwide

Unlike elected sheriffs, contractors such as Wellpath aren’t subject to public records laws. Most have used that as a reason, along with privacy concerns, to keep records secret, making it difficult for families to hold them accountable. Often, the only way to do so is to sue.

Beyond providing staffing, these companies also shoulder a large portion of the liability that can come with jail care when things go wrong.

“This is a litigious environment,” Hallman, the Wellpath president, said. Sheriffs “see us as being a solution to that problem.”

Share your story or send our investigative team a tip. Plus, sign up to get WBUR investigations in your inbox. And listen to this series on your smart speaker.

Legal complaints against medical companies and sheriffs range from allegations of neglect submitted in longhand by inmates on their own — and often dismissed by judges for lack of evidence — to those filed in state or federal court by lawyers alleging civil rights violations under the U.S. Constitution.

Wellpath and its predecessor company, Correct Care Solutions, have faced some 1,200 lawsuits from inmates or families in federal courts across the U.S. in the last five years.

Both Correct Care Solutions and NaphCare have boasted in marketing materials or bids that they’ve never lost a legal case. But behind the scenes, they have settled lawsuits totaling millions of dollars, according to court records and news reports.

In 2018, Wellpath paid a family $525,000 after a man died from a bleeding stomach ulcer at a jail in Norfolk, Va., where McCabe used to be sheriff. The company told WBUR it does not discuss patients or lawsuits.

And NaphCare, in just one example, paid a family $500,000 after a 28-year-old man had a seizure and died while restrained by guards and medical staff at the Montgomery County jail in Dayton, Ohio.

Here in the commonwealth, at the Suffolk County jail, NaphCare was sued by a man who alleged that a severe reaction to antibiotics put him in the hospital for weeks, skin peeling from his body. And at the Essex County jail, a man sued the company for failing to provide prompt care for his broken back. NaphCare settled both cases and required non-disclosure agreements.

Waiting, And Dying

Kelly White’s family members didn’t have the resources to sue. They never felt they got the full story of what happened to her in the Bristol County jail.

A longtime heroin user, White had been picked up on a warrant in 2012, for owing the New Bedford court $200 in court fees.

Jail records show nurses ordered White twice in the same morning to be sent to the Bristol infirmary, overseen by Correctional Psychiatric Services Inc. (CPS).

But she never made it there the second time. White, 42, died in a maintenance hallway, waiting for a ride to the infirmary, one building away.

She was feeling sick and complaining of symptoms that are blacked out in the jail records. The sheriff's investigative records, citing a medical examiner’s report, say she had a heart infection.

“Her cellmate told me she knew she was going to die,’’ said Abigale Mulstay, White’s sister. “How much pain do you have to be in to say to yourself, ‘I’m dying’ ?”

At the Bristol County jail, 31 people have died in the custody of Sheriff Thomas Hodgson and CPS over the past decade, WBUR found. That’s the same number as at the larger Suffolk County jail, and more than at any other jail in the state.

Seventeen of the deaths were due to medical causes such as cardiac arrest, septic shock and cancer. The rest were suicides.

CPS is owned by Dr. Jorge Veliz, a psychiatrist and former medical director of Bridgewater State Hospital. He started CPS in 1994, later expanding from mental health into medical care.

Images on his company’s website strike a decidedly corrections-oriented tone: closeups of barbed wire and handcuffs on a keyboard. Veliz has won contracts with four major jails in Massachusetts. He’s also donated regularly to all of his client sheriffs’ election campaigns — more than $7,000 since 2013, including to Hodgson.

The longtime sheriff of Bristol County is known for controversial measures tough on inmates, like charging medical co-pays and allegedly putting mentally ill inmates into segregation too often. He’s facing a class-action lawsuit from those inmates and has recently been criticized for the overcrowding of ICE detainees.

In an interview, Hodgson said his jail, like others in the commonwealth, has become a kind of hospital, because so many inmates have medical issues and addictions. Still, he said, “It’s never to our advantage to fall short of giving the proper care to anybody here.”

Hodgson couldn’t say why White wasn’t sent to a hospital sooner. He deferred to CPS, saying, “They’re the medical experts, not me.”

CPS executives declined to discuss White’s case. The company’s chief operating officer, Beth Cheney, said, “The last thing we want is to have people die.”

White had been at Bristol for just four days when she died on March 16, 2012.

The first several days in jail can be especially dangerous for new inmates withdrawing from drugs. They often suffer from nausea and dehydration, doctors say, and these symptoms can overshadow other health issues.

White was suffering not only because she was coming off drugs, but also from the heart infection, which, doctors say, could have been treated with IV antibiotics.

“She died a miserable death,” White’s sister, Mulstay, said. “It's a human life. They come with family and friends and history. They come with what-could-have-beens.”

This segment aired on March 25, 2020.