Advertisement

From Strandbeests To ‘Renoir Sucks’: The Best Art Around Boston In 2015

The most exciting thing about art around Boston in 2015 was how it broke out of museum walls and took to the streets. This year saw the revival of “Sculpture Racing”; giant, blowing bunny rabbits infest the Boston Convention Center; protests at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts against (alleged) Orientalism and the long-dead French Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir; and a figure appear out of the blue, 44 stories up the city’s tallest skyscraper. The result was a new feeling of engaging populism and public spectacle in the city’s art.

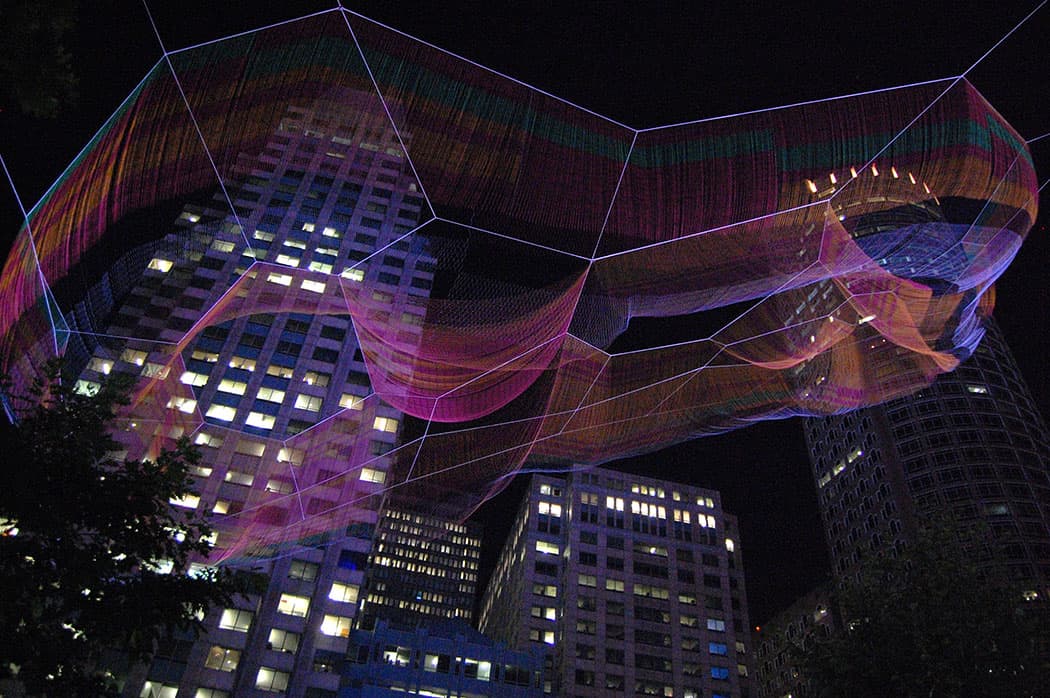

Janet Echelman’s “As If It Were Already Here” at Kennedy Greenway

For years now, word had been trickling back about the knockout public sculptures Brookline artist Janet Echelman had put up in Denver, Amsterdam, Sydney, Vancouver. Finally in May, she was able to do one for the hometown crowd—and her art lived up to the hype. By night, the half-acre of net suspended between three skyscrapers high in the air spanning Boston’s Rose Kennedy Greenway pulsed with lights—red, orange, blue. It was like a spider web to catch cosmic dreams.

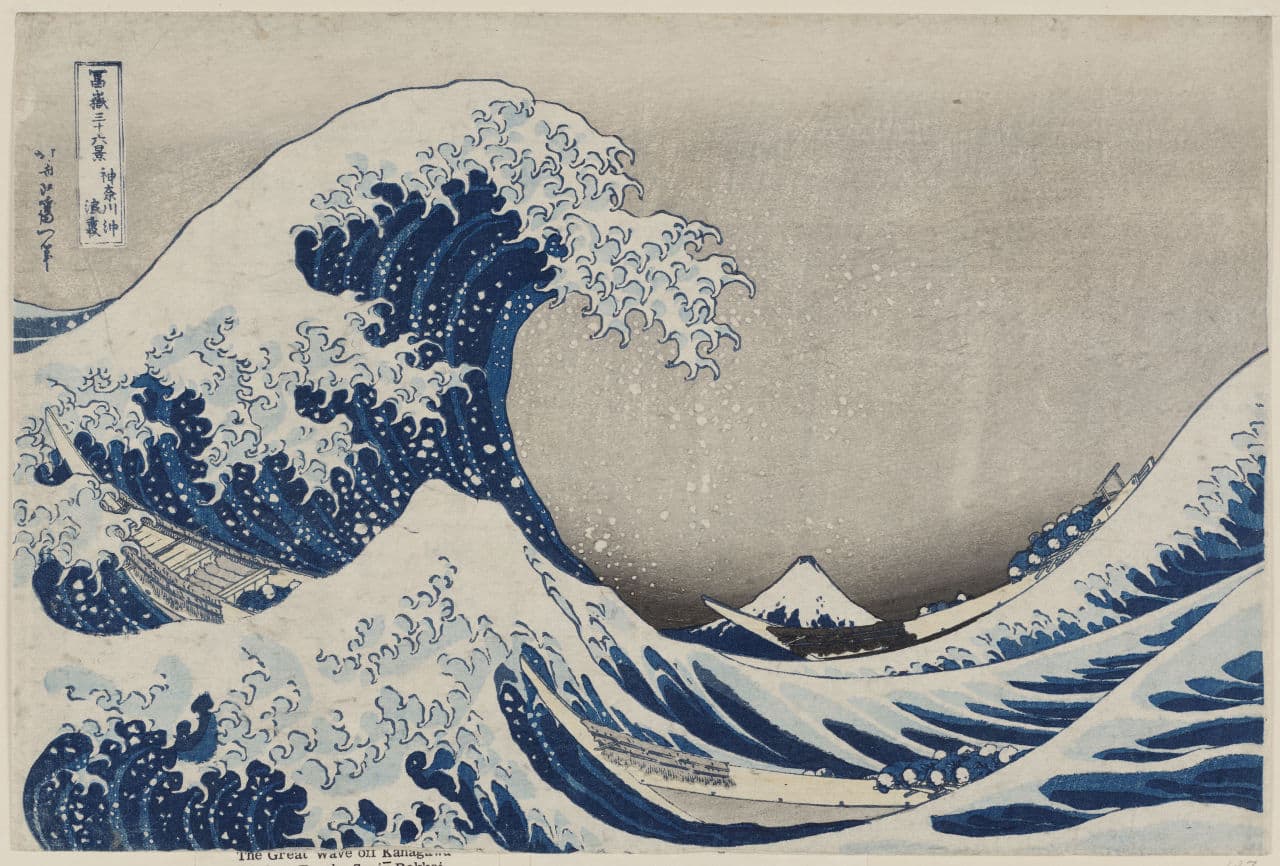

“Hokusai” at Museum of Fine Arts

Katsushika Hokusai, the 19th century Japanese master, is best known for his iconic “Under the Wave Off Kanagawa (Great Wave),” one of the most famous images in all of art. That woodblock print was the centerpiece of this sumptuous Museum of Fine Arts retrospective, which offered a deep dive into the rest of his landmark career—depicting cities and Mount Fuji and demons in so many sensual, ethereal shades of blue.

“People’s Sculpture Racing” at Cambridge River Fest

When Christian Herold moved back to Cambridge in 2007, he recalled, “I asked where is Sculpture Racing and everyone shrugged their shoulders.” World Sculpture Racing, as it had been known, was a series of races held annually from 1982 to ’85 in which people raced wacky sculptures through the city’s streets. For real. It was part art, part engineering, part absurdity, part sports. In June, Herold revived the tradition and some 16 sculptures arrived for a madcap, 3/4-mile race at the Cambridge River Fest—a 23-foot-long fish, a giant rat trap, a cart of rolling mechanical waves, a flock of mechanical birds, a sailboat riding atop square wheels. Amazing.

“Decolonize Our Museums” protests at Museum of Fine Arts

In July, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts announced that is was cancelling its event called “Claude Monet: Flirting with the Exotic” and “Kimono Wednesdays,” which had invited visitors to try on the traditional Japanese garment and pose in front of the museum’s Claude Monet painting “La Japonaise,” which depicts the French artist’s wife doing the same. The museum’s move was in response to a group of protestors calling themselves "Stand Against Yellow Face” and later “Decolonize Our Museums,” lead by Amber Ying, Loreto Paz Ansaldo and Pampi Thirdeyefell. For several Wednesdays, they stood in the gallery with signs charging that the museum’s “exotic” approach to Japanese culture was racist, Orientalist and imperialist. The protests sparked international debate about (1) when is it appropriate for people of one culture to imitate or appropriate the culture of another people and (2) who gets to say. When new MFA Director Matthew Teitelbaum arrived, one of his first public acts was to sit down in October with the protest leaders for a chat.

Amanda Parer’s “Intrude” at The Lawn on D

In May, five, two-story tall bunnies took over the Lawn on D, the hit showcase of art and music offered by the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center since summer 2014. For Australian artist Amanda Parer, her monumental rabbits were a statement about the dangers of invasive species—including imperial peoples. But thousands came out to see them and just enjoy the cool spectacle of the bunnies’ monumental cuteness, lit-up from within, on a handful of warm summer nights.

“Strandbeest: The Dream Machines of Theo Jansen” at Salem’s Peabody Essex Museum

When Dutch sculptor-tinkerer Theo Jansen’s wind-powered robots made their first local appearance at Crane Beach in Ipswich one Saturday morning in August, it was such a sensation that traffic was backed up for miles. The jam was a drag, but the public displays of the “Strandbeests” (Dutch for “beach animals”) there and later at Boston City Hall, as well as the exhibit at Peabody Essex Museum in Salem were magical. Jury-rigged robots, powered by wind, that walk like insects with minds of their own. Besides the dazzling machines themselves, a marvel of the exhibit (on view through Jan. 3) is that you’re allowed push the Beests yourself for a hands-on engagement with Jansen’s wondrous ideas.

Marka27 mural at Tobin School

Cambridge artist Caleb Neelon and friends (Katie Yamasaki, Risk, etc.) have been quietly turning the Tobin K-8 School in Boston into a local showcase for graffiti and murals. The paintings are hidden all over the Roxbury school’s campus. Late last summer, one of the best (so far) appeared: a monumental, crowned figure painted by Boston artist Victor “Marka27” Quinonez (with a little help from Neelon).

JR Photo-Mural at 200 Clarendon

The 7-story-tall, black-and-white figure appeared 44 stories up the 200 Clarendon skyscraper (formerly known as the John Hancock Tower) one morning in September and became the talk of the town. What was it? Who was behind it? The apparition turned out to be a secret, surprise project by the French artist JR, who blows photos up to gigantic proportions as murals. As more of the Boston image was pasted up, it turned out to be a giant person standing on a raft that seemed—in a magical touch—to float atop a sea made by the building’s signature blue windows.

“Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957” at the Institute for Contemporary Art

The legendary, utopian, anti-hierarchical, anti-institutional school in North Carolina lasted just a quarter century, but cast a long shadow in 20th century American high culture. In this deep dive ICA research project (on view through Jan. 27), the college won institutional embrace. The ICA wasn’t so interested in the school’s radical philosophy, pedagogy or poetry, but in assembling an astonishing array of vintage paintings, photos and films to position it as the incubator of high New York modernism of the 1940s and ‘50s—Willem de Kooning’s Abstract Expressionist paintings, Merce Cunningham’s dance, John Cage’s radically random musical compositions, and Robert Rauschenberg’s magpie combine assemblages.

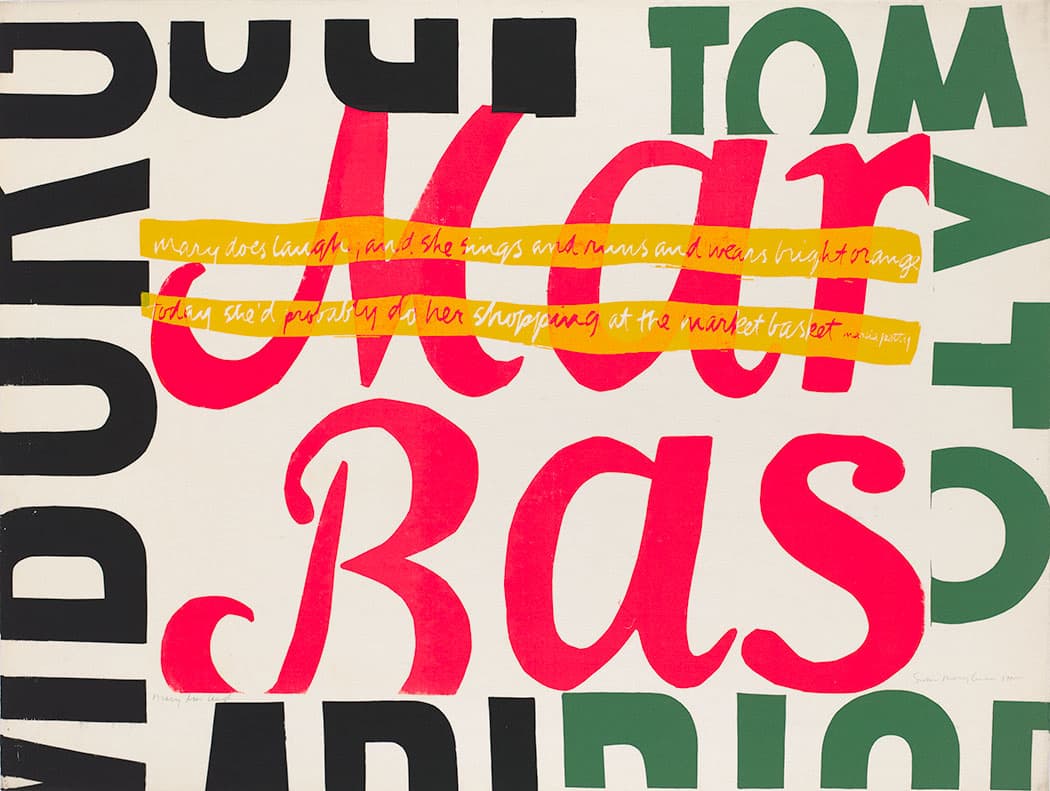

“Corita Kent and the Language of Pop” at the Harvard Art Museums

Corita Kent (1918-1986) was one of the most famous Catholic nuns in the United States during the peak of her career in the 1960s. She was infamous as well for her radical, liberal take on faith and politics as she made catchy pop art prints in Los Angeles and, beginning in 1968, Boston. Best known around these parts for her 1971 rainbow swoosh design for the Boston Gas (now National Grid) tank located alongside I-93 south of downtown Boston, Kent spread a gospel of joy by adopting the language of pop to celebrate the sacred bounty in the everyday cornucopia lining our supermarket shelves. Her prints were also calls to end hunger (quoting President Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty” speeches), racism and the Vietnam War. And they mourned the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. The exhibit (which continues through Jan. 3) attempts to shoehorn Corita into the pop art canon by putting her amongst a bunch of so-so prints by nonpolitical male Pop artists. The strategy is flawed because it sidelines the faith and politics at the heart of Kent’s accomplishments. But the energy of Kent’s art shines through. And Kent herself was never one to turn down opportunities to have her work seen even when the circumstances were, um, complicated—because her goal was always to spread the word.

“Renoir Sucks” Protest at Museum of Fine Arts

In October, Max Geller led six friends and a couple strangers in a protest in front of the Museum of Fine Arts. The target of their ire? The art of the celebrated French Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who’s been dead since 1919. Signs read: “Treacle harms society! Remove all Renoir Now,” “God hates Renoir,” “Renoir sucks!” The protest became international news. At first glance, it was a grand joke about a painter that many art insiders already had mixed feelings about. But underneath, Geller was leading an insurgency that asks a serious question: Who gets to decide what gets featured in our museums?

Let ARTery co-founder Greg Cook know what you think was the best art of 2015 on Twitter @AestheticResear or on the Facebook.