'I Was Afraid Every Day': Mass. Residents Reflect On A Year Of COVID-19

Nurse Ellen Stephenson pushes her arms through the sleeves of a yellow plastic gown outside a COVID-19 patient’s room at Boston Medical Center. She fits a mask and shield over her face, and pulls on a pair of purple rubber gloves, then a second pair after that.

Finally, she opens the patient’s door, balancing a breakfast tray and meds in her arms — four hours worth of needs to be met in a single visit. The door closes with a click, and a man’s deep cough echoes through the hallway.

A year after the first confirmed COVID case appeared in Boston, this is still the grim routine in the special contagious disease unit at the hospital. On Feb. 1, 2020, a UMass Boston student was diagnosed with the virus, back when it seemed like a distant malady, something linked to China, a mystery illness that had not yet come too close.

"Go about your daily life," was the word from state and federal officials. And wash your hands. But in medical circles and at hospitals, experts knew a dangerous threat was brewing.

“It was a constant conversation in February,” said Kate Baudin, nurse manager of the special unit at Boston Medical Center. “It’s coming, it’s coming, it’s coming.” Even so, she said, the staff could never have imagined how the virus would consume their work — and, as it turned out, all of life as we know it.

On March 13, the day arrived.

“It started out like a normal day and then the call came through,” Baudin said. It was afternoon, and there was a confirmed case coming to the unit. She took a deep breath and called a huddle with the staff. “It’s been the rock that’s been rolling towards you for days,” she recalled thinking. “We talked about how this is what we’ve trained for. It’s super scary. But they know what they’re doing.”

"It started out like a normal day and then the call came through."

Kate Baudin, Nurse Manager at BMC

There were three positive coronavirus patients in the unit by the end of that first day. The days that followed were a blur of COVID cases for the 38-bed unit and other sections of the hospital too, Baudin said.

Just days after BMC’s first case, Gov. Charlie Baker shut down schools, large gatherings and in-person dining at bars and restaurants across the state.

It was supposed to be precautionary, for three weeks. That was stunning enough. Then came the closure of all nonessential businesses. And the weeks turned into months, and, for many, it’s been the strangest year in memory. Mandatory masks. Endless Zoom meetings from home. Boredom and isolation.

Veronica Truell is pastor of First Baptist Church in Norwood, a small congregation with a larger following on Facebook since March. She says what her members miss most is gathering in person, eating meals together and talking.

“The inability to hug somebody,” she said, has made some people sad. “We understand the coronavirus and the need to stay safe — they are definitely on board with staying safe. But it’s really, really hard.”

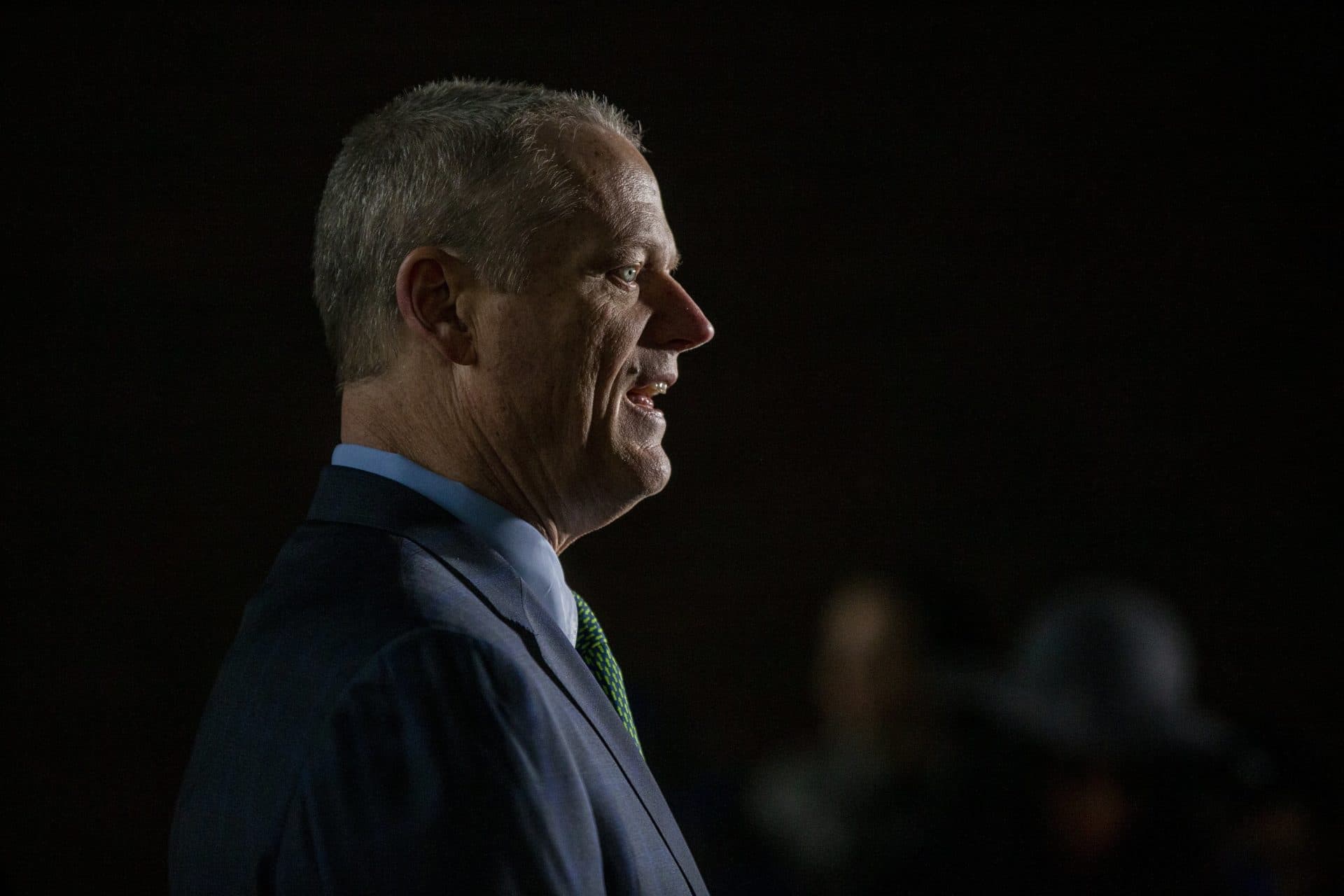

“I never would have thought that when we first found the first case that we would be in the situation that we're in, and the situation that we continue to focus on day in and day out.”

Marty Martinez, Boston's chief of Health and Human Services

Even worse: For many people, especially essential workers, the pandemic has brought grave danger.

Marty Martinez, chief of Health and Human Services for the city of Boston, remembers getting the call about the first case. It was a Saturday, and he was home with his family.

“I never would have thought that when we first found the first case that we would be in the situation that we're in,” he said, “and the situation that we continue to focus on day in and day out.”

Now, a stunning half-a-million Massachusetts residents have contracted the virus. More than 14,000 have died. And the state is struggling to provide long-awaited vaccines to anxious workers and seniors. Many people are frustrated by the system, and by how long it could take to get a vaccine.

Martinez acknowledges that he never imagined the pandemic would last this long, or change life in the city so dramatically.

After that first case — the UMass student who had traveled from China — the virus started rearing its head in many places. There was the infamous Biogen company conference. Held in late February at a downtown hotel, it would ultimately be known as one of the early superspreader events, linked to more than 300,000 COVID cases around the world. There were later outbreaks at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the Holyoke Soldiers’ Home and Boston College. The virus has taken an especially heavy toll in communities of color.

For Joao Goncalves, an MBTA bus driver who runs Route 111, from Haymarket to Chelsea, the job he loves turned into a dangerous daily mission last March.

In the early days, he said, the buses were still packed, with people standing shoulder to shoulder. And some people refused to wear masks, endangering everyone around them.

“In the middle of the pandemic, the virus was crazy, especially in Chelsea,” he said. “I was afraid every day.”

He’d go to work early to give his bus an extra cleaning, Goncalves said. He spent his own money to buy sanitizing spray and extra wipes. “I’d leave the house with no desire to go to work — for the first time in my life, you know? I was afraid,” he said.

And he was afraid of giving the virus to his wife and children. Since last March, he said, he has slept in a guest bedroom at his house.

Essential workers across industries have had the same worries for the safety of their families. And months of stress have taken a toll — not least when many people ignored warnings against gathering around the holidays, causing a new surge in cases that is just starting to wane.

“They’re tired,” Baudin, of Boston Medical Center, said of her staff. “I know they’re tired. It’s a lot. It would be nice to get back to normal, whenever that will be.”

"It would be nice to get back to normal, whenever that will be."

Kate Baudin, Nurse Manager at BMC

Goncalves said he can’t understand why transportation workers weren’t higher on the list to get a coronavirus vaccine. While hospital employees, first responders and other health care personnel have been offered vaccinations, other essential workers won’t become eligible until later this month, at the earliest. He’s encouraged that their time should finally be coming; it gives him hope. But it can’t happen fast enough, he said.

In a bus, “You close the door, you’re in a closed box,” Goncalves said. “I'm just hoping this vaccine comes up for us quick — and so maybe I’ll feel more comfortable.”

This segment aired on February 1, 2021.