How COVID Isolation, Loss And Racism Deepened Crises For Children Of Color

The pandemic is waning, but the mental health crisis for children isn't. And for many children of color, the full impact of the last 15 months — against a backdrop of longstanding systemic racism and inequities — may just be coming into focus.

Mahailya Effee, a 15-year-old who lives in Roxbury, says from the early days of the pandemic, she struggled to stay engaged with full-time remote school. She started to not care about her grades.

"I would wake up in the morning; I'd have my Chromebook right there in front of me," Mahailya said. "I would do the work. I just wouldn't finish it and turn it in."

Mahailya already had anxiety, and she hated being stuck in her family's apartment. Then, the pandemic really hit home in May of last year. Mahailya's grandfather died from COVID-19. She vividly remembers the moment her mother got the call.

"And I was like, 'Nah, this can't be true,' " Mahailya recalled. "So then I went in the bathroom, and ... I wasn't yelling, but I was just like, 'Why?' "

Her grandfather had been homeless in Boston. She was devastated the family couldn't hold a funeral for him because of the health risks.

"It was just like, he's gone. I can't say a final goodbye," she said. "And to me, a funeral is when a person might be gone, but their body is there in the casket, and you can see them. It was really stressful, and I kind of started overeating."

She started to fail classes. At around the same time, the city and nation erupted in protests over the police killings of George Floyd and other Black people. Mahailya says Floyd's murder made her angry.

Children of color who live in the cities most affected by the pandemic have been hit by a triple tsunami: Their communities have had higher rates of COVID infections and deaths, more job losses, and more isolation from extended remote learning than many predominantly white suburbs.

They've also faced added trauma related to racial injustices and a broader societal reckoning over race and police brutality.

Last summer, two advocates from the Cory Johnson Program, a trauma healing initiative at Mahailya's church — Roxbury Presbyterian — learned of her struggles in school. They stepped in to support and guide her. Her mother had been in the program for some time; the clinicians and advocates from the program work to help the whole family.

Community Trauma Healing Specialist Shondell Davis says tensions at home during the pandemic could set Mahailya off. At one point, she called Davis in tears.

Advertisement

"Just saying that she had to get out of there," Davis recalled. "She was crying her life out, like, 'I can't do it, I can't stay here no more.' "

'Kids That Would Have Never Had Mental Health Challenges'

Pediatric clinical psychologist Fatima Watt worries the pandemic has increased disparities for children of color — and that the stressors of the last 15 months have triggered more mental illness in kids.

"I think that there are kids that would have never had mental health challenges, would have never seen the inside of a hospital, if it weren't for the pandemic," Watt said.

Franciscan Children's in Brighton says it saw a 19% increase in children of color in its mental health programs in the year after the pandemic started, compared to the year before.

Demand is so high, patient coordinators have to tell callers it'll be a six- to 12-month wait to start outpatient therapy. The wait in normal times was about one to three months, according to Watt.

"It's upsetting for [our staff]. They hate not to be able to provide something for the patient right away," she said. "And for families, it can contribute to their despair, like, 'My kid needs help now, and you're saying I can get help in a year?"

Watt says the crisis seemed to hit a peak recently. Even as the pandemic settles down, more kids need help for anxiety, depression and trauma.

"They're starting to grieve for loss of grandparents, loss of parents," she said. "We've seen an increase in referrals for children who've lost one or two caregivers."

They grieve for missed milestones, too. Watt describes kids who feel lost — and who've spent a year worried about parents who have to work in jobs that were risky.

"They're starting to grieve for loss of grandparents, loss of parents. We've seen an increase in referrals for children who've lost one or two caregivers."

Fatima Watt

Meanwhile, many parents have been so stretched, they've put off mental health challenges of their own. It can be difficult to focus on emotional needs when so much energy is required just for basic survival.

"You're like, 'I got to feed my kids. I got to have somewhere to live, so I'm not sleeping in my car. I can't be thinking about depression, anxiety,' " Watt said. " 'You want me to do what? You want me to do what behavioral strategies to manage these tantrums? Yeah, I don't have the brain space for that.' "

A team at Franciscan supports families who need immediate advice or assistance with resources, from toilet paper — when that was hard to come by — to transportation, Watt says. The staff tracks kids waiting for treatment, so the families know they aren't alone.

In Brockton, 'People Still Feel Like COVID's In The Air'

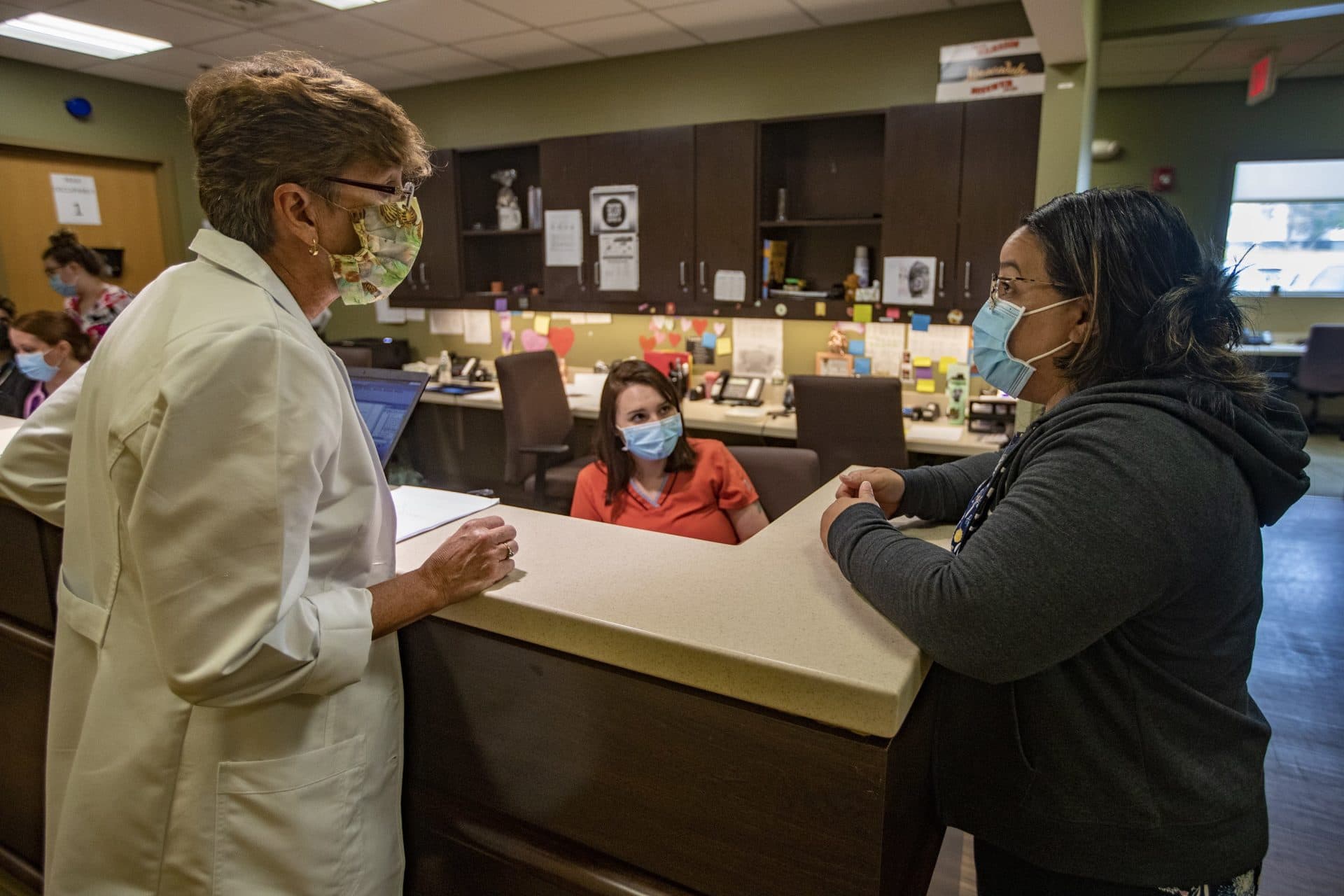

Doctors and social workers at Brockton Neighborhood Health Center also rely on a team approach, to make sure kids don't fall through the cracks in the pandemic.

Each "teamlet," as they're called, has a mental health clinician who assesses kids and sets them up with therapists at partner agencies.

The teamlets also have a community health worker who connects families with resources.

"That could be housing, food stamps," Jessica Miranda, one of the community health workers, said. "They could be food pantries, connecting them to get transportation to the appointments — anything under the sun that a social worker may not have the time to help them with, we try to connect them with."

Head pediatrician Janemarie Dolan has spent a lot of time focused on the coronavirus fears that have gripped a lot of her patients' families.

"I've had families that will not leave the house," Dolan said. "There was so much COVID here. The incidence was so, so high ... that a lot of people still feel like COVID's in the air. They can't go outdoors."

She encourages patients to think of 2020 as the year of COVID and 2021 as the year to get healthy again: "You need to be outside. You need to [feel] the fresh air. You need to get some exercise," she said she tells them. "You know, that overall wellness is going to help your mental health."

On a recent afternoon, Dolan ran from appointment to appointment. One boy revealed he was somewhat depressed, and a girl realized during her visit with Dr. Dolan that she's developed anxiety.

"She's like, 'Yeah, I'm just in my head all the time. Thoughts, thoughts, thoughts, worrying about this, worrying about that,' " Dolan said, "to the point where she doesn't want to sleep, because she's so worried that she's going to be worried about things."

That kind of open talk about emotions and distress doesn't come easily for some patients. Dolan says many of the immigrant communities the health center serves rarely talk about mental health; so it's tough when she has to explain to parents that their children are depressed to the point of being at risk.

"We might not say suicidal, but we're worried about their safety and explain that some kids are really sad and sometimes want to hurt themselves," Dolan explained. "Some parents will get upset with it."

Last fall, the health center had to section, or involuntarily commit, more children than normal to hospitals for evaluation — about one child per week, according to Dolan, who says the number of hospitalizations has remained higher than before COVID.

She says most parents and guardians consent once the team explains that their children really need to go to the hospital. Still, it can be hard to convince families to engage in therapy after that.

Calls For 'Culturally Responsive' Care

Dr. Fatima Watt at Franciscan Children's says she knows something that would help more families of color get on board with therapy.

"Culturally responsive care, that every person of color can walk into any agency and get care that is appropriate for them," Watt said. "The question is, can you get into the room and see someone who can actually meet your needs, who can be culturally responsive, who can not perpetuate discrimination and bias that you have on the outside world?"

Watt says the pandemic highlighted the need for more clinicians of color, as well as white clinicians who want to learn how to provide that care. She adds that research has found families of color are more likely to discontinue therapy after a short time.

She recently had a breakthrough with a Black adolescent who looked for help for a long time.

"She had seven clinicians before me, and all of the seven clinicians didn't know how to work with her," Watt said. "And the mom says, 'I know there's something wrong with my kid, and I don't know how to find someone who can help her.' "

Roxbury teen Mahailya Effee sought out a new therapist during the pandemic.

"It helps me with, like, just talk about what's going on in my life and my anger, because I struggle with that," she said.

And she found a different kind of support from the trauma healing team at Roxbury Presbyterian.

Mahailya's "community companion" from the program, Judelle Cummins, let Mahailya drop by her place to vent and hang out during the pandemic. Cummins checked in with her teachers and worked with Mahailya to set goals. The first was just to just attend her remote classes. Then, to take notes. And finally, to call Cummins every day with an update on how she was doing.

"I just wanted to create a space where she can be herself and not feel as though I was trying to make her become something that she wasn't," Cummins said. "But for her to actualize who she really is underneath all the stuff that's going on outside."

Mahailya brought up her grades to As and Bs, and is trying to keep working through the daily struggles of being a teen during these tough times.

"I mean, from where you started out to where you are now, it's like, 'I'm sorry, Mahailya who? Who's this girl?' Congratulations," Cummins said, as she, Mahailya and Shondell Davis laughed.

Mahailya answered, "Thank you."

This project is funded in part by a grant from the NIHCM Foundation. Illustrations and animations in this series were created by Sophie Morse.

This segment aired on June 24, 2021.