Advertisement

Why the UN climate conference matters to Massachusetts

There's a big climate conference going on called COP26. Yes, it's a terrible name. In fact, the conference is full of weird acronyms and strange numbers.

We're here to help.

This FAQ will demystify COP26 and explain what it means for you — yes, you! — if you live in Massachusetts. Let's kick it:

Another climate conference! What's this one about? And where'd they get that name?

The 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference, or "COP26," is running through Nov. 12 in Glasgow, Scotland. "COP" stands for "Conference Of the Parties" and includes all the countries involved in international climate negotiations — 197 in all. They meet every year and this is the 26th time they've met. So, COP26! Ta-da!

During COP26, world leaders will review — and hopefully improve — their plans to lower their country's greenhouse gas emissions.

Didn't they already do this?

Yes! In the 2015 Paris Agreement, countries agreed that they should limit global warming to under 2 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, preferably closer to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Trouble is, the world is not yet hitting either of those targets.

According to the very handy Climate Action Tracker, right now we're heading toward 2.9 degrees Celsius by 2100. The goal of the Glasgow conference is to get everyone to agree to lower emissions so we're heading more toward 1.5 degrees Celsius.

1.5 degrees, 2 degrees, 2.9 degrees — none of those sound like very much. I mean, this is Massachusetts! It can change 10 degrees before breakfast. What do these numbers actually mean?

These annoyingly teeny Celsius numbers are global averages. The world has warmed about 1.1 degrees Celsius — on average — so far.

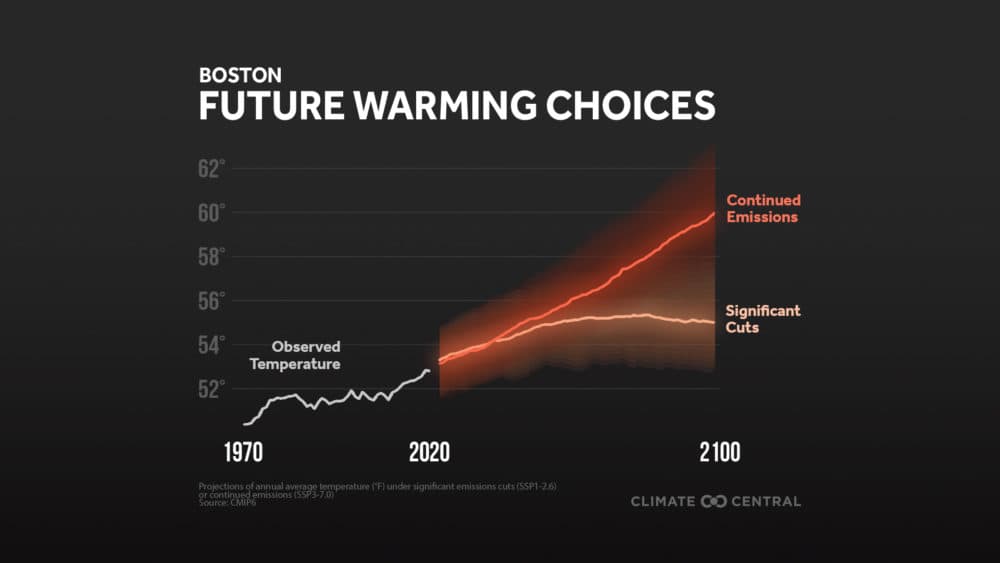

In Boston, that translates to about about 3 degrees Fahrenheit of warming since 1970. In other words, the average temperature in Boston over the year used to be about 50 degrees Fahrenheit, now it's about 53 degrees Fahrenheit. That seems like a tiny uptick, but it has led to big changes: the summer of 2021 was the hottest ever recorded in Boston, and winter is about three weeks shorter than it used to be.

If we keep the globe to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the average yearly temperature in Boston will get to about 55 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050 and pretty much stay there.

If we keep doing what we're doing, emissions-wise, the temperature in Boston won't stabilize in 2050. Instead it'll hit about 60 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100.

"By 2050, no matter what, Boston is going to have a climate that feels more like Baltimore, Maryland," says Andrew Pershing, director of climate science with Climate Central. "By 2100, if we don't get the CO2 problem under control, Boston has a climate that feels like Raleigh, North Carolina."

Well that sounds pretty good — winters in Boston are brutal! Why is this a bad thing?

There are a couple reasons, says Pershing. First, Boston is not built to handle those hotter temperatures. And even if we could give everyone air conditioners, all that extra heat will lead to more flooding from sea level rise and heavier rainfall.

Take the Blue Line, for example, or the city's stormwater system — both a century old in parts and already getting overwhelmed with water.

The recent U.N. report on climate science also noted that global warming around 2 degrees Celsius will lead to many more "compound events," meaning a couple climate disasters in a row. Example: Hurricane Ida comes through New Orleans, knocks out power, then there's a heat wave and people die because there's no air conditioning.

"What if we got hit by two hurricanes in a row in the Northeast or two major nor'easters? Or, you know, a heat wave followed by a hurricane that knocked out power," says Pershing. "All of these things get so much harder once they start to stack on top of one another. And that's a big part of what the risk is in the second half of this century."

Also, at around 2 degrees Celsius of warming almost all the coral reefs die — not a Boston thing, but a major bummer.

OK, that doesn't sound great. But don't they have machines that can suck carbon dioxide out of the air?

Well, yes. But the existing carbon-suckers take so much energy to operate that they're not very practical yet. There's one in Iceland that runs off waste heat from a geothermal plant. That works in volcano-covered Iceland, but wouldn't work here in Massachusetts.

There are also carbon-sucking devices called "trees" but we keep cutting them down, so we should probably knock that off.

Eventually, the brainiacs will figure out direct-air carbon capture. But in order to get to 1.5 degrees Celsius and stay there, scientists tell us that we'll need to suck carbon out of the air and stop shooting greenhouse gases into the sky.

But what can Massachusetts do to stop emissions? We're just a state!

In order to keep the 1.5 degree Celsius target in reach, the world needs to get to "net-zero" emissions by 2050. Massachusetts is — of course — already ahead of the game, with that same target inscribed in state law.

Getting our state to net zero means, basically, that our forests, fields and wetlands must absorb more carbon than our cars, buildings and factories spit out. One of the hardest parts of that equation is our old buildings.

Almost 70% of the greenhouse gas emissions in Boston come from buildings. The city recently took a big step towards greening large buildings with a new ordinance called BERDO 2.0.

"The bigger challenge is making all those old brownstones and older buildings built before 1950 more energy efficient, which requires costly and time-consuming energy retrofits," says Cutler Cleveland, a professor of earth and environment at Boston University. He says lots of older, tough-to-retrofit buildings in Boston house low-income families, many of whom don't speak English, and many with vulnerable children and elderly people.

Advertisement

"Ultimately, we need new ways of financing those retrofits. Because, over the lifetime of a building, those retrofits have a very positive return on investment," Cleveland says. The problem is the upfront cost.

Well, at least our buildings run off natural gas, which is better than coal, right?

A recent study found that gas leaks in Boston are six times higher than state estimates. Those leaks undermine any climate benefit.

At the rate eastern Massachusetts is leaking natural gas, "the impact is equivalent to that of coal," says Maryann Sargent, a research scientist at Harvard who authored the recent study.

But guess what! One of the big topics at COP26 is how to stop methane leaks. And that's something everyone can agree on — you don't want gas leaks and the gas companies shouldn't want them, either.

Well that's hopeful. But still, climate change seems so overwhelming! What can I do?

Here's one easy assignment:

Have a look at WBUR's coverage of COP26. We have tons of stories covering the conference from different angles. Pick one, read or listen, and — here's the kicker — talk to someone about it.

A recent poll in Vice found that 60% of people "never or almost never hear about climate change from their friends and family." And as climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe said in her charming TED talk, talking about climate change, from the heart, is best way to fight it.

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a project aimed at strengthening the media’s focus on the climate crisis. WBUR is one of 400+ news organizations that have committed to a week of heightened coverage around the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow. Check out all our coverage here.