Advertisement

After leaving 'Mass. and Cass,' former Sox minor league pitcher has 'team' helping him toward recovery

One year has passed since Boston officials declared an encampment near Massachusetts Avenue and Melnea Cass Boulevard a public health crisis. At the time, more than 300 people were living on sidewalks, in tents and under makeshift shelters across about five city blocks. The streets were strewn with human waste, garbage and used hypodermic needles.

Mike Spinelli was one of the people living there. He spent about five years in the area, known as "Mass. and Cass," even through the depths of winter.

"There's been nights where it's, like, zero degrees," Spinelli said. "You're on a sidewalk with six blankets over you and three guys, like, huddling to keep warm."

But Spinelli isn’t living there anymore. He's one of more than 180 people who have entered permanent housing since the city began an effort to remove the encampment. The tents were dismantled in January, although some people continue to congregate in the area, and some returned to sleeping there by summer. As Spinelli and others have found, a move away from "Mass. and Cass" is just one step in the journey toward a more stable life.

A month after he moved into his own apartment, Spinelli showed off the one-bedroom in Boston's Fenway neighborhood to visitors. He called it "very cozy" and said he was enjoying the "beautiful view, with a beautiful breeze."

The apartment brought Spinelli a little closer — at least geographically — to a life he almost had in his grasp 25 years ago. He was on a path to pitching for the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park.

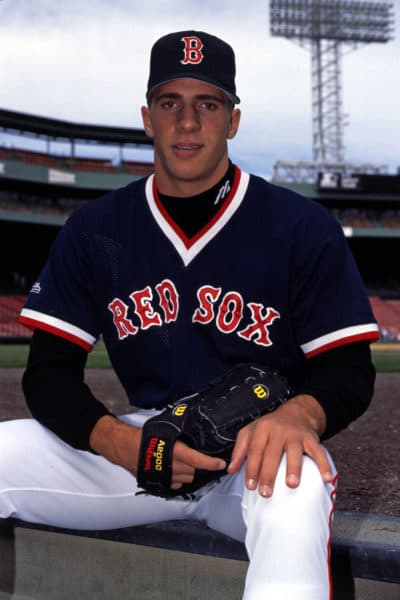

Spinelli had been a star pitcher at Revere High School — a southpaw known for his mean pick-off move. The Sox drafted him in 1995, and he played for their rookie and minor league teams in Florida.

But he was caught using steroids and eventually suspended. After he returned to pitching in 1999, he tore a ligament in his elbow and had to have surgery.

"They prescribed me Oxycontin. And I threw it away because I didn't like them. I didn't like the way they made me feel," Spinelli said. "And 13 months later, I tore it again, and I fell into a depression. And I took one [Oxycontin pill], and it made me feel unbelievable because it numbed me. So that's telling me that my psychological problems were taken care of by a pill."

And that's when he says his opioid addiction began. He used the opioid pills for five years and then switched to heroin.

A sense of security

Spinelli is now 46 years old. For the first time in a long time, he says he feels some sense of security. That’s because the place where he lies down to sleep at night is his.

"My first night here was awesome," Spinelli said of his apartment. "I slept on the mattress. When I woke up in the morning, it was, like, the best feeling, because I didn't have to worry about someone saying, 'You gotta go. You gotta do this, you gotta do that. You can't be here.’ I mean, that was the best feeling in the world."

The apartment has a donated couch, upholstered chair and other furnishings. Spinelli is grateful for them, but he can't wait to give the place his own touch. He envisions modern furniture, plants and candles. He wants to cook a big Italian Sunday dinner for his mother and brothers — homemade pasta with "gravy," as his Italian family says, not "sauce."

"So, yeah, I make gravy Sunday, and ... I cook everything. I can make cutlets. Like, anything that’s Italian, I can make," Spinelli said.

Advertisement

The 'team' behind him

Spinelli wouldn’t have come this far without help from Eliot Community Human Services. The nonprofit, which offers homeless and mental health services statewide, was tapped by the city to be the lead agency finding housing and providing support for people who lived unsheltered at "Mass. and Cass."

Eliot's outreach workers connect with people on the street to find out what care they need, then help them get apartments or enter transitional housing. The organization has helped 150 people from the tent encampment get into permanent housing over the past year.

Spinelli’s team from Eliot includes a case manager, housing director, certified addiction nurse and doctor. They connect him with services including mental health and other medical care, help him get to appointments and stop by his place or call to check in multiple times a week.

"Moving him in here, I mean, it was like tears and laughter, and it's just joyous."

Megan Sonderegger, RN

On the day we visited, much of his team stopped by, including nurse Megan Sonderegger, who specializes in caring for people with addiction. She's been working with Spinelli for about five years, but she wasn't aware of his stint as a ballplayer when she first met him.

"I didn't know who Mike Spinelli was because I don't do baseball. So it didn't impress me one bit," Sonderegger said, sparking laughter from Spinelli and other members of his care team.

According to Spinelli's case workers, when they first met him, he was using drugs so heavily that he’d struggle to carry on a conversation. He says he overdosed so many times he lost count. But the team from Eliot didn’t give up on him. They helped him get his birth certificate, Social Security card and an ID, so he could rent an apartment.

"We've been through a lot together, and it's just — it was a horror show," said Sonderegger. "So moving him in, I mean, it was like tears and laughter, and it's just joyous."

It took some time to get to move-in day. When the city cleared out the tent encampment, Spinelli first stayed at a public men's shelter. Then his team moved him to a temporary pop-up cottage at Shattuck Hospital in Jamaica Plain. The state worked with Commonwealth Care Alliance and Eliot to set up and operate the cottages as transitional housing for people moving out of "Mass. and Cass." Spinelli went from there to his apartment.

For now, his rent is paid with a housing voucher from the Boston Housing Authority. If he has income again, through work or Social Security, he'll be required to pay a portion of the rent.

Amid the joy and progress, Spinelli still struggles — a lot. Though he's not living at "Mass. and Cass," over the summer he said he was still going to the area for drugs.

He doesn’t have to be sober to keep his apartment. The outreach workers from Eliot and many other service providers work under what's known as a "housing first" model. That means they place people in permanent housing with support services, but they don't require clients to be in recovery to get and maintain that housing. The idea is that people can't even begin to rebuild their lives without a stable home. It's a key element of the strategy to help Spinelli and many others who were living at "Mass. and Cass."

But Spinelli wants to stop using opioids. By July, he and his support team were strategizing about treatment options. His care is complicated by the fact that he's diagnosed with severe depression and needs medical help for a serious injury. Last year, while in an opioid-induced "blackout," he says he walked off a loading dock near "Mass. and Cass" and broke a hip. His team has set him up with an orthopedic doctor. But he still walks with a pronounced limp and grimaces in pain.

"The only thing that does help is opiates," Spinelli said. "I don't get high to get high. I get high to get rid of the pain."

A radical step

Not long after we met him in July, Spinelli took a radical step toward recovery. He asked his team from Eliot to commit him to a treatment program under a section of state law that allows for involuntary commitments in certain cases when a person's addiction puts them in danger.

Spinelli’s housing case manager, Mark Bradshaw, said he's never seen a client ask to be committed, or "sectioned" as people sometimes refer to the process.

"It's definitely a bold choice and something that we don't take lightly doing," Bradshaw said. "He basically gave up all of his rights in that moment to make choices on his own. But I think he saw the opportunity that if he could have the time and space to prioritize his recovery, that's something that, you know, he could do."

Spinelli spent nearly two months at Taunton State Hospital. Two weeks after his discharge in September, we sat down with him in a park near his apartment. He said he was taking the medication Suboxone to treat his addiction.

"I've been clean for over two months now, and I feel fabulous. I feel amazing," he said, adding that the last time he had been clean for that long was probably 10 years ago. His children, 10-year-old twins and a 12-year-old, now want to visit with him.

"I set up dates to see my daughters," he said. "They've been asking for me."

The treatment program gave him lots of therapy and new tools to try to stay sober, Spinelli said. He takes part in support programs and meetings. He tries to stick to a daily routine that includes going to the gym.

He did go down to "Mass. and Cass" to see his friends after he returned home from treatment, but he said he realized it was a bad idea.

"I ask myself what I'm doing down there," Spinelli said. "I'm setting myself up, you know. So I stopped going down there altogether."

In his free time, Spinelli enjoys reading. He loves books by James Patterson and is currently reading "Big Bad Wolf." He also loves his Fenway apartment — which was waiting for him when he returned from treatment — and what it's doing for him.

"Without the apartment, I'm not getting clean," Spinelli said. "Because without an apartment, you know ... I'm depressed, or there's no structure, there's [nowhere] to keep your belongings. ... There's so much more, like, work being put into staying clean."

Even though his time and attention are focused on his recovery, Spinelli allows himself to dream. Despite knowing he won't make it to the pitcher's mound at Fenway Park in a Red Sox uniform, he wants to teach baseball to kids some day. He'd also like to give talks at schools to tell young people about his life and, hopefully, help them avoid what he's been through.

And when the stress of his addiction gets to be too much or he needs assistance, he turns to his care workers from Eliot for strength.

"I have great people around me. I have a great team," he said. "They are always there if I need them. And that is huge for me, because, you know, I always need help."

This segment aired on October 18, 2022.