Advertisement

Field Guide to Boston

The fascinating history of Boston's League of Women for Community Service

Resume

From the outside, 558 Massachusetts Ave. is an unassuming, fragile-looking brownstone. But the facade belies a fascinating interior that is steeped in Boston's Black history. And for the League of Women for Community Service, the brownstone has served, not just as the organization's headquarters since 1920, but also as an important and safe space for Boston's Black community.

Kalimah Redd Knight is the current president of the League of Women for Community Service. She's the latest in a long line of Black women stewarding the organization, which has prioritized community and educational services for Boston's marginalized communities. Though she's now president, Redd Knight didn't learn much about the League while growing up as a Boston student. "I had no idea that Black people were so prominent and did such amazing things in the city," she says. "I have family members who sort of went to dances at the League and things like that. But I didn't really know about the League."

It's a testament to how hidden some of Boston's Black history is, even within the city. Not only is the League one of Boston's oldest and longest-running Black women-led organizations, but it also provided an essential and pertinent safe space for the expression and preservation of Black culture. "I sometimes imagine what my experience would have been like had I known this information and had I had a space to go to where I could see myself," Redd Knight says.

From hosting dances and plays to providing room and board for women going to local colleges, the League was one of the few places in Boston that offered comprehensive services for people of color, especially Black women. Coretta Scott King stayed at the League for a year when she was attending the New England Conservatory of Music in the early 1950s. She was just one of many Black women who found a safe space within the League's walls.

"[The League] felt that it was important for them to provide resources," says Dr. Johnnie Hamilton-Mason, a Simmons University professor and researcher involved in the restoration of the League. "I think what stands out about this particular organization is that, up until like I think the '90s, they always had social workers. They always had educators. And a lot of their members were educators and some were nurses."

Education and literacy were major organizing principles of the League. They saw both as essential tools to uplift not just the individual, but the entire community.

The legacy of Maria Baldwin

Maria Baldwin was already an innovator when she became the first president of the League in 1919. She was an educator at the Agassiz School in Cambridge, where she eventually became its headmaster (the school has since been renamed to honor the memory and work of Baldwin).

This made Baldwin the first Black person to head an integrated school, "not only in Massachusetts but New England," says Redd Knight. "This was so rare because her entire staff was white and the vast majority of the students at her school were white. But she was this Black woman put in this position of authority, which is an incredible feat if you consider that this was really the top of the 19th century."

As a teacher, Baldwin opened up her Cambridge home to Black students attending Harvard University, one of whom was W.E.B. Du Bois (who Baldwin tutored). Beyond her work in the education field, she was closely connected and worked with Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin to found the Woman's Era Club, one of the oldest Black women's clubs, and The Woman's Era newspaper, one of the first newspapers in the United States to center and prioritize the experiences of Black women.

Baldwin was instrumental in securing 558 Massachusetts Ave. for the League's headquarters. "She actually purchased the property from the Farwell family," League board member Adrienne Benton says while giving a tour of the property. "And then when the League got incorporated in 1920, she quitclaimed it over to the League. So she was a very forward-thinking Black woman at the time."

The headquarters of the League

The building at 558 Massachusetts Ave. fell into disrepair in the 1990s but the vestiges of its former glory are still readily apparent in the interior of the house. It's a four-story Victorian-Gothic brownstone that was built in 1857 by William Carnes, a wealthy wood importer.

"This is the sort of penthouse," says Benton, as she stands in the fifth-floor billiards room. Almost every wall has windows and boasts a nearly 360-degree view of Boston. "And as you can see, back in the day, you could see all the way to Dorchester and also to Back Bay, because there were really no other properties around here."

When it was built, "it was considered the most opulent house in Boston," Redd Knight says. "And to this day, it probably is one of the very few spaces in the South End that continues to have all of its original fixtures." From silver doorknobs to mahogany and rosewood finishing, the property is the epitome of luxury. "The chandeliers are imported from Paris. I believe the wallpaper is from Brussels."

The house wasn't heated by fireplaces but by coal heat, which was a costly expense at the time. "There's also a lot of mirrors in the building," Benton says, pointing to the grandiose floor-to-ceiling glass. "When Carnes built the building, the mirrors cost something like $10,000 a piece in 1857."

A massive library, filled with important and rare texts, is also a feature of the house. When Maria Baldwin died in 1922, the library was dedicated to her. Many of the rare texts and letters have since been removed from the property and stored at Simmons University, where the League's archives are currently being processed. Among those documents is one of only three existing original copies of Ida B. Wells' "Southern Horrors: Lynch Laws in All Its Phases."

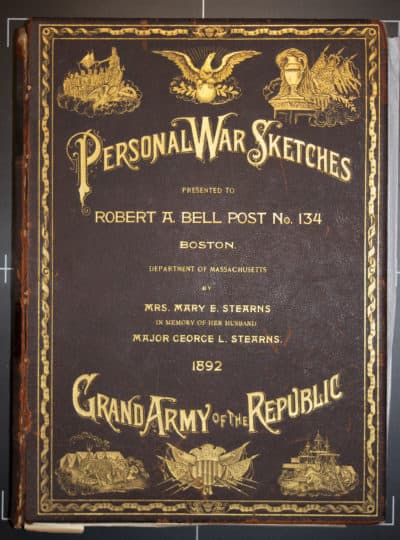

The League also recently launched a collaboration with the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library at Harvard to preserve and digitize the commemorative "Personal War Sketches" book found at the property. "It features members of the Robert A. Bell Post 134, Grand Army of the Republic, which was composed of the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Regiments and the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry — military units exclusively of Black soldiers," says Redd Knight. "This book contains first-hand accounts of Black soldiers who served in the civil war from these regiments. As far as we know, the stories have not been seen outside of the League for decades."

The letters and materials researchers and the League unearthed revealed how far the organization's connections extended. When Hamilton-Mason and League members went through the documents, they found that members and founders of the League had communicated with Booker T. Washington and Langston Hughes. "They had a deep network that extended beyond Boston and they used the Black press to publicize their events," Hamilton-Mason says. "They advocated for education in public schools early on."

Despite gentrification in Boston, the League has managed to keep ahold of 558 Massachusetts Ave. The League has gotten offers and calls to purchase the building but throughout the years, they've always made the decision to hold onto it. It's one of the most fascinating things about the property, that over 100 years since a Black woman purchased the building, the League "still owns it to this day," says Redd Knight.

A quest for restoration

A number of factors contributed to the building's repair needs. "The idea of a women's club, you know, was not in vogue after a period," says Redd Knight. "People found different ways to express their wish to advance civil rights than a traditional women's club."

While the League was a hotspot of activity for the Black community throughout the better part of the 20th century, things changed as Boston became more integrated. "The League really hosted events. And there was a period when Black people couldn't go to different hotels in the area," she says. "So when society opened up, the League sort of lost a lot of potential business opportunities to be able to gain revenue in different ways."

The demographics in the neighborhood changed as well, with urban renewal and gentrification contributing to the displacement of Black residents in the area. Women began to enter the workforce, "so they weren't able to contribute the time that they used to," Redd Knight points out.

The house is registered with Massachusetts' State Register of Historic Places, which has played another role in the slow restoration of the property. Certain elements of the house can't just be replaced — they have to be restored as close to their original state as possible or repaired with historic accuracy. This means the cost is higher than if the League was restoring a home without historical designation.

The League is running an ongoing capital campaign to raise the funds necessary to restore the building. "This restoration is going to be at least a $5-million project," says Adrienne Benton. "We've been able to raise $1.1 million through grants, but we still need to move towards securing the balance." Needed repairs include revamped electrical and plumbing systems, restoration of one-of-a-kind windows, repairing floor joists, plasterwork and much more.

The goal is to not only restore the property but to open it back up to Boston's marginalized communities. The point is to share the history of the League while crafting a future that aligns with why it was created in the first place.

"I think people don't realize how important it is to have a safe space where you feel acknowledged, where you feel cared for, where you are the center," says Redd Knight. "I think all of us feel so much pride when we come into the building. When we think about what our hope is for the future, [it's] to create a space for future generations to come, you know, to feel that measure of safety and acknowledgment."

This segment aired on February 24, 2023.