Advertisement

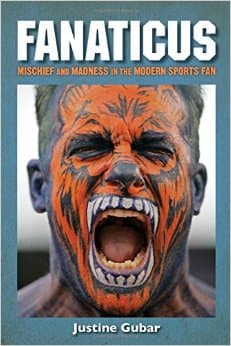

'Fanaticus' Explores Why Sports Fans Get Unruly

Fans. The word derives from “fanatics,” and some of them are. Enough of them so that Justine Gubar, an ESPN producer, decided to investigate the phenomenon of fans gone wild. The result is "Fanaticus: Mischief and Madness in the Modern Sports Fan.”

Gubar joined Bill Littlefield to share what she learned.

BL: You yourself had some unpleasant, even frightening experiences with fans. Let’s begin with a firsthand account or two regarding obnoxious fan behavior that you experienced up close.

JG: Well, as a producer for ESPN, I was spending some time back in 2011 in Columbus, Ohio. I was covering the Ohio State football program. Things were not going well. The football program was undergoing scandal. The head coach had just resigned. Fans were desperate and defensive.

JG: Well, as a producer for ESPN, I was spending some time back in 2011 in Columbus, Ohio. I was covering the Ohio State football program. Things were not going well. The football program was undergoing scandal. The head coach had just resigned. Fans were desperate and defensive.Any member of the national media was sort of considered the enemy. Someone had published my home number on the Internet, and I got pretty hateful voicemail messages that were so bad I actually had to call the police and file a police report. So all that hatred, I started wondering, "What's going on here?"

BL: You studied fandom in Europe and in Asia and in Latin America, as well as in the U.S. Can you generalize about fan behavior in one place or another?

JG: Well, it's hard, but the one thing I did come away with in "Fanaticus" is that there is a universality to bad behavior. I found evidence of inappropriate behavior at the most elite levels of sport and the lowest, most amateur, grassroots-level of sport. Sure it takes different forms in different countries, but it seems to be something within human nature and may hearken back to our hunter-gatherer origins, that we're tribal.

BL: In the chapter titled “The Age of Entitlement,” you explore the possibility that rowdy, even criminal, behavior by fans happens because those fans are charged prices they feel are too high for entertainment that doesn’t live up to its billing. Those fans feel like they’ve been ripped off — as if they’re victims. Did actual fans say that to you?

JG: Yes, you hear that sentiment from a lot of people. You go to a ballpark and people remember the price of their tickets.

BL: You conclude the chapter titled “And Then We Burn A Couch” with this contention: “It may be time for the sports world to acknowledge that just about anyone can turn into a rioter.” What led you to believe that?

JG: Well, it's interesting. Nobody really steps up and says, "Yeah, I wanted to burn that couch." There's a real sort of attitude of, "I was there. I'm not a bad guy or girl. I just sort of went along with the crowd." Now some of that may be excuses but if you talk to rioters, there's just a vague sense of a lack of control. Maybe you're not the guy who lights the fire in the dumpster but being surrounded by that energy and that stimulation — and maybe you have a few beers on you — it's not such a huge step to think that you may throw some newspaper on that fire.

BL: As you point out, “People have been trying to figure out how to control crowds for centuries.” Do you feel fan behavior in general is worse or more dangerous today than it was in ancient Rome, for example, or at Premiership soccer matches 40 years ago?

JG: That is a hard question to answer. The metrics in this area are sketchy. For example, if you're comparing arrest statistics at an NFL stadium from this year to five, 10 years ago, what are these numbers really showing you? Is it showing you that more people are misbehaving, less people are misbehaving, or that there's a zero-tolerance policy or that the laws have changed?

So it's hard to know, but what I have found is important is that it feels like it's getting worse. I hear fans who say it's not what it once was. And if the perception is there, if I have people coming up to me and telling me, "I don't want to take my kids to the game," then it's something that needs to be looked at and reacted to.

Bill's Thoughts On "Fanaticus"

In "Fanaticus," Justine Gubar draws some conclusions about fan violence, most of them unsurprising:

In some countries outside the U.S., “fan groups can embrace specific political leanings and ideologies.”

Some fans here feel “when you’ve paid money for a game…acting out is socially acceptable.” Some of those fans come to games already angry, since they feel they’ve paid too much for their tickets.

“Fandom touches on controversial issues far outside the sports world, for example, surveillance, privacy, free speech.” This “shows how deeply embedded fandom is in our basic identity.”

“It may be time for the sports world to acknowledge that just about anyone can turn into a rioter.”

Crowds where lots of people are wearing team colors are apparently more likely to riot than crowds made up of people who aren’t doing that, because when everybody’s wearing the team jersey, everybody feels anonymous and each individual is likely to believe he or she won’t get caught.

As far as rioting in particular and violent behavior by fans in general are concerned, alcohol is a dependable accelerant.

These conclusions seem to be consistent over time, or at least they might very well be, according to the author. Gubar writes that “if you are interested in a broad approach — different sports in different parts of the world — it’s impossible to know if fan violence is getting better or worse.”

The author supports these assertions with anecdotal evidence and comments from fans and professors.

More Featured Books On OAG:

This segment aired on July 4, 2015.