Advertisement

In Search Of Truth

Part I: The History Of How We Think About Truth

Resume

This series is produced in collaboration with The Conversation.

We kickoff our series on truth – how we use it, how we abuse it, what it means and what it’s worth to us.

Beth Daley, editor and general manager of The Conversation U.S. (@BethBDaley)

Joel Christensen, a professor of classical studies at Brandeis University. Author of "The Many-Minded Man: The Odyssey, Psychology and the Therapy of Epic." (@sentantiq)

Mustafa Akyol, senior fellow at the Cato Institute's Center for Global Liberty and Prosperity. Contributing opinion writer for the New York Times. (@AkyolinEnglish)

Interview Highlights

On the ancient Greek view of truth, and the poetry of Homer and Hesiod

Joel Christensen: “From the beginning, there's this connection between divinity and truth that has poetry as its mediator, which I think is critical. One of the things we often fail to understand about the ancient world is that poetry was the language of law and science, as well as what we might now called literature and religion. So if you went to the Oracle to get a prophecy, she would other the same meter as Homeric or hesiodic poetry, and they would record laws in the same way. And so there is not this sort of divide between poetry, creative arts and science — or logic and philosophy — that you would think of in the modern day.

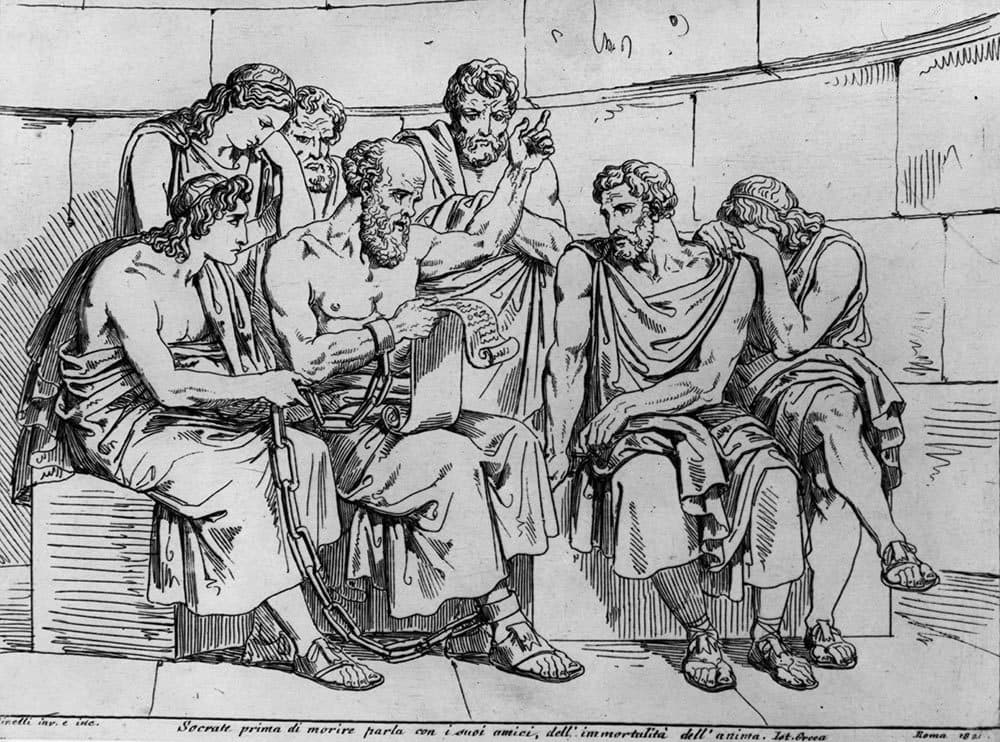

"And so to go back to the Hesiod bit. The reason it’s critical as an introduction is I think it's also about interpretation. It's saying we don't know what is true or what isn't. It's a positive statement of what I'd like to call epistemic humility, [saying] ‘We don't have the knowledge to judge whether or not a thing is true.’ And this comes up again later in the sort of Socratic dictum: that the wise man is the one who admits what he doesn't know. But when I teach how to interpret Greek poetry, what I focus on from this introduction is that it's telling us to make sense of the details as they exist, to listen to the story, to look at the whole before you make a judgment about what truth effecticity is. It’s saying, ‘Take truth aside for a moment because you don't have access to it. Instead, look at the story.’”

On the idea of truth as narrative

Joel Christensen: “I think the idea is that our consciousness and our brains depend on narrative connections and relationships of causality that exist prior to when we start to interpret a story. And so I think narrative is there, and how we structure facts in the world that makes sense. It's a basic sort of observation of psychological science that when confronted with facts that don't fit the world as we see it, we tend to ignore them. I think in Douglas Adams's books, ‘The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy,’ he called this somebody else's problem. And you just ignore it. It just goes somewhere else. … And there's a schism in philosophy based on this very issue, whether or not our perceptions can even get to external reality or truth. And whether or not that there is an external reality or truth separate from our perceptions. And this is the line between Stoics and Epicureans, and so the central issue Plato was concerned with in his early dialogues.”

Is there a particular individual in Islamic history that is important to study to better understand the notion of truth?

Mustafa Akyol: “First of all, I should say that for many Muslims, when you ask, ‘What is truth?’ both in history and today from the conservatives — at least today — you would get the answer, ‘Well, truth is established by revelation, period. God gave us scripture and that is truth.’ But when you ask, ‘OK, how do we know the scripture is correct in the first place? Well, why do we believe it in the first place?’ Then you get into discussions about justifying that and then reason comes to the fore. So the primacy of reason, at least, is acknowledged by some Muslims in history.

"And to come back to your question, I think the most interesting figure in Islamic history in that sense was, to me, the greatest philosopher in the history of Islam. It was Ibn Rushd, also known as Averroes in the West, who was a 12th century Cordoban philosopher who interpreted Aristotle from an Islamic point of view. And synthesized Greek thought, especially Aristotle, with his belief in Islam. And he had a great impact on European thought, as well. And I think he has some interesting insights about how [we] approach truth that are very relevant to some of our contemporary issues in the world today — about facts, alternative facts and so on, so forth.”

What would Ibn Rushd think about truth today?

Mustafa Akyol: “Ibn Rushd would be very disappointed today. He was disappointed in his time. And I should add that, I mean, despite his great ideas, his books in Arabic on philosophy were burnt in Cordoba, and he himself was banished and sent into exile because the conservatives of his time, you know, condemn him for 'heresy' quote-unquote. Luckily, he survived. But, you know, he was mostly wiped out from the Islamic memory. Interestingly, his books ... had more impact on Europe, rather than the Muslim world in itself. And that's an irony of history.

" … And of course, Ibn Rushd had this perspective, even that three-layered argument had some roots in the Greek philosophy. So it was a kind of elitist take of his time. But if he looked at today, he would ... again, see a lot of rhetorical argument out there. And let's not condemn rhetorical arguments. They are there. They're part of human nature. Sometimes rhetorical arguments can point [you] through, too. But they're not tested. So to be able to come to a conclusion — a fair-minded and objective conclusion on some point — you should not just give yourself to one rhetorical argument.

"And I think rhetorical arguments, typically what they do is, they rely on facts. I mean every argumentation-level here relies on facts, but they cherry-pick facts. I can find three things a year and make a conspiracy theory based on that. And, you know, and that conspiracy theory might appeal to the emotions of this social segment and society, and they might be motivated and valued by that. But we know that these things are misleading and also they lead to a lot of terrible things. I mean, that creates hate, that creates division.

"Especially rhetorical arguments are good when they make people good about themselves. I mean, they're successful and they can do that by boosting — ego-pumping — hatred and division. Whereas a demonstrative person should come out and say, ‘Wait, wait, wait. You're cherry-picking facts here. If you look at all the facts, it's not like that.’ So I think we are losing that fairness, level-headed, you know, serious expertise, which we shouldn't. And I think Ibn Rushd was warning about that in the world of Islam. He turned out to be quite right in his warnings at the time. And today, I think it's still an important warning.”

From The Reading List

The Conversation: "The ancient Greeks had alternative facts too – they were just more chill about it" — "In an age of deepfakes and alternative facts, it can be tricky getting at the truth. But persuading others – or even yourself – what is true is not a challenge unique to the modern era. Even the ancient Greeks had to confront different realities.

"Take the story of Oedipus. It is a narrative that most people think they know – Oedipus blinded himself after finding out he killed his father and married his mother, right?

"But the ancient Greeks actually left us many different versions of almost every ancient tale. Homer has Oedipus living on, eyes intact after his mother Jocasta’s death. Euripides, another Greek dramatist, has Oedipus continue living with his mother after the truth is revealed."

Cato Institute: "A New Secularism Is Appearing in Islam" — "For decades, social scientists studying Islam discussed whether this second biggest religion of the world would go through the major transformation that the biggest one, Christianity, went through: secularization. Would Islam also lose its hegemony over public life, to become a mere one among various voices, not the dominant one, in Muslim societies?

"Many Westerners gave a negative answer, thinking Islam is just too rigid and absolutist to secularize. Many Muslims also gave a negative answer, but proudly so: Our true faith would not go down the erroneous path of the godless West.

"The rise of Islamism, a highly politicized interpretation of Islam, since the 1970s only seemed to confirm the same view: that 'Islam is resistant to secularization,' as Shadi Hamid, a prominent thinker on religion and politics, observed in his 2016 book, Islamic Exceptionalism."

This program aired on February 24, 2020.