Advertisement

Rethinking how dyslexia is diagnosed

Resume

Dyslexia affects one in every 5 Americans.

But only 2 million are diagnosed and receive the help they need. Why?

Today, On Point: Rethinking how dyslexia is diagnosed.

Guests

Tim Odegard, professor of psychology and chairholder of the Murfree Chair of Excellence in Dyslexic Studies at Middle Tennessee State University. Host of the Dyslexia Uncovered podcast.

Clarice Jackson, founder of Black Literacy Matters. Founder of Voice Advocacy Center, a dyslexia screening and tutoring center. Founder of Decoding Dyslexia Nebraska, a nationwide parent support group created to raise awareness about dyslexia.

Transcript

Part I

This is On Point. I'm Meghna Chakrabarti. We're joined today by Tim Odegard. He's professor of psychology and chairholder of the Murphy Chair of Excellence in Dyslexic Studies at Middle Tennessee State University. He's also host of the podcast Dyslexia Uncovered. Professor Odegard, welcome to On Point.

TIM ODEGARD: Thanks. Thanks for having me.

CHAKRABARTI: I would love it if you could take us back into your own childhood as a start. When you were in second or third grade and you were in school, and you had sitting at your desk, with a book or an assignment in front of you, professor Odegard. Can you describe to us exactly you know what you saw as you tried to read?

ODEGARD: That's a great question. I saw a page full of words. Words that I knew that most of them, if I couldn't recognize them by sight from memorization, I probably wouldn't be able to read and pronounce. And I always worried in dread with this nauseous feeling that a teacher or a classmate or somebody would call on me and ask me to read those pages, read in front of them.

CHAKRABARTI: So when you say that it wasn't a word that you could recognize by sight, so if you saw the word school and you had already known, memorized what that whole word was you were okay.

ODEGARD: Correct. That's my compensation, is I've memorized and crammed a bunch of words that I've memorized over my life into my head.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. I don't mean to pry, but I think for many people who have, who do not have dyslexia or any kind of word processing challenges, it's hard to understand how when you see the word, for example, university, and it's not one that you had already memorized. For a lot of people, they would just look at the uni.

And be like, okay, uni-ver-sity, they would be able to work it out. But what did you see or what prevented you from being able to break it down like that?

ODEGARD: The child me.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. The child Tim.

ODEGARD: Wasn't clear on what was going on, why I was struggling to do it. What I would try to do is match it to a image in my head of a word that looked like that.

That I did know. And so I would call out and try to name a word that I might have known. So I might've said universe. If I knew that from a science class, that I had been able to memorize what the word universe was, I probably wouldn't have said university, but it would have been something like that. I might've even seen in a book and learned the word unicycle.

And I might've said unicycle. I didn't see the words backwards. I didn't see the letters backwards. It didn't jumble up for me. It was that it was difficult for me to sound them out as you were trying to do, to pronounce them from the letters and the sounds that went with them.

CHAKRABARTI: And tell me more about the dread that produced in young Tim.

ODEGARD: Two levels of dread. Typically, if you were given that seat work, it meant that you were supposed to be reading. Read on your own, and then you would have to go up and answer questions. There's a sense of dread that I would be found out and be thought of as not knowing what was in the book, because I couldn't access it.

I couldn't read it. So I would stumble through the words in my head. I would do better if I could have tried to have sounded them out laboriously, but of course the shame that I felt, and being in a room full of other people, I didn't want to out myself in front of them. So I wouldn't have been trying to read out loud.

At most, I might've tried to mumble under my breath. So the idea that I would have to go up and answer questions that a teacher had, or the whole class is now going to have to raise their hands and they're going to have to share what they read in the book. And of course, I would not be able to contribute, and I would be thought of as not knowing what my classmates knew.

CHAKRABARTI: I understand though that your memorization compensation, if I could call it that, and the effort that you put into it, actually worked really well for a while. There's an article where the reporter says that your teacher had moved you into the position of first reader.

ODEGARD: Yeah, that's exactly right.

So back when I was in school, it was very common for us to get these readers and we would have to read these books and we might do it in a small group of maybe five, six, seven, eight kids. And we'd be in a row and the person in the first year would read. And these are highly predictable so that the same words are going to repeat over and over again.

So by the time they got to me in the sixth, seventh, eighth position, I had seen all those words. I had used my, what we would call short term memory to memorize those, to be able to see them on the page and then call out what I had heard the other kids reading. So it looked as if I was very good at reading, and I kept getting bumped up, because I was so good and I wouldn't miss any of the words to being good at reading.

The fourth, the third, the second, and then the first. And of course, when I was in the first position, there was nobody else there to actually sound those words out for me, to read them for me, so I could memorize them. Of course, I was found out and then that resulted in me having to go and do some reading for the teachers.

They found out that I really wasn't able to read those words and I was no longer in that group. In fact, I found myself in a much different group with much different types of children than the ones that had been in there before. And reading the best I could.

CHAKRABARTI: Were you ever screened? When it became apparent later on that you were struggling?

ODEGARD: So I was doing all of this in the early '80s, and the concept of screening for literacy, which is so widespread and now part of legislation all over this country, as well as in Providences and Canada, was not possible.

Was not an option, did not exist. So the idea that I would have been screened in some kind of a screening format early in my grade would have not happened at that point. So I was tested, and they found me to not be able to read, to not be able to spell words, but as also reported in that article that you were referencing, I didn't qualify for any special services or protections under federal law, because of the identification model that I heard Sarah Carr in the top of the hour referring to the IQ discrepancy model.

CHAKRABARTI: So that's why we are so thrilled that you're on the show today. And I have a note here that says you prefer to go by Tim and not Professor Odegard, so I'll try to honor that. Because the question of how children are identified as having dyslexia and therefore eligible for supports is a really important one to this day. By the way, the article I'm referencing is from Scientific American. It was written by Sarah Carr. We have a link to that at onpointradio.org. But I do want to, so this evaluation, I don't know what to call it, test that you were given as a young boy.

Tell me a little bit more about that. What is actually tested, or was?

ODEGARD: It would have tested and would have been fairly rudimentary relative to what we have today, but still sufficient and still could have got the job done. It would have been having me read isolated words to see how well I could read different types of words.

So short words that are highly predictable, that you could use the letters and the sounds that go with them to read, probably a few short words that wouldn't quite fit those patterns. And then at that time, probably a few longer, more complex words that probably had more than one syllable in them. It's probably what they had me do.

They may or may not have had me do a spelling test. It was pretty apparent from my classroom performance that I couldn't spell, that was my weakest subject. For those of us in my community, those of us with dyslexia, that is often what we share in community, as being one of our largest struggles. So many of us are dismayed that we still call it a reading disability, for example, since we struggle to both read and spell words.

So we have aspects with multiple parts of written language, and they would have also probably given me, I know they gave me what would have been an IQ test at the time, that would have had a verbal component where I would have had to know what words meant. I would have had to have done other aspects to show that I understand spoken language and the meaning behind it. And I can understand it as well as express myself a little bit, and then they would have also had me do some, probably some what would have looked like visual games to me, maybe patterns with blocks, trying to build those out.

And they would have been determined if my full scale. So all that stuff coming together, was equivalent to likely higher than just 100 and high enough to get me a discrepancy of likely, at the time, about 15 points, one standard deviation between my reading achievement and my IQ. And because of the nature of that test and my background being from a blue-collar working-class background, didn't have college educated parents at home, definitely at that time they were biased against people from my community, my working-class background community.

CHAKRABARTI: In my mind, I'm hearing the sound of car brakes screeching to bring this conversation to a halt. Because you said that IQ was part of the evaluation, and this is the discrepancy model. This is what we're trying to learn about here. And is the discrepancy that, well, if a child's IQ is below a cutoff level or whatnot and they're a struggling reader, that to put it bluntly, this is what you quoted in the Scientific American article, that child is quote, too stupid to be dyslexic.

ODEGARD: Yeah, that would be one way of saying it. Yes. There's a lot of history and baggage that comes along with how this concept, especially in the United States, came to be. And a lot of language that we would deem pretty nonacceptable in today's way of thinking about the world wouldn't even be used, like mental retarded.

The term was educable, those who could be educated, versus those who were uneducable, mentally retarded children. So if my IQ had been higher, I would have been labeled as an educable, somebody who could learn, could be educated to do these things that I was struggling with. Mentally retarded individual, but I didn't have a high enough IQ.

So I guess that meant that I wasn't worth the trouble.

CHAKRABARTI: So the thinking, the historical thinking in this discrepancy model isn't so much that any child is having trouble or struggling as a reader, full stop, right? Which is what ideally it should be. It was, oh, they may be struggling as a reader, but we have to compare that to their measured IQ.

ODEGARD: Correct.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: Tim, before we get back to learning in detail, what this discrepancy model is, you will not be surprised to hear that when we told our listeners that we were going to be talking about this today, we got a real flood of responses. Because this is something that's having an impact in every state in the country.

So here's just a couple of listeners who shared their stories.

This is Xandra Sharpe in Greenbrier, Arkansas, and she said she ultimately had to move her son to a private school to get him the help he needed.

XANDRA SHARPE It was very frustrating because he was getting so much support at home to help him make better grades.

But because he wasn't failing, they would not test him. So I finally threw a fit. They finally tested him in eighth grade and they said, Oh yeah, he does have the markers of dyslexia and a processing disorder. And then COVID hit and we couldn't get further testing. So I ended up putting him in a private school that had a reading tutor and a dyslexia specialist.

And it was a game changer. I don't think that he would have gotten the support and resources he needed in a public school.

CHAKRABARTI: So that's Xandra from Greenbrier, Arkansas. And here's Alison Maree in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, telling us about her daughter.

ALISON: When she was tested, we were told that she wasn't behind enough so that she couldn't get on an IEP.

They needed her to fail more. I got an outside diagnosis and battled the system for almost a year before she got the intervention she needed. She graduates next weekend with an English degree from UMass Amherst. Without this intervention at that early age, I don't believe any of this would have been possible for her.

CHAKRABARTI: Just two of our many listeners, which we'll hear more from throughout this hour. So Tim, those are more modern stories, but they have echoes to what you were talking about. So let's go back to this discrepancy model that involved both reading ability and IQ. When was it created and why?

ODEGARD: I would say it was probably introduced in the late 1960s, early 1970s.

It was created because the illusions that you heard in those self-testimonials from listeners is really trying to find some kind of a processed efforts, some kind of a reason, causal mechanism why. We presume that it is neurobiological. It's born into how our brains are born and they develop. And that's what kind of the definition in our federal law, IDEA, the Individuals with Disabilities and Education Act codified. Was that it was something that was part of our psyche, part of our constitution. There is no genetic test. There is no brain test. There is no way of getting at that. As a result, when they were trying to codify and then implement this idea that was put into legislation, they had to come up with some model to do it.

So they're like if they had the potential, and so they were using this IQ as a marker of potential. Their overall potential is far greater than what we see them doing. And as a result, we could then invest in these children, knowing that they have the potential to learn, because they seem to have these isolated deficits, let's say in reading, maybe a little bit in writing, and they have these processing and advantages that we can see with this IQ test.

So we'll label them as special, as having these special needs and the special label of a specific learning disability. So it was really born out of necessity to try to operationalize something that was not theoretical, but was not something that we could put into practice. And we still can't today, despite all the efforts of all the brain imaging and all the genetic work that's happened around this.

CHAKRABARTI: Tim, I'm having a very hard time keeping my mouth shut, right? Because the idea that potential is the way to determine who's deserving of of intervention or support is shocking. Was there ever a time, whether it was in the development of the discrepancy model, or perhaps even soon thereafter, that people started thinking, hang on, maybe the fact that these children are struggling to read might actually have an impact in a lot of other things, including how they test in the so called IQ tests.

ODEGARD: So yeah, the early 1980s, Linda Siegel. Keith Stanovich, Jack Fletcher, Reid Lyon, and others started to publish research that was highlighting that the utility, the usefulness of the IQ test in differentiating between these people with greater potential versus what was then labeled a garden variety struggling breeder, just didn't meet any kind of criteria that would be used in any modern day classification and identification system.

So it wasn't passing what we would expect and hold in a medical model kind of a framework. It just wasn't passing muster. The other thing that was starting to emerge also was that we presumed in the United States when we were developing intelligence tests for lots of purposes, that this was the trait.

This was dispositional. This is how you were born. This is what you were going to do. And it would predict your ability and how high you could fly. But we've since learned that there are one, our biases, but more importantly, it changes over time. I know that you probably want to jump in here, but there's one really remarkable study that was published recently in a Northern European country, where they tracked individuals like myself who were identified and they had their IQ test when they were children.

Those who got the reading intervention, maintained that IQ 15 years later, but the kids who didn't get reading intervention had almost a full 15-point drop in their IQ on average. So if they had used a discrepancy model initially, as adults, they wouldn't have even met it, because IQ is not permanent. It is something malleable that changes.

CHAKRABARTI: But we're talking about this discrepancy model that's been around in some form for almost 50 years now. It has, as far as I understand, Tim, it's fallen out of favor a little bit, but are versions of it still in use in schools or elsewhere when people seek to get their children screened or tested?

ODEGARD: Yeah, most definitely. And I think that both of the cases that you heard with the callers who called in likely were forced because of the quality of education and the expectations. And how they were being handled in the schools wasn't meeting their needs. So they went to an outside tester who likely used a pattern of strengths and weaknesses.

So giving a, not a pure IQ test, but measuring very similar types of tests and then laying those out and looking to find patterns. And what they're looking for and what those callers were alluding to was finding these patterns where you could find these causal mechanisms or presumed causal mechanisms that were likely causing the reading problems.

ODEGARD: And as a result, they were able to come back to the schools, and then leverage those to get services. And the challenge we have is that as the IQ discrepancy has fallen out of favor, as the patterns of strength and weaknesses fall out of favor, the most important thing in our schools right now is quality education for all children. So that we actually can do our best and informing educators and refining how we screen to make sure that we're always able to dig down at the word level and we know to do it.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay, but to be clear about something, and it wasn't actually fully clear to me from the Scientific American article, is that even though we say this discrepancy model has fallen out of favor, the article says that thousands of schools in the U.S. continue to use an iteration of this model to test children.

Can you explain that?

ODEGARD: There's two aspects to that. So the federal legislation, IDEA, still has permissible three modes of identification. An IQ discrepancy is still allowable by federal law and can be adopted by any state or school in the nation if they chose to do, so it's still allowable. Second, the patterns of strength and weaknesses, giving a cognitive battery of tests and looking to see what the relative strengths and weaknesses are, to find a potential profile that would mark a child as having an SLD is now what a lot of schools are using in place of an IQ discrepancy, but it's still leveraging the exact same test and subtest, to large part as what an IQ does.

And now they're trying to get very complex and find these specific patterns that they think are linked to some type of a specific learning disability. The third is a instructional discrepancy. You're in a good school. They're using best practices. Most of the children are responding really well and are at grade level.

And when you're screening, they're reading lots of words, accurate. They're pretty fluent in what they do with them. They're spelling words well. There's just a handful that are left now that are struggling, and as a result of their persistent struggles, even when a little bit of intervention is used, you can identify them as needing much greater, more intensive, sustained intervention.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. In that case, how much has changed? The discrepancy model and its various iterations that you just laid out that are still in use. How much has that shaped, at the federal level? Or take it down as far as you want, state, local. Who's getting help?

ODEGARD: I think the sad thing is that I don't think the numbers have changed about who's getting help and who's not.

We've got some state laws in place now that actually require states to report how many kids and what percentage of kids are being identified with dyslexia. I've published several studies on this, and we're not seeing large swatches of children in Texas, Arkansas, such as that one caller from Greenbrier was reporting, or in Tennessee, for example, where I live currently, we're not seeing large swatches of children being mislabeled with dyslexia or even being labeled with dyslexia. At least when I published my first study on this, the most common number of children in a Texas high school that were identified with dyslexia was zero.

CHAKRABARTI: Zero, even though on average, 20% of the U.S. population has dyslexia.

ODEGARD: Zero. And it wasn't much different than that in Tennessee when I looked anecdotally at their publicly reported data. So you can see that we have this issue. In Arkansas, there's a steep drop off as well when you get to middle and then high school.

And that's what we observed across Arkansas middle schools, Arkansas and Tennessee, was that in middle school you see a steep drop off. It's perceived, and the stereotype is that it's a condition that we find early. That with good intervention and the foundational skills we remediate and that they're all fixed and better.

But I think as the one caller from Cape Cod was probably alluding to, if you're compensating, if you're working really hard as I did, as that caller's daughter probably is through your efforts, the harder we work, the less likely we are to get any federal protections, anything to support us in our unique needs.

And it creates what we commonly call a double bind. So you want to advocate against, let's say, an IQ discrepancy. I want to advocate against the cognitive model of doing this. But when we have schools that aren't well calibrated and aren't honoring the fact that if we struggle to read and spell words, it's on them to educate us.

And it's on them to find us and provide us with the supports and document the accommodations that we deserve.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. Again, let's go back to listen to some of the folks who shared their stories with us. This is Patty in Syracuse, New York. And she knew that her third-grade son struggles with reading.

She's known that since kindergarten, but getting the school's help was very challenging.

PATTY: They keep telling me that they don't test for dyslexia at the school level, yet when I talked to someone at the local university who could test him, she thought it was weird that the school psychologist couldn't test him because she, herself, is a school psychologist and can test him.

When I went to the school with that, they said, oh, yeah, now we can test him. We can test him. We'll just have to do it over the summer because we're short staffed. It feels with dyslexia, it's hard. You have to know the secret word, or the password, to be able to get what your child needs.

CHAKRABARTI: So that's Patty in Syracuse, New York, and here's Gina Nelson in Pelican Rapids, Minnesota.

GINA NELSON: It cost us several thousand dollars out of pocket to not only have our daughter diagnosed, but also to provide her the tutoring that she needed in her grade school years. Unfortunately, the schools do not have what they need to teach children with dyslexia, and it is very difficult on the children, and they end up growing up with a lot of anxiety because they are not understood, and they struggle in school.

CHAKRABARTI: I'd like to bring Clarice Jackson into the conversation now. She joins us from Omaha, Nebraska. She's founder of Black Literacy Matters, also founder of Voice Advocacy Center. It's a dyslexia screening and tutoring center. Clarice Jackson, welcome to On Point.

CLARICE JACKSON: Thank you. I'm happy to be here. Hello, everyone.

CHAKRABARTI: You heard Tim say earlier that the testing that he underwent as a young child in the early '80s was really tilted against helping someone from his background, working class, blue collar, not a lot of college education history in his family. So those class differences really have had an impact, as has race in terms of identifying students in need.

So can you talk a little bit about that? Like how has differential interventions or, excuse me, the discrepancy model, how has it had an impact on young Black children who were of whom who are struggling readers.

JACKSON: I would just first say that I think Tim and a lot of Black children or children of color have that same experience.

I know personally that my daughter who has dyslexia, she went through that very exact thing with the discrepancy model. That's what they were using here in Nebraska. And at that particular time, she had a psychologist of color. And because the psychologists of color understood the discrepancy model and the bias and the non-cultural diversity that can be used within that to work against children of color, she was very protective of the students that she attested.

And I kept wondering how my daughter was able to pass the test that said that she did not need assistance, but yet she couldn't read simple two and three letter words. And that's when I found out what the real issue was with the psychologist, but that IQ model is very problematic, for not only social classes, but also racial diversity as well.

CHAKRABARTI: Because IQ models of all sorts have been found to basically, in some cases, be overtly racist, in other cases be founded in the kinds of testing which would just intrinsically disadvantage some groups, including children of color, right?

JACKSON: Absolutely. Absolutely. I think that it lacks a lot of the language variations and the diversities that are included in them. And so it doesn't account for any of that. And that puts the child of color at a disadvantage, even though they may really truly be struggling from dyslexia. But that compounded bias that you find interwoven in the discrepancy model is not helpful in access and identification.

CHAKRABARTI: Can you so help me understand something a little bit more, Clarice. You had said that the psychologist who was working with your daughter was very protective of the children she was working with. That sounds like that's coming from a very good place though, right? I'm a little confused. Was her need, desire to protect those children not leading to the results that it should have?

JACKSON: I'm glad you caught that, but sorry.

CHAKRABARTI: It's okay.

JACKSON: I would say because at that particular time, my story is a little unique. So I happen to work at that particular school. So I knew the psychologist prior to her screening and testing my daughter. However, in her quest to think she was doing right by the kids of color, because she wanted, didn't want kids over identified. Because there's a disproportionate amount of African American students who are misidentified or over identified in special education.

So that was her lens. That was her baseline. And she had developed like personal relationships with these kids. And so she didn't want her to be labeled, but in the process of that, she was harming her.

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: So I want to learn from both of you about what are the better models out there that need to be used? And are they being used enough, Tim? How would you begin to answer that?

ODEGARD: I would actually say that the better models, if you were to say, is the instructional discrepancy, this response to instruction, is being used far more.

What we don't have is why Clarice struggled with her daughter, why a lot of your callers struggled, which is, that's supposed to be based on best practices and then having good intervention. And we don't really have those in the schools, which is why people from our communities have to go outside of the school in the first place.

And so we don't have the systems and the instructional knowledge and know how in place to run a better model. But when parents spend thousands of dollars to go outside of the school, then to come back, they find that they've got the diagnosis now, they've got the school agreeing, but their kids still aren't getting what they need.

So what this really says is that we need a ground up rebuild on how we're perceiving and working within our schools. At least that's my perspective.

CHAKRABARTI: So Clarice, actually I want to hear more about your daughter and then also the work that you're doing in Black Literacy Matters. Because this definitely seems like an issue that isn't going to be solved in one fell swoop at the federal level.

It's going to take a lot of the kind of work that you and Tim are doing. So tell us a little bit more about, about your daughter and how she's doing now.

JACKSON: Sure. Oh I'll start with how she started. And then she of course could not read in the fourth grade. She was still reading below a pre kindergarten level.

And she'd been in the traditional public school setting from pre-k to fourth grade. And again, we had that issue with the psychologist who didn't want her to be labeled or disproportionately placed in special education and therefore relegated to it and stuck. So we had to push past all of that, and they still could not objectively, scientifically, they didn't have a highly qualified teacher who even understood the science of reading to assist my daughter.

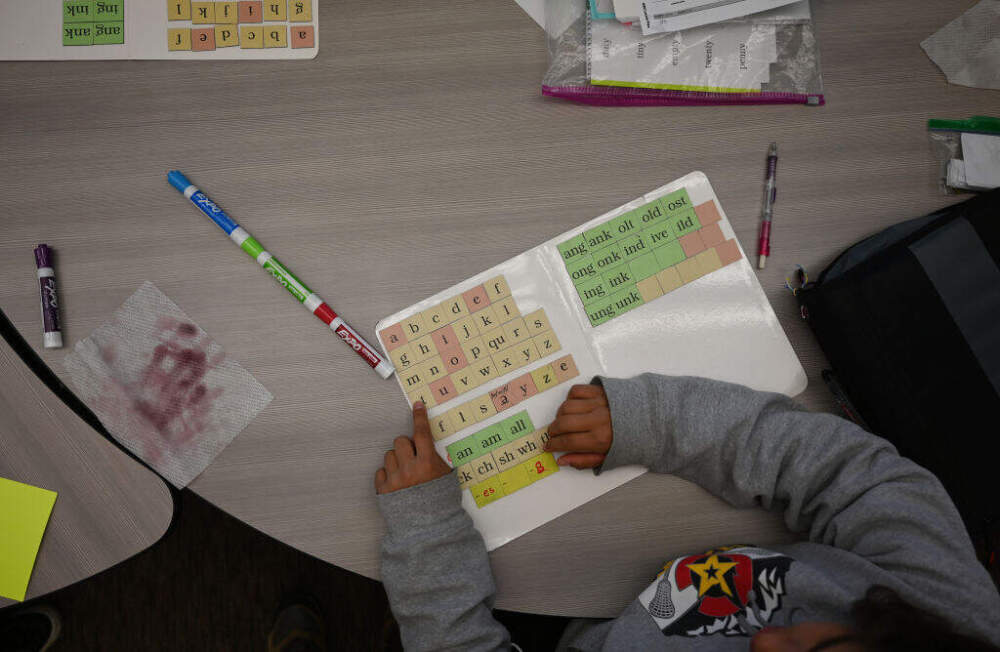

Like most of the callers, I had to look outside of the traditional school system, placed her in a private school where they used a Orton-Gillingham method, and in one year she went from a nonreader to a third-grade reader. And that was such a profound place for me after struggling and fighting and crying and homework at home that took hours, and she still didn't complete it.

And her belief in herself, I watched her belief in herself diminish. And I see that with tons of children who come through the doors of my center, or through parents or other advocates have expressed. That social and emotional impact, the educational trauma that children experience. Changes the trajectory of their lives if we do not catch it.

And that is so important to talk about, because you don't ever have to say a word to your child. If they know, which they do, that they're struggling or reading is not something they're good at, their belief in themselves diminishes, they withdraw within themselves. So you have very presumably introverted children who are truly extroverted, but are suppressing due to the fact that they have not been equipped with structured literacy practices.

CHAKRABARTI: This is so important, right? Because it does have an impact on absolutely every aspect of a child's life. I can completely understand what you say when they turn in on themselves, right? The idea of loving learning just diminishes. It affects them socially. With all of these truths, all of these truths being known, from your perspective, Clarice, what do you think is, what are the hurdles preventing schools from adopting different models or doing a better job at identifying the kids who need help?

JACKSON: After being in this work for a long time, and I think Tim could probably attest to this as well. A lot of it is schools pick curriculums.

Five to seven years out. And so once they pick these curriculums, by the way, a lot of these things are picked, like I know here where I am locally, they create curriculum groups, and we don't know what level of training or experience these groups that are picked have when it comes to choosing the particular types of books that will be placed in the classroom.

All that's decided above the level of the grassroots where the teacher and the child are and what's needed in the classroom. And so those things are decided. Then it becomes a political argument about, okay, if we do switch, how do we pay for it? How do we train a mass of teachers who've already been in the classroom from grade one, all the way up to 30 and 40 years, who don't have this type of training, and then it becomes that excuse.

And so while these things are arguing with each other, the lack of providing appropriate curriculum, not allowing curriculum like Lucy Calkins and Balanced Literacy, Pinnell and all of those different things. Into our school systems and let's have some knowledge about what we're choosing and does it have the evidence to back it to fully create literate children.

That's one of the huge issues and then for people of color it's then overcoming the barriers that are already there. I don't want my kid labeled as needing special services. I understand that there is bias in that. I also understand that our kids are not picked out to be gifted or talented or any of those things.

And I don't have the access. I don't have the reach, the bandwidth to work two, three jobs, then come up to the school and work in a PTA and be all things that the school says I need to be. And how about I come from the same system that failed my child, which has now put me in poverty. At the low-income level, to where I have to work all these jobs.

So now you want me to come home after working two to three jobs and read to my child and I can't even read. Those are some of the barriers that people of color face.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. You are singing my song, Clarice. (LAUGHS) If I could just put it that way, and I will restrain myself from diverting this conversation into the balanced literacy wars, because you mentioned Kalkins and F&P.

JACKSON: I'm sorry.

CHAKRABARTI: No, but that's part of the picture, right? Because these are decisions that districts have to make, right? It's the combination of identifying children who need help, but also talking about what schools are doing inside the classroom that may be making it harder for kids.

So I totally take your point on that. But Tim, so let me turn back to you here, because I just need a little bit more clarification. Because curriculum is a big part of this, but getting back to the evaluations, I just want to be sure I heard you correctly, that you said that a lot of schools are still using, if not of the old model, they're using evaluations that still look for patterns of strengths and weaknesses.

I think you've previously called it discrepancy 2.0.

ODEGARD: I did. Because I was being cheeky when I said that. So it's a way of thinking about it as being analogous in many ways, since very similar processing measures are used in this newer approach of patterns of strengths and weaknesses. So you're borrowing a lot and you're borrowing heavily from an IQ type assessment battery.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. So here's, let's get down to issues of dollars and cents, right? Because there just aren't unlimited funds for education anywhere, unfortunately, if you ask me. So ultimately there has to be some way to identify who is in need of help. Clarice, you had mentioned another evaluation system?

I didn't catch the name. It started with an O.

JACKSON: Oh, Orton-Gillingham? Yeah. Is that what you're talking about?

CHAKRABARTI: Is that another test?

JACKSON: That's not another test. That's just an approach or method that is used to teach children who are dyslexic how to read.

CHAKRABARTI: I see. Okay. Okay. So then thanks for that clarification because honestly in education, there's a lot of language that I have trouble keeping track of.

JACKSON: I'm so sorry.

CHAKRABARTI: No, it's quite all right. So Tim, what are the other ways that schools can somehow, I hate to say this, but identify who needs help and how schools can target the kind of support that those kids need. They need some kind of threshold, don't they?

ODEGARD: To build on one thing that you said, the dollars and cents, as well as the time, our treasure and then what Clarice said about the need for instruction and for the resources of dollars to do the work of actually teaching kids how to read in the first place, you could use an instructional model. Where we actually leverage and put money into the resources of teaching and equipping educators and giving students those resources to actually equip themselves with literacy.

That's what I would focus on. Research has looked at how much it cost. A midsize school district is anywhere from $500,000 to $750,000 are invested annually to do this type of testing that you keep referring to, across the nation. Now, a group then came back on that study that was published by a colleague of mine, Jeremy Miciak from University of Houston and said no. Actually it's closer to just a quarter of a million dollars. If you've got a handful of schools and you have a lot of the infrastructure you already need, which means you're already paying people.

You already have these very expensive tests, but they don't talk about the fact that these tests could take anywhere from eight to 10 hours of children's time away from an instruction. It's a lot of instruction and intervention a teacher could give to it, and you're taking resources of a paid position.

That could be a reading interventionist, it could be a person who is a coach and highly trained to support these people. By having and maintaining these models, we rob resources away from what we need for all of our students. Students who are low class like myself. From a poor background, students of colors, multilingual learners who are coming in.

Needing to be instructed and be identified with what they need and to build off their strengths. So we're robbing resources right now by maintaining this model, and we're putting the money into other people's hands.

CHAKRABARTI: Wait. So be clearer about that. So you're saying that there are already people in schools who, their work is in for different things, literacy coaches, things like that.

ODEGARD: They're there. But they're under resourced, they're under resourced. They don't have the resources to do it. When they need to adopt the new curriculum, when they need to pay for the sustained training, when they need to develop the in-house personnel to sustain full implementation of highly effective practices for all learners, and then have differentiated intervention to meet the needs of my child, of Clarice's child ... of other people's children. They don't have those resources. They don't have the capacity to do it, but they have the capacity to hire the people that they do for the testing. Because that's a compliance with the federal law. So they're doing a compliance mindset, which they have to do with the way the laws are structured.

And how they're held accountable.

CHAKRABARTI: I see. I see. Okay, so Clarice, this brings us back to the fact that, and I think it's reflected also in the callers who shared their stories with us and I'm grateful for all of them, but they're also coming from, a lot of the stories were for people who were able to go outside of the school system.

And find a way to get their child diagnosis and help, which means that they had the means to do it. Is that part of the problem that I've been reading, that that a lot of the more influential voices in the advocacy community come from that sort of white upper middle class group?

And that perhaps that's not the kind of advocacy that's reaching in districts that have a lot of children in need, but who can't advocate for themselves or families.

JACKSON: Absolutely. Absolutely. One thing is, and I know that there's some well-meaning people out here who quote this quite a bit, but if you come from a more prominent family, some might say, and I've heard it many times at many different conferences, that dyslexia is a gift.

And how do you tell someone who is in poverty, who is struggling, and we know, and we've heard that education is the gateway out of poverty, and you attend a school where access to appropriate reading intervention, structured literacy practices, are not there. And then your parents don't have the economic means to take you out of that school, put you in a private school or put you in a position where you have a tutor that tutors you 2 to 3 times a day.

And one of my good friends, Kareem Weaver says this, and I might be misquoting him a little bit, but basically, it's this. Is that you don't have a intervention problem. If more than half of your schools or your classrooms are struggling with literacy, you have an instructional problem. And so that is what has become the thing here in the United States, is that we are acting in the rears.

We are being reactive instead of proactive. And in the reaction, those that can't afford to find a different choice are stuck and relegated to these abysmal reading practices that we have, and thus we have the literacy gap between African American and their other racial counterparts.

CHAKRABARTI: We only have a minute left, and I really am mindful of all the families that are listening to this right now. Tim, what would you recommend that family members do if they have concerns about their children's reading.

ODEGARD: Advocate for themselves, try to reach out and get clear, concise information about what questions you need to ask, what information the school's collecting, look at those, have your child read to you.

Go in there and have your child read for their teachers. Hold the schools accountable for why a child like Clarice's daughter isn't able to read at even a kindergarten level. And you can clearly hear that if you take the time just to sit down and listen to her read. Use the misery that we feel as an opportunity for change.

This program aired on May 7, 2024.