Advertisement

Inside The Life Of Eisenhower's 'Mystery Man' — Smart, Efficient, Secretly Gay

You may not know the name Robert Cutler.

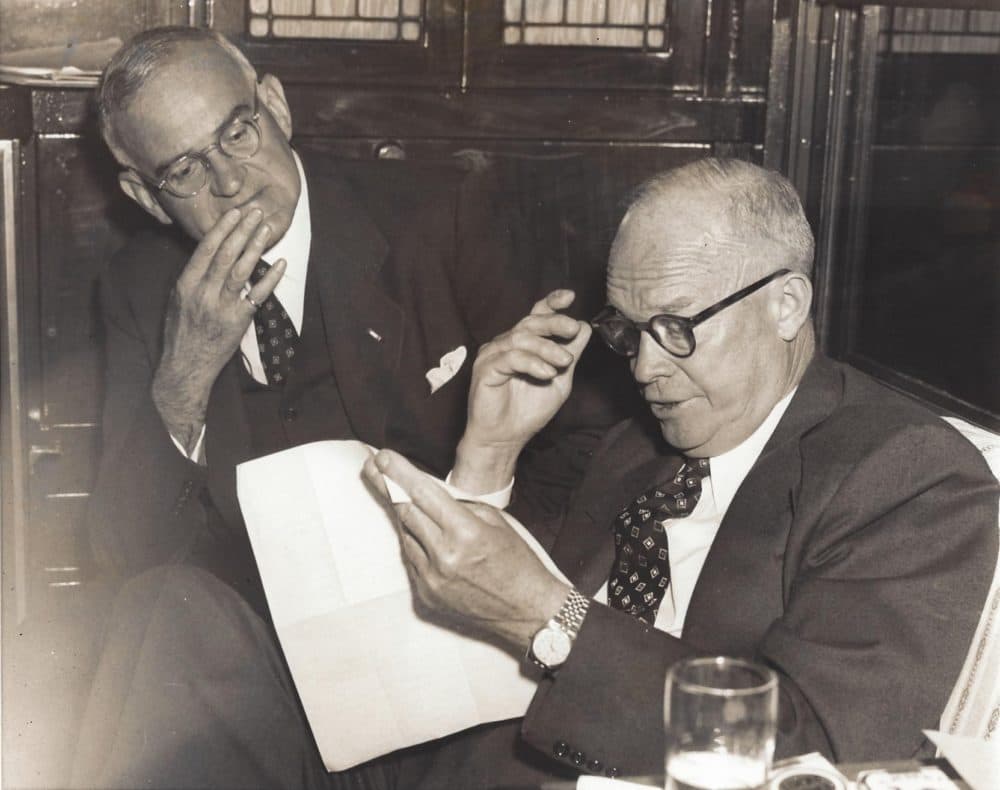

He was a charming Harvard raconteur, lawyer, former Army general and trusted backroom negotiator — so much so that President Dwight D. Eisenhower brought Cutler to Washington in the 1950s to overhaul national security, promptly appointing him the country's first national security adviser.

He was called "Ike's mystery man" — often at the president's elbow calling, for instance, for more candor about the dangers of nuclear weapons. No man with the possible exception of the president knew so many of the nation's strategic secrets, The New York Times wrote at the time.

He was also gay, at a time when being out meant losing one's career, or worse.

Cutler backed Eisenhower's efforts to ban communists, gays and lesbians from government, including Executive Order 10450. Those efforts came during the Red Scare — driven by fear of communists — and the lesser-known Lavender Scare, when Sen. Joseph McCarthy and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, both thought to be secretly gay, ferreted out others who were.

That led to not only disruption and persecution, but suicides.

"Executive Order 10450 identified and targeted a vulnerable minority, to point to this minority as causing lots of societal ills," reporter Peter Shinkle, Cutler's great-nephew, tells Here & Now. "It's an incredible example of what can happen: People who have political power begin blaming our problems on a minority."

Hoover would report his latest suspicions to Cutler, unaware that Cutler was gay. So were other men in national security: Skip Coons, a Naval intelligence officer who Cutler repressed while in government but fell deeply in love with later, and Coons' friend Stephen Benedict, who held several important security jobs after both Cutler and Coons died.

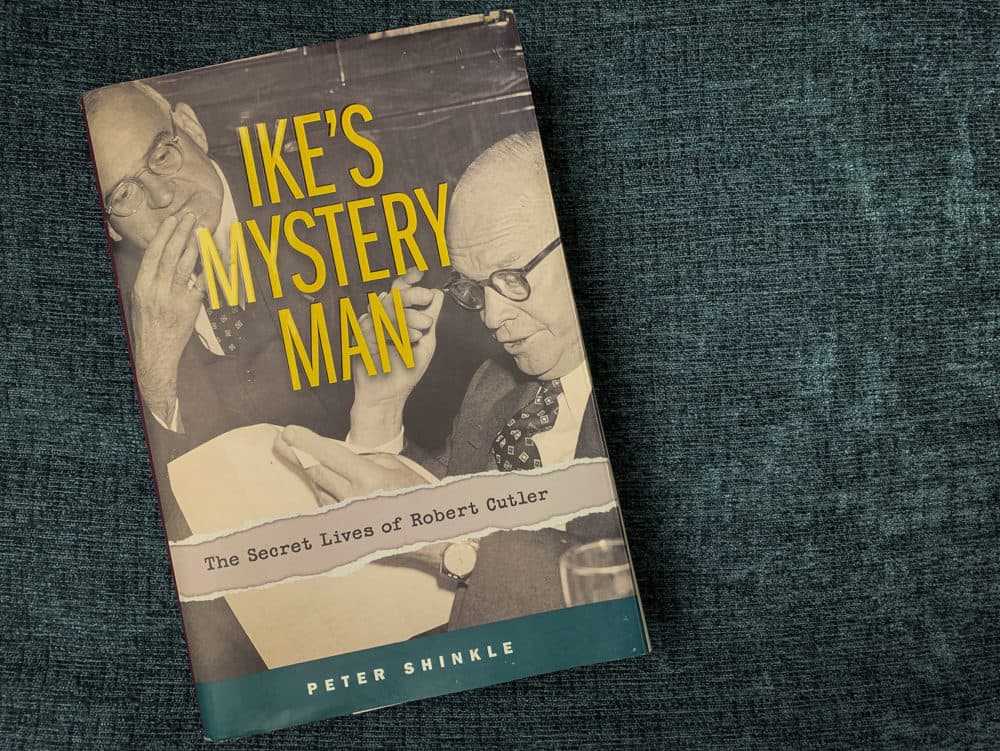

Benedict inherited Cutler's diaries, which he gave to Shinkle, who used them to write the book "Ike's Mystery Man: The Secret Lives of Robert Cutler."

"I lied many times, of course," Benedict, now 92 years old, recalls of working in government as a gay man alongside Cutler. "That was something one did almost like it came as natural as drinking a glass of water, because you knew that the atmosphere was such that you would never even be considered for a job were you to come out yourself."

Advertisement

Interview Highlights

On how the Lavender Scare originally came about

Stephen Benedict: "It really goes back to 1947, and that is when the Lavender Scare, so-called, really began to get a head of steam, and partly because it was associated with the whole Alger Hiss-Whittaker Chambers affair, which helped to combine these two issues of communism and homosexuality — it's almost complete myth. There's almost no truth whatsoever to the proposition that homosexuality predisposes anyone to either communism or to being blackmailed."

On Cutler gradually coming to terms with his sexuality

Peter Shinkle: "Bobby Cutler's life struggle to understand his sexual orientation played out through these very trying years in the crucible of the National Security Council. I think his final understanding that he loved this young man, Skip Koons, with all his heart came as late as 1957. It's actually all the sadder, because it is in many ways an unrequited love."

On researching and writing about Cutler's life

Shinkle: "The entire process was a 12-year journey for me, learning not only about my great-uncle's life, but also the experience of gay Americans. … Cutler did not have to bring forward [Executive Order 10450] that had been drafted under President Truman that contained the ban on sexual perversion. There had been another tightening of security rules that was proposed, and Cutler said, 'Mr. President, you should really go back and reconsider this other order.' And this is probably owing to Bobby's sense of procedural government. But the fact was that it was Bobby who went back and brought forward this order. My feeling is that Ike may well have understood that his top national security aide, Robert Cutler, was gay."

On Cutler choosing not to stand up and speak out against efforts targeting gays and lesbians in government

Shinkle: "I believe [it was a failure]. In all honesty — and I know Steve objected to this. In fact, what's fascinating about the debate over Executive Order 10450 is that there is virtually no record of anybody questioning the inclusion of the ban on sexual perversion."

Benedict: "I don't think that Bobby Cutler or anyone could have done anything to reverse a set of policies. It was inconceivable that in those days anyone could have suddenly taken a contrary position with respect to this whole issue."

On the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, which occurred roughly a decade after this period of persecution against gays and lesbians in the '50s

Benedict: "It was certainly a very important event. As far as I'm concerned looking back 70 years, the most extraordinary thing is how far we've come. Certainly not as far as we should. But in those days, to have conceived of gay marriage, for example, or someone running for the presidency who was openly gay and married, would have been utterly inconceivable."

More Photos

Book Excerpt: 'Ike's Mystery Man'

by Peter Shinkle

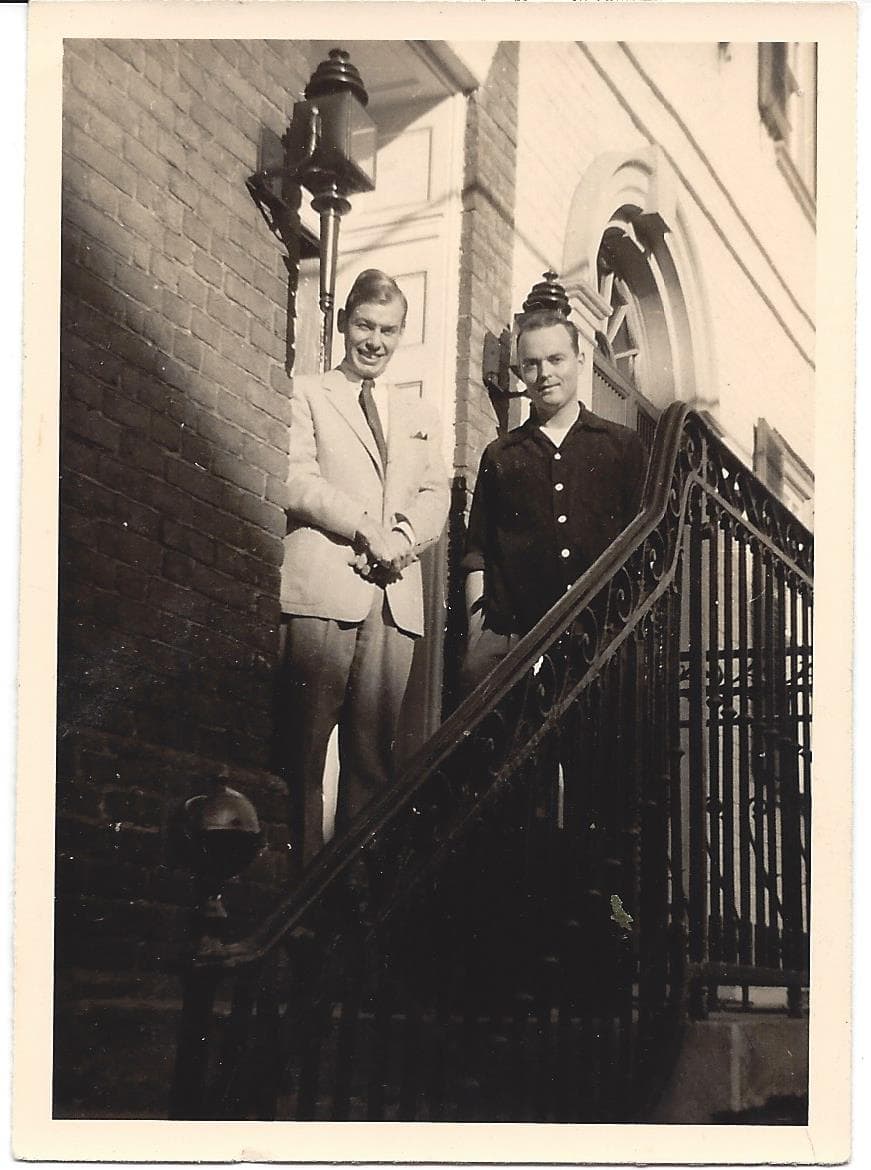

One day in late April 1954, Skip Koons and Steve Benedict drove to Alexandria, Virginia, a sleepy town on the Potomac River about eight miles south of Washington. Its leafy, brick-paved streets were lined with eighteenth-century colonial homes, some down-at-heel. The two young men toured a three-story rental property known as the Dr. Dick House, named after its former owner, Dr. Elisha C. Dick, a physician who cared for President Washington on his deathbed. The two young men decided that the elegant yet modest brick home located at 209 Prince Street, far from prying eyes in the capital, would be perfect for them. Skip and Steve needed to keep their homosexuality out of sight, and the Dr. Dick House soon became their refuge.

After Skip and Steve moved into the house in May, Bobby visited for cocktails on a number of occasions. His warm friendship with Steve had begun on the Eisenhower campaign train, and he had developed a close relationship with Skip working with him at the NSC on matters like Operation Solarium and the Guatemala coup. Skip had even introduced Bobby to his mother, Peggy Lutz, to whom Bobby had written in a letter in January 1954, “I have become very fond of Skip, and think he is a remarkably talented young man.”

Soon, Skip brought into the house a new boyfriend, twenty-three-year-old Gaylord Hoftiezer, who went by Gayl. A South Dakotan, Gayl had served in the US Marine Corps but was recently discharged. He soon began sleeping regularly in Skip’s room on the second floor, and Bobby became friends with Gayl, too.

Steve and Skip knew they needed to be discreet if they wanted to avoid trouble in McCarthy-era Washington, so they kept reasonable hours, didn’t have parties, and didn’t frequent gay bars. Their work life was routine, although their differing roles at the White House meant they had different schedules. Each morning, Skip and Steve would get in their separate cars — Skip, his black Thunderbird convertible, and Steve, his dark green Studebaker — and drive north along the Potomac, cross the bridge to Washington, and park in the White House parking lot.

Shortly after moving into the house, on May 24, Steve’s career took an astonishing turn when Eisenhower chief of staff Sherman Adams appointed him to be the White House security officer. His duties as security officer, to be performed in addition to his other duties as assistant staff secretary, chiefly entailed reviewing FBI background reports on potential appointees — like the ones on Bohlen and Vandenberg that had caused so much consternation — and report to Adams. A year had passed since Ike signed Executive Order 10450, which in effect had banned homosexuals from any federal job, let alone the position of White House security officer. Months after Steve took his new White House security post, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover invited him to a cocktail party at the Army and Navy Club in Washington for officials whose work brought them into contact with the FBI. Steve shook Hoover’s hand as they exchanged a polite greeting.

Excerpted from the book IKE'S MYSTERY MAN by Peter Shinkle. Copyright © 2018 by Peter Shinkle. Republished with permission of Penguin Random House.

Karyn Miller-Medzon produced this interview and edited it for broadcast with Robin Young and Kathleen McKenna. Jack Mitchell adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on June 26, 2019.