Advertisement

'Food For The Soul': Apollonia Poilâne Shares Secrets From Her Family's World-Renowned Bakery

Resume

Bread isn’t simply a mixture of yeast, water and flour.

Bread is “food for the mind, food for the soul,” baker Apollonia Poilâne says.

At only 18, Poilâne, daughter of the famed Parisian baker Lionel Poilâne, took over his world-renowned business. She made that decision within hours of learning of her parents' tragic death in a 2002 helicopter accident.

Now, after nearly two decades of running the family bakery, her pride in the craft remains rooted in her father’s “revelation” that bread connects people around the world, she says.

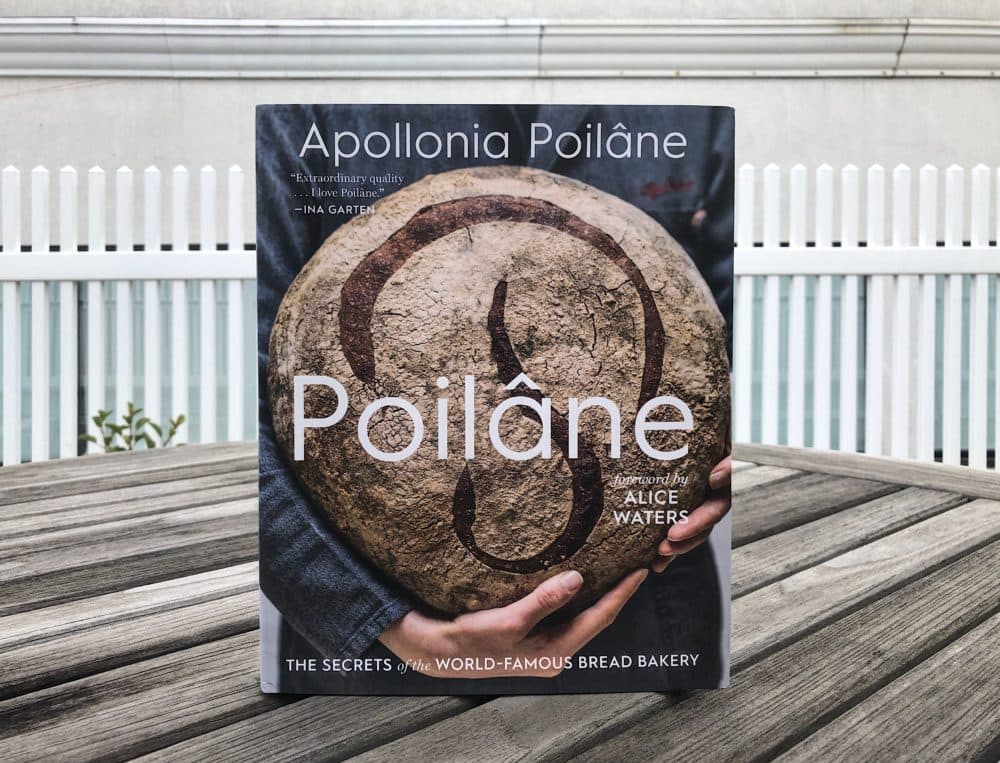

Continuing the family legacy, Poilâne’s published a new cookbook, filled with tips and recipes for the curious baker.

One flavor tip? Use French salt, if you can. She uses Sel de Guerande — a salt that comes from the Guerande region of France.

“It's very distinctive,” she says, “and it's definitely part of our signature.”

Investing in some of her tips, such as purchasing European butter with higher fat content or a 12-inch heavy-duty pot with a lid for sourdough, is about baking bread that meets standards passed down generations, she says, then getting to feel “the satisfaction of producing that handmade loaf.”

Interview Highlights

On her father and the art of baking bread

“So you have to imagine that on rue du Cherche-Midi there is a small brick-clad storefront, and in the basement, you have the bakehouse with a 100-ton heavy wood-fired brick oven. We bake that bread by hand, not because we want to do it the old fashioned way, but because that is where we have found our balance in baking.

“My grandfather started a recipe of this country-style loaf. And when you work at the bakery, our process has been perfected over the past 87 years. And my father had been forced by my grandfather to work in the business when he was 14. He was yanked out of school and that was it. And the revelation for him was that bread connects to the world. And whereas the popular thought in France was that a baker's job was literally something for people who were tall, strong and stupid. And he had a different outlook on this. He saw his craft as a link to the world because bread has fed generations before us. And that is what he shared with us from a very young age with my sister, and that has definitely fueled my passion for my craft and very naturally led me on taking over the family business.”

On whether the everyday baker can replicate her family’s world-famous bread

“I offer recipes so that people can reproduce the sensory experience of baking bread like we do at the bakery. … The limit of it is that when we bake one loaf or two loaves at the time, we don't have the same volume and we don't also have the same equipment that we do at the bakery. Unless you have that big oven that I was describing previously, you're not going to replicate the exact same environment.

“What my parents really mastered in building the manufactory is that at a time where they were expanding their distribution came a time where they were faced with this production dilemma. How do we scale without compromising on quality? And their response was we'll multiply the bakehouses. So at the manufacturer, there are 24 bakehouses, which effectively act as 24 small little independent bakeries one next to the other. And each baker works on his production from start to finish. So we can produce anywhere between on average 3,000 to 5,000 loaves a day because we increase the number of bakers and the amount of batches according to demand.”

On working in the bakehouse

“In many ways, when we're working in the bakehouse, we have the momentum and we have the volume to make our life so much easier than the home baker. And I think that was the hardest part of creating a recipe for this book because I've heard all too often people be discouraged by bread baking despite having a true passion.

“I remember my father would have me hand knead brioche every morning so that I can get a sense of what it is to hand knead a loaf. And it was a tremendous learning experience.”

On when Poilâne bakery opened in London, and her father had her light the ovens, a sort of passing of the torch

“You know, what's funny is that despite being very annoyed at being there and pausing for the picture, both my sister and I, we both felt however annoying it was, we knew that it would be something that in time we'd come to appreciate. And we did.”

On one of her father’s recipes, the bread sandwich, where the filling is bread

“Because it’s that filling and that sustaining! In the book, there are recipes of how to use bread as an ingredient, and that is beyond making bread or some of the Poilâne recipes. I wanted to show people that bread can also be a fantastic ingredient from crust to crumb. My recipes are intended to provide ideas to not toss away bread because when you know how much time it took to grow the grain, to mill it, to create the breads, I think you just can't just toss it away in the trash.

On whether you can tap on a load of bread, using your knuckles, to know if it’s fully baked

“Absolutely. And that is the best test to know. You can be misled by the color of the crust. The crust could be entirely burnt and the dough could be barely cooked inside.”

On continuing the family business

“Growing up, when people turn to my father to ask what I would do later on in life, he would really make an effort of not imposing on us that, so that it could be really be something that came from our hearts and our desire to take over the family business. And the first time I gave breath to a loaf, or when I see new generations of bakers or when I see clients whose children now come to the bakery, I feel a lot of pride in my family's tradition in that ongoing conversation between past and present.”

Recipes From 'Poilâne: The Secrets of the World-Famous Bread Bakery'

Rye Loaf with Currants

My father regularly ran home from the bakery before we went to school to drop off a small version of this loaf for our morning snack. He would cut it in half, add a generous pat of butter, and pack it for us to enjoy in his car. Today I still love to have a few slices—buttered or not—for breakfast or as a midmorning treat. We make this in metal loaf pans, but you can also shape it freeform.

Makes one 9-by-5-inch (23-by-13-cM) loaf.

Ingredients

- 1½ cups (240 g) dried currants

- 2½ cups (595 ml) hot water

- 230 g (1¼ cups) starter from Poilâne-Style Sourdough

- 435 g (3 cups plus 2 tablespoons) rye flour

- ¾ teaspoon (2 g) active dry yeast

- 1½ teaspoons (9 g) fine sea salt

- Neutral oil, such as canola or sunflower seed, for the pan

Instructions

- Put the currants in a medium bowl, add the hot water, and let soak for 10 minutes. Set a fine-mesh sieve over a bowl and drain the currants; reserve the soaking liquid.

- Pat the currants dry with a paper towel and reserve. Put the starter in a large bowl. Add the rye flour and yeast. In a small bowl, combine 1½ cups (355 ml) of the reserved soaking liquid (save the rest for brushing the loaf) and the salt, stir to dissolve the salt, and add to the flour mixture, along with the currants. With wet hands, mix and knead the dough in the bowl until it comes together in a smooth, homogeneous mass. Transfer the dough to a work surface and shape into a ball. Return it to the bowl and let rest for 15 minutes.

- Reshape the dough into a round, return to the bowl, cover with a cloth, and let rise for 1½ hours.

- Brush a 9-by-5-inch (23-by-13-cm)pan with oil. Turn the dough out and, using wet hands to prevent sticking, shape it into a 9-by-4-inch (23-by-10-cm) log. Transfer to the oiled pan. Brush a piece of plastic wrap with oil, drape it over the loaf, and let it rise in a warm (72°F to 77°F/22°C to 25°C), draft-free place until it rises about ½ inch (1.25 cm) above the sides of the pan, 1½ to 2 hours.

- Meanwhile, about 25 minutes before baking, position a rack in the lower third and preheat the oven to 450°F (230°C).

- Use a pastry brush to brush the top of the loaf with the reserved currant-soaking liquid. Bake until the loaf is golden and firm, 45 to 50 minutes; if you carefully remove it from the pan, it should feel hollow when you knock on it. Transfer the pan to a wire rack and let cool for 1 hour.

- Remove the loaf from the pan, return to the rack, and let cool completely before slicing. Stored in a paper bag or wrapped in linen at room temperature, the loaf will keep for up to 1 week.

NOTE: As with our sourdough, you will either need to have the starter on hand or plan ahead to make it, which takes a couple of days.

Bread Crumbs Tabbouleh

Peek into a Parisian’s picnic basket and you may just find tabbouleh, the bulgur salad featuring loads of chopped parsley and tomatoes, seasoned with olive oil, lemon juice, salt, and pepper. In France, we tend to make the dish with more grain than the classic version, which is all about the parsley. I make mine with toasted bread crumbs, which have a texture similar to bulgur. This tabbouleh retains the fresh, vibrant feel of the original, and the tang of the sourdough crumbs balances the sweetness of the ripe tomatoes.

Serves 4 to 6.

Ingredients

- 2 tablespoons (30 ml) extra-virgin olive oil

- 2 cups (130 g) finely ground bread crumbs (see page 181), preferably from Poilâne-Style Sourdough (page 50)

- 4 ripe medium tomatoes, diced 1 medium white onion, finely diced (optional)

- 4 loosely packed cups (120 g) coarsely chopped fresh flat-leaf parsley

- ½ cup (15 g) coarsely chopped fresh mint

- Juice of 2 lemons

Instructions

- Heat the olive oil in a large skillet over medium heat. Add the bread crumbs and cook, stirring occasionally, until golden and crisp, 5 to 8 minutes. Transfer to a large serving bowl and set aside to cool.

- Add the tomatoes, onion, if using, parsley, mint, and lemon juice to the bowl and mix to combine. Cover the bowl with plastic wrap and refrigerate for at least 2 hours, and up to 6 hours, before serving.

- Serve the tabbouleh chilled.

Excerpted from POILÂNE: The Secrets of the World-Famous Bread Bakery © 2019 by Apollonia Poilâne. Photography © 2019 by Philippe Vaurès Santamaria. Reproduced by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.

Karyn Miller-Medzon produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Todd Mundt. Serena McMahon adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on November 5, 2019.