Advertisement

The Day America Went Dry: Looking Back At Prohibition 100 Years Later

Resume

The United States began its “noble experiment” 100 years ago when the 18th Amendment to the Constitution banned the production and sale of alcohol.

For a relatively brief 13 years, Prohibition was the law of the land, and it changed the culture of the U.S. for generations to come.

But why did the U.S. ban alcohol in the first place?

“The biggest problem was that ever since the founding of the colonies, Americans were heavy drinking people,” says William Rorabaugh, professor of history at the University of Washington and author of “Prohibition: A Very Short Introduction.”

Back then, Americans drank mostly cheap whiskey produced from corn grown in the Midwest, he says. And all of this drinking led to bad behavior.

“There was a lot of whiskey drinking and a lot of public drunkenness, child abuse and wife beating and crime and poverty,” Rorabaugh says. “And after the Civil War, there were a lot of Civil War veterans who were self-medicating with alcohol.”

In the 1890s, the Anti-Saloon League successfully lobbied to ban alcohol at the local, state and then finally the federal level. As a result, “drinking went underground,” Rorabaugh says. Saloons and restaurants that served alcohol were forced to shut their doors.

“And instead, speakeasies opened in basements in places where they didn't have signs on the door. Sometimes they were in apartment buildings,” he says. “And they wanted to rent — cheap rent — so a lot of the speakeasies were located in low rent neighborhoods.”

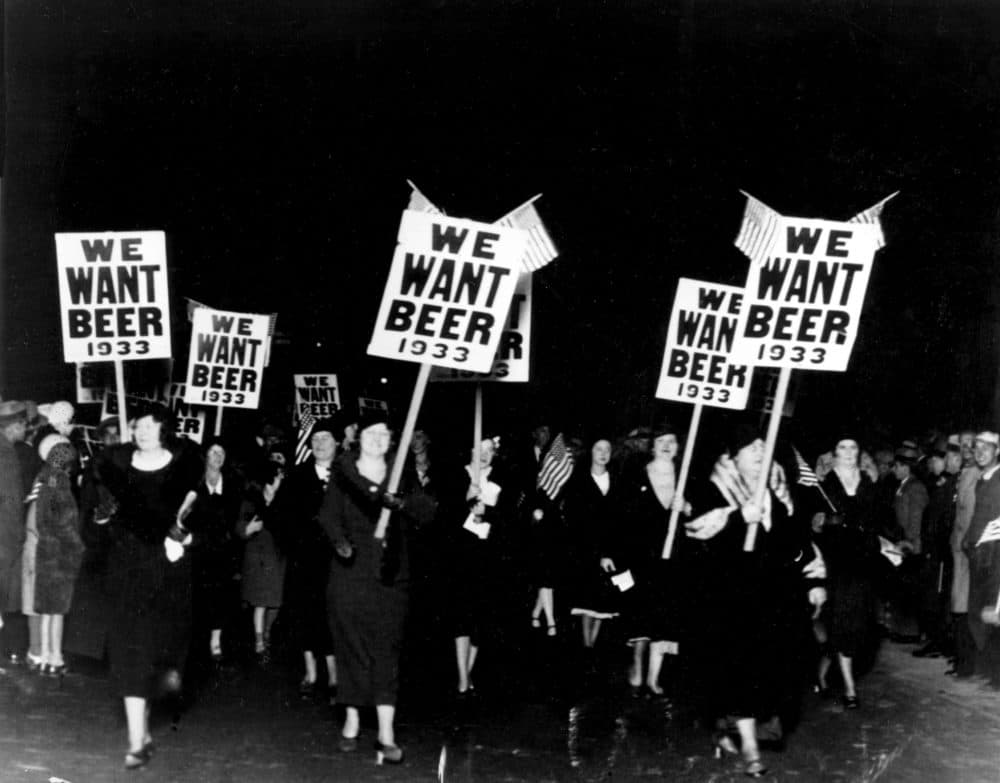

Even though it was against the law, many people didn’t stop drinking, Rorabaugh says. And in 1933, the 21st Amendment was ratified, effectively ending Prohibition.

“I think it's fair to say that it was folly. It didn't fit the fact that alcohol had been a traditional drink with Americans going back to actually the Mayflower,” he says. “And so there just wasn't any way that a hard-drinking society could ... turn the spigot totally off.”

Interview Highlights

On why the alcohol lobby wasn’t able to stop Prohibition

“Well, the only place where there was wine was California. The California wine industry did have influence in California, but not outside the state. The distillers had discredited themselves. They were caught in a scandal in the [Ulysses S.] Grant administration bribing federal inspectors not to pay taxes. So no one wanted to have anything to do with the distillers or the distillers were kind of out of it politically. The political power came from the brewers, and Americans switched after the Civil War from whiskey to beer. And almost all the breweries in America were German or German immigrants or the children of Germany.

“If you're trying to stop Prohibition, the people who really wanted to stop this are the brewers and the saloon keepers. And so they have to funnel money into the politicians that will try to stop this. But they can't give money openly because that's too, you know, that doesn't look good. So they give money through something called the German American Alliance, which was founded in 1900 by the Kaiser as an official organization of German immigrants in the United States to promote friendship between Germany and America. And so in 1914, when World War I breaks out, the German American alliance is pro-German in all of its propaganda. They're pro-German in the war, but they're also pro-alcohol.”

On the impact of Prohibition on people’s drinking habits

“A large number of people did stop drinking and maybe more accurately, a large number of people never started drinking because think about it: If you were born in 1900, the first time that you could take a legal drink would be 1933. And by the time you were 33 years old, perhaps you didn't care anymore. The heaviest drinking period in people's lives is in their 20s. So … they became a light drinking generation. But of course, the speakeasies also became places where people did drink and particularly in big cities like New York and San Francisco and Chicago.”

On why the 21st Amendment, which ended Prohibition, was ratified so quickly

“Public opinion turned. It started to turn in the mid-20s. But I think what really did it was the rise of criminal gangs that were major gangs. One thinks of Al Capone … in Chicago. The TV series Boardwalk Empire about Atlantic City is actually based on a real story. And Atlantic City was one of the major places of corruption.”

“You no longer had tax revenue coming in from alcohol. Instead, you had to raise taxes of other types, particularly the income tax. And in addition to that, the bootleggers were getting rich. The price of alcohol did go up. During Prohibition, alcohol cost about five times as much as it did before Prohibition. And of course, all that profit is going right into the pockets of Capone and people like that. And they don't pay any taxes on that money either. … It was also a kind of naivete on the part of people who said, 'Oh, if we just pass a law, that will be the end of it. People will stop drinking.' And they didn't grasp that people who liked to drink were not going to stop drinking just because it was a law.”

On Prohibition’s lasting impact on the U.S.

“Well, one of the things that [Franklin D. Roosevelt] was very clear about in 1933 was that he wanted legal alcohol, but he also wanted alcohol taxed and he wanted alcohol regulated. As a result, alcohol, which had been almost a wild west drink before Prohibition — there were very few rules of any kind — and so Roosevelt wanted to make sure that we didn't go back to a system where you just sold anything to anybody anytime. And instead, you had a more regulated kind of environment with taxes that were actually necessary. And one of the major reasons that repeal took place in 1933 was that every government in the United States — city, county, state and federal — was hurting for money. Meanwhile, there's Al Capone making $200 million a year untaxed.”

Francesca Paris produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Kathleen McKenna. Samantha Raphelson adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on February 7, 2020.